VALUTAZIONE IMDb

6,7/10

2146

LA TUA VALUTAZIONE

Aggiungi una trama nella tua linguaA sharecropper decides to become a preacher after falling for a vamp from the city.A sharecropper decides to become a preacher after falling for a vamp from the city.A sharecropper decides to become a preacher after falling for a vamp from the city.

- Regia

- Sceneggiatura

- Star

- Candidato a 1 Oscar

- 3 vittorie e 1 candidatura in totale

Matthew 'Stymie' Beard

- Child

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

Evelyn Pope Burwell

- Singer

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

Eddie Conners

- Singer

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

William Allen Garrison

- Heavy

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

Eva Jessye

- Singer

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

Sam McDaniel

- Adam

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

Clarence Muse

- Church Member

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

Recensioni in evidenza

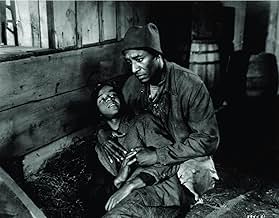

A film that has a lot to unpack, and a lot to consider. It was made with an all-black cast by director King Vidor with what I believe were good intentions, has some fantastic performances, and tells a good story, but it touches a nerve with its stereotypes. What was liberal in 1929 is known to be backwards today, and this is what makes it such a complicated film. I enjoyed it for its positives and would suggest viewers not dismiss the film entirely, but I'll start with acknowledging the problematic parts, at least the way I see them, FWIW.

As African-American intellectuals like Lorraine Hansberry, James Baldwin, and others explained it so well in the late 1950's, one of the mechanisms white Americans used to cope with the outrageous horror of slavery after it ended was to continue thinking of blacks as somehow different than human. An outright racist considered them lesser, inferior beings. Well-intentioned liberals often embraced the idea that they were a simple, rhythmical people, steeped in Christianity, and possessing a deep wellspring of forgiveness. This reduced the collective guilt over a horror which simply could not be faced, and which to this day has not been reconciled. The liberal view of the day, what we see manifested in this film, is of course preferable to what we might see from someone like D.W. Griffith, but either characterization is dangerous, and robs African-Americans of their humanity.

In the film, the characters are way too happy being poor and picking cotton. I mean, it's better than 'Gone with the Wind', where they're happy to be the slaves of masters who are portrayed as benevolent and genteel, but it still falls into the trap of thinking of them as just simple folk who like to dance after a long day in the field. See, they're all free and happy now, slavery is over, and we certainly don't need to think about some form of reparations for our part in 300+ years of slavery and the death of upwards of 100 million Africans. The film is trying to give its mostly white audience a window into African-American life, similar to how the 'expedition' films from the period presented Polynesians, Inuits, etc ... many of which were made with cultural condescension, and it's telling that there are no white characters, discriminating against them or terrorizing them, as if they were in their own little bubble, or on an island somewhere. And unfortunately, coming along with the singing, dancing, and revival preaching are stereotypes. One of the worst is in the way the main character (Daniel L. Haynes) simply cannot control himself around women, and one (Nina Mae McKinney) in particular. Even though we may see some of that in white individuals from other films (Lionel Barrymore as a preacher in 'Sadie Thompson' from 1928 comes to mind), here it's associated with such a negative stereotype, the sexual aggressiveness of black men, and amplified by Haynes's eyes twitching in tight shots.

On the other hand, I think we have to give the film and Vidor some credit too. To make his first sound picture with an all-black cast is impressive. The main story line could have been based on white characters, and we see a range of human emotion and folly. The musical performances and the dancing from the main characters and various others are excellent. Daniel L. Haynes has quite a presence, and his deep voice and preaching style might just convert you if you're not careful. I loved his imitating a train chugging down the tracks in one of his sermons. Nina Mae McKinney is a revelation too - so well-cast, conveying depravity, wildness, deceit, and contrition all very well. It's all the more impressive considering she was just 17 years old when the film came out, and 16 when it was filmed. The acting is a little uneven, consistent for the period, but one thing I noticed was that the performances are uniformly less reserved and restrained, and that along with pretty damn good sound quality results in more energy and vibrancy on the screen - especially as it compares to other early talkies in 1929 and 1930, many of which are incredibly creaky and brittle. I had a little bit of the same feeling I had about 'Stormy Weather' (1943), another film containing stereotypes, that the performances transcended the narrow framework they were placed in.

Because of all of the concerns about race, I think some of Vidor's great shots in the film get overlooked. He shows us the cotton ginning process, and Haynes up on a huge lumber saw cutting long boards from a tree. He gives a shot of a fantastic drummer in a ragtime band, throwing and catching his sticks as he plays. He shows us the orgiastic gyrations of a wild church scene with excellent camera work, and gives us a chase through a swamp that was likely influential to other filmmakers. Lastly, while McKinney's character falls into the age-old (and misogynistic) temptress type, we also see that she can take care of herself, in one scene beating the hell out of a guy with a fireplace poker after he tries to force himself on her, which despite the violence was frankly great to see.

The bottom line though ... was this film a step forward? That's hard for me to answer. It's worth seeing and the dialog which probes a little deeper than the extreme positions (e.g. distilling it down to "old-timey racism" or "what's the problem, there's no racism here") is worthwhile. If you want to get a better window into the African-American experience from this period, however, you should check out 'Within Our Gates' (1920) by director Oscar Micheaux.

As African-American intellectuals like Lorraine Hansberry, James Baldwin, and others explained it so well in the late 1950's, one of the mechanisms white Americans used to cope with the outrageous horror of slavery after it ended was to continue thinking of blacks as somehow different than human. An outright racist considered them lesser, inferior beings. Well-intentioned liberals often embraced the idea that they were a simple, rhythmical people, steeped in Christianity, and possessing a deep wellspring of forgiveness. This reduced the collective guilt over a horror which simply could not be faced, and which to this day has not been reconciled. The liberal view of the day, what we see manifested in this film, is of course preferable to what we might see from someone like D.W. Griffith, but either characterization is dangerous, and robs African-Americans of their humanity.

In the film, the characters are way too happy being poor and picking cotton. I mean, it's better than 'Gone with the Wind', where they're happy to be the slaves of masters who are portrayed as benevolent and genteel, but it still falls into the trap of thinking of them as just simple folk who like to dance after a long day in the field. See, they're all free and happy now, slavery is over, and we certainly don't need to think about some form of reparations for our part in 300+ years of slavery and the death of upwards of 100 million Africans. The film is trying to give its mostly white audience a window into African-American life, similar to how the 'expedition' films from the period presented Polynesians, Inuits, etc ... many of which were made with cultural condescension, and it's telling that there are no white characters, discriminating against them or terrorizing them, as if they were in their own little bubble, or on an island somewhere. And unfortunately, coming along with the singing, dancing, and revival preaching are stereotypes. One of the worst is in the way the main character (Daniel L. Haynes) simply cannot control himself around women, and one (Nina Mae McKinney) in particular. Even though we may see some of that in white individuals from other films (Lionel Barrymore as a preacher in 'Sadie Thompson' from 1928 comes to mind), here it's associated with such a negative stereotype, the sexual aggressiveness of black men, and amplified by Haynes's eyes twitching in tight shots.

On the other hand, I think we have to give the film and Vidor some credit too. To make his first sound picture with an all-black cast is impressive. The main story line could have been based on white characters, and we see a range of human emotion and folly. The musical performances and the dancing from the main characters and various others are excellent. Daniel L. Haynes has quite a presence, and his deep voice and preaching style might just convert you if you're not careful. I loved his imitating a train chugging down the tracks in one of his sermons. Nina Mae McKinney is a revelation too - so well-cast, conveying depravity, wildness, deceit, and contrition all very well. It's all the more impressive considering she was just 17 years old when the film came out, and 16 when it was filmed. The acting is a little uneven, consistent for the period, but one thing I noticed was that the performances are uniformly less reserved and restrained, and that along with pretty damn good sound quality results in more energy and vibrancy on the screen - especially as it compares to other early talkies in 1929 and 1930, many of which are incredibly creaky and brittle. I had a little bit of the same feeling I had about 'Stormy Weather' (1943), another film containing stereotypes, that the performances transcended the narrow framework they were placed in.

Because of all of the concerns about race, I think some of Vidor's great shots in the film get overlooked. He shows us the cotton ginning process, and Haynes up on a huge lumber saw cutting long boards from a tree. He gives a shot of a fantastic drummer in a ragtime band, throwing and catching his sticks as he plays. He shows us the orgiastic gyrations of a wild church scene with excellent camera work, and gives us a chase through a swamp that was likely influential to other filmmakers. Lastly, while McKinney's character falls into the age-old (and misogynistic) temptress type, we also see that she can take care of herself, in one scene beating the hell out of a guy with a fireplace poker after he tries to force himself on her, which despite the violence was frankly great to see.

The bottom line though ... was this film a step forward? That's hard for me to answer. It's worth seeing and the dialog which probes a little deeper than the extreme positions (e.g. distilling it down to "old-timey racism" or "what's the problem, there's no racism here") is worthwhile. If you want to get a better window into the African-American experience from this period, however, you should check out 'Within Our Gates' (1920) by director Oscar Micheaux.

I probably don't need to go into the historical facts about this movie or the plot, as this had probably been expunded in numerous other comments. Personally I think that Hallelujah is a beautiful and powerful film, sympathetic to African Americans, and I think it's remarkable that it was produced at all.

Hallelujah is a huge production, with hundreds of extras. The cast was made up of mostly unknowns. Cast members like Fally Belle McKnight and Victoria Spivey apparently never made any other films, and leads Daniel L. Haynes and Nina Mae McKinney were obviously getting started. The cast is very good, I thought, especially Spivey (a veteran of the stage) as Rose. Haynes is okay in the beginning, seeming a little uneven in his role as well-meaning rogue Zeke, but the final scenes allow him to prove the commanding presence he could muster as an screen presence. Nina Mae McKinney is a power-house. A short, curvy beauty with an interesting voice, she has something of a young Myrna Loy. In fact, I just recently saw a still from a Loy film called The Squall where Loy looks an awful lot like McKinney.

Movies like Hallelujah are an acquired taste. When I first saw it, I was distracted by the crudeness of the sound, the jagged editing and the overall unevenness of the movie. Sure, two or three years later, Hollywood was turning out glossy productions like Red Dust and Blond Venus, with highly polished editing, clear sound and more mobile camera-work, but this is 1929. Sound film-making techniques had yet to be smoothed out. The crinkles of a young process actually add charm to this film, if you know to expect them.

I'll admit as well that, when I first saw Hallelujah, I was irritated by the voices. There's a lot of screeching from the women, and a great deal of mumbling as well. A second viewing, though, allows one to see past these "irritating" aspects and appreciate the voices for what they are. This way, Fanny Belle McKnight's agonized cries of sorrow and her singing the children to sleep is more touching than it is grating.

It's hard to know what else to say about the film. For all it's shortcomings, it's a touching film, lyrical even. I think it's a wonderful production, and I doubt it would not have been made much differently by a black director. Plus, one must agree, King Vidor was a far better craftsman than Oscar Micheaux. 9/10

Hallelujah is a huge production, with hundreds of extras. The cast was made up of mostly unknowns. Cast members like Fally Belle McKnight and Victoria Spivey apparently never made any other films, and leads Daniel L. Haynes and Nina Mae McKinney were obviously getting started. The cast is very good, I thought, especially Spivey (a veteran of the stage) as Rose. Haynes is okay in the beginning, seeming a little uneven in his role as well-meaning rogue Zeke, but the final scenes allow him to prove the commanding presence he could muster as an screen presence. Nina Mae McKinney is a power-house. A short, curvy beauty with an interesting voice, she has something of a young Myrna Loy. In fact, I just recently saw a still from a Loy film called The Squall where Loy looks an awful lot like McKinney.

Movies like Hallelujah are an acquired taste. When I first saw it, I was distracted by the crudeness of the sound, the jagged editing and the overall unevenness of the movie. Sure, two or three years later, Hollywood was turning out glossy productions like Red Dust and Blond Venus, with highly polished editing, clear sound and more mobile camera-work, but this is 1929. Sound film-making techniques had yet to be smoothed out. The crinkles of a young process actually add charm to this film, if you know to expect them.

I'll admit as well that, when I first saw Hallelujah, I was irritated by the voices. There's a lot of screeching from the women, and a great deal of mumbling as well. A second viewing, though, allows one to see past these "irritating" aspects and appreciate the voices for what they are. This way, Fanny Belle McKnight's agonized cries of sorrow and her singing the children to sleep is more touching than it is grating.

It's hard to know what else to say about the film. For all it's shortcomings, it's a touching film, lyrical even. I think it's a wonderful production, and I doubt it would not have been made much differently by a black director. Plus, one must agree, King Vidor was a far better craftsman than Oscar Micheaux. 9/10

There's something hypnotic about good preaching. All that passion, all that energy, whether it's in film or in person, has a cumulative power. It's hard to doubt the spreading power of religion when you see Daniel L. Haynes (this film) or Robert Duvall ("The Apostle"), or read the sermon at the end of "The Sound and the Fury." Feverishly, they try and communicate God's word. They rant, they rave, they speak quickly and with an undeniable amount of integrity. They get the crowd going, usually in whoops and outbursts, and one man's conversation with God becomes a community event. (Indeed, the power of a worked-up crowd is a powerful tool in and of itself).

That's what's so terrific about King Vidor's "Hallelujah." Everyone's up in arms about one thing or another in this movie, whether it's money, sex, or Jesus. Early in the film there's a rather ludicrous scene where the hero's brother is accidentally killed, due to the hero's folly and hubris. That's his Sin, for which he must Redeem Himself Before God. There's also a woman who represents Temptation, who leads him astray time and time again. In the end there's an extended chase through a swamp, that would be done again in Kurosawa's "Stray Dogs."

All of that's well and good, but the film really peaks during the sermon sequences. Done wrong, sermons in movies usually pass by unnoticed, or are used as a clothsline to hang lame jokes about apathetic churchgoers. Done right, as in this film, "The Apostle," and the most unusual ones in "Beloved," they can be as captivating as if you were really in attendance. It's a testament to the power of the motion picture.

That's what's so terrific about King Vidor's "Hallelujah." Everyone's up in arms about one thing or another in this movie, whether it's money, sex, or Jesus. Early in the film there's a rather ludicrous scene where the hero's brother is accidentally killed, due to the hero's folly and hubris. That's his Sin, for which he must Redeem Himself Before God. There's also a woman who represents Temptation, who leads him astray time and time again. In the end there's an extended chase through a swamp, that would be done again in Kurosawa's "Stray Dogs."

All of that's well and good, but the film really peaks during the sermon sequences. Done wrong, sermons in movies usually pass by unnoticed, or are used as a clothsline to hang lame jokes about apathetic churchgoers. Done right, as in this film, "The Apostle," and the most unusual ones in "Beloved," they can be as captivating as if you were really in attendance. It's a testament to the power of the motion picture.

In 1929, MGM began the process of converting to sound. They were almost the "latecomers" of sound conversion compared to their competitors over at the Warners lot; Warners' Vitaphone was pretty much in full swing by 1929 after having experimented with orchestral sound on film in 1926 in "The Better 'Ole" and "Don Juan" and then with actual voice embedment on film in "The Jazz Singer" the following year.

Even for such a major film studio like MGM, the cost was almost prohibitive, so Louis B. Mayer was skeptical about financing a major film epic featuring an all black cast. In the first half of the 20th Century, the major film studios catered mostly to white audiences, so a project of this nature was almost unheard of. Director, King Vidor was personally convinced that this film would be a success at the box office that he offered to match MGM dollar for dollar in producing this film. That said, the executives at MGM agreed, reluctantly, to take on this project.

I was totally surprised by the candidness of the material. From the way the major studios depicted black people as individuals of little or no importance, usually portraying them in a very negative way, I was at first skeptical. I expected more singing, dancing and stereotyping. Little did I know what a surprise I was in for! MGM could not have done a better job at portraying individuals with such humanistic qualities. As with most backdrops featuring blacks, it takes place in the cotton fields of the South; the motion picture industry failed miserably to depict black urban or middle class life until decades later.

Amazingly, most, if not all, of these actors were untested individuals on the screen or stage. Vidor's direction, along with these actors' willingness to succeed on the screen, created a work of art for the cinema. A huge box office success, "Hallelujah" was an oasis in an otherwise all-white world of big business cinema. It is a shame that the movie moguls at the time did not take further advantage of the acting talents of minorities.

Leonard Maltin could not have put it more succinctly when he said about Hallelujah: "King Vidor's early talkie triumph, a stylized view of black life focusing on a Southern cotton-picker who becomes a preacher but retains all-too-human weaknesses." Definitely a home run! A must see!

Even for such a major film studio like MGM, the cost was almost prohibitive, so Louis B. Mayer was skeptical about financing a major film epic featuring an all black cast. In the first half of the 20th Century, the major film studios catered mostly to white audiences, so a project of this nature was almost unheard of. Director, King Vidor was personally convinced that this film would be a success at the box office that he offered to match MGM dollar for dollar in producing this film. That said, the executives at MGM agreed, reluctantly, to take on this project.

I was totally surprised by the candidness of the material. From the way the major studios depicted black people as individuals of little or no importance, usually portraying them in a very negative way, I was at first skeptical. I expected more singing, dancing and stereotyping. Little did I know what a surprise I was in for! MGM could not have done a better job at portraying individuals with such humanistic qualities. As with most backdrops featuring blacks, it takes place in the cotton fields of the South; the motion picture industry failed miserably to depict black urban or middle class life until decades later.

Amazingly, most, if not all, of these actors were untested individuals on the screen or stage. Vidor's direction, along with these actors' willingness to succeed on the screen, created a work of art for the cinema. A huge box office success, "Hallelujah" was an oasis in an otherwise all-white world of big business cinema. It is a shame that the movie moguls at the time did not take further advantage of the acting talents of minorities.

Leonard Maltin could not have put it more succinctly when he said about Hallelujah: "King Vidor's early talkie triumph, a stylized view of black life focusing on a Southern cotton-picker who becomes a preacher but retains all-too-human weaknesses." Definitely a home run! A must see!

"Hallelujah" is a very interesting film. For that reason alone, it should be seen. It has an all-black cast and it was released in 1929, just as sound was first being used in films.

However, it is a very uneven production. We should give it some slack because of when it was produced, but not to mention its deficiencies would be dishonest. The acting, the lighting, the sound--all are uneven. Sometimes it is distracting, sometimes not.

Zeke (Daniel L. Haynes) is the central character. He lives with his large family, growing cotton. When the crop is harvested, he and his brother have it processed and baled. They deliver it to the riverboat and sell it on the dock. There in the city, with the money burning a hole in his pocket, he is introduced to some unscrupulous characters. He is naïve and obviously unaware of some basic rules of life and film: Never shoot with another man's dice. Never take a knife to a gunfight. And never, never go for a woman who gives her attentions to the highest bidder.

The story is filled with clichés and stereotypes, and it frequently drags. It has its compelling moments, like a chase through a swamp. But what bothers me most is the overly-dramatic acting. This is partly due to the fact that many of the scenes were couched in religious fervor. There are revival scenes, baptism scenes, scenes of general praying. In fact, the entire film is presented as a religious parable. Often when the characters speak, it is as if they are preaching. This interferes with the authenticity of the action, making some characters seem more caricatures than real people.

"Hallelujah" is a musical. Songs accent almost every scene. Most of them are gospel/spirituals. But the two best songs were written by Irving Berlin ("At The End of the Road" and "Swanee Shuffle").

However, it is a very uneven production. We should give it some slack because of when it was produced, but not to mention its deficiencies would be dishonest. The acting, the lighting, the sound--all are uneven. Sometimes it is distracting, sometimes not.

Zeke (Daniel L. Haynes) is the central character. He lives with his large family, growing cotton. When the crop is harvested, he and his brother have it processed and baled. They deliver it to the riverboat and sell it on the dock. There in the city, with the money burning a hole in his pocket, he is introduced to some unscrupulous characters. He is naïve and obviously unaware of some basic rules of life and film: Never shoot with another man's dice. Never take a knife to a gunfight. And never, never go for a woman who gives her attentions to the highest bidder.

The story is filled with clichés and stereotypes, and it frequently drags. It has its compelling moments, like a chase through a swamp. But what bothers me most is the overly-dramatic acting. This is partly due to the fact that many of the scenes were couched in religious fervor. There are revival scenes, baptism scenes, scenes of general praying. In fact, the entire film is presented as a religious parable. Often when the characters speak, it is as if they are preaching. This interferes with the authenticity of the action, making some characters seem more caricatures than real people.

"Hallelujah" is a musical. Songs accent almost every scene. Most of them are gospel/spirituals. But the two best songs were written by Irving Berlin ("At The End of the Road" and "Swanee Shuffle").

Lo sapevi?

- QuizAlthough this film is frequently touted as the first black-cast film produced in Hollywood, it is actually predated by the more obscure Hearts in Dixie (1929).

- BlooperWhen Zeke confronts Chick and Hot Shot and strong-arms them in front of the crowd, the shadow of the microphone falls across Hot Shot as he is pushed to the background of the scene and tries to regain his composure. The shadow of the boom is also visible falling across the extras behind him.

- Versioni alternativeMGM also issued this movie in a silent version, with Marian Ainslee writing the titles.

- Colonne sonoreSometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child

(uncredited)

Traditional Spiritual

Sung offscreen during the opening credits

I più visti

Accedi per valutare e creare un elenco di titoli salvati per ottenere consigli personalizzati

- How long is Hallelujah?Powered by Alexa

Dettagli

- Tempo di esecuzione1 ora 49 minuti

- Colore

- Proporzioni

- 1.20 : 1

Contribuisci a questa pagina

Suggerisci una modifica o aggiungi i contenuti mancanti