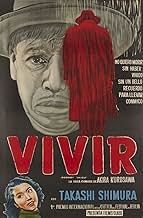

Un burocrate cerca di trovare un senso alla propria vita dopo aver scoperto di essere affetto da un cancro terminale.Un burocrate cerca di trovare un senso alla propria vita dopo aver scoperto di essere affetto da un cancro terminale.Un burocrate cerca di trovare un senso alla propria vita dopo aver scoperto di essere affetto da un cancro terminale.

- Regia

- Sceneggiatura

- Star

- Nominato ai 1 BAFTA Award

- 6 vittorie e 2 candidature totali

Recensioni in evidenza

Akira Kurosawa knew how to get in touch with human nature through his art. With his visual expressiveness and storytelling, he could pierce through his subjects, even in his big and occasionally comical samurai films, and find the elemental things do work. What he probably learned off of Rashomon probably helped out with Ikiru (To Live), a story of an old man who finds out he will die within a year, as both stories deal with perceptions of the significance of a life spent and a life wasted. Though that was to a different degree in Rashomon, with Ikiru Kurosawa expands into full-on existentialism.

The old man Kanji Watanabe (in a wholly believable and often heart-breaking performance by Takashi Shimura) knows his life hasn't amounted to much as a (chief) clerk for the city. He knows he hasn't had a great kinship with his son. He's accepting his fate with a heavy soul. One of the tenets of existentialism is that there's free-will, and the responsibility to accept what is done with one's life. Kurosawa might've (as I speculate, I don't entirely know) caught onto this for his lead, and it works, especially with the little details.

Such little details, unforgettable ones, have been expounded upon by other reviewers and critics, such as the drunken, sullen singing of "Life is short, fall in love my maiden" in the bar. A scene like that almost speaks for itself and yet it's also subtle. But one scene that had me was one not too many talk about. It's when Watanabe is in the Deputy Mayor's office, asking for permission so that a park can be built. At first the Mayor ignores him, but then Watanabe begs, but not in a way that manipulates the audience for sympathy with the old man. The mayor must be sensing something in his eyes, desperate and weak, however determined, and it's something that probably most of the audience can identify with as well, even if they don't entirely identify with the character.

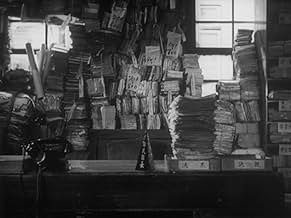

But aside from the emotional impact Ikiru can have on a viewer, composition-wise (with the help of Asakazu Nakai, wonderful cinematographer on less than a dozen Kurosawa films) and editing-wise the film is ahead of its time and another example of Kurosawa's intuitive eye. There are some to-tomy shots sometimes (which could be called typical via master Ozu or other), but everything appears so precise on a first viewing, so descriptive. I think I almost can't go into all of them without a repeat viewing, but there were two that are still fresh in me. The first was right as Watanabe was about to sing in the bar, and there were these bead-strings looming in front of the camera. Perhaps mysterious, but definitely evocative.

The other was when Watanabe and one of the other clerks are on a bridge during a dark part of the day. Both characters are in silhouette, and Watanabe gives an indication to the character that he will die soon. But for me, I wasn't even paying a terrible amount of attention to the words. The way the two are lit as they are, with the light in the background and darkness in the foreground, it could maybe give an indication of what Kurosawa's trying to say: we're all not in the light of life, but it doesn't have to be an entire down-ward spiral if the will is good. Whether you're into philosophy (ies) or not, Ikiru won't disappoint newcomers to Kurosawa via his action pictures. A+

The old man Kanji Watanabe (in a wholly believable and often heart-breaking performance by Takashi Shimura) knows his life hasn't amounted to much as a (chief) clerk for the city. He knows he hasn't had a great kinship with his son. He's accepting his fate with a heavy soul. One of the tenets of existentialism is that there's free-will, and the responsibility to accept what is done with one's life. Kurosawa might've (as I speculate, I don't entirely know) caught onto this for his lead, and it works, especially with the little details.

Such little details, unforgettable ones, have been expounded upon by other reviewers and critics, such as the drunken, sullen singing of "Life is short, fall in love my maiden" in the bar. A scene like that almost speaks for itself and yet it's also subtle. But one scene that had me was one not too many talk about. It's when Watanabe is in the Deputy Mayor's office, asking for permission so that a park can be built. At first the Mayor ignores him, but then Watanabe begs, but not in a way that manipulates the audience for sympathy with the old man. The mayor must be sensing something in his eyes, desperate and weak, however determined, and it's something that probably most of the audience can identify with as well, even if they don't entirely identify with the character.

But aside from the emotional impact Ikiru can have on a viewer, composition-wise (with the help of Asakazu Nakai, wonderful cinematographer on less than a dozen Kurosawa films) and editing-wise the film is ahead of its time and another example of Kurosawa's intuitive eye. There are some to-tomy shots sometimes (which could be called typical via master Ozu or other), but everything appears so precise on a first viewing, so descriptive. I think I almost can't go into all of them without a repeat viewing, but there were two that are still fresh in me. The first was right as Watanabe was about to sing in the bar, and there were these bead-strings looming in front of the camera. Perhaps mysterious, but definitely evocative.

The other was when Watanabe and one of the other clerks are on a bridge during a dark part of the day. Both characters are in silhouette, and Watanabe gives an indication to the character that he will die soon. But for me, I wasn't even paying a terrible amount of attention to the words. The way the two are lit as they are, with the light in the background and darkness in the foreground, it could maybe give an indication of what Kurosawa's trying to say: we're all not in the light of life, but it doesn't have to be an entire down-ward spiral if the will is good. Whether you're into philosophy (ies) or not, Ikiru won't disappoint newcomers to Kurosawa via his action pictures. A+

I can safely say that I have seen no finer film than Kurosawa's true masterpiece, Ikiru. The story of a dying petty bureaucrat in 1950's Japan, Ikiru is as uncompromisingly honest and beautiful a film as has ever been made on the subject of life. Kurosawa elevates a story that could have been simple melodrama to the level of masterwork with a genuine love of his characters, and with an incredible technical direction. The film's structure accentuates and deepens its many, many lessons on life, and the performances, including a heartbreakingly earnest turn by Shimura are all flawless.

In short, Ikiru is easily one of the greatest works committed to film, and no discerning film aficionado should avoid experiencing it. Had Kurosawa directed only this film, it would still be enough to include him in the pantheon of the greatest storytellers who ever lived. Fortunately for us, it is simply the pinnacle of a staggeringly amazing career. It is the absolute definition of a 10/10 film.

In short, Ikiru is easily one of the greatest works committed to film, and no discerning film aficionado should avoid experiencing it. Had Kurosawa directed only this film, it would still be enough to include him in the pantheon of the greatest storytellers who ever lived. Fortunately for us, it is simply the pinnacle of a staggeringly amazing career. It is the absolute definition of a 10/10 film.

Ikiru is a film about life. Constantly complex and thought-provoking, although simple at the same time; it tells a story about life's limits, how we perceive life and the fact that life is short and not to be wasted. Our hero is Kanji Watanabe, the most unlikely 'hero' of all time. He works in a dreary city office, where nothing happens and it's all very meaningless. Watanabe is particularly boring, which has lead to him being nicknamed 'The Mummy' by a fellow worker. He later learns that he is dying from stomach cancer and that he only has six months to live. But Watanabe has been dead for thirty years, and now that he's learned that his life has a limit; it's time for Watanabe to escape his dreary life and finally start living. What follows is probably the most thoughtful analysis of life ever filmed.

Ikiru marks a departure for Akira Kurosawa, a man better known for his samurai films, but it's a welcome departure in my opinion. Kurosawa constantly refers to Watanabe as 'our hero' throughout the film, and at first this struck me as rather odd because, as I've mentioned, he's probably the least likely hero that Kurosawa has ever directed; but that's just it! This man is not a superhero samurai, but rather an ordinary guy that decides he doesn't want to be useless anymore. That's why he's 'our hero'. Kurosawa makes us feel for the character every moment he's on screen - we're sorry that he's wasted his life, and we're sorry that his wasted life is about to be cruelly cut short. However, despite the bleak and miserable facade that this movie gives out, there is a distinct beauty about it that shines through. The beauty emits from the way that Watanabe tries to redeem his life; because we feel for him and are with him every step of the way, it's easy to see why Watanabe acts in the way he does. Ikiru is a psychologically beautiful film.

It could be said that the fantastic first hour and a half is let down by a more politically based final third - and this is true. The movie needs it's final third in order to finish telling the story, but it really doesn't work as well as the earlier parts did. However, Kurosawa still delights us with some brilliant imagery and the shot of Watanabe on a swing is the most poetically brilliant thing that Kurosawa ever filmed. Together with the music and the rest of the film that you've seen so far; that picture that Kurosawa gives us is as moving as it is brilliant.

Ikiru marks a departure for Akira Kurosawa, a man better known for his samurai films, but it's a welcome departure in my opinion. Kurosawa constantly refers to Watanabe as 'our hero' throughout the film, and at first this struck me as rather odd because, as I've mentioned, he's probably the least likely hero that Kurosawa has ever directed; but that's just it! This man is not a superhero samurai, but rather an ordinary guy that decides he doesn't want to be useless anymore. That's why he's 'our hero'. Kurosawa makes us feel for the character every moment he's on screen - we're sorry that he's wasted his life, and we're sorry that his wasted life is about to be cruelly cut short. However, despite the bleak and miserable facade that this movie gives out, there is a distinct beauty about it that shines through. The beauty emits from the way that Watanabe tries to redeem his life; because we feel for him and are with him every step of the way, it's easy to see why Watanabe acts in the way he does. Ikiru is a psychologically beautiful film.

It could be said that the fantastic first hour and a half is let down by a more politically based final third - and this is true. The movie needs it's final third in order to finish telling the story, but it really doesn't work as well as the earlier parts did. However, Kurosawa still delights us with some brilliant imagery and the shot of Watanabe on a swing is the most poetically brilliant thing that Kurosawa ever filmed. Together with the music and the rest of the film that you've seen so far; that picture that Kurosawa gives us is as moving as it is brilliant.

"Ikiru" is supposedly one of Steven Spielberg's favourite films, and one can see the influence it's had on him not only in the sentimentality and the ultimate "feelgood factor" (which may be a little too extreme for some viewers, although the script never condescends), but visually, especially in the virtuoso sequence in which a reprobate leads our hero, a respectable and dull civil servant, on a whirlwind tour of Tokyo's frenzied nightlife - a masterpiece of camera placement and editing. With images throughout that will stay with you for a long time, and a terrific supporting performance by Miki Odagiri as a vivacious young "office lady", "Ikiru" is still an absolute knockout more than 50 years on.

This film touched me in a way no other film has. Filmed in black and white and gorgeous, both in the visuals and in how the story unfolds. Behold the clever manner of gradually unfolding the story as people jog each other's memories at his funeral (an obligation for them, that gradually turns into a real eulogy). Everything is told in flashbacks: the mourners' memories unfold naturally, as people remember what the man did and struggle to comprehend why.

This film I would nominate for the golden five of the century!

I first saw it in 1956 or so at a small theater in downtown Chicago. A second viewing, years later, confirmed my initial pleasure!

This film I would nominate for the golden five of the century!

I first saw it in 1956 or so at a small theater in downtown Chicago. A second viewing, years later, confirmed my initial pleasure!

Lo sapevi?

- QuizWhen Takashi Shimura rehearsed his singing of "Song of the Gondola," director Akira Kurosawa instructed him to "sing the song as if you are a stranger in a world where nobody believes you exist."

- BlooperWhen Kanji and the Novelist go to a busy, loud nightclub, the film has been reversed as evidenced by the backwards "Nippon Beer" banner in the background.

- ConnessioniFeatured in The Siskel & Ebert 500th Anniversary Special (1989)

- Colonne sonoreJ'ai Deux Amours

(uncredited)

Music by Vincent Scotto

Lyrics by Georges Koger and Henri Varna

Performed by Josephine Baker

[Played when entering the bar with the long-faced man]

I più visti

Accedi per valutare e creare un elenco di titoli salvati per ottenere consigli personalizzati

Dettagli

Botteghino

- Lordo Stati Uniti e Canada

- 60.239 USD

- Fine settimana di apertura Stati Uniti e Canada

- 2149 USD

- 29 dic 2002

- Lordo in tutto il mondo

- 114.026 USD

- Tempo di esecuzione

- 2h 23min(143 min)

- Colore

- Mix di suoni

- Proporzioni

- 1.37 : 1

Contribuisci a questa pagina

Suggerisci una modifica o aggiungi i contenuti mancanti

![Guarda Trailer [OV]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/M/MV5BMTg4OWJkNjMtM2Y0Mi00MzQ5LTk3Y2YtZWMwNGUyOTIyNGVjXkEyXkFqcGdeQXRyYW5zY29kZS13b3JrZmxvdw@@._V1_QL75_UX500_CR0)