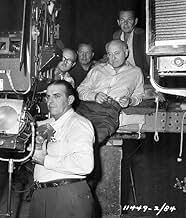

George Barnes(1892-1953)

- Cinematographer

- Camera and Electrical Department

Veteran cinematographer George S. Barnes had a well-earned reputation

for reliability and a knack for combining artistry with economic

efficiency. As a result, he was seldom out of work.

Having started as a still photographer for Thomas H. Ince in 1918, Barnes quickly rose through the ranks to director of photography. In the course of his career he spent time at just about every major studio in Hollywood: Paramount (1919-21), Metro (1924-25), United Artists (1926-31), MGM (1932), Warner Brothers (1933-38), 20th Century-Fox (1940-41), Universal (1942) and RKO (1942-48). During the 1920s he was the primary cinematographer for Samuel Goldwyn and was largely responsible for the success of films like L'ange des ténèbres (1925). Under his auspices Gregg Toland learned his craft, particularly Barnes' trademark soft-edged, deep-focus photography and intuitive composition and camera movement. Barnes was an expert at lighting. He often utilized curtains or reflective surfaces to create patterns of light and shade. Most importantly, he perfectly suited the required style of photography to each individual assignment. He brought a vivid opulence to the dullish Technicolor romance L'aventure vient de la mer (1944), making it a triumph of style over content. His 'catoon colors' were just as perfectly suited to the fantasy adventure Sindbad le marin (1947). At Warner Brothers the dark, somewhat grainy texture of films like Femmes marquées (1937) was in sync with the realistic look the studio wanted to achieve for its product. He also excelled at shooting vivid dramatic scenes, such as the flood sequences featured in La conquête de Barbara Worth (1926).

Barnes did his best work in the 1940s, shooting two classic Alfred Hitchcock thrillers: for Rebecca (1940) he created an atmosphere of sinister foreboding, right from the beginning, with his shots of Manderley (Barnes was hired because Toland was unavailable, but he ended up winning an Academy Award); and La maison du docteur Edwardes (1945), with its unsettling surrealist Salvador Dalí-designed dream sequence of wheels, eyes and staircases. A lesser, but nonetheless good-looking, addition to Barnes' resume is a minor film noir, La femme à l'écharpe pailletée (1949). In contrast, he created a suitably lavish look for his color photography, which enlivened two charismatic swashbuckling adventures, Pavillon noir (1945) and Sindbad le marin (1947). Popular with directors and producers (though he was once fired by David O. Selznick for failing to bring the best out of Jennifer Jones) and stars (Bing Crosby) alike, Barnes was continually employed until his death in 1953. He was also popular with the ladies, to which his seven marriages testify. One of his wives was the actress Joan Blondell.

Having started as a still photographer for Thomas H. Ince in 1918, Barnes quickly rose through the ranks to director of photography. In the course of his career he spent time at just about every major studio in Hollywood: Paramount (1919-21), Metro (1924-25), United Artists (1926-31), MGM (1932), Warner Brothers (1933-38), 20th Century-Fox (1940-41), Universal (1942) and RKO (1942-48). During the 1920s he was the primary cinematographer for Samuel Goldwyn and was largely responsible for the success of films like L'ange des ténèbres (1925). Under his auspices Gregg Toland learned his craft, particularly Barnes' trademark soft-edged, deep-focus photography and intuitive composition and camera movement. Barnes was an expert at lighting. He often utilized curtains or reflective surfaces to create patterns of light and shade. Most importantly, he perfectly suited the required style of photography to each individual assignment. He brought a vivid opulence to the dullish Technicolor romance L'aventure vient de la mer (1944), making it a triumph of style over content. His 'catoon colors' were just as perfectly suited to the fantasy adventure Sindbad le marin (1947). At Warner Brothers the dark, somewhat grainy texture of films like Femmes marquées (1937) was in sync with the realistic look the studio wanted to achieve for its product. He also excelled at shooting vivid dramatic scenes, such as the flood sequences featured in La conquête de Barbara Worth (1926).

Barnes did his best work in the 1940s, shooting two classic Alfred Hitchcock thrillers: for Rebecca (1940) he created an atmosphere of sinister foreboding, right from the beginning, with his shots of Manderley (Barnes was hired because Toland was unavailable, but he ended up winning an Academy Award); and La maison du docteur Edwardes (1945), with its unsettling surrealist Salvador Dalí-designed dream sequence of wheels, eyes and staircases. A lesser, but nonetheless good-looking, addition to Barnes' resume is a minor film noir, La femme à l'écharpe pailletée (1949). In contrast, he created a suitably lavish look for his color photography, which enlivened two charismatic swashbuckling adventures, Pavillon noir (1945) and Sindbad le marin (1947). Popular with directors and producers (though he was once fired by David O. Selznick for failing to bring the best out of Jennifer Jones) and stars (Bing Crosby) alike, Barnes was continually employed until his death in 1953. He was also popular with the ladies, to which his seven marriages testify. One of his wives was the actress Joan Blondell.