Aggiungi una trama nella tua linguaA day in the life of a Parisian housewife/prostitute, interspersed with musings on the Vietnam War and other contemporary issues.A day in the life of a Parisian housewife/prostitute, interspersed with musings on the Vietnam War and other contemporary issues.A day in the life of a Parisian housewife/prostitute, interspersed with musings on the Vietnam War and other contemporary issues.

- Regia

- Sceneggiatura

- Star

- Premi

- 1 candidatura in totale

- Narrator

- (voce)

- Young Man

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

- Girl Talking to Robert

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

- Girl in Bath

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

- Christophe Jeanson

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

- Meter Reader

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

- Marianne

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

- Monsieur Gehrard

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

- Girl

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

- Man in Basement

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

- Author

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

- Pécuchet

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

- John Bogus

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

- Woman in Basement

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

- Bouvard

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

- Robert Jeanson

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

- Roger

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

Recensioni in evidenza

Non-sequiturial loose-ends of non-communication between the characters, and conversations between the actors and the director which we are not allowed to follow.

Uncommunicative and unengaged philosophico-political maunderings of citizens who are floundering conceptually in a system that cannot sustain them, either morally or intellectually.

A view of Parisian building-sites as a social upheaval which yet represents the antithesis of any structural or constructivist manifestation of social progress.

A film that is, like the capitalist society that has the eye of the camera hypnotised, a profoundly blank and alienating surface, whose technique is only occasionally relieved by gratuitous scenes of meaning:

E.g. -

A woman trapped in a sink estate and yearning to be free, who is compelled by the desparation of her dream to entrap and enslave herself even further through prostitution;

The intrusion of a pimp-like meter-reader into the pure nakedness of private space;

A creche in a brothel;

A secular catechesis - The simple, non-sexual, non-manipulative dialectic of honest exploration that makes us human;

The still-birth of revolutionary thought as the spiral galaxy in a coffee-cup ...

All-in-all, the representation of a society which is profoundly inhospitable to the human beings who should constitute it, and which consequently does not permit the realisation of any aspect of humanity.

All we get are fugitive glimpses of life in the process of moral and intellectual decay. Thought and character remains unrealised, and the film is therefore also inchoate as the necessary reflection of this social unreality.

Here is a wan world, haemmoraging meaning as we watch. Here before us are the helpless ghosts of an industrial medium. They dance fitfully in the unchanging wind, the fantastic commercial simulacra in which we bind our free nature.

Strips of film, strung out like human fly-paper, where fluttering images stick only as they die. In place of creative pressure, an air of ennui, of carelessness: A drop-out film - a film of drop-outs, plot-holes in the threadbare social fabric, - neglectful of all appearances. The face of the film gazes basilisk-like out upon the viewer, resentful of our settled habits of non-involvement. Two frozen gazes cancel, the mutual incomprehension only verging on hostile irritation. No reaction. No drama. The light dies.

The hypnotic mirror of reproach whose conscience we yearn to assuage, that traps our humanity in the voyeur's dream, as it is projected back upon us in the Gorgon's gaze.

Desire is petrified - one's petty film-going expectations of this penetration of dark places disappointed. One escapes from the deathly spell of cinema into the real world.

Godard's lesson is that there is nothing meaningful in this cave of artificial shadows, and that he will bitterly wean us from our facile consumerist dreams, that we may the better engage with the harsh political realities of life.

The radically disillusioned auteur deconstructs himself. Le derniere vague flops exhausted on that endless strip where empty sprocket-holes run on aimlessly towards a dying sun.

The mechanism of dreams runs down.

We are not automata - we are made up by life. To live is the story we enact, without intermediary, and unmediated. The immediate and the authentic are alien to art. Art is a whispering empty shell left high and dry. Life is not the element of dead things: Do not listen to the shallow siren voice of le faux vague! Plunge back into humanity's proper medium.

Thus does a revolution in seeing strip out the gelatinous scales of our burned-out eyes, and there is no more interference with the wavelengths of light being broadcast from the nearest star.

Thus do the sighing bones of life articulate the bounds of existence.

We are the tides that wax and wane - the ocean that overwhelms itself, drowning its own waves in one flood of being.

Godard's film and films are under the influence of this larger movement. With his work, we are cast adrift from all anchors and familiar landmarks. We are 'all at sea'. There is a transition - a movement that is perhaps nearer to momentum than inertia - from whence we cannot recall to whither we cannot see. His is the ultimate cinema of flux.

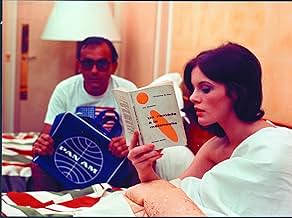

There is little plot to the film, and instead Godard uses every film-making technique in his arsenal to take the audience on a journey through the Paris suburbs, having his characters delve into rambling monologues, often responding to questions or regurgitating lines fed through an ear-piece by Godard himself. The main focus is Juliette (Marina Vlady), who occasionally prostitutes herself so she can buy pretty clothes or perhaps just to relieve herself of the boredom of the consumerist lifestyle, while her husband Robert (Roger Monsoret) listens to speeches on the radio regarding America's involvement in Vietnam.

It's with his over-simplified characterisation of Juliette that 2 or 3 Things fails to hit the mark. She is beautiful and intelligent, but seems to only truly love shopping or catching the eye of a handsome man in a cafe. There's little of the free-spirited charisma that Karina embodied in her various roles under Godard, but perhaps that's the point. Themes are often explored with a remarkable lack of subtlety, with the director's obvious opposition to the illegal war in Vietnam cropping up many times throughout the film, with photographs of victims of the war spliced into a rather silly scene involving an 'American' photographer (with a heavy French accent) and his odd fetish with placing bags over ladies heads and having them act out a routine.

Far more impressive are the visuals, with the celebrated shot of a swirling espresso while Godard whispers about his own inadequacy being the most memorable image, and the sheer ambition of a project shot so quickly. Godard is both criticised and adorned for being simply too intellectual and obtuse for film, and 2 or 3 Things is one of the greatest examples of his unwillingness to craft a digestible film for his select audience. The dialogue is often wonderful and poetic, yet sometimes it's rambling nonsense, spoken by characters who have no place in the story, almost as if Godard got bored and moved his camera to a conversation he found more interesting. It's both frustrating and fascinating to see a director of such singular vision, and while there is little of the excitement and energy of his early New Wave work, 2 or 3 Things is an experience like no other.

French's student movement turned into something of a cinema movement. To a small group of devoted young cinephiles, French film seemed like a cheap art - one capable of so much more but settled for so very little. Nobody seemed to want to experiment or toy with the medium in anyway. That is until Godard hit the scene, boasting a more assured and confident enigma and housing extremely radical and challenging themes and stylistic choices few had seen before.

I equate Godard's films to bad sex because it isn't until after watching them and reading a few thoughts by a miscellaneous bunch online do I realize if I liked them or not. His films are challenging because while watching them, you're sometimes lost in what they're trying to convey. But once you find an idea or some aesthetic attributes to latch on to, dissecting the film is a much easier process. In that respect, Godard's films may also be like an algebra test.

2 or 3 Things I Know About Her, however, is sex I never got around to fully enjoying and an algebra test I was never able to pass in the long-run. The film is nowhere near as indescribable or as impossibly vague and empty as Godard's latest work Film Socialisme, but its ability to baffle even fifty years late still holds true. This is a cinematic enigma like few others with sequences ranging from digestible and accessible to a complete mystery on my behalf.

What little coherent narrative there is focuses on Juliette Jeanson (Marina Vlady), a married bourgeois mother who begins her descent into prostitution. She drops her child off at a friend's who runs a business of watching the children of prostitutes before going about her day of shopping, cleaning the house, and meeting new clients. Godard's uniqueness in regard to the story is that he makes all of the sex lack any shred of eroticism and instead makes it rather silly (IE: a man makes a woman wear a shopping bag over her head).

Godard consistently interrupts this narrative with shots of whatever he feels like pointing the camera at with soft-spoken narration added over the images. Godard's narration often doesn't make a lot of sense, but his unpredictable comments and remarks provide the film with or feeling that he is watching this picture with us and giving his own commentary as it progresses.

During the time of 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her's release (1967 to be specific), Godard had become outspoken about his opposition towards Americanization and the ideas of the country as a whole. In the late sixties, prolific advertising began to turn up and, consequently, Godard saw this as an attack and began vocalizing his disdain for advertising. Frequently punctuating this particular picture are stray images of pop art, akin to the style Andy Warhol was famous for.

Of course, the meaning for the inclusions of these images is anyone's guess really. Godard makes his impressionistic style known and present and leaves us to form the thesis out of his work for ourselves it seems. This is one of the issues with this film as a whole. A film should never feel like it is handing you a series of clips and telling you to form an idea out of them without giving you a starting point or an anchor to latch on to. Even in the most impressionistic films by people like Ron Fricke or Gus Van Sant, there is a basic idea or concept that one can attach themselves to in order to try and form some ideas about the film's message.

Godard never seems to give us a starting point with 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her other than a compilation of clips that could very well have a deeper meaning if we knew just where the hell to begin. The pop art/advertising angle is something to go off of, but the film doesn't seem to focus on that nearly enough for it to be the main theme. And with that, even Juliette just seems like a character Godard includes to simply emphasize his appreciation and admiration for prostitutes.

As damning as 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her so often is, the film looks bright, crisp, and extremely clear thanks to the cinematography of Godard's frequent collaborator Raoul Coutard. Coutard gives the film a refined and aesthetically beautiful look, even if what he's showing us doesn't pack in a lot of clarity or real sense. As a film, 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her baffles beyond belief and fails at stringing together a coherent and digestible narrative. As an essay on film, it kinda works - if only I didn't have to cheat to figure out what could be an acceptable answer to it.

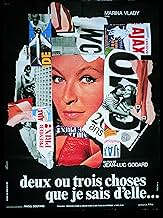

Starring: Marina Vlady. Directed by: Jean-Luc Godard.

Lo sapevi?

- QuizWhen Juliette drops off her daughter at the day care/brothel, there is a painting on the wall of a screen shot of Nana Kleinfrankenheim, portrayed by Anna Karina, in Questa è la mia vita (1962).

- Citazioni

Narrator: Since social relations are always ambiguous, since my thoughts divide as much as unite, and my words unite by what they express and isolate by what they omit, since a wide gulf separates my subjective certainty of myself from the objective truth others have of me, since I constantly end up guilty, even though I feel innocent, since every event changes my daily life, since I always fail to communicate, to understand, to love and be loved, and every failure deepens my solitude, since - since - since I cannot escape the objectivity crushing me nor the subjectivity expelling me, since I cannot rise to a state of being nor collapse into nothingness - I have to listen, more than ever I have to look around me at the world, my fellow creature, my brother.

- ConnessioniEdited into Notes pour Debussy - Lettre ouverte à Jean-Luc Godard (1988)

I più visti

Dettagli

Botteghino

- Lordo Stati Uniti e Canada

- 104.038 USD

- Fine settimana di apertura Stati Uniti e Canada

- 11.214 USD

- 19 nov 2006

- Lordo in tutto il mondo

- 104.038 USD

- Tempo di esecuzione1 ora 27 minuti

- Mix di suoni

- Proporzioni

- 2.35 : 1

Contribuisci a questa pagina