Berlino, tardi anni venti. Franz Biberkopf, colpevole dell'omicidio della sua amante, esce di prigione e decide di condurre una vita onesta. Presto però comincia a bere, si chiude in se stes... Leggi tuttoBerlino, tardi anni venti. Franz Biberkopf, colpevole dell'omicidio della sua amante, esce di prigione e decide di condurre una vita onesta. Presto però comincia a bere, si chiude in se stesso e precipita in un mondo di malaffare.Berlino, tardi anni venti. Franz Biberkopf, colpevole dell'omicidio della sua amante, esce di prigione e decide di condurre una vita onesta. Presto però comincia a bere, si chiude in se stesso e precipita in un mondo di malaffare.

- Premi

- 2 vittorie e 4 candidature totali

Sfoglia gli episodi

Recensioni in evidenza

Very long (15 hours in all), very worth seeing. Based on Alfred Doeblin's novel of the same name, "Berlin Alexanderplatz" is set in and around Berlin during the Weimar Republic era, the decade immediately preceding the establishment Hitler's Third Reich in 1933.

The workers of '20s Berlin are taking it on the chin. Mass unemployment reigns alongside the greed of the landlord and capitalist classes. People are reacting and acting in various ways to survive. As usual, some of the unemployed turn to crime; others to prostitution. Most of the film's cast will see the dawn of the "thousand year Reich" with their eyes only half way open.

But life must go on and it will go on and it does go on in Berlin during Weimar. It's an exciting time as well, a time when the puritanism of the countryside is being exchanged for a chance to live free and wild in a sleepless city chock full of cabarets and kniepe. Of course, the Nazis didn't like this and neither did their supporters, the conservative majorities of rural Germany.

As the film's director,R.W. Fassbinder put it,Doeblin's novel,BERLIN ALEXANDERPLATZ, "offered a precise characterization of the twenties; for anyone who knows what came of all that, it's fairly easy to recognize the reasons that made the average German capable of embracing his National Socialism."

All this turmoil and potential for explosive change are seen by the audience of "Berlin Alexanderplatz" through the eyes of one guy, Franz Biberkopf. Walk, ride, rob, love, drink and despair with Franz Biberkopf. Best bring along a case or two of good lager while you're immersing yourself in the prelude to "Gotterdamerung".

The workers of '20s Berlin are taking it on the chin. Mass unemployment reigns alongside the greed of the landlord and capitalist classes. People are reacting and acting in various ways to survive. As usual, some of the unemployed turn to crime; others to prostitution. Most of the film's cast will see the dawn of the "thousand year Reich" with their eyes only half way open.

But life must go on and it will go on and it does go on in Berlin during Weimar. It's an exciting time as well, a time when the puritanism of the countryside is being exchanged for a chance to live free and wild in a sleepless city chock full of cabarets and kniepe. Of course, the Nazis didn't like this and neither did their supporters, the conservative majorities of rural Germany.

As the film's director,R.W. Fassbinder put it,Doeblin's novel,BERLIN ALEXANDERPLATZ, "offered a precise characterization of the twenties; for anyone who knows what came of all that, it's fairly easy to recognize the reasons that made the average German capable of embracing his National Socialism."

All this turmoil and potential for explosive change are seen by the audience of "Berlin Alexanderplatz" through the eyes of one guy, Franz Biberkopf. Walk, ride, rob, love, drink and despair with Franz Biberkopf. Best bring along a case or two of good lager while you're immersing yourself in the prelude to "Gotterdamerung".

Berlin Alexanderplatz is by far the most ambitious film of all time. It has a very unusual feel to it as it slips between the real world and the mental state of Franz Biberkopf (particularly when he relives again and again the crime which landed him in prison). Of special interest to film addicts who have not seen the movie is the final 90 minutes which evidently was Fassbinder's own filmed fantasy of the entire plot, done with a background picture of Hieronymus Bosch's "The Garden of Earthly Delights." A fabulous richly-detailed film, but some may not be able to get past the politics.

10hasosch

The most unique contribution of film director Rainer Werner Fassbinder to Alfred Döblin's novel "Berlin Alexanderplatz. The story of Franz Biberkopf" (1929) was his interpretation of the relationship between Franz Biberkopf and Reinhold as a love story. Therefore, in Fassbinder's interpretation, Franz Biberkopf's accident is seen as self-mutilation. In Fassbinder's last movie, Querelle (1982), we will hear the confession: "To kiss a man is like the confrontation with one's own face in the mirror". As different as Döblin's "Alexanderplatz" and Genet's "Querelle" may be, the two novels are alike because they meet one another like an object and its mirror image: the first novel deals with the good-guy Franz Biberkopf who is ruined by his love to humankind, and the other novel with the immoral murderer Querelle by which those who love him, perish.

Like many of Fassbinder's movies, "Berlin Alexanderplatz", too, shows clear autobiographical traces. Fassbinder said about the three protagonists Franz, Reinhold and Mieze: "All three together supply my chance to survive". As Fassbinder pointed out in his article "The cities of the human and his soul", unlike Döblin in his original novel, Fassbinder is not so much interested in the discovery of the outer reality of Berlin, but concentrates on their inhabitants. "Berlin Alexanderplatz" is a journey into the souls of different people under the conviction that the reign of subjectivity of the inner realities is much bigger than the reign of the objective reality outside. As a matter of fact (as has been pointed out by several commentators), "Berlin Alexanderplatz" with its almost 100 roles gave Fassbinder the possibility to let appear in his movie practically every person who had been crucial in his own life. That he split himself over three persons (Franz, Reinhold, Mieze) is very typical in Fassbinder's work in which many persons have their Alter Egos (e.g., "Despair", 1977). As Fassbinder had pointed out in an interview: "Despair is the only condition of life that I can accept". Consistently, the movie shows the systematic destruction of Franz, since "he is an anarchical figure in a crowd of social beings, and in the end, he perishes because of that". In fifteen and half an hour, we can analyze "the constellations, how a human spoils his life by a certain incapability which he developed by his upbringing" (Fassbinder). The movie shows the shaping of Franz Biberkopf to a mentally destroyed but therefore useful member of society. Every connoisseur of Fassbinder's work will be remembered to the final scene of "Fear of Fear" (1975) in which Margot, after having been "cured" in a psychiatric clinic, types addresses on envelopes like a trained monkey. When Karli brings her the information that their neighbor, the depressive Mr. Bauer, has killed himself, she hardly recognizes this fact anymore telling to Karli that she is feeling fine.

Like many of Fassbinder's movies, "Berlin Alexanderplatz", too, shows clear autobiographical traces. Fassbinder said about the three protagonists Franz, Reinhold and Mieze: "All three together supply my chance to survive". As Fassbinder pointed out in his article "The cities of the human and his soul", unlike Döblin in his original novel, Fassbinder is not so much interested in the discovery of the outer reality of Berlin, but concentrates on their inhabitants. "Berlin Alexanderplatz" is a journey into the souls of different people under the conviction that the reign of subjectivity of the inner realities is much bigger than the reign of the objective reality outside. As a matter of fact (as has been pointed out by several commentators), "Berlin Alexanderplatz" with its almost 100 roles gave Fassbinder the possibility to let appear in his movie practically every person who had been crucial in his own life. That he split himself over three persons (Franz, Reinhold, Mieze) is very typical in Fassbinder's work in which many persons have their Alter Egos (e.g., "Despair", 1977). As Fassbinder had pointed out in an interview: "Despair is the only condition of life that I can accept". Consistently, the movie shows the systematic destruction of Franz, since "he is an anarchical figure in a crowd of social beings, and in the end, he perishes because of that". In fifteen and half an hour, we can analyze "the constellations, how a human spoils his life by a certain incapability which he developed by his upbringing" (Fassbinder). The movie shows the shaping of Franz Biberkopf to a mentally destroyed but therefore useful member of society. Every connoisseur of Fassbinder's work will be remembered to the final scene of "Fear of Fear" (1975) in which Margot, after having been "cured" in a psychiatric clinic, types addresses on envelopes like a trained monkey. When Karli brings her the information that their neighbor, the depressive Mr. Bauer, has killed himself, she hardly recognizes this fact anymore telling to Karli that she is feeling fine.

Saw in theatre on release, and the many-VHS set, and to this day still rank it unquestionably among top 10 of all time (even with the sometimes overly heavy Fassbinder spin).

The duration permits a whole new level of dramatic depth, as well as a story with many small and one big arc. Acting, music, photography, dialog - all a treat. Ending is love-it-or-hate-it (I didn't hate it).

Subtitles are about 75% legible on video, and were about 90% discernible in the theatre. Audio was often very loud - comes out kind of 'harsh' - wasn't as bad in the theatre.

After each several 'episodes' you'll have to go for a walk (equally so for the legs and the psyche)!

The duration permits a whole new level of dramatic depth, as well as a story with many small and one big arc. Acting, music, photography, dialog - all a treat. Ending is love-it-or-hate-it (I didn't hate it).

Subtitles are about 75% legible on video, and were about 90% discernible in the theatre. Audio was often very loud - comes out kind of 'harsh' - wasn't as bad in the theatre.

After each several 'episodes' you'll have to go for a walk (equally so for the legs and the psyche)!

First the positive. Fassbinder's direction is superb - The camera glides expressively from one composition to another, always precise, revealing, artistic. No amount of effort is spared in the creation of these shifting compositions; the intelligence and sensitivity of the camera contributes as much as the words do to character and meaning. There's also a terrific intensity about it. The performances of the main players are remarkable Fassbinder seems to be squeezing them like lemons.

This still disappointed though. I expected something richer, quirkier, funnier, more meaningful in short, smarter. Surprisingly, this plays it perfectly straight, which in itself causes confusion. It was hard to believe that our man Biberkopf was supposed to be a totally well-meaning chap, or that Mietze was just a silly good-natured girl. Seriously misled by the unrelentingly sombre, murky atmosphere, we are inclined to look (mistakenly) for deeper, darker things in everyone.

On his release from prison at the beginning Biberkopf comes across as barely sane, if not totally deranged, violent and immoral. He vows to make amends and lead a good life but he never really endears himself to us after that brutal introduction. He's as thick as two planks, he's fat, certainly not good looking, for much of the story he only has one arm, he is often cantankerous and easily goes off his head completely he's a klutz and a galumph. I didn't much like Biberkopf to begin with and barely did so by the end when I finally realised I was supposed to.

Bizarrely, Biberkopf attracts a constant succession of doting women. These women, though they are viewed mainly as chattels, are the most interesting characters in the film, but one suspects that both Doblin and Fassbinder really don't understand heterosexual women at all. Quite what these beautiful women see in Biberkopf is a mystery, and it frustrates our efforts to understand him and what the film is about.

Fassbinder extracts amazing performances in what a was a very quick shoot for its length. Gunther Lamprecht as Biberkopf dominates the film but something of this length really needs more than one focus.

The length is another major problem. There is simply no reason for this to be so long in terms of both the narrative and the meaning in fact the length works against both. Rather than giving itself time to breath, it often allows itself to tire. Almost every scene could have been done more economically. It is easy to identify entire scenes which could have been skipped, especially the repetitive ones.

The next problem is the gauzy sepia effect which, wearyingly, is maintained throughout. This creates an antique world remote in time and relevance, as if we are looking at people already dead and gone, an old photograph full of forgotten faces. This distances us both visually (apart from the grimy overlay, we are often looking through murky windows or reflections in tarnished mirrors) and emotionally. The lack of humour is another problem. Not a single laugh in a film of this length? Not even irony?

The narrative seems aimless in places due to repetition and lack of notable events. Apart from Biberkopf's stint at selling shoe-laces (one of the best sections), his various jobs are monumentally dull (such as standing in the U-bahn selling newspapers). There is one particularly tedious episode when he gets involved in politics. The last two episodes are much the best, when Gottfried John's diffident gangster Reinhold really comes to the fore. Reinhold is a much more complex and interesting character than Biberkopf. There is an extraordinary scene in which he lures Biberkopf's girl into a liason in the forest which shows us aspects of human nature that rocks our notions of propriety, skewing and denting human behaviour into barely recognisable shape. The scene is long and intense but it's memorable and is the only scene of real value and interest you might extract from the entire film.

Homosexual aspects are present but kept in the background. Biberkopf has a tender relationship with his old friend Meck, whose every appearance brings forth a melancholy (and woefully predictable) leitmotif as the two men stare deeply at each other. There are also strong hints that Biberkopf is emotionally attached to Reinhold despite the disaster that the man wreaks on his life. Perhaps therein lay the seed that attracted Fassbinder to the story self-destruction through a relationship that dare not speak its name does not even acknowledge its existence.

The music, characterised by a mournful trumpet solo unfortunately transported me to Yorkshire each time. Meck in particular looked like he'd stepped out of Last of the Summer Wine, and from what we saw of Berlin, this could easily have been Leeds. The mise en scene partly thanks to the murky visuals - is mainly oppressive. In general, the early critics were right, it is all too dark on the eye.

In conclusion, an overlong adaptation of a novel that clearly is more concerned with literary fireworks than cogent observations on life. Some big mistakes were made in the mise-en-scene that almost made the film unwatchable, but it is generally redeemed by brilliant direction and acting.

This still disappointed though. I expected something richer, quirkier, funnier, more meaningful in short, smarter. Surprisingly, this plays it perfectly straight, which in itself causes confusion. It was hard to believe that our man Biberkopf was supposed to be a totally well-meaning chap, or that Mietze was just a silly good-natured girl. Seriously misled by the unrelentingly sombre, murky atmosphere, we are inclined to look (mistakenly) for deeper, darker things in everyone.

On his release from prison at the beginning Biberkopf comes across as barely sane, if not totally deranged, violent and immoral. He vows to make amends and lead a good life but he never really endears himself to us after that brutal introduction. He's as thick as two planks, he's fat, certainly not good looking, for much of the story he only has one arm, he is often cantankerous and easily goes off his head completely he's a klutz and a galumph. I didn't much like Biberkopf to begin with and barely did so by the end when I finally realised I was supposed to.

Bizarrely, Biberkopf attracts a constant succession of doting women. These women, though they are viewed mainly as chattels, are the most interesting characters in the film, but one suspects that both Doblin and Fassbinder really don't understand heterosexual women at all. Quite what these beautiful women see in Biberkopf is a mystery, and it frustrates our efforts to understand him and what the film is about.

Fassbinder extracts amazing performances in what a was a very quick shoot for its length. Gunther Lamprecht as Biberkopf dominates the film but something of this length really needs more than one focus.

The length is another major problem. There is simply no reason for this to be so long in terms of both the narrative and the meaning in fact the length works against both. Rather than giving itself time to breath, it often allows itself to tire. Almost every scene could have been done more economically. It is easy to identify entire scenes which could have been skipped, especially the repetitive ones.

The next problem is the gauzy sepia effect which, wearyingly, is maintained throughout. This creates an antique world remote in time and relevance, as if we are looking at people already dead and gone, an old photograph full of forgotten faces. This distances us both visually (apart from the grimy overlay, we are often looking through murky windows or reflections in tarnished mirrors) and emotionally. The lack of humour is another problem. Not a single laugh in a film of this length? Not even irony?

The narrative seems aimless in places due to repetition and lack of notable events. Apart from Biberkopf's stint at selling shoe-laces (one of the best sections), his various jobs are monumentally dull (such as standing in the U-bahn selling newspapers). There is one particularly tedious episode when he gets involved in politics. The last two episodes are much the best, when Gottfried John's diffident gangster Reinhold really comes to the fore. Reinhold is a much more complex and interesting character than Biberkopf. There is an extraordinary scene in which he lures Biberkopf's girl into a liason in the forest which shows us aspects of human nature that rocks our notions of propriety, skewing and denting human behaviour into barely recognisable shape. The scene is long and intense but it's memorable and is the only scene of real value and interest you might extract from the entire film.

Homosexual aspects are present but kept in the background. Biberkopf has a tender relationship with his old friend Meck, whose every appearance brings forth a melancholy (and woefully predictable) leitmotif as the two men stare deeply at each other. There are also strong hints that Biberkopf is emotionally attached to Reinhold despite the disaster that the man wreaks on his life. Perhaps therein lay the seed that attracted Fassbinder to the story self-destruction through a relationship that dare not speak its name does not even acknowledge its existence.

The music, characterised by a mournful trumpet solo unfortunately transported me to Yorkshire each time. Meck in particular looked like he'd stepped out of Last of the Summer Wine, and from what we saw of Berlin, this could easily have been Leeds. The mise en scene partly thanks to the murky visuals - is mainly oppressive. In general, the early critics were right, it is all too dark on the eye.

In conclusion, an overlong adaptation of a novel that clearly is more concerned with literary fireworks than cogent observations on life. Some big mistakes were made in the mise-en-scene that almost made the film unwatchable, but it is generally redeemed by brilliant direction and acting.

Lo sapevi?

- QuizThis was screened at the Vista cinema in Hollywood in August 1983, in its entirety (with a 2 hour break for dinner), making it the longest film ever to be commercially screened (15 hours, 21 minutes). Heimat (1984), which is only a little longer at 15 hours and 40 minutes was shown in German cinemas and at the London Film Festival, but not in a single screening, instead being split across a weekend with a night in between the first and second parts.

- ConnessioniEdited into 365 days, also known as a Year (2019)

I più visti

Accedi per valutare e creare un elenco di titoli salvati per ottenere consigli personalizzati

Dettagli

- Data di uscita

- Paesi di origine

- Lingua

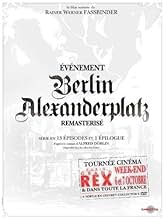

- Celebre anche come

- Berlín Alexanderplatz

- Luoghi delle riprese

- Aziende produttrici

- Vedi altri crediti dell’azienda su IMDbPro

Contribuisci a questa pagina

Suggerisci una modifica o aggiungi i contenuti mancanti