VALUTAZIONE IMDb

7,3/10

5012

LA TUA VALUTAZIONE

Un uomo ottiene un lavoro in un manicomio nella speranza di vedere sua moglie.Un uomo ottiene un lavoro in un manicomio nella speranza di vedere sua moglie.Un uomo ottiene un lavoro in un manicomio nella speranza di vedere sua moglie.

- Regia

- Sceneggiatura

- Star

Recensioni in evidenza

Kurutta Ippeji offers a view on the distorted perspective of a troubled janitor in a mental asylum. As a proof of concept, it shows that experimental cinematic techniques can affect the way narration is perceived by the viewer - here, the visual elements contribute to how the viewer experiences the characters' mental state. As an experiment, the movie possibly even makes a stronger case than the comparably surreal Hausu (1977), which is partly imbalanced in its style. However, due to the poor visual quality and the lack of functional storytelling, this experimental feature can't be easily recommended to people looking for a more conventional feature.

Overall 7/10

Full Review on movie-discouse.blogspot.com

This is actually one of the titles of the film, a page out of order. It perfectly reflects the film itself, a narrative fractured, demented, cast in and out of a feverish mind, but ultimately incomplete to us, and the various misconceptions it has spawned in trying to evaluate as though it was the whole thing.

I was increasingly suspicious of this while watching, that I was basically confronted with an incomplete film and so a film impenetrable not wholly by design but only because the keys have been lost to us, or are not attached to the film we are watching and we have to apprehend elsewhere. Doing a little research afterwards only confirmed my doubts. So a little context:

-the film is not the tip of the iceberg of an advanced cinema whose main body is lamentably lost to us; it was saved exactly because it was an exception, a low-budget oddity the filmmaker himself re-discovered in his garden shed. The majority of silent Japanese cinema - whose final traces were eclipsed in the aftermath of WWII - were generic studio reworkings of popular material.

-it is not the product of an 'isolated cinematic environment free of influence', rather a studied attempt to recreate what the French avant-garde was pioneering at the time; so yes, the superimpositions, the haze of motions and details, the rapid-fire montage, all of them tools in the attempt to offer us a glimpse of the fractured, elusive reality of the mind, available tools at the time that Kinugasa knew from other films.

-so even though the idea of a janitor coming to work in a mental hospital may carry hues of Caligari, the film itself is from the line of what in France was called impressionism; the films of Epstein, L'Herbier, Gance.

-most importantly, even though the closest parable I can think of is Menilmontant, another French film from the same year that in place of story tried to paint with only images a state of mind from inside the mirror, that film was directly structured around images. It was intended to be seen as we have it. Watching Page it becomes increasingly obvious that a story deeply pertains to what we see; as was customary in Japan at the time, that story was meant to be narrated to the audience by a benshi, a narrator supplied by each theater. We may cobble together a view of that story from other sources, but the intended effect is lost to us.

-there is still the problem that in the version we have approximately one third of the film is missing. Most of it in the end from what I can tell, where the girl is supposed to marry her fiancé (which echoes and wonderfully annotates the scene where the janitor imagines himself reunited with his wife.

Oh, what we have of the film is more than fine, it's actually one of the most captivating visions of the mind in disarray from the time. But it was just not meant to be seen as merely a tone poem. The dreamy flow is clearly flowing somewhere. What we have instead is only what was salvaged from it but at the same time near complete enough, making barely enough sense to stand on its own, that we may be inclined to accept as the full vision.

We can still accept this itself as a fragment of madness and interpret from where our imagination takes us. That is fine, I encourage this.

Rumors have been circulating about a new restored version, hopefully one that - next to a better print - somehow includes the narration, preferably by a benshi, or intertitles at the very least. Until then, no rating from me.

I was increasingly suspicious of this while watching, that I was basically confronted with an incomplete film and so a film impenetrable not wholly by design but only because the keys have been lost to us, or are not attached to the film we are watching and we have to apprehend elsewhere. Doing a little research afterwards only confirmed my doubts. So a little context:

-the film is not the tip of the iceberg of an advanced cinema whose main body is lamentably lost to us; it was saved exactly because it was an exception, a low-budget oddity the filmmaker himself re-discovered in his garden shed. The majority of silent Japanese cinema - whose final traces were eclipsed in the aftermath of WWII - were generic studio reworkings of popular material.

-it is not the product of an 'isolated cinematic environment free of influence', rather a studied attempt to recreate what the French avant-garde was pioneering at the time; so yes, the superimpositions, the haze of motions and details, the rapid-fire montage, all of them tools in the attempt to offer us a glimpse of the fractured, elusive reality of the mind, available tools at the time that Kinugasa knew from other films.

-so even though the idea of a janitor coming to work in a mental hospital may carry hues of Caligari, the film itself is from the line of what in France was called impressionism; the films of Epstein, L'Herbier, Gance.

-most importantly, even though the closest parable I can think of is Menilmontant, another French film from the same year that in place of story tried to paint with only images a state of mind from inside the mirror, that film was directly structured around images. It was intended to be seen as we have it. Watching Page it becomes increasingly obvious that a story deeply pertains to what we see; as was customary in Japan at the time, that story was meant to be narrated to the audience by a benshi, a narrator supplied by each theater. We may cobble together a view of that story from other sources, but the intended effect is lost to us.

-there is still the problem that in the version we have approximately one third of the film is missing. Most of it in the end from what I can tell, where the girl is supposed to marry her fiancé (which echoes and wonderfully annotates the scene where the janitor imagines himself reunited with his wife.

Oh, what we have of the film is more than fine, it's actually one of the most captivating visions of the mind in disarray from the time. But it was just not meant to be seen as merely a tone poem. The dreamy flow is clearly flowing somewhere. What we have instead is only what was salvaged from it but at the same time near complete enough, making barely enough sense to stand on its own, that we may be inclined to accept as the full vision.

We can still accept this itself as a fragment of madness and interpret from where our imagination takes us. That is fine, I encourage this.

Rumors have been circulating about a new restored version, hopefully one that - next to a better print - somehow includes the narration, preferably by a benshi, or intertitles at the very least. Until then, no rating from me.

10mjneu59

Film history has been negligent in recognizing this landmark silent drama, made in 1926 by pioneering Japanese director Teinosuke Kinugasa, but unknown until 1971, when a surviving print was (literally) unearthed in the director's garden shed. The film was produced in an isolated creative environment far removed from any foreign influence, but is nevertheless a masterpiece of imagery and editing, revealing a stunning visual flair and employing montage techniques as skillfully as anyone since Eisenstein. It tells a powerful, hallucinatory story of a janitor in an insane asylum who wants desperately to help his inmate wife after she attempts suicide, and like Murnau's 'The Last Laugh' unfolds without the crutch of intertitles. The film has aged remarkable little after the better part of a century in limbo, but since its belated rediscovery has yet to earn the acclaim and evaluation it deserves.

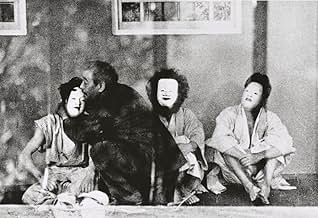

If you do not think you can take graphic scenes of mentally unstable people, this film is not for you.This story is about a man who takes a job at a local mental institution so he can be near his wife, who has gone mad. Throughout this long thought lost film you see clearly harrowing images of people at the institution. The soundtrack only adds to the foreboding. There are people lying catatonic and there is a dancer who doesn't stop dancing until she drops to the floor, exhausted. The film is 59 minutes long, I think it was originally longer but this was all that was found. There are no inter titles, its a silent film. In Japan, I am certain the benshi narrated the story in theaters, but your imagination has to follow this story. So, why a 7? It is daring, unflinching, brave and both ugly and not at the same time. As a point of reference only, Guy Maddin's work approaches this. Just know going in there is no happiness here. You won't soon forget this film. Best idea: Don't watch it before bedtime, it will stay with you.

Very few Japanese films exist from the silent period. In fact, statistics show that only 1% of around 7,000 productions are represented in the a catalogue of the silent cycle. Director Teinosuke Kinugasa's Kurutta Ippeji (also known as A Page of Madness) was thought lost (and perhaps forgotten) until he himself discovered a print in a warehouse in 1971. He diligently produced a new music soundtrack and re-released it. This is the first example of a silent film from Japan, and have to say that the world should be thankful that Kinugasa discovered this avant- garde little master work.

The film was produced with an avant garde group of artists, known as Shinkankak-ha (School of New Perceptions), an experimental art movement that rejected naturalism, or realism, and was highly influenced by European art movements such as Expressionism, Dada, and Cubism, and evidently uses the techniques found in Soviet Montage, particularly Sergei Eisenstein - fundamentally, as this project deals with madness, it would be easy to draw parallels with Robert Weine's seminal horror film Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (1920). What the art trope bring to this extreme nightmare are those exaggerated, pointed and alarmist movements like the expressionist acting styles being used in European film and stage work - but happens to find its own stylistic flourishes, and colloquial "voice" (for want of a better word).

Kurutta ippeji's simplistic story focuses on a man (Masuo Inoue) whom has taken a job as a janitor in an asylum, so that he may be close to his wife (Yoshie Nakagawa), who has been condemned. His aim is to aid in her escape from the dogmatic institution. However, when the break-out is orchestrated, her madness has enveloped her, and she is unwilling to leave with her husband. The couples daughter (Ayako Iijima) visits the asylum to advise her mother of her engagement, which leads to a maelstrom of fantastically abstract flashbacks, giving light to the reasons the mother is condemned.

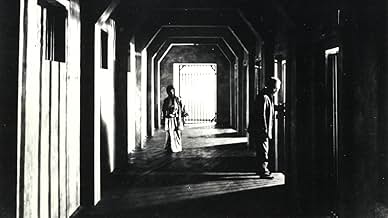

The films style is so incredibly complex and technically brilliant. In the opening sequence, the jarring compositions (both beautiful and haunting), superimposition's, and quick montage editing, creates an assault on the senses that is difficult to break away from - torrential rain falls the scenery in shots of the asylum, expressionist compositions of wind-battered tree branches clashing with windows, and the sight of a woman riddled in madness. The use of superimposition becomes greater as the film moves into crescendo, and these layers portray climatically the merger of madness and modernity. Do we witness the ghosts that haunt the corridors of the asylum? Or are these the devastating spectre's of modernity, and the destruction of tradition? An ironic speculation perhaps, considering the mechanics of cinema production and exhibition.

To a modern audience, silent cinema is often a difficult watch. This film is of particular note for this argument. Kurutta ippeji has no title cards describing dialogue, or internal action, which makes it difficult to follow at times. But as with all 1920's Japanese cinema, the films were always accompanied by narration - a storyteller known colloquially as a benshi. But this small infraction does not hamper an incredibly dazzling piece of early experimental cinema, and one that should be viewed by any film enthusiast, at least for posterity - if not for a formative education on the stylistic diversity of film as art.

www.the-wrath-of-blog.blogspot.com

The film was produced with an avant garde group of artists, known as Shinkankak-ha (School of New Perceptions), an experimental art movement that rejected naturalism, or realism, and was highly influenced by European art movements such as Expressionism, Dada, and Cubism, and evidently uses the techniques found in Soviet Montage, particularly Sergei Eisenstein - fundamentally, as this project deals with madness, it would be easy to draw parallels with Robert Weine's seminal horror film Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (1920). What the art trope bring to this extreme nightmare are those exaggerated, pointed and alarmist movements like the expressionist acting styles being used in European film and stage work - but happens to find its own stylistic flourishes, and colloquial "voice" (for want of a better word).

Kurutta ippeji's simplistic story focuses on a man (Masuo Inoue) whom has taken a job as a janitor in an asylum, so that he may be close to his wife (Yoshie Nakagawa), who has been condemned. His aim is to aid in her escape from the dogmatic institution. However, when the break-out is orchestrated, her madness has enveloped her, and she is unwilling to leave with her husband. The couples daughter (Ayako Iijima) visits the asylum to advise her mother of her engagement, which leads to a maelstrom of fantastically abstract flashbacks, giving light to the reasons the mother is condemned.

The films style is so incredibly complex and technically brilliant. In the opening sequence, the jarring compositions (both beautiful and haunting), superimposition's, and quick montage editing, creates an assault on the senses that is difficult to break away from - torrential rain falls the scenery in shots of the asylum, expressionist compositions of wind-battered tree branches clashing with windows, and the sight of a woman riddled in madness. The use of superimposition becomes greater as the film moves into crescendo, and these layers portray climatically the merger of madness and modernity. Do we witness the ghosts that haunt the corridors of the asylum? Or are these the devastating spectre's of modernity, and the destruction of tradition? An ironic speculation perhaps, considering the mechanics of cinema production and exhibition.

To a modern audience, silent cinema is often a difficult watch. This film is of particular note for this argument. Kurutta ippeji has no title cards describing dialogue, or internal action, which makes it difficult to follow at times. But as with all 1920's Japanese cinema, the films were always accompanied by narration - a storyteller known colloquially as a benshi. But this small infraction does not hamper an incredibly dazzling piece of early experimental cinema, and one that should be viewed by any film enthusiast, at least for posterity - if not for a formative education on the stylistic diversity of film as art.

www.the-wrath-of-blog.blogspot.com

Lo sapevi?

- QuizThis film was deemed lost for more than forty years, but it was rediscovered by its director, Teinosuke Kinugasa, in a rice cans in 1971.

- Versioni alternativeReissued in Japan in 1973 with musical score replacing original benshi.

- ConnessioniFeatured in Storia del cinema: Un'odissea: The Golden Age of World Cinema (2011)

I più visti

Accedi per valutare e creare un elenco di titoli salvati per ottenere consigli personalizzati

- How long is A Page of Madness?Powered by Alexa

Dettagli

- Data di uscita

- Paese di origine

- Lingue

- Celebre anche come

- Una pagina folle

- Luoghi delle riprese

- Kyoto, Giappone(Studio)

- Aziende produttrici

- Vedi altri crediti dell’azienda su IMDbPro

Botteghino

- Budget

- 20.000 JPY (previsto)

- Tempo di esecuzione1 ora 10 minuti

- Colore

- Mix di suoni

- Proporzioni

- 1.33 : 1

Contribuisci a questa pagina

Suggerisci una modifica o aggiungi i contenuti mancanti