IMDb रेटिंग

7.2/10

20 हज़ार

आपकी रेटिंग

इतालवी राजनेता गिउलिओ आंद्रेओटी की कहानी, जिन्होंने 1946 में, लोकतंत्र की बहाली के बाद से, सात बार इटली के प्रधानमंत्री के रूप में कार्य किया है.इतालवी राजनेता गिउलिओ आंद्रेओटी की कहानी, जिन्होंने 1946 में, लोकतंत्र की बहाली के बाद से, सात बार इटली के प्रधानमंत्री के रूप में कार्य किया है.इतालवी राजनेता गिउलिओ आंद्रेओटी की कहानी, जिन्होंने 1946 में, लोकतंत्र की बहाली के बाद से, सात बार इटली के प्रधानमंत्री के रूप में कार्य किया है.

- 1 ऑस्कर के लिए नामांकित

- 32 जीत और कुल 40 नामांकन

फ़ीचर्ड समीक्षाएं

I'm sure if I were raised in Italy and paid attention to Italian politics day in and day out all of what transpires in Il Divo would be no less than engrossing. The story of Androetti, the head of a government that went for seven administrations and then went on to run for President has some really fascinating things to it. One of those is seeing just how the parliament works in those scenes midway through the picture and how the country actually chooses its president, which is so far removed from the US democratic process it's hard to fathom. And I also admired how the actor playing Androetti so got into this kind of quietly conniving politician, a man who believed that politics was everything and yet would never get passionate enough to raise his voice above a whisper. Somewhere inside of him a Dick Cheney is rumbling, perhaps.

But the problem in watching the film if you don't pay attention to the Italian politics of the period, or just in general, is that the filmmakers lose you fairly quickly. I usually find myself a viewer who doesn't like to be spoon-fed information very simply, but this is on the opposite end of the cannon where only a few real details are clear enough and then the rest comes whizzing by at a quick clip (and quick indeed as the camera style is akin to the operatic nature of Scorsese, only not as talented or focused). Names of characters keep coming up as title cards, and except for a couple of names like "The Lemon" (Androetti's right-hand man), none of them really stick out, and the incidents keep piling up without any real connection. At some point the basic story does reveal itself and holds some interest, but there's a disconnect between many scenes too, and a sense of cross-cutting done a few times (i.e. the horse race scene crossed with a shooting) comes off as unimaginative.

It's not a waste of time though if you're totally ignorant about Italy's political structure and brash sense of the power dynamic. But it's not one that I particularly enjoyed, either, and its lack of a connection with the mounting details made it harder to appreciate.

But the problem in watching the film if you don't pay attention to the Italian politics of the period, or just in general, is that the filmmakers lose you fairly quickly. I usually find myself a viewer who doesn't like to be spoon-fed information very simply, but this is on the opposite end of the cannon where only a few real details are clear enough and then the rest comes whizzing by at a quick clip (and quick indeed as the camera style is akin to the operatic nature of Scorsese, only not as talented or focused). Names of characters keep coming up as title cards, and except for a couple of names like "The Lemon" (Androetti's right-hand man), none of them really stick out, and the incidents keep piling up without any real connection. At some point the basic story does reveal itself and holds some interest, but there's a disconnect between many scenes too, and a sense of cross-cutting done a few times (i.e. the horse race scene crossed with a shooting) comes off as unimaginative.

It's not a waste of time though if you're totally ignorant about Italy's political structure and brash sense of the power dynamic. But it's not one that I particularly enjoyed, either, and its lack of a connection with the mounting details made it harder to appreciate.

This is a film of two parts - something which a previous comment didn't really make clear - we see the events of Italy during Andreotti's reign in the first half from Andreoti's point of view: then in the second half we see the same events again from (depending on your perspective) either a more dispassionate or a more disparaging observation.

As a bit of cinema it is brilliant (one or two IMO rather silly unslick bits of special FX, just ignore them!) but altogether not to be missed. I doubt that it will translate well, and even for a seasoned appassionato of Italian politics the introduction of characters using (clever) superimposed text was flawed by the overshort screen time which these important notes were allowed.

As a bit of cinema it is brilliant (one or two IMO rather silly unslick bits of special FX, just ignore them!) but altogether not to be missed. I doubt that it will translate well, and even for a seasoned appassionato of Italian politics the introduction of characters using (clever) superimposed text was flawed by the overshort screen time which these important notes were allowed.

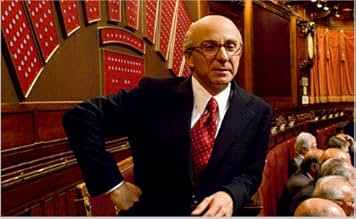

Il Divo, which won the Jury Prize at Cannes last year and has recently been released in US movie houses, is a devastatingly ironic and highly stylized portrait of the strange, extraordinarily powerful and long-lived Italian politician Giulio Andreotti. He has been in Italian government in some office or other since the late 1940's. After slipping out of repeated convictions for Mafia ties in the past decade he remains "senator for life" at the age of 90, and he's been credited with helping bring down governments even quite recently.

The ultimate political survivor, Andreotti was seven times prime minister from 1972 to 1992. He's had a seat in the Italian parliament without interruption since 1946, and has also been Defense Minister, Foreign Minister, and President. In Andreotti's own view (though he walked out on the film) his wife of 60 years Livia (Anna Bonaiuto) and his long-serving secretary Vincenza Enea (Piera Degli Esposti), are both sympathetically portrayed in Il Divo. He really didn't like being shown kissing Mafia boss Toto Riina, which he has said never happened. In the film, Andreotti is most haunted by the Red Brigades' murder of the kidnapped of Aldo Moro, which he might have prevented.

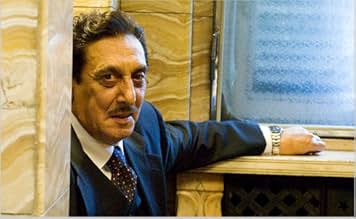

Though Sorrentino's film is in some ways a detailed chronicle of Anreotti's 60-plus years of political power and dubious dealings, with a focus on the seventh government and its aftermath, the film seems more an exercise in style than an impassioned study of politics. The self-consciousness of its frequent uses of loud contrasting music, ceremonial, almost Kabuuki-like set pieces, and slow-motion to muffle scenes of violence are further underlined by the performance of Toni Servillo, who accurately, perhaps too accuately, mimics Andreotti's look, his hunched posture, even his oddly turned-down ears, and his puppet-like mannerisms. Staring forward, neck rigid, he keeps his arms close to his body and his hands turned inward and peers expressionlessly out of his big eyeglasses. He walks across the floor in quick tiny steps like some 18th-century Japanese court lady. There is no attempt by director or principal actor to charm or to involve. It seems Sorrentino, with Servillo's diligent collaboration, is laughing not only at Andreotti and at Italian politics, but at us.

Il Divo is soulless and cynical, but it is so stylish that it's bound to be remembered. It's some kind of ultimate statement of the essence of the slick, heavily-guarded world of Italian political corruption. In its own special, magisterially mean-spirited and pessimistic way it's an instant classic.

In this film, Andreotti, who has been referred to as "Il divo Giulio" ("The God Giulio," referencing the Roman Empire's deification of Julius Caesar), and by monikers like "Beelzebub," "The Fox," "The Black Pope," "The Prince of Darkness," and "The Hunchback," is a queer, nerdy, mummified-looking creature who hardly ever changes expression or cracks a smile. His rigid gestures and the odd commentary of his group of primary supporters, themselves all provided with gangster-style nicknames, lead to a series of scenes that suggest politics as caricatural facade, as almost pure ritual, with time out on occasion for jokes, self-pity, and cruelty to others. You won't hear constituents mentioned in this movie, though when somebody says another politician prays to God but he prays to the priest, Andreotti answers: "Priests vote. God doesn't." Politics is everything to him, and politics means the pursuit of power.

For a non-Italian the details of various moments from the Aldo Moro kidnapping and all the terrorism of the Brigate Rosse of the 1970's to the 1990 Mafia trials may be pretty confusing. It's not that the filmmakers don't care; they're primarily talking to an Italian audience. But even for such an audience, they're keeping an ironic distance.

The facade never cracks. In one scene, typically staring straight forward, Andreotti delivers an impassioned speech of self-defense, raising his voice almost to a shout at the end, but without moving a muscle of his face. Servillo is a noted man of the theater in Italy and his whole performance is a chilly tour de force that inspires awe without giving much pleasure. Andreotti in this soliloquy--which highlights the film's often solipsistic feel--argues that a leader must manipulate evil in order to maintain good. This may fit in with the evidence that he collaborated with the Mafia, and yet at times was severe in repressing it.

In life as in this film Andreotti has compensated for what may be the lack of visible humanity by being a wit, and Il Divo crams as many of the famous battute or one-lineers into scenes as it can. One was "the trouble with the Pope is that he doesn't know the Vatican." Another: "They blame me for everything, except the Punic wars." "Signor Andreotti, how do you keep your conscience clean?" he was once asked. "I never use it," he replied. Other bons mots among many: "The trouble with the Red Brigades is they're too serious," and "Power is fatiguing only to those who don't have it." The world of Italian politics is baffling to the outsider. Andreotti's cool detachment and wit and this film's stylized cynicism may be the best approach to its deviousness and complexity.

Last year Servillo also played one of the main characters in Matteo Garrone's Gomorrah, where he's an out-and-out Mafia functionary. Gomorrah won Cannes' number-two award (just below the Golden Palm) the Grand Prize, last year, which given Il Divo's Jury Prize prompted declarations of a rebirth of Italian cinema in the making. Non-Italians like Mafia movies; Italians are sick of them, and might have wished for patriotic reasons that their best filmmakers had won applause by turning to some other subject matter. Both these films are cold, detached, and analytical. Maybe they mean Italians are getting serious about their own film industry and want to look the country's ugliest aspects right in the eye. But don't look for hope here. A great cinema requires more humanity than this.

The ultimate political survivor, Andreotti was seven times prime minister from 1972 to 1992. He's had a seat in the Italian parliament without interruption since 1946, and has also been Defense Minister, Foreign Minister, and President. In Andreotti's own view (though he walked out on the film) his wife of 60 years Livia (Anna Bonaiuto) and his long-serving secretary Vincenza Enea (Piera Degli Esposti), are both sympathetically portrayed in Il Divo. He really didn't like being shown kissing Mafia boss Toto Riina, which he has said never happened. In the film, Andreotti is most haunted by the Red Brigades' murder of the kidnapped of Aldo Moro, which he might have prevented.

Though Sorrentino's film is in some ways a detailed chronicle of Anreotti's 60-plus years of political power and dubious dealings, with a focus on the seventh government and its aftermath, the film seems more an exercise in style than an impassioned study of politics. The self-consciousness of its frequent uses of loud contrasting music, ceremonial, almost Kabuuki-like set pieces, and slow-motion to muffle scenes of violence are further underlined by the performance of Toni Servillo, who accurately, perhaps too accuately, mimics Andreotti's look, his hunched posture, even his oddly turned-down ears, and his puppet-like mannerisms. Staring forward, neck rigid, he keeps his arms close to his body and his hands turned inward and peers expressionlessly out of his big eyeglasses. He walks across the floor in quick tiny steps like some 18th-century Japanese court lady. There is no attempt by director or principal actor to charm or to involve. It seems Sorrentino, with Servillo's diligent collaboration, is laughing not only at Andreotti and at Italian politics, but at us.

Il Divo is soulless and cynical, but it is so stylish that it's bound to be remembered. It's some kind of ultimate statement of the essence of the slick, heavily-guarded world of Italian political corruption. In its own special, magisterially mean-spirited and pessimistic way it's an instant classic.

In this film, Andreotti, who has been referred to as "Il divo Giulio" ("The God Giulio," referencing the Roman Empire's deification of Julius Caesar), and by monikers like "Beelzebub," "The Fox," "The Black Pope," "The Prince of Darkness," and "The Hunchback," is a queer, nerdy, mummified-looking creature who hardly ever changes expression or cracks a smile. His rigid gestures and the odd commentary of his group of primary supporters, themselves all provided with gangster-style nicknames, lead to a series of scenes that suggest politics as caricatural facade, as almost pure ritual, with time out on occasion for jokes, self-pity, and cruelty to others. You won't hear constituents mentioned in this movie, though when somebody says another politician prays to God but he prays to the priest, Andreotti answers: "Priests vote. God doesn't." Politics is everything to him, and politics means the pursuit of power.

For a non-Italian the details of various moments from the Aldo Moro kidnapping and all the terrorism of the Brigate Rosse of the 1970's to the 1990 Mafia trials may be pretty confusing. It's not that the filmmakers don't care; they're primarily talking to an Italian audience. But even for such an audience, they're keeping an ironic distance.

The facade never cracks. In one scene, typically staring straight forward, Andreotti delivers an impassioned speech of self-defense, raising his voice almost to a shout at the end, but without moving a muscle of his face. Servillo is a noted man of the theater in Italy and his whole performance is a chilly tour de force that inspires awe without giving much pleasure. Andreotti in this soliloquy--which highlights the film's often solipsistic feel--argues that a leader must manipulate evil in order to maintain good. This may fit in with the evidence that he collaborated with the Mafia, and yet at times was severe in repressing it.

In life as in this film Andreotti has compensated for what may be the lack of visible humanity by being a wit, and Il Divo crams as many of the famous battute or one-lineers into scenes as it can. One was "the trouble with the Pope is that he doesn't know the Vatican." Another: "They blame me for everything, except the Punic wars." "Signor Andreotti, how do you keep your conscience clean?" he was once asked. "I never use it," he replied. Other bons mots among many: "The trouble with the Red Brigades is they're too serious," and "Power is fatiguing only to those who don't have it." The world of Italian politics is baffling to the outsider. Andreotti's cool detachment and wit and this film's stylized cynicism may be the best approach to its deviousness and complexity.

Last year Servillo also played one of the main characters in Matteo Garrone's Gomorrah, where he's an out-and-out Mafia functionary. Gomorrah won Cannes' number-two award (just below the Golden Palm) the Grand Prize, last year, which given Il Divo's Jury Prize prompted declarations of a rebirth of Italian cinema in the making. Non-Italians like Mafia movies; Italians are sick of them, and might have wished for patriotic reasons that their best filmmakers had won applause by turning to some other subject matter. Both these films are cold, detached, and analytical. Maybe they mean Italians are getting serious about their own film industry and want to look the country's ugliest aspects right in the eye. But don't look for hope here. A great cinema requires more humanity than this.

Giulio Andreotti can be seen as both the precursor to, and the antithesis of, Silvio Belusconi: an Italian politician with his fingers on every lever that led to power, accused of everything but convicted of nothing, and yet peculiarly devoid of conventional charisma. A sense of a particularity, of a man who had become nothing beyond a carefully constructed defence of his own behaviour, was nicely captured in Tim Parks' fictional work 'Destiny'; and we get the same feeling in 'Il Divo', a biopic with an extraordinary performance Toni Sevillo by in the lead role. What neither offer is definitive, or even speculative, resolution of the enigma and his actions; just a chilling yet plausible portrait of the man. Yet without providing clear answers, something else must provide the story. In Parks' book, Andreotti was a bit part; in the film, there's no other narrative, and sometimes the direction feels a little too heavy, overdone perhaps because there isn't a smooth tale holding things together. And the music on the soundtrack seems deliberately incongruous, thrown into the mix to provide some variation in tone that would otherwise have been lacking. But Servillo's performance more than compensates; it will lead you wanting the same answers, one suspects, that everyone has wanted from Andreotti for a long long time.

A film to admire but impossible to love. Not an ounce of humanity to cling on to. Splendidly put together but only with the intellect so, for non Italians a puzzle that seems like a figment of someone's imagination and to be taken as a sort of intellectual metaphor. How can a creature from hell in good terms with the Catholic Church can survive all this years and when I say survive I mean survive from every possible angle. Italians know that is not only true but normal. I'm half Italian so I know what I'm talking about. Andreotti is played by Paolo Servillo in a performance that is part caricature, part faithful portrait, a work of genius and I suspect that the slightly surreal, grotesque undertones, allowed the movie to be made and succeed in the way it did, at least in Italy. I saw it in New York where I was the only spectator in the theater. I can't wait to see where director Sorrentino will take us next.

क्या आपको पता है

- ट्रिवियाThe first cut of the movie was 145-minute long.

- भाव

Giulio Andreotti: I know I am an average man but looking around I do not see any giant.

- क्रेज़ी क्रेडिटEnd credits features the following dedication: "per Daniela, che mi ha salvato" ("for Daniela, who saved me"). Daniela D'Antonio is Paolo Sorrentino's wife.

- कनेक्शनFeatured in The 82nd Annual Academy Awards (2010)

- साउंडट्रैकLa prima cosa bella

Written by Mogol, Gian Piero Reverberi and Nicola Di Bari

Performed by Ricchi e Poveri

Published by Universal Music Publishing Ricordi S.r.l.

Courtesy of EMi Music Italy S.p.a.

टॉप पसंद

रेटिंग देने के लिए साइन-इन करें और वैयक्तिकृत सुझावों के लिए वॉचलिस्ट करें

- How long is Il Divo?Alexa द्वारा संचालित

विवरण

बॉक्स ऑफ़िस

- बजट

- €57,00,000(अनुमानित)

- US और कनाडा में सकल

- $2,40,159

- US और कनाडा में पहले सप्ताह में कुल कमाई

- $13,867

- 26 अप्रैल 2009

- दुनिया भर में सकल

- $1,12,60,366

- चलने की अवधि

- 1 घं 50 मि(110 min)

- रंग

- ध्वनि मिश्रण

- पक्ष अनुपात

- 2.35 : 1

इस पेज में योगदान दें

किसी बदलाव का सुझाव दें या अनुपलब्ध कॉन्टेंट जोड़ें