VALUTAZIONE IMDb

7,2/10

7802

LA TUA VALUTAZIONE

Uno dei più grandi esperimenti del cinema, il film è un sforzo per catturare l'ossessione del poeta, combattuto tra le forze della vita e quelle della morte.Uno dei più grandi esperimenti del cinema, il film è un sforzo per catturare l'ossessione del poeta, combattuto tra le forze della vita e quelle della morte.Uno dei più grandi esperimenti del cinema, il film è un sforzo per catturare l'ossessione del poeta, combattuto tra le forze della vita e quelle della morte.

- Regia

- Sceneggiatura

- Star

- Premi

- 1 vittoria in totale

Recensioni in evidenza

A magical little movie that, as another reviewer so well put it, 'means itself'. the imaginatively tame and purely cerebral, of course, shouldn't touch it. i don't much like cocteau's literary work and find it on the whole to be labored, monotonous, pretentious and boring. his verbal 'surrealism' never seemed to me to be worthy of the name, it just seemed like incomprehensible,almost annoyingly sarcastic jargon that made my eyes water. (like some of beckett's stuff.) but cinematically, i can't deny that he could pull it off--and how. i may not be a fan, but i recognize visual surreality when i see it, being an avowed surrealism addict. this one ranks up there with some of bunuel and bergman's stuff in terms of its sheer fascination and genuine merit, and as soon as i finished watching it i watched it again almost immediately. i repeat, don't even bothering trying to interpret it intellectually or rationally, and this applies to surrealist film as a whole. it appeals to the unconscious mind and the imagination, not to reason. (david lynch is the jean cocteau of our time!) A must.

This film could very well have been made in collaboration with Luis Bunuel (Un Chien Andalou '29, L'Age D'Or '30), but it is less experimental and I don't think Cocteau takes full advantage of the screen time: the pace is low and there are no really shocking elements. I have to admit it could be a little shorter (despite it's only 60 minutes). That's not because Cocteau really needs much time, but because it's just slow. But then again, aren't most of his films and does it matter? The cinematography in by Georges Perinal (Le Million, The Fallen Idol) and the music sufficiently contribute to the fabulous imagery. See this film.

There is a similar snowball-throwing scene in this film which was used also in 'Les Enfants Terrible' (Melville, 1950) which was also written by Cocteau as you can see from the title sequence, and was created by Jean-Pierre Melville (Le Samourai, Un Flic) with the famous Cocteau-atmosphere.

10 points out of 10 :-)

There is a similar snowball-throwing scene in this film which was used also in 'Les Enfants Terrible' (Melville, 1950) which was also written by Cocteau as you can see from the title sequence, and was created by Jean-Pierre Melville (Le Samourai, Un Flic) with the famous Cocteau-atmosphere.

10 points out of 10 :-)

Jean Cocteau's first film subject- Blood of a Poet (episodes 1-4), all takes place between a second's worth of measurement in time. A chimney falls to the ground in a scene of pure demolishment, and for the more mysterious glimpses in the film we see them happening in a second's flash as well (if you blink you'll miss it).

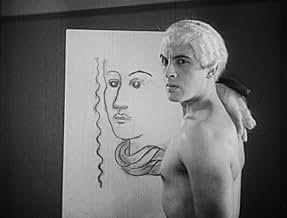

Before I saw Blood of a Poet, I figured it would be a debut Cocteau attempting a Bunuel type of filmic showcase of a different, though somewhat simple story with anarchic, subversively funny dream shots of a purely surreal nature. Then, there is the first shot, the opening image of the man, the introducer, like a ghost or a character in a Greek tragedy. The first episode is "Wounded Hand of the Scars of the Poet". Right from the music a viewer can realize Cocteau's picture is apart from Bunuel's achievement(s). The latter has a technique of classical music (Wagner over a scene of imposed seduction, for example) while Cocteau has the music as inviting, jubilant, even, however all the wigged man is doing is painting a face. It's almost like a cartoon, and for a fleeting instant, the face on the painting has lips that move. This is more than the usual surrealistic stoke of the brush- this is the first sign in motion picture history of an artist (i.e. painter) converting ideas into an episodic format. The purpose is the same- abstract thinking- but the format is of a different mind-set.

That's the first episode, that gets the viewer in, as another wigged man enters- sort of shocked- and exits like the wind. A wire face spins and the lips moving again like the painting he created just before. It could be the illusion of a lifetime, or a trick of the white light seeping out of the crevices in the lips in his hand, but the man, like us, can't ignore it until it is no more. That Cocteau has an intended poetic voice here in his brand of surrealism is a bonus of sorts to the intellectual type of audience member. And, it's not a downer to those who might not be interested in a filmmaker's ego- the artistry overcomes the ego, for the most-part anyway.

The second episode is titled "Do Walls Have Ears?", when the artist gets rid of the mouth, but now the man, the artist, is trapped in the room with the statue as the guardian. This is the first sign of the instantly narcissistic mood of Cocteau in the statue, a director in and of itself delivering enigmatic, haunting statement the mirror, again, shows with narcissism- the necessary narcissism, the kind to know one's self AND how he falls within himself like water. As the artist goes through the abyss, he winds up at the hotel (right in-between this Cocteau throws in a cut-away of a man disappearing after appearing for a number of seconds, creepy in its non-sense). Then, the artist views an execution through a key-hole in a door.

(Oh, did I mention that some of the dialog is quite possibly backwards- otherwise, what else could be the explanation of the point of it, except for random gibberish?)

Themes of suicide come up, then, soon enough after, the artist tires of this to the point of him leaving, climbing on the walls. At the end of this totally hypnotic two-parter, we see the reason, at the last for a clear instant, his emotion is now purely terror (by breaking the mirror, Cocteau tries to break through his own narcissistic tendencies).

The 3rd and 4th episodes are another kind of two-parter, and they center on a snowball fight and a card game, respectively. "The snowball fight" is entirely representative of the (true) brutal, near-primitiveness of the realities that go with childhood, leading up to a battered snowball victim at the side of an elegant man and woman dealing a game with each other. Suddenly, during this ("The Profanation of the Host" as it's appropriately titles) surrealism is at an astonishing height for its time. One shot, in particular, seemed to be an inspiration for a part of the Jupiter landing in 2001. A card is lifted from the boy, an assist in the game, and the man ends up losing, the boy (and the black man) revealing disgust in the elegance of the situation of the game.

That's when it hit me, the message of Blood of a Poet. Behind beauty, as well as behind one's own desires and vision, even if we can't entirely explain why it's beautiful or why we hold these desires for ourselves is the darkness that beckons (perhaps in the slightest of moments of our lives) in our deepest, most assuredly dream-like delusions of grandeur. From this, you could gather, Blood of a Poet seems like it may not be for everyone, certainly not for those who can't even remember one dream from their entire life (personally I thought it contained inklings of pretentious gobledy-gook). But its nature is something to look for, and if you only see the movie once, you might not be sorry. Grade: A

Before I saw Blood of a Poet, I figured it would be a debut Cocteau attempting a Bunuel type of filmic showcase of a different, though somewhat simple story with anarchic, subversively funny dream shots of a purely surreal nature. Then, there is the first shot, the opening image of the man, the introducer, like a ghost or a character in a Greek tragedy. The first episode is "Wounded Hand of the Scars of the Poet". Right from the music a viewer can realize Cocteau's picture is apart from Bunuel's achievement(s). The latter has a technique of classical music (Wagner over a scene of imposed seduction, for example) while Cocteau has the music as inviting, jubilant, even, however all the wigged man is doing is painting a face. It's almost like a cartoon, and for a fleeting instant, the face on the painting has lips that move. This is more than the usual surrealistic stoke of the brush- this is the first sign in motion picture history of an artist (i.e. painter) converting ideas into an episodic format. The purpose is the same- abstract thinking- but the format is of a different mind-set.

That's the first episode, that gets the viewer in, as another wigged man enters- sort of shocked- and exits like the wind. A wire face spins and the lips moving again like the painting he created just before. It could be the illusion of a lifetime, or a trick of the white light seeping out of the crevices in the lips in his hand, but the man, like us, can't ignore it until it is no more. That Cocteau has an intended poetic voice here in his brand of surrealism is a bonus of sorts to the intellectual type of audience member. And, it's not a downer to those who might not be interested in a filmmaker's ego- the artistry overcomes the ego, for the most-part anyway.

The second episode is titled "Do Walls Have Ears?", when the artist gets rid of the mouth, but now the man, the artist, is trapped in the room with the statue as the guardian. This is the first sign of the instantly narcissistic mood of Cocteau in the statue, a director in and of itself delivering enigmatic, haunting statement the mirror, again, shows with narcissism- the necessary narcissism, the kind to know one's self AND how he falls within himself like water. As the artist goes through the abyss, he winds up at the hotel (right in-between this Cocteau throws in a cut-away of a man disappearing after appearing for a number of seconds, creepy in its non-sense). Then, the artist views an execution through a key-hole in a door.

(Oh, did I mention that some of the dialog is quite possibly backwards- otherwise, what else could be the explanation of the point of it, except for random gibberish?)

Themes of suicide come up, then, soon enough after, the artist tires of this to the point of him leaving, climbing on the walls. At the end of this totally hypnotic two-parter, we see the reason, at the last for a clear instant, his emotion is now purely terror (by breaking the mirror, Cocteau tries to break through his own narcissistic tendencies).

The 3rd and 4th episodes are another kind of two-parter, and they center on a snowball fight and a card game, respectively. "The snowball fight" is entirely representative of the (true) brutal, near-primitiveness of the realities that go with childhood, leading up to a battered snowball victim at the side of an elegant man and woman dealing a game with each other. Suddenly, during this ("The Profanation of the Host" as it's appropriately titles) surrealism is at an astonishing height for its time. One shot, in particular, seemed to be an inspiration for a part of the Jupiter landing in 2001. A card is lifted from the boy, an assist in the game, and the man ends up losing, the boy (and the black man) revealing disgust in the elegance of the situation of the game.

That's when it hit me, the message of Blood of a Poet. Behind beauty, as well as behind one's own desires and vision, even if we can't entirely explain why it's beautiful or why we hold these desires for ourselves is the darkness that beckons (perhaps in the slightest of moments of our lives) in our deepest, most assuredly dream-like delusions of grandeur. From this, you could gather, Blood of a Poet seems like it may not be for everyone, certainly not for those who can't even remember one dream from their entire life (personally I thought it contained inklings of pretentious gobledy-gook). But its nature is something to look for, and if you only see the movie once, you might not be sorry. Grade: A

The Surrealist movement, as an artistic revolution has been utterly dominated by the name Salvador Dali at least in popular culture. Those in the know may be able to list a few other artists such as Roberto Matta or Max Ernst; perhaps make a tentative connection between Surrealism and Cubism and by extension Pablo Picasso. Even fewer people realize Surrealism has left an indelible impact on film which still seeps into the unconscious of many a-movie. Luis Bunuel's Un Chien Andalou (1929) stands as one obvious example but while Bunuel's career is infamous within cinema circles, many people don't consider French director, writer, and all around renaissance man Jean Cocteau to be part of the movement.

The Blood of a Poet is the first part of Jean Cocteau's Orpheus Trilogy (1932-1960); a loosely connected telling and re-telling of the well-known Greek legend. In this installment, our poet (Rivero) stands in a studio, painting on a canvas with the intensity seen in the most obsessive of human beings. His creations start to come to life, first the paintings then the sculptures. As he discovers the dreamlike dimensions of the room and it's contents, the poet goes into a fugue state falling through mirrors and peering through keyholes. The film ends with the destruction of a factory-type tower or smokestack precipitated by the constant appearance of a muse like figure. By the end she's lying in darkness with a lyre and a globe symbolizing Erato the muse of lyric poetry or maybe Urania the muse of astronomy.

Jean Cocteau is arguably most known for his poetry though he's dabbled in theatre, novel writing and of course film. In the realm of cinema his crowning accomplishment is The Beauty and the Beast (1946) which showed remarkable economy in storytelling and in special-effects. The Blood of a Poet however is a 55 minute concentrated dose of Cocteau at his most creative. Few films today can catapult it's audience into the outer limits of cinematic artistry and with today's spreadsheet, bottom-line obsessed studios there is simply no room for experimentation. Yet in 1930, one man was seemingly given unlimited resources to play with the form and unlike Bunuel's aforementioned Un Chien Andalou and L'Age d'Or (1930), Cocteau's oeuvre concentrates on the sublime not on the grotesque. Interesting to note that Cocteau had been dubbed by his contemporaries "The Frivolous Prince," for his bohemian lifestyle and romantic view of poetry. It certainly shows here.

Those who lived prior to the films release accused it of being anti- religious and delayed its release by two years. Modern skeptics complain that the film is incredibly pretentious and others still, express it is aggressively political in nature. They're not wrong; all the above can be true and false depending on your attitude and disposition. If you're one to take artist intent into consideration Cocteau wrote an essay on The Blood of a Poet contending that it is not a surreal film at all! But rather an attempt to "...avoid the deliberate manifestations of the unconscious in favor of a kind of half-sleep through which I wandered as though in a labyrinth." As with all surreal artwork, the film is ultimately an exercise in personal interpretation.

What remains certain is The Blood of a Poet packs more themes, more story, more experimentation and more beauty in it's scant screen- time than most TV-series' put into their entire run. The ingenuity and raw emotional power embedded in this film is stunning and are sure to bedevil you in your daydreams and in your sleep. I truly, in my heart of hearts believe The Blood of a Poet to be the ideal first film for those wishing to delve into Surrealism. Of course that's just my interpretation; I suppose that's the point.

The Blood of a Poet is the first part of Jean Cocteau's Orpheus Trilogy (1932-1960); a loosely connected telling and re-telling of the well-known Greek legend. In this installment, our poet (Rivero) stands in a studio, painting on a canvas with the intensity seen in the most obsessive of human beings. His creations start to come to life, first the paintings then the sculptures. As he discovers the dreamlike dimensions of the room and it's contents, the poet goes into a fugue state falling through mirrors and peering through keyholes. The film ends with the destruction of a factory-type tower or smokestack precipitated by the constant appearance of a muse like figure. By the end she's lying in darkness with a lyre and a globe symbolizing Erato the muse of lyric poetry or maybe Urania the muse of astronomy.

Jean Cocteau is arguably most known for his poetry though he's dabbled in theatre, novel writing and of course film. In the realm of cinema his crowning accomplishment is The Beauty and the Beast (1946) which showed remarkable economy in storytelling and in special-effects. The Blood of a Poet however is a 55 minute concentrated dose of Cocteau at his most creative. Few films today can catapult it's audience into the outer limits of cinematic artistry and with today's spreadsheet, bottom-line obsessed studios there is simply no room for experimentation. Yet in 1930, one man was seemingly given unlimited resources to play with the form and unlike Bunuel's aforementioned Un Chien Andalou and L'Age d'Or (1930), Cocteau's oeuvre concentrates on the sublime not on the grotesque. Interesting to note that Cocteau had been dubbed by his contemporaries "The Frivolous Prince," for his bohemian lifestyle and romantic view of poetry. It certainly shows here.

Those who lived prior to the films release accused it of being anti- religious and delayed its release by two years. Modern skeptics complain that the film is incredibly pretentious and others still, express it is aggressively political in nature. They're not wrong; all the above can be true and false depending on your attitude and disposition. If you're one to take artist intent into consideration Cocteau wrote an essay on The Blood of a Poet contending that it is not a surreal film at all! But rather an attempt to "...avoid the deliberate manifestations of the unconscious in favor of a kind of half-sleep through which I wandered as though in a labyrinth." As with all surreal artwork, the film is ultimately an exercise in personal interpretation.

What remains certain is The Blood of a Poet packs more themes, more story, more experimentation and more beauty in it's scant screen- time than most TV-series' put into their entire run. The ingenuity and raw emotional power embedded in this film is stunning and are sure to bedevil you in your daydreams and in your sleep. I truly, in my heart of hearts believe The Blood of a Poet to be the ideal first film for those wishing to delve into Surrealism. Of course that's just my interpretation; I suppose that's the point.

Cocteau's first feature certainly reflects the early idealism of cinema, that "we can do it!" spirit that made early artists truly believe in the potential of cinema as a medium to trump all other arts. Thematically similar to the more famous surrealist work "Un chien Andalou," "Le sang d'un poete" is a chroma-key free-for all, with talking hands, statues that come to life, and banal bourgeoise cardgames transpiring on children's corpses. It's hard to watch at times, made even harder by what I think is a terribly distracting score (to the point where I just turned the sound off and enjoyed the film as a silent with subtitles.) However, by the end one realises Cocteau's heartfelt audacity, and the true spirit of the early cinema artists who wanted to do things with film that nobody has the cojones to try today.

A seminal work in experimentalist cinema; why does it seem like we've fallen way behind?

A seminal work in experimentalist cinema; why does it seem like we've fallen way behind?

Lo sapevi?

- QuizBecause of the October 1930 scandal around Luis Buñuel's L'Âge d'or (1930) - another film financed by Le Vicomte de Noailles and Marie-Laure de Noailles, the Paris premiere of this film was delayed until January 1932.

- ConnessioniFeatured in Jean Cocteau: Autoportrait d'un inconnu (1983)

I più visti

Accedi per valutare e creare un elenco di titoli salvati per ottenere consigli personalizzati

- How long is The Blood of a Poet?Powered by Alexa

Dettagli

- Data di uscita

- Paese di origine

- Lingue

- Celebre anche come

- The Blood of a Poet

- Azienda produttrice

- Vedi altri crediti dell’azienda su IMDbPro

- Tempo di esecuzione

- 55min

- Colore

- Proporzioni

- 1.37 : 1

Contribuisci a questa pagina

Suggerisci una modifica o aggiungi i contenuti mancanti