VALUTAZIONE IMDb

7,6/10

9108

LA TUA VALUTAZIONE

Un gruppo di operai di fabbrica oppressi sciopera nella Russia prima della rivoluzione.Un gruppo di operai di fabbrica oppressi sciopera nella Russia prima della rivoluzione.Un gruppo di operai di fabbrica oppressi sciopera nella Russia prima della rivoluzione.

- Regia

- Sceneggiatura

- Star

Leonid Alekseev

- Factory Sleuth

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

Daniil Antonovich

- Worker

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

Pyotr Malek

- Police Spy

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

Misha Mamin

- Baby Boy

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

Pavel Poltoratskiy

- Stockholder

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

Recensioni in evidenza

More so with the Soviets than with any other film school, we need to resupply the context. The image reigns supreme but not in ways we may understand today, as aesthetic accomplishment or space for contemplation. It is about immediate understanding as formed in the eye so that narrative - the tool by which the Czarist or the bourgeois wrote history, thus a suspicious element - is bypassed, the eye and not the mind is thus tasked to construct. Meant to instruct ideological fervor in a generally unsophisticated audience, these films, propaganda we call them now, stirred into action, not thought. This was in tacit understanding with Marxist principles, that demanded history be foremostly changed than understood.

Change; action; seeing. This is the causal chain the Soviets immersed themselves in, looking for the keys that guide vision.

So, these people eventually grew to know more about the mechanisms that control the image than any other group of people anywhere else in history. They were theoreticians, scientists of film, as well as the actual makers; a now extinct combination, much to our dismay. Eisenstein - and Vertov - were key figures; I mean, here was a man who studied Japanese ideograms to understand synthesized image; who discovered that editing to the beats of the human heart affected more.

So, we are talking about a reflexive cinema, about rhythm as opposed to melody. It's just as well with these films that the narrative content is pretty much discarded by now, even though the agitprop often agitated in the right direction; or have we forgotten that workers, at some point, were truly horribly exploited and that the 8-hour workshift was a bloody struggle? But, being able to quickly sift through caricatures - the fat, capitalist factory owner, the well-groomed, pigheaded stockholders slobbering on their fat cigars - and process the easy distinctions between collective good and the individual selfishness, means we can concentrate on rhythm. On how these thin caricatures that should have been harmless, yet are charged with a power that moves and affects.

It's about the mechanisms that control the image; it is a unique opportunity to have this film, it shows the very image being controlled. The end of the first part, with the shot of huge factory machinery whirring into motion as already the uprising is being set into motion; and later, the hand of the cruel stockholder superimposed over the crowd of strikers, clutching, controlling.

Eisenstein is so adept in his touch that the film is, at times, action, comedy, chamber drama, detective film, policier, paean, sobering catastrophe.

The most amazing sequence; we are with the strikers in an outdoors gathering, as the leader is laying down their demands, yet immediately transported to the lavish mansion of the stockholders as they read them with anger; there is some talk and eventually, satisfied, gleeful, they break out the drinks, an intertitle informs us of their answer to the demands, a polite, civilized refusal 'after careful consideration', while immediately the mounted police is storming the outdoors camp.

It is a stunning display of cinema, how time and space are contorted to accommodate for our passage through and yet the result is a dialectic between images as eminently designed for the eye - not the mind. We see, ergo we know - and are.

Change; action; seeing. This is the causal chain the Soviets immersed themselves in, looking for the keys that guide vision.

So, these people eventually grew to know more about the mechanisms that control the image than any other group of people anywhere else in history. They were theoreticians, scientists of film, as well as the actual makers; a now extinct combination, much to our dismay. Eisenstein - and Vertov - were key figures; I mean, here was a man who studied Japanese ideograms to understand synthesized image; who discovered that editing to the beats of the human heart affected more.

So, we are talking about a reflexive cinema, about rhythm as opposed to melody. It's just as well with these films that the narrative content is pretty much discarded by now, even though the agitprop often agitated in the right direction; or have we forgotten that workers, at some point, were truly horribly exploited and that the 8-hour workshift was a bloody struggle? But, being able to quickly sift through caricatures - the fat, capitalist factory owner, the well-groomed, pigheaded stockholders slobbering on their fat cigars - and process the easy distinctions between collective good and the individual selfishness, means we can concentrate on rhythm. On how these thin caricatures that should have been harmless, yet are charged with a power that moves and affects.

It's about the mechanisms that control the image; it is a unique opportunity to have this film, it shows the very image being controlled. The end of the first part, with the shot of huge factory machinery whirring into motion as already the uprising is being set into motion; and later, the hand of the cruel stockholder superimposed over the crowd of strikers, clutching, controlling.

Eisenstein is so adept in his touch that the film is, at times, action, comedy, chamber drama, detective film, policier, paean, sobering catastrophe.

The most amazing sequence; we are with the strikers in an outdoors gathering, as the leader is laying down their demands, yet immediately transported to the lavish mansion of the stockholders as they read them with anger; there is some talk and eventually, satisfied, gleeful, they break out the drinks, an intertitle informs us of their answer to the demands, a polite, civilized refusal 'after careful consideration', while immediately the mounted police is storming the outdoors camp.

It is a stunning display of cinema, how time and space are contorted to accommodate for our passage through and yet the result is a dialectic between images as eminently designed for the eye - not the mind. We see, ergo we know - and are.

Sergei Eisenstein's "Strike", like his more well-known films, is interesting and contains some memorable imagery. The story is worthwhile in itself, and it repays careful attention because of the considerable detail that is shown using Eisenstein's distinctive approach. It lacks any particularly interesting characters, but then, so did "Battleship Potemkin". Only an occasional lack of polish sets this apart from Eisenstein's later films.

The story starts with the situations that provoke the strike, and then follows developments on both sides of the dispute. It becomes surprisingly involved for what seems at first to be a simple confrontation. There is quite an assortment of situations, settings, and characters. On occasion, the images are overdone, occasionally even off-putting, but you can already see the creative use of imagery that Eisenstein would later use so effectively.

"Strike" will probably be of interest mainly to those who already appreciate Eisenstein's films, but it is worth seeing. It is really only a cut below "Potemkin", which itself, though generally the most-praised of his films, might actually be surpassed by some of his later works. In any case, "Strike" displays the same kind of style, and has several of the characteristics of the fine classics that were to come.

The story starts with the situations that provoke the strike, and then follows developments on both sides of the dispute. It becomes surprisingly involved for what seems at first to be a simple confrontation. There is quite an assortment of situations, settings, and characters. On occasion, the images are overdone, occasionally even off-putting, but you can already see the creative use of imagery that Eisenstein would later use so effectively.

"Strike" will probably be of interest mainly to those who already appreciate Eisenstein's films, but it is worth seeing. It is really only a cut below "Potemkin", which itself, though generally the most-praised of his films, might actually be surpassed by some of his later works. In any case, "Strike" displays the same kind of style, and has several of the characteristics of the fine classics that were to come.

This is an impressive looking piece of Communists propaganda, that glorify the common worker, from Russian movie-making pioneer Sergei M. Eisenstein.

It's one of Eisenstein's first movies, which also means that he was experimenting a lot in the movie, with many different compositions and with fantastic fast editing that give the movie pace and make the sequences more exciting. Some of the sequences are highly creative and artistic looking, with great cinematography and camera-angels. It makes "Stachka" real eye-candy to watch. It's a real innovative movie and by watching it you realize that there was a real craftsman at work. It's an absolutely brilliantly directed movie!

Of course if you're looking for a movie with a good story and compelling characters, look further. The movie itself is pretty simple with its story and uses deliciously stereotypical characters, such as the capitalistic, fat, cigar smoking and drinking factory owners. The movie uses so many stereotypes that the movie intentionally also works out as an humorous movie. It's very welcome, since the movie in general in its story is very serious and tries to send out a message.

The story is perhaps easier to follow than in most other Eisenstein movies. It's a very simple story that on paper sounds to weak and uninteresting to fill a 90+ movie with. Yet the movie never bores and always remains interesting and 'enjoyable' to follow, also not in the least thanks to the rapid editing that makes sure none of the sequences go on for too long and allow the sequences to speak for itself, rather then relying on the actors their performances or title-cards.

An essential viewing for movie-lovers!

9/10

http://bobafett1138.blogspot.com/

It's one of Eisenstein's first movies, which also means that he was experimenting a lot in the movie, with many different compositions and with fantastic fast editing that give the movie pace and make the sequences more exciting. Some of the sequences are highly creative and artistic looking, with great cinematography and camera-angels. It makes "Stachka" real eye-candy to watch. It's a real innovative movie and by watching it you realize that there was a real craftsman at work. It's an absolutely brilliantly directed movie!

Of course if you're looking for a movie with a good story and compelling characters, look further. The movie itself is pretty simple with its story and uses deliciously stereotypical characters, such as the capitalistic, fat, cigar smoking and drinking factory owners. The movie uses so many stereotypes that the movie intentionally also works out as an humorous movie. It's very welcome, since the movie in general in its story is very serious and tries to send out a message.

The story is perhaps easier to follow than in most other Eisenstein movies. It's a very simple story that on paper sounds to weak and uninteresting to fill a 90+ movie with. Yet the movie never bores and always remains interesting and 'enjoyable' to follow, also not in the least thanks to the rapid editing that makes sure none of the sequences go on for too long and allow the sequences to speak for itself, rather then relying on the actors their performances or title-cards.

An essential viewing for movie-lovers!

9/10

http://bobafett1138.blogspot.com/

Eisenstein's most purely enjoyable film, possibly because the theorems are more lifelike. In many ways a comedy, as the villains (military, police, factory owners, underworld scabs) are caricatured and dehumanised, which makes the eventual horrors all the more shocking. The workers are, of course, idealised, but their paradise of laziness seems odd for a Communist work.

Montage is the thing, as ever with Eisenstein, both in terms of connecting images to create startling insights, and in making tense, exciting and inevitable the action; but there is an astonishing attention to compositional detail too, most haunting perhaps being the empty, abandoned, impotent, machine-heavy factories, or the vast-stepped drawing rooms of the bloated capitalists.

Montage is the thing, as ever with Eisenstein, both in terms of connecting images to create startling insights, and in making tense, exciting and inevitable the action; but there is an astonishing attention to compositional detail too, most haunting perhaps being the empty, abandoned, impotent, machine-heavy factories, or the vast-stepped drawing rooms of the bloated capitalists.

This is Eisenstein's directorial debut and alongside Citizen Kane it may be one of the most important debuts in the history of film showcasing a fully-fledged artistic maturity. This is a fictitious narrative-driven movie though it is very consonant with reality. As a Communist Eisenstein's aesthetics was opposed to the "bourgeois" art style that considered the artistic object as a subject of contemplation. Eisenstein advocated in theoretical terms in his books and practically with movies such as this a pragmatic vision of art. Movies should have a purpose; they should mobilize the viewer into action by filing him with emotion.

This strategy is obvious early on with the use of the motto from Lenin that links the idea of organized workers and that of social action in an equation of efficiency. The movie tries to prove that the workers are entitled to organization and that only in such a manner they could achieve their full potential. The movie focuses on the workers as a group; there are no "characters" as we have grown accustomed to seeing on screen. The collective character of the workers, though, has a very powerful emotional impact on the viewer because Eisenstein knows how to present it:

1) The workers are presented in the factory, in what would appear to Chaplin, for instance as a medium of alienation. Here, the workers seem "at home" because they are so many they balance the non-human elements expressed by the machines. More than this the brilliant montage sequences emphasize that the workers are in peace in their environment, the visual patters give a clear feeling of the strength of the united workers. Later on with the advent of sound the beauty of an industrial landscape will be extraordinarily depicted by Vertov in Enthusiasm;

2) The workers are contrasted with the fat and greedy capitalists. Their environment is luxurious and far more "human" than a factory. However, Eisenstein makes it appear as a place of sin and debauchery. The cigar smoke emphasizes the strength of the exploiter much like the smoke from the furnace shows the force of the factory. There are many correspondences between the two environments which Eisenstein later uses to achieve some of the greatest and most emotionally engaging associative montages ever displayed. One of the most impressive shows a boss squeezing a lemon to fix himself a drink while the workers are squished by the police forces trying to repress the strike;

3) Individuals predominantly appear only when they are associated with heavy dramatic scenes, the innocent worker who commits suicide ( who only functions as the dramatic instigator of the plot without any real emotion displayed for the actual character who dies even if we know his actual name; it is insinuated that a human life has a meaning only as part of larger community), the child who is killed by the police, the spies who serve as much needed humorous debouches that relieve the tension associated with the workers exploitation but that also build up tension in the sense that they show the stupidity of the bosses and of their methods;

4) The key to the movie is its pragmatics. It is after all a propaganda piece and the ending clearly shows it. The advice addressed to the proletarians not to forget is charged with emotion because it discharges a tension that has been carefully build frame by frame at a rampant pace. Even if we disengage with his doctrine we should keep in mind that Eisenstein's genius can only be acknowledged in its cultural context and related to his conception of art's function in a society. We can screen out the propaganda but we must keep the emotion in order to understand this movie today at its full power.

This strategy is obvious early on with the use of the motto from Lenin that links the idea of organized workers and that of social action in an equation of efficiency. The movie tries to prove that the workers are entitled to organization and that only in such a manner they could achieve their full potential. The movie focuses on the workers as a group; there are no "characters" as we have grown accustomed to seeing on screen. The collective character of the workers, though, has a very powerful emotional impact on the viewer because Eisenstein knows how to present it:

1) The workers are presented in the factory, in what would appear to Chaplin, for instance as a medium of alienation. Here, the workers seem "at home" because they are so many they balance the non-human elements expressed by the machines. More than this the brilliant montage sequences emphasize that the workers are in peace in their environment, the visual patters give a clear feeling of the strength of the united workers. Later on with the advent of sound the beauty of an industrial landscape will be extraordinarily depicted by Vertov in Enthusiasm;

2) The workers are contrasted with the fat and greedy capitalists. Their environment is luxurious and far more "human" than a factory. However, Eisenstein makes it appear as a place of sin and debauchery. The cigar smoke emphasizes the strength of the exploiter much like the smoke from the furnace shows the force of the factory. There are many correspondences between the two environments which Eisenstein later uses to achieve some of the greatest and most emotionally engaging associative montages ever displayed. One of the most impressive shows a boss squeezing a lemon to fix himself a drink while the workers are squished by the police forces trying to repress the strike;

3) Individuals predominantly appear only when they are associated with heavy dramatic scenes, the innocent worker who commits suicide ( who only functions as the dramatic instigator of the plot without any real emotion displayed for the actual character who dies even if we know his actual name; it is insinuated that a human life has a meaning only as part of larger community), the child who is killed by the police, the spies who serve as much needed humorous debouches that relieve the tension associated with the workers exploitation but that also build up tension in the sense that they show the stupidity of the bosses and of their methods;

4) The key to the movie is its pragmatics. It is after all a propaganda piece and the ending clearly shows it. The advice addressed to the proletarians not to forget is charged with emotion because it discharges a tension that has been carefully build frame by frame at a rampant pace. Even if we disengage with his doctrine we should keep in mind that Eisenstein's genius can only be acknowledged in its cultural context and related to his conception of art's function in a society. We can screen out the propaganda but we must keep the emotion in order to understand this movie today at its full power.

Lo sapevi?

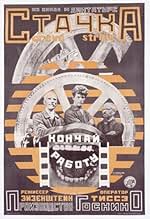

- QuizStrike (Russian: Sciopero (1925)) is a Soviet silent propaganda film edited and directed by Sergei Eisenstein. Originating as one entry out of a proposed seven-part series titled "Towards Dictatorship of the Proletariat," Strike was a joint collaboration between the Proletcult Theatre and the film studio Goskino. As Eisenstein's first full-length feature film, it marked his transition from theatre to cinema, and his next film La corazzata Potemkin (1925) (Russian: Bronenosets Potyomkin) emerged from the same film cycle.

- BlooperThe story is set in 1903. Throughout the film, automobiles from the 1920s appear on streets. One is the 1920s auto that the worker (who stole the administrators' posted reply to workers' demands) tried to use to escape police goons during a nighttime rainstorm. When upper-class women appear, they are wearing contemporary 1920s fashions, and the popular music that's on the sound track is also from the 1920s.

- Citazioni

Title Card: At the factory, all is calm. BUT. The boys are restless.

- Versioni alternativeThe film was restored at Gorky Film Studio in 1969.

- ConnessioniEdited into Ten Days That Shook the World (1967)

I più visti

Accedi per valutare e creare un elenco di titoli salvati per ottenere consigli personalizzati

- How long is Strike?Powered by Alexa

Dettagli

- Tempo di esecuzione1 ora 22 minuti

- Colore

- Mix di suoni

- Proporzioni

- 1.33 : 1

Contribuisci a questa pagina

Suggerisci una modifica o aggiungi i contenuti mancanti