VALUTAZIONE IMDb

8,0/10

16.015

LA TUA VALUTAZIONE

Aggiungi una trama nella tua linguaAn aging doorman is forced to face the scorn of his friends, neighbors and society after being fired from his prestigious job at a luxurious hotel.An aging doorman is forced to face the scorn of his friends, neighbors and society after being fired from his prestigious job at a luxurious hotel.An aging doorman is forced to face the scorn of his friends, neighbors and society after being fired from his prestigious job at a luxurious hotel.

- Regia

- Sceneggiatura

- Star

- Premi

- 2 vittorie totali

O.E. Hasse

- Small Role

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

Harald Madsen

- Wedding Musician

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

Neumann-Schüler

- Small Role

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

Carl Schenstrøm

- Wedding Musician

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

Erich Schönfelder

- Small role

- (non citato nei titoli originali)

Recensioni in evidenza

F. W Murnau works are rare things - he made very few compared to other directors of his day, and many of those he did make have been lost. The reason he made so few can perhaps be understood by watching The Last Laugh. Like Chaplin, Kubrick and Leone, the effort that went into a single picture was the same effort another director might spread across ten. Nosferatu, his famous Dracula story, is great, and i hear his Faust and Sunrise are also things to behold - but many regard "The Last Laugh" as his masterwork, and also one of the greatest movies of all time. Lillian Gish once said that she never approved of the talkies - she felt that silents were starting to create a whole new art form. She was right, but the proof of this can not be seen in the work of Griffith, who was her frequent collaborator, and who she probably was thinking about when she made this statement - but in the work of German director F. W Murnau.

D. W Griffith is usually shunned for his stance on racial issues and praised for his abilities as an influential film artist. I believe he doesn't deserve this praise - and this movie is why. Not only was Griffith about as subtle as a migraine, but watching a Griffith silent, you get more words than images. There's a title card telling you what is about to happen in every image before it does. The images themselves are almost unnecessary - his style is more literary than cinematic. The difference between watching Griffith's Intolerance and watching F. W Murnau's The Last Laugh is like the difference between watching a silent comedy by Hal Roach and one by Charlie Chaplin. The latter of each pair (Murnau and Chaplin) were visualists and artists, using few words, constructing beauty and high emotion through seemingly simple situations (a tramp who discovers a lost child, or a hotel doorman who loses his job, which is the basis of The Last Laugh).

Silent directors strove to and were praised for their ability to tell stories through images alone, as much as possible, and this is one of the reasons silent cinema reached its pinnacle in F. W Murnau's The Last Laugh - which tells the story of a proud hotel doorman (Emil Jennings), who, after many years of service, is demoted from his position to a mens' bathroom attendant. Murnau tells an incredibly sensitive and human tale, showing how much the job meant to him by having him go to work instead of going to his daughter's wedding. He shows how the position made him respected in his neighbourhood, and how he could not face the neighbourhood without his doorman's uniform. And he tells the story almost entirely through images.

There are no title cards telling us what the images are - they are allowed to speak for themselves. The few words used are worked in through letters and signs. Many silent directors cheated and used title cards to explain the images, but only in this movie did the art form of silent movies, which Lillian Gish refers to, take shape.

I was amazed at the level of depth and emotional complexity that Murnau was capable of conveying without resorting to title cards (or their equivalent in talkies, the voice-over). This movie is also notable for its brilliant use of expressionism, and the first brilliant use of a tracking shot. In Murnau's The Last Laugh, silent movies metaphorically were given movement, and learned to run.

D. W Griffith is usually shunned for his stance on racial issues and praised for his abilities as an influential film artist. I believe he doesn't deserve this praise - and this movie is why. Not only was Griffith about as subtle as a migraine, but watching a Griffith silent, you get more words than images. There's a title card telling you what is about to happen in every image before it does. The images themselves are almost unnecessary - his style is more literary than cinematic. The difference between watching Griffith's Intolerance and watching F. W Murnau's The Last Laugh is like the difference between watching a silent comedy by Hal Roach and one by Charlie Chaplin. The latter of each pair (Murnau and Chaplin) were visualists and artists, using few words, constructing beauty and high emotion through seemingly simple situations (a tramp who discovers a lost child, or a hotel doorman who loses his job, which is the basis of The Last Laugh).

Silent directors strove to and were praised for their ability to tell stories through images alone, as much as possible, and this is one of the reasons silent cinema reached its pinnacle in F. W Murnau's The Last Laugh - which tells the story of a proud hotel doorman (Emil Jennings), who, after many years of service, is demoted from his position to a mens' bathroom attendant. Murnau tells an incredibly sensitive and human tale, showing how much the job meant to him by having him go to work instead of going to his daughter's wedding. He shows how the position made him respected in his neighbourhood, and how he could not face the neighbourhood without his doorman's uniform. And he tells the story almost entirely through images.

There are no title cards telling us what the images are - they are allowed to speak for themselves. The few words used are worked in through letters and signs. Many silent directors cheated and used title cards to explain the images, but only in this movie did the art form of silent movies, which Lillian Gish refers to, take shape.

I was amazed at the level of depth and emotional complexity that Murnau was capable of conveying without resorting to title cards (or their equivalent in talkies, the voice-over). This movie is also notable for its brilliant use of expressionism, and the first brilliant use of a tracking shot. In Murnau's The Last Laugh, silent movies metaphorically were given movement, and learned to run.

10thao

The camera work and the sets in this film where so breathtaking and powerful that they changed the film language forever. It is in many ways the Citizen Kane of its time.

It was so revolutionary that Hollywood (Fox) tried desperately to get Murnau to work for them and teach them how to do all these things (which he did some years later). The main revolutionary thing was the fluidity of the camera (or the unchanged camera, as it was called). There was no steady cam at this time, but still they managed to strap the camera to the body of the cameraman without getting a shaky pictures.

The set is just amazing. It is difficult to believe that this is not a real city. All the special effects help also to make this believable (special effects that are still today astonishing and believable).

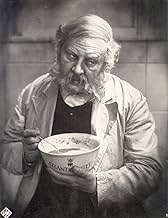

The makeup is also great. Emil Jannings was only 40 years old when he made this film but he really looks like an old man (and acts like one too).

But the greatest thing about this film is how much Murnau manages to say with out the help of inter titles. This is visual storytelling at it's best.

Murnau had come a long way from Nosferatu but he still had a long way to go and a lot to teach us before his untimely death. The Last Laugh is not only one of his best films, it is also most likely his most important one, and one of the most important films in film history.

It was so revolutionary that Hollywood (Fox) tried desperately to get Murnau to work for them and teach them how to do all these things (which he did some years later). The main revolutionary thing was the fluidity of the camera (or the unchanged camera, as it was called). There was no steady cam at this time, but still they managed to strap the camera to the body of the cameraman without getting a shaky pictures.

The set is just amazing. It is difficult to believe that this is not a real city. All the special effects help also to make this believable (special effects that are still today astonishing and believable).

The makeup is also great. Emil Jannings was only 40 years old when he made this film but he really looks like an old man (and acts like one too).

But the greatest thing about this film is how much Murnau manages to say with out the help of inter titles. This is visual storytelling at it's best.

Murnau had come a long way from Nosferatu but he still had a long way to go and a lot to teach us before his untimely death. The Last Laugh is not only one of his best films, it is also most likely his most important one, and one of the most important films in film history.

In 1920s Germany, a hotel doorman takes great pride in both his job and the grand uniform that denotes his position. The uniform earns him the unquestioning respect of his neighbours, so when he is demoted through no fault of his own to the lowly position of lavatory attendant, the doorman is devastated. Stealing the uniform that once was his, he makes a sad attempt to fool his neighbours into thinking he still manages the door of the prestigious Atlantic Hotel but, before long, the truth is uncovered, and the respect they once paid him quickly dissolves.

The Last Laugh stands as one of the finest creations of a remarkable director, F.W. Murnau, whose credits include Nosferatu, Faust and Sunrise. Filmed without use of subtitles – and to appreciate what an astounding achievement this is, try imagining a dramatic film made without any form of dialogue today – Murnau crafts a beautiful, compelling and tragic tale that stands as both testimony to his undoubted skills and to the artistic heights to which silent cinema often aspired.

The venerated German actor Emil Jannings was only 40 when he took on the role of the unnamed porter, and yet a combination of Waldemar Jabs painstaking make-up and Jannings' own ability to convey his character's heartache in simple ways, such as the stoop of his shoulders or a bent leg, means he gives a towering performance that never threatens, however, to overshadow the story being told.

The story revolves as much around the grandiose uniform Jannings wears as it does the man. A symbol of the contemporary German importance attached to uniforms and their unavoidably militaristic connotations, the uniform is portrayed as making the man – and it is only the contentious ending that spins the message that it is not uniforms but compassion and kindness that make men great – not only through the respect he receives from all around him, but in the transformation the porter undergoes whenever he is parted from it. From a ramrod-backed creature of magnificence, with elaborately arranged hair and whiskers, he turns into a fumbling old man with bowed back and shaking hands. In the hands of a lesser actor, the demands of this transformation may have descended into cheap caricature, but Jannings never lets us lose sight of the proud man lurking within the bowed and beaten body.

Karl Freund's camera-work is a revelation in this film, right from the opening shot as we descend with the lift into the foyer of the opulent Atlantic hotel. Numerous tricks are used without drawing attention to their use and thus distracting the viewer from the tragedy that is taking place: the drunken POV shot (achieved by strapping the camera to Freund's chest) in Jannings' flat after his niece's wedding reception; the blurred fantasy sequences (themselves a breakthrough in film narrative) achieved by smearing Vaseline onto the camera lens, and the use of dialectic montage and dolly shots, were all groundbreaking techniques never before used, but copied forevermore.

Murnau directs the film with the assurance of a man at the top of his form – where he would arguably remain until his tragically early death – and the care taken with this film is evident throughout every shot. This is why Murnau made relatively few films in an era when many directors churned them out at a rate of a dozen or more per year. The degree of a director's conscientiousness is always evident on the screen, and it is always a pleasure to view a Murnau film, because it is clear that his commitment to his work was always second to none.

The Last Laugh stands as one of the finest creations of a remarkable director, F.W. Murnau, whose credits include Nosferatu, Faust and Sunrise. Filmed without use of subtitles – and to appreciate what an astounding achievement this is, try imagining a dramatic film made without any form of dialogue today – Murnau crafts a beautiful, compelling and tragic tale that stands as both testimony to his undoubted skills and to the artistic heights to which silent cinema often aspired.

The venerated German actor Emil Jannings was only 40 when he took on the role of the unnamed porter, and yet a combination of Waldemar Jabs painstaking make-up and Jannings' own ability to convey his character's heartache in simple ways, such as the stoop of his shoulders or a bent leg, means he gives a towering performance that never threatens, however, to overshadow the story being told.

The story revolves as much around the grandiose uniform Jannings wears as it does the man. A symbol of the contemporary German importance attached to uniforms and their unavoidably militaristic connotations, the uniform is portrayed as making the man – and it is only the contentious ending that spins the message that it is not uniforms but compassion and kindness that make men great – not only through the respect he receives from all around him, but in the transformation the porter undergoes whenever he is parted from it. From a ramrod-backed creature of magnificence, with elaborately arranged hair and whiskers, he turns into a fumbling old man with bowed back and shaking hands. In the hands of a lesser actor, the demands of this transformation may have descended into cheap caricature, but Jannings never lets us lose sight of the proud man lurking within the bowed and beaten body.

Karl Freund's camera-work is a revelation in this film, right from the opening shot as we descend with the lift into the foyer of the opulent Atlantic hotel. Numerous tricks are used without drawing attention to their use and thus distracting the viewer from the tragedy that is taking place: the drunken POV shot (achieved by strapping the camera to Freund's chest) in Jannings' flat after his niece's wedding reception; the blurred fantasy sequences (themselves a breakthrough in film narrative) achieved by smearing Vaseline onto the camera lens, and the use of dialectic montage and dolly shots, were all groundbreaking techniques never before used, but copied forevermore.

Murnau directs the film with the assurance of a man at the top of his form – where he would arguably remain until his tragically early death – and the care taken with this film is evident throughout every shot. This is why Murnau made relatively few films in an era when many directors churned them out at a rate of a dozen or more per year. The degree of a director's conscientiousness is always evident on the screen, and it is always a pleasure to view a Murnau film, because it is clear that his commitment to his work was always second to none.

I just viewed this film on the pristine Kino video release, having seen a poorish print years ago.

One of the great classics of the German silent cinema, hugely influential, this true work of art not only displays the seemingly limitless resources of the UFA studios, but dares to break constantly with convention, particularly by being a "pure" film and dispensing with intertitles, but most spectacularly in its use of the "subjective" camera--creating as far as I know, the first sustained use of "point of view" in the history of movies, which had hitherto shown us action objectively, as it were: the spectator had always merely "observed," as in a third person narrative. Even Griffith and Bitzer's trucking shots, while including "us" in the action, did not represent another character's point of view. Well, after "the Last Laugh," P.O.V. turns up again and again. (See Abel Gance's "Napoleon.") Today the technique is common (necessary!). The most famous shots in "Der Letzte Mann" include the drunken swaying of the room seen through the Doorman's bleary eyes (cinematographer Karl Freund seated in a large swing and pushed back and forth); the opening shot coming down into the lobby by elevator and exiting the gate; and the astonishing vision of the hotel toppling in slow motion over on the poor doorman after his demotion. And can you believe that first night cityscape with the driving rain was all constructed and shot INDOORS?

However, I must say there is an unfortunate message in this drama, that of the merciless German stereotype: fawning before authority and deriding weakness--humiliating the powerless, admiring, almost worshiping the powerful. This is shown by the doorman's vanity and puffed-up self-image, which hinges, it seems, on a splendid uniform and the deference it alone inspires. Position is everything to him, his family, employers, hotel guests and neighbors. This is a shallow world, indeed, a social mentality that I can imagine, without straining too much, easily leading in a few brief years straight to the all-too-successful Gestapo! (I would add that the ending seems to contradict this, but the ending must be discounted; it is a sheer fantasy, "tacked on," really unrelated to the rest of the film and completely out of character.)

One of the great classics of the German silent cinema, hugely influential, this true work of art not only displays the seemingly limitless resources of the UFA studios, but dares to break constantly with convention, particularly by being a "pure" film and dispensing with intertitles, but most spectacularly in its use of the "subjective" camera--creating as far as I know, the first sustained use of "point of view" in the history of movies, which had hitherto shown us action objectively, as it were: the spectator had always merely "observed," as in a third person narrative. Even Griffith and Bitzer's trucking shots, while including "us" in the action, did not represent another character's point of view. Well, after "the Last Laugh," P.O.V. turns up again and again. (See Abel Gance's "Napoleon.") Today the technique is common (necessary!). The most famous shots in "Der Letzte Mann" include the drunken swaying of the room seen through the Doorman's bleary eyes (cinematographer Karl Freund seated in a large swing and pushed back and forth); the opening shot coming down into the lobby by elevator and exiting the gate; and the astonishing vision of the hotel toppling in slow motion over on the poor doorman after his demotion. And can you believe that first night cityscape with the driving rain was all constructed and shot INDOORS?

However, I must say there is an unfortunate message in this drama, that of the merciless German stereotype: fawning before authority and deriding weakness--humiliating the powerless, admiring, almost worshiping the powerful. This is shown by the doorman's vanity and puffed-up self-image, which hinges, it seems, on a splendid uniform and the deference it alone inspires. Position is everything to him, his family, employers, hotel guests and neighbors. This is a shallow world, indeed, a social mentality that I can imagine, without straining too much, easily leading in a few brief years straight to the all-too-successful Gestapo! (I would add that the ending seems to contradict this, but the ending must be discounted; it is a sheer fantasy, "tacked on," really unrelated to the rest of the film and completely out of character.)

Der Letzte Mann is nothing short of the epitome of viewing pleasure. Beautifully shot, the urban landscape in which a noble doorman earns his keep (and humanity) is throughout dream-like, infused with a decidedly ethereal quality. Added to a magical visual backdrop is a haunting musical score, highlighted by sweeping cello chords which cut straight to the heart. With regard to prominent themes, the picture speaks volumes about the fragility of human existence and, specifically, human dignity. The shallow and arbitrary nature of a society bent predominantly on the acquisition and elevation of pecuniary wealth, as well as the perseverance of the individual through it all, is illustrated masterfully through both the zenith and nadir of the doorman's existence, as documented in this truly excellent work of the interwar period.

Lo sapevi?

- QuizThe first "dolly" (a device that allows a camera to move during a shot) was created for this film. According to Edgar G. Ulmer, who worked on the film, the idea to make the first dolly came from the desire to focus on Emil Jannings' face during the first shot of the movie, as he moved through the hotel. They obviously didn't know how to make a dolly technically, so they created the first one out of a baby's carriage. They then pulled the carriage on a sort of railway that was built in the studio.

- BlooperWhen the porter comes home with the stolen coat, the third button down (which fell off earlier) is still there until a close-up of him at the door.

- Versioni alternativeThere is an Italian edition of this film on DVD, re-edited in double version (1.33:1 and 1.78:1) with the contribution of film historian Riccardo Cusin. This version is also available for streaming on some platforms.

- ConnessioniEdited into Germania nove zero (1991)

I più visti

Accedi per valutare e creare un elenco di titoli salvati per ottenere consigli personalizzati

- How long is The Last Laugh?Powered by Alexa

Dettagli

Botteghino

- Lordo Stati Uniti e Canada

- 94.812 USD

- Tempo di esecuzione1 ora 28 minuti

- Colore

- Mix di suoni

- Proporzioni

- 1.33 : 1

Contribuisci a questa pagina

Suggerisci una modifica o aggiungi i contenuti mancanti