VALUTAZIONE IMDb

7,7/10

9597

LA TUA VALUTAZIONE

Le interviste di Varda spigolano in Francia in tutte le forme, da quelli che raccolgono i campi dopo il raccolto a quelli che setacciano i cassonetti di Parigi.Le interviste di Varda spigolano in Francia in tutte le forme, da quelli che raccolgono i campi dopo il raccolto a quelli che setacciano i cassonetti di Parigi.Le interviste di Varda spigolano in Francia in tutte le forme, da quelli che raccolgono i campi dopo il raccolto a quelli che setacciano i cassonetti di Parigi.

- Regia

- Sceneggiatura

- Star

- Premi

- 16 vittorie e 3 candidature totali

Recensioni in evidenza

This is Varda going out again with just a camera. This time she finds vagrants and gatherers of all kinds around the streets of France, some who pick up after discarded harvests in the fields, others who find their objects of art or utility in what people abandon in the street corner.

There's a French history of "gleaning" that she references via paintings of women picking up wheat in the fields, that is of course her entry into images of life she gleans with her camera, herself a gatherer, but in another way it is to situate what we see as a certain rite of life with its continuity, something that people do.

So I like that we're called to see beyond desperation here, though at a glance many of these lives will seem dismal. Varda has taken an interest in itinerant lives for a long time as previous films by her suggest, Vagabond most notably, and she has the sensitivity of empathizing. We do see a few troubled individuals, because life kind of swung that way before they had a chance to hold on perhaps. But we also see a life that manages just fine for itself and roots itself in the other, something like the anti-ego philosophy of one of the people in the film.

None of them are vexed to live as they do, that we see anyway, and it manages to remind me of the ancient Taoist injunctions to forego the anxieties for "humanity" and "responsibility", often hypocritical, and make yourself like a clump of earth that goes on without minding. We manage to fret quite a bit after all as we do our own gathering of important things, though god knows to what real purpose.

This is a small film that will appear at times purposeless or addled, in that Varda doesn't aspire for more than what the ground will turn up for her, but she picks it all up with care and has fun with it. She doesn't just see a social issue here and we're better off for it. How much richer the landscape of film would be if more filmmakers would just go out with a cheap camcorder? It isn't the topical subject, any TV crew could film that, it's gracing us with a way of seeing.

There's a French history of "gleaning" that she references via paintings of women picking up wheat in the fields, that is of course her entry into images of life she gleans with her camera, herself a gatherer, but in another way it is to situate what we see as a certain rite of life with its continuity, something that people do.

So I like that we're called to see beyond desperation here, though at a glance many of these lives will seem dismal. Varda has taken an interest in itinerant lives for a long time as previous films by her suggest, Vagabond most notably, and she has the sensitivity of empathizing. We do see a few troubled individuals, because life kind of swung that way before they had a chance to hold on perhaps. But we also see a life that manages just fine for itself and roots itself in the other, something like the anti-ego philosophy of one of the people in the film.

None of them are vexed to live as they do, that we see anyway, and it manages to remind me of the ancient Taoist injunctions to forego the anxieties for "humanity" and "responsibility", often hypocritical, and make yourself like a clump of earth that goes on without minding. We manage to fret quite a bit after all as we do our own gathering of important things, though god knows to what real purpose.

This is a small film that will appear at times purposeless or addled, in that Varda doesn't aspire for more than what the ground will turn up for her, but she picks it all up with care and has fun with it. She doesn't just see a social issue here and we're better off for it. How much richer the landscape of film would be if more filmmakers would just go out with a cheap camcorder? It isn't the topical subject, any TV crew could film that, it's gracing us with a way of seeing.

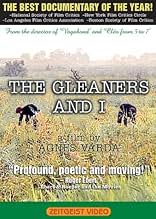

You may remember director Agnès Varda from her 1986 film, VAGABOND. But over the last five decades, the `grandmother of French New Wave' has completed 29 other works, most showing her affection, bemusement, outrage, and wide-ranging curiosity for humanity.

Varda's most recent effort-the first filmed with a digital videocamera-focuses on gleaners, those who gather the spoils left after a harvest, as well as those who mine the trash. Some completely exist on the leavings; others turn them into art, exercise their ethics, or simply have fun. The director likens gleaning to her own profession-that of collecting images, stories, fragments of sound, light, and color.

In this hybrid of documentary and reflection, Varda raises a number of philosophical questions. Has the bottom line replaced our concern with others' well-being, even on the most essential level of food? What happens to those who opt out of our consumerist society? And even, What constitutes--or reconstitutes--art?

Along this road trip, she interviews plenty of French characters. We meet a man who has survived almost completely on trash for 15 years. Though he has a job and other trappings, for him it is `a matter of ethics.' Another, who holds a master's degree in biology, sells newspapers and lives in a homeless shelter, scavenges food from market, and spends his nights teaching African immigrants to read and write.

Varda is an old hippie, and her sympathies clearly lie with such characters who choose to live off the grid. She takes our frenetically consuming society to task and suggests that learning how to live more simply is vital to our survival.

At times we can almost visualize her clucking and wagging her finger-a tad heavy-handedly advancing her agenda. However, the sheer waste of 25 tons of food at a clip is legitimately something to cluck about. And it is her very willingness to make direct statements and NOT sit on the fence that Varda fans most enjoy, knowing that her indignation is deeply rooted in her love of humanity.

The director interjects her playful humor as well-though it's subtle, French humor that differs widely from that of, say, Tom Green. Take the judge in full robes who stands in a cabbage field citing the legality of gleaning chapter and verse.

Quirky and exuberant, Varda, 72, is at an age where she's more concerned with having fun with her craft than impressing anyone. With her handheld digital toy, she pans around her house and pauses to appreciate a patch of ceiling mold. When she later forgets to turn off her camera, she films `the dance of the lens cap.'

One of the picture's undercurrents is the cycle of life-growth, harvest, decay. She often films her wrinkled hands and speaks directly about her aging process, suggesting that her own mortality is much on her mind. The gleaners pluck the fruits before their decay, as Varda lives life to the fullest, defying the inevitability of death. Toward the movie's end, she salvages a Lucite clock with no hands. As she films her face passing behind it, she notes, `A clock with no hands is my kind of thing.'

If you'd be the first to grab a heart-shaped potato from the harvest, or make a pile of discarded dolls into a totem pole, THE GLEANERS is probably your kind of thing.

Varda's most recent effort-the first filmed with a digital videocamera-focuses on gleaners, those who gather the spoils left after a harvest, as well as those who mine the trash. Some completely exist on the leavings; others turn them into art, exercise their ethics, or simply have fun. The director likens gleaning to her own profession-that of collecting images, stories, fragments of sound, light, and color.

In this hybrid of documentary and reflection, Varda raises a number of philosophical questions. Has the bottom line replaced our concern with others' well-being, even on the most essential level of food? What happens to those who opt out of our consumerist society? And even, What constitutes--or reconstitutes--art?

Along this road trip, she interviews plenty of French characters. We meet a man who has survived almost completely on trash for 15 years. Though he has a job and other trappings, for him it is `a matter of ethics.' Another, who holds a master's degree in biology, sells newspapers and lives in a homeless shelter, scavenges food from market, and spends his nights teaching African immigrants to read and write.

Varda is an old hippie, and her sympathies clearly lie with such characters who choose to live off the grid. She takes our frenetically consuming society to task and suggests that learning how to live more simply is vital to our survival.

At times we can almost visualize her clucking and wagging her finger-a tad heavy-handedly advancing her agenda. However, the sheer waste of 25 tons of food at a clip is legitimately something to cluck about. And it is her very willingness to make direct statements and NOT sit on the fence that Varda fans most enjoy, knowing that her indignation is deeply rooted in her love of humanity.

The director interjects her playful humor as well-though it's subtle, French humor that differs widely from that of, say, Tom Green. Take the judge in full robes who stands in a cabbage field citing the legality of gleaning chapter and verse.

Quirky and exuberant, Varda, 72, is at an age where she's more concerned with having fun with her craft than impressing anyone. With her handheld digital toy, she pans around her house and pauses to appreciate a patch of ceiling mold. When she later forgets to turn off her camera, she films `the dance of the lens cap.'

One of the picture's undercurrents is the cycle of life-growth, harvest, decay. She often films her wrinkled hands and speaks directly about her aging process, suggesting that her own mortality is much on her mind. The gleaners pluck the fruits before their decay, as Varda lives life to the fullest, defying the inevitability of death. Toward the movie's end, she salvages a Lucite clock with no hands. As she films her face passing behind it, she notes, `A clock with no hands is my kind of thing.'

If you'd be the first to grab a heart-shaped potato from the harvest, or make a pile of discarded dolls into a totem pole, THE GLEANERS is probably your kind of thing.

The Gleaners and I is odd in that it hardly feels like a proper film at all: it's shot on visibly cheap MiniDV, its editing is consistently unpolished, and it delights in crossing the line from personal to indulgent in excess. It's obvious that these are all deliberate choices; the question is, would we care if it didn't have the name Agnès Varda on it?

Ultimately, the film's amateurish style is somewhat deceptive: Varda demonstrates her talent for finding significance in the mundane, and strikes a number of compelling parallels in her examination of scavenger culture. The film does tend to coast on Varda's legendary new wave status at times, particularly as we linger on interviews and segments only tenuously related to the film's subject, but it's interesting as an example of a living legend embracing her medium's democratization: for all the good and bad it implies, she blends in seamlessly with the millions of talented people who own camcorders. -TK 10/21/10

Ultimately, the film's amateurish style is somewhat deceptive: Varda demonstrates her talent for finding significance in the mundane, and strikes a number of compelling parallels in her examination of scavenger culture. The film does tend to coast on Varda's legendary new wave status at times, particularly as we linger on interviews and segments only tenuously related to the film's subject, but it's interesting as an example of a living legend embracing her medium's democratization: for all the good and bad it implies, she blends in seamlessly with the millions of talented people who own camcorders. -TK 10/21/10

There are a number of reasons why I enjoyed this movie.

1.) I am into etymology. Most english words come through French through Latin and it was fun to attempt to match spoken word and subtitle.

2.) French rap. I am very much interested in the hip hop subculture and was amazed how similar theirs is to ours.

3.) Scenic shots. There were: orchards, fields, barren highways, a gypsie camp, a great many paintings, "junk" yards, and such.

4.) The camera shots. The journal/documentary filming allowed for several film taboos to be artfully waived. For example, the directors hands often purposefully find themselves in a shot, these were my favorite parts because of the witticisms she gave at these times. Also, an accidental shot were the camera lense gets in the way was made into another piece of ordinary object art.

5.) Also, I was intrigued by the comparison between classical gleaning, modern gleaning, and modern scavenging. See Dark Days for another good real life scavenger flick.

6.) Lastly, I felt a connection with many of the characters. People who were on the fringe of society and enjoyed it. Specifically, there were a few who had jobs and apartments, but still chose to rumage through old trash for their meals. "I've been living off trash for 10 years and I haven't been sick once," as on of them candidly stated.

Note - For me, these 6 items more than made this movie an enjoyable experience, but this is basically all there is, so be warned: There is no plot! Really it is just a bunch of stuff that happens, but feel that this helps the movie more than hurts.

1.) I am into etymology. Most english words come through French through Latin and it was fun to attempt to match spoken word and subtitle.

2.) French rap. I am very much interested in the hip hop subculture and was amazed how similar theirs is to ours.

3.) Scenic shots. There were: orchards, fields, barren highways, a gypsie camp, a great many paintings, "junk" yards, and such.

4.) The camera shots. The journal/documentary filming allowed for several film taboos to be artfully waived. For example, the directors hands often purposefully find themselves in a shot, these were my favorite parts because of the witticisms she gave at these times. Also, an accidental shot were the camera lense gets in the way was made into another piece of ordinary object art.

5.) Also, I was intrigued by the comparison between classical gleaning, modern gleaning, and modern scavenging. See Dark Days for another good real life scavenger flick.

6.) Lastly, I felt a connection with many of the characters. People who were on the fringe of society and enjoyed it. Specifically, there were a few who had jobs and apartments, but still chose to rumage through old trash for their meals. "I've been living off trash for 10 years and I haven't been sick once," as on of them candidly stated.

Note - For me, these 6 items more than made this movie an enjoyable experience, but this is basically all there is, so be warned: There is no plot! Really it is just a bunch of stuff that happens, but feel that this helps the movie more than hurts.

To glean is to see something beautiful or useful in something that is conventionally useless, pointless or ugly, and to make that thing even more beautiful or useful. One can consume the stuff they glean, or they could recycle it into an art form, creating a whole new purpose for the object(s). Gleaning also applies to our basic ability for survival. In the worst times of our lives, whether it's the death of a friend or facing poverty or illness, there is a way of seeing things positively that helps us survive. Thus, faith and hope are gleaned in the face of disparity. Scientists glean facts and turn them into theory. We glean possibilities every time we use our imaginations. We glean memories when we write (James Joyce was probably the world's greatest literary gleaner). And psychiatrists pay attention to what others don't notice by gleaning beneath the stubborn surface of our egos. This film blew me away in how it depicted how much waste our society makes, and the myriad of ways in which those who glean what we discard benefit society. But the film is even more than a fascinating documentary and social statement. As one can see from the concepts listed above, it's also a celebration of seeing our world and ourselves as a "cluster of possibilities." There are many theories that we are all in essence stardust developed from fragments of 'the big bang' and quintessentially, this film is about "gleaners of stardust." It pertains to those who metaphorically glean the hidden mysteries and possibilities of our world (i.e. the gleaners of dreams and ideas). Come to think of it, film lovers and the best filmmakers are in fact, gleaners by that very definition. Agnes Varda has proved that she is one of the greatest gleaners of all time.

Lo sapevi?

- QuizThe film was included for the first time in 2022 on the critics' poll of Sight and Sound's list of the greatest films of all time, at number 67.

- Citazioni

Agnès Varda: He looked at an empty clock but put it back down. I picked it up and took it home. A clock without hands works fine for me. You don't see time passing.

- Colonne sonoreApfelsextett

Composed by Pierre Barbaud

I più visti

Accedi per valutare e creare un elenco di titoli salvati per ottenere consigli personalizzati

- How long is The Gleaners & I?Powered by Alexa

Dettagli

- Data di uscita

- Paese di origine

- Lingua

- Celebre anche come

- Les glaneurs et la glaneuse

- Luoghi delle riprese

- Azienda produttrice

- Vedi altri crediti dell’azienda su IMDbPro

Botteghino

- Lordo Stati Uniti e Canada

- 155.320 USD

- Fine settimana di apertura Stati Uniti e Canada

- 12.655 USD

- 11 mar 2001

- Lordo in tutto il mondo

- 159.165 USD

- Tempo di esecuzione1 ora 22 minuti

- Colore

- Proporzioni

- 1.33 : 1

Contribuisci a questa pagina

Suggerisci una modifica o aggiungi i contenuti mancanti

Divario superiore

By what name was La vita è un raccolto (2000) officially released in India in English?

Rispondi