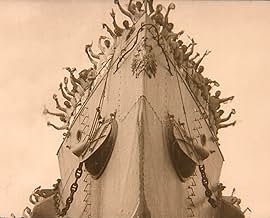

Nel mezzo della Rivoluzione Russa del 1905, l'equipaggio della nave da guerra Potemkin si ammutina contro il regime brutale e tirannico degli ufficiali di servizio sulla nave. Ne consegue un... Leggi tuttoNel mezzo della Rivoluzione Russa del 1905, l'equipaggio della nave da guerra Potemkin si ammutina contro il regime brutale e tirannico degli ufficiali di servizio sulla nave. Ne consegue una manifestazione per le strade di Odessa che sfocia in un massacro da parte della polizia.Nel mezzo della Rivoluzione Russa del 1905, l'equipaggio della nave da guerra Potemkin si ammutina contro il regime brutale e tirannico degli ufficiali di servizio sulla nave. Ne consegue una manifestazione per le strade di Odessa che sfocia in un massacro da parte della polizia.

- Regia

- Sceneggiatura

- Star

- Premi

- 1 vittoria in totale

- Young Sailor Flogged While Sleeping

- (as I. Bobrov)

- Woman With Pince-nez

- (as N. Poltavtseva)

- Student

- (as Brodsky)

- Odessa Citizen

- (as Sergei M. Eisenstein)

- Recruit

- (as A. Fait)

Riepilogo

Recensioni in evidenza

Eisenstein was a revolutionary artist, but at the genius level. Not wanting to make a historical drama, Eisenstein used visual texture to give the film a newsreel-look so that the viewer feels he is eavesdropping on a thrilling and politically revolutionary story. This technique is used by Pontecorvo's The Battle of Algiers.

Unlike Pontecorvo, Eisenstein relied on typage, or the casting of non-professionals who had striking physical appearances. The extraordinary faces of the cast are what one remembers from Potemkin. This technique is later used by Frank Capra in Mr. Deeds Goes to Town and Meet John Doe. But in Potemkin, no one individual is cast as a hero or heroine. The story is told through a series of scenes that are combined in a special effect known as montage--the editing and selection of short segments to produce a desired effect on the viewer. D.W. Griffith also used the montage, but no one mastered it so well as Eisenstein.

The artistic filming of the crew sleeping in their hammocks is complemented by the graceful swinging of tables suspended from chains in the galley. In contrast the confrontation between the crew and their officers is charged with electricity and the clenched fists of the masses demonstrate their rage with injustice.

Eisenstein introduced the technique of showing an action and repeating it again but from a slightly different angle to demonstrate intensity. The breaking of a plate bearing the words "Give Us This Day Our Daily Bread" signifies the beginning of the end. This technique is used in Last Year at Marienbad. Also, when the ship's surgeon is tossed over the side, his pince-nez dangles from the rigging. It was these glasses that the officer used to inspect and pass the maggot-infested meat. This sequence ties the punishment to the corruption of the czarist-era.

The most noted sequence in the film, and perhaps in all of film history, is The Odessa Steps. The broad expanse of the steps are filled with hundreds of extras. Rapid and dramatic violence is always suggested and not explicit yet the visual images of the deaths of a few will last in the minds of the viewer forever.

The angular shots of marching boots and legs descending the steps are cleverly accentuated with long menacing shadows from a sun at the top of the steps. The pace of the sequence is deliberately varied between the marching soldiers and a few civilians who summon up courage to beg them to stop. A close up of a woman's face frozen in horror after being struck by a soldier's sword is the direct antecedent of the bank teller in Bonnie in Clyde and gives a lasting impression of the horror of the czarist regime.

The death of a young mother leads to a baby carriage careening down the steps in a sequence that has been copied by Hitchcock in Foreign Correspondent, by Terry Gilliam in Brazil, and Brian DePalma in The Untouchables. This sequence is shown repeatedly from various angles thus drawing out what probably was only a five second event.

Potemkin is a film that immortalizes the revolutionary spirit, celebrates it for those already committed, and propagandizes it for the unconverted. It seethes of fire and roars with the senseless injustices of the decadent czarist regime. Its greatest impact has been on film students who have borrowed and only slightly improved on techniques invented in Russia several generations ago.

Eisenstein had already made a more successful film before this, more reflexively about the seeing eye. So, even though there is a more rip-roaring story here, you may have to struggle a bit with how faceless appears this world to us, these days so accustomed to the paradigm of the individual hero. But Eisenstein was an architect - literally, as well as in film - and so space matters, our relationship with space through motion matters.

In other words; this may have been preserved to us as a museum piece, which is an indictment of our own understanding of cinema as coming down to us by the books and lists of assorted institutions, but at the time it was part of the most deeply revolutionary film school, one that rigged trains as movie studios and sent them scurrying the countryside to film the people and show them to themselves. I mean, here was a man - Eisenstein - who studied Japanese ideograms to understand synthesized image; who discovered that editing to the beats of the human heart affected more, true or false it shows the desire to both know and reach out.

Our cinematic ideas have mostly regressed into mechanical reproduction since the time when these things were first engineered. Oh, there's plenty of Eisenstein every time you open the TV, but none of it is knowing. It's merely a matter of going-through-the-motions, without the blueprint anymore.

So, look at how crowds are orchestrally conducted through stark geometries, how Eisenstein dissects cinematic space with even a stationary camera. But this type of cinema meant to agitate the people, was never about a thought, it was about an action.

And so with this one. There is the one hero who, although dead, calls out to the people. They rush to him, like ships around their harbor. So on board the ship there is valiant effort for brotherhood and justice, inspired revolution; portside is the motherland, cheering the effort with aplomb. And in the end there is the hero ship, itself filled with heroes, now passing through a sea corridor lined with brother ships, all cheering the one. You can imagine the people cheering at the cinema, who had been there to cheer the real thing years ago.

And when I say 'the real thing' I mean the revolution 8 years before; the Potemkin event depicted here was purely fictional. Yet by the famous steps at Odessa is erected a monument to the fictional sailors, what better example of cinema shaping reality?

So yes, it is a revolutionary film. We may be inclined to make fun of the notions, or worse yet dismiss off-hand because of hindsight knowledge. But this was a film celebrating a time when the world seemed like it could be new again. Then came Stalin and, ironically, vanished all these filmmakers that sung the paeans.

Montage, which was not just Eistenstein's knack but also his life's blood early in his career, is often misused in the present cinema, or if not misused then in an improper context for the story. Sometimes montage is used now as just another device to get from point A to point B. Montage was something else for Eisenstein; he was trying to communicate in the most direct way that he could the urgency, the passion(s), and the ultimate tragedies that were in the Russian people at the time and place. Even if one doesn't see all of Eisenstein's narrative or traditional 'story' ideas to have much grounding (Kubrick has said this), one can't deny the power of seeing the ships arriving at the harbor, the people on the stairs, and the soldiers coming at them every which way with guns. Some may find it hard to believe this was done in the 20's; it has that power like the Passion of Joan of Arc to over-pass its time and remain in importance if only in terms of technique and emotion.

Of course, one could go on for books (which have been written hundreds of times over, not the least of which by Eisenstein himself). On the film in and of itself, Battleship Potemkin is really more like a dramatized newsreel than a specific story in a movie. The first segment is also one of the great sequences in film, as a mutiny is plotted against the Captain and other head-ups of a certain Ship. This is detailed almost in a manipulative way, but somehow extremely effective; montage is used here as well, but in spurts of energy that capture the eye. Other times Eisenstein is more content to just let the images speak for themselves, as the soldiers grow weary without food and water. He isn't one of those directors who will try to get all sides to the story; he is, of course, very much early 20th century Russian, but he is nothing else but honest with how he sees his themes and style, and that is what wins over in the end.

Some may want to check it outside of film-school, as the 'Stairs' sequence is like one of those landmarks of severe tragedy on film, displaying the ugly side of revolution. Eisenstein may not be one of the more 'accessible' silent-film directors, but if montage, detail in the frame, non-actors, and Bolshevik themes are your cup of tea, it's truly one of the must sees of a lifetime.

The movie certainly deserves the praise that it gets both for the influence that it has had, and for some ideas that for the time were most creative. The famed 'Odessa Steps' sequence alone demonstrates both fine technical skill and a keen awareness of how to drive home an image to an audience. It deserves to be one of cinema's best remembered sequences. Some of the other scenes also demonstrate, to a lesser degree, the same kind of skill.

It says a lot for how effective all of the visuals are that so many viewers think so highly of "Battleship Potemkin" despite a story that is sometimes heavy-handed, and despite characters and acting that are both rather thin. These features might simply stem from the collectivist philosophy that lies behind the story, and they are obscured most of the time by Eisenstein's unsurpassed ability to present pictures that viewers will not forget.

Despite the flaws, this is a movie that most fans of silent films, and anyone interested in the history of movies, will want to see. There's nothing else in its era that's quite like it.

'Potyomkin' is a film that NEEDS to be seen as one entity, not to be picked at. Don't just watch those clip shows where they only present the 'Odessa steps' sequence and then move on to 'Citizen Kane' or 'The Godfather', see it all in it's glorious 75-minute running time to really understand and enjoy it. Don't expect every infinitesimal detail to be perfect though, I mean the acting of the '20s silent era makes 'Scooby Doo' look like a master of understated realism, certain plot points may seem illogical and some of the battle sequences look dated, but it is still an immensely enjoyable movie.

The most memorable moments in the film are the mutiny on the battleship, Vakulinchuk's body falling off the ship, the sailor under the tent at the end of the pier, the mother holding her dead child, the baby carriage on the Odessa steps and the lion rising up to roar as further carnage ensues. For each new pair of eyes that look upon it, 'The Battleship Potemkin' comes alive once again.

Lo sapevi?

- QuizThe film censorship boards of several countries felt this movie would spread communism. France imposed a ban after a brief run in 1925; it lifted it in 1953 after the death of Russian leader Joseph Stalin. The UK banned it until 1954.

- BlooperIn the Imperial squadron near the end of the film, there are close-ups of triple gun turrets of Gangut-class dreadnought. It possibly was made this way to show the power of Imperial fleet, but battleships of 1905 were much smaller pre-dreadnoughts, with twin turrets only, just like "Potemkin". "Ganguts" entered service in 1914.

- Versioni alternativeSergei Eisenstein's premiere version opened with an unattributed quote from Leon Trotsky's "1905": The spirit of mutiny swept the land. A tremendous, mysterious process was taking place in countless hearts: the individual personality became dissolved in the mass, and the mass itself became dissolved in the revolutionary impetus. This quote was removed by Soviet censors in 1934, and replaced by a quotation from V.I. Lenin's "Revolutionary Days": Revolution is war. Of all the wars known in history, it is the only lawful, rightful, just and truly great war...In Russia this war has been declared and won. The original text was restored in 2004.

- ConnessioniEdited into Seeds of Freedom (1943)

I più visti

- How long is Battleship Potemkin?Powered by Alexa

Dettagli

- Data di uscita

- Paese di origine

- Lingue

- Celebre anche come

- Battleship Potemkin

- Luoghi delle riprese

- Sevastopol, Crimea, Ucraina(battleship scenes)

- Azienda produttrice

- Vedi altri crediti dell’azienda su IMDbPro

Botteghino

- Lordo Stati Uniti e Canada

- 51.198 USD

- Fine settimana di apertura Stati Uniti e Canada

- 5641 USD

- 16 gen 2011

- Lordo in tutto il mondo

- 62.723 USD

- Tempo di esecuzione

- 1h 15min(75 min)

- Colore

- Mix di suoni

- Proporzioni

- 1.33 : 1