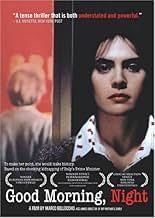

Buongiorno, notte

- 2003

- 1 घं 46 मि

IMDb रेटिंग

7.1/10

4.2 हज़ार

आपकी रेटिंग

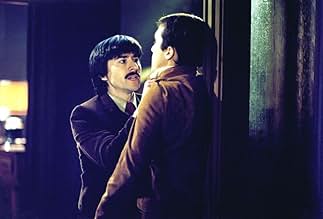

अपनी भाषा में प्लॉट जोड़ेंThe 1978 kidnapping of politician Aldo Moro as seen from the perspective of one of his assailants: a conflicted young woman in the ranks of the Red Brigade.The 1978 kidnapping of politician Aldo Moro as seen from the perspective of one of his assailants: a conflicted young woman in the ranks of the Red Brigade.The 1978 kidnapping of politician Aldo Moro as seen from the perspective of one of his assailants: a conflicted young woman in the ranks of the Red Brigade.

- पुरस्कार

- 13 जीत और कुल 21 नामांकन

Giulio Bosetti

- Paolo VI

- (as Giulio Stefano Bosetti)

फ़ीचर्ड समीक्षाएं

The events bookending this movie are true, but the actual story is pure speculation...thus leaving the door wide open for the storytelling.

Communist Catholics are an oddity...the contradictions in that appellation alone are manifest. So what we have here is told somewhat in the manner of a Passion Play, cross-pollinated with a critique vs. defense of the Marx-Hegel "Holy Family"...the argument centers on the captive's immediate concern about execution, whereas the captors insist on demonstrating they are merciless.

The problem is, all of this seems to be going on as if there's no outside world of concern...oh, we get leakage in from TV and newspapers, but no sense that Rome is under lockdown. This ends up totally alienated from the central symbolism (Mora's body having been found precisely halfway between the respective Christian Democrats' and Italian Communist Party's headquarters). We're locked behind the writing (the stacks of books, and simultaneously, Chiara within the library), then left for dead with no spatial, political or symbolic context.

That said, there is some cleverness in the limitation placed on Chiara, who is the only one who can tell the story outside the apartment, but has a proximity barrier from the writer at the cubicle door and peephole. Upon reaching perigee, she is reduced to defiant tears. Note also how she dreams in Soviet-era propaganda films!

Communist Catholics are an oddity...the contradictions in that appellation alone are manifest. So what we have here is told somewhat in the manner of a Passion Play, cross-pollinated with a critique vs. defense of the Marx-Hegel "Holy Family"...the argument centers on the captive's immediate concern about execution, whereas the captors insist on demonstrating they are merciless.

The problem is, all of this seems to be going on as if there's no outside world of concern...oh, we get leakage in from TV and newspapers, but no sense that Rome is under lockdown. This ends up totally alienated from the central symbolism (Mora's body having been found precisely halfway between the respective Christian Democrats' and Italian Communist Party's headquarters). We're locked behind the writing (the stacks of books, and simultaneously, Chiara within the library), then left for dead with no spatial, political or symbolic context.

That said, there is some cleverness in the limitation placed on Chiara, who is the only one who can tell the story outside the apartment, but has a proximity barrier from the writer at the cubicle door and peephole. Upon reaching perigee, she is reduced to defiant tears. Note also how she dreams in Soviet-era propaganda films!

Based on a novel, the film describes the situation of Aldo Moro during his captivity. There is more than a meticulous realistic point of view given in this film : it tries to figure thoughts and attitudes of the kidnappers, members of brigate rosse. It explores the contradictions of hidden activists who are desperately trying to justify violent actions by the salvation of proletariat and rise of a social justice. They are seen in their loneliness, especially on the affective, emotional side. The psycho-rigidity of their mind is patent, not only in the sententious talks to their prisoner, in a certain desperate naivety to seek echos of their action in public opinion throughout medias, but also in the way they rule relationships. It's not politically that Moro's character strongly opposes to his kidnappers' characters, but rather in the way he's emotionnaly tied to his family (although being a prisonner, he can write letters), while the others seem alienated facing their own families (Mariano pretends to have cut any link to his son, Chiara tries to avoid familial phone calls and meetings, another member is mad about being away of his girl and suffers to be away from her mind and point of view when he sees her). Together, those members don't look like a family of a new kind. Maybe is it the main limit of Bellochio's movie, not to explore the way such an internal and autistic logical builds inside radical groups. But the movie spots a clearly defined place and time, focusing exclusively on elements linked to Moro's detention in a casual apartment (the gunfight of the kidnapping and then the death of the prisonner are seen indirectly throughout television). The strength of the movie is to develop a symbolic aspect with the character of Chiara's colleague (of her cover work) who defends imagination against the brutality of autocratic arbitrary. Almost fantastically, this character seems to guess Chiara's situation, writing a fiction about the events (like the movie we're effectively seeing as spectators) and modifying her feelings : when she realizes how any execution is horrible and unfair (reminding executions of italian partisani of WWII), it's too late and there is no other escape than in her own imagination (dream-like scene that the film also shows us). I believe it's a good and clever way to introduce us into such a historical event (maybe still wounding italian society), imagination. I also like the aspects and details of the movie that describe the importance of christianity in the conscience of the italians (even marxists ones, subconsciously) and critizises the sacrificial consensus into a falsely ineluctable execution but real murder.

I've read the other comments on this board and I would like to precise that Aldo Moro at the time was not the Italian President and that obviously the Red Brigades were out for his blood because he was working skilfully at a compromise between the Christian Democrats and the Communists and that meant for the extremists of the left to be cut out from any kind of power or hold they might have on the Government. The film itself does not seek to give political answers and is much more concerned with the human aspects of the drama. It's more lyrical than realistic... if you're looking for action or for a docudrama, you should probably go elsewhere.

I won't comment on the film's artistic merits, which I regard as noteworthy, nor on the psychological portrait given of the brigatisti, which I thought interesting but flawed. I will only say that the film was deeply moving for me and had me crying uncontrollably at times. I wish to give, instead, a sketch of the film's political context for the benefit of those whose familiarity with that period in Italian politics may be limited.

By 1978 Italy had been ruled uninterruptedly for more than 30 years by coalition governments, all of which were dominated by the Christian-Democratic party (DC). The Italian Communist Party (PCI) had been thrown out of the government in 1947 (in part, on the insistence of Washington as a condition for Italy's receiving Marshall aid monies), and it was excluded from all governments even though its share of the popular vote rose with every post-war election, making it the second largest party in Italy (it peaked at more than a third of the vote in the late 1970s). The PCI was not your average Communist party. It espoused a route to the transformation of capitalism that emphasized gradualism, social mobilization, and electoral politics--and by the early '60s its commitment to the acceptance of the principles of democratic pluralism was public and pronounced. By the end of the '70s, Italy was sorely in need of reform--the kind of reform in institutional arrangements and socio-economic policies that could only come through a change in government.

The 30 years of DC rule had created a regime rent through and through with corruption and unresponsive government (by contrast with the regional governments run by the PCI, which were models of efficiency and responsive government). But the US and most of the DC continued to argue that the opposition should not be allowed to come to power under any circumstances because of the "Communist menace."

Aldo Moro, president of the DC at the time, was one of a few DC leaders receptive to the idea of bringing the PCI into the government to effect reforms and make the country more governable--responding, as he was, to the initiative of Enrico Berlinguer, leader of the PCI, who called for an "historic compromise" with the Catholic masses and their party. But at the same time that the PCI was inching towards the government, there were fractions of the left in Italy that felt that the PCI was selling out the dream of making "The Revolution". Certainly it was true that the PCI had long abandoned the notion of "Revolution in the West" as resembling anything like the storming of the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg in 1917 (note the imagery of revolutionary Russia thrown into the film by Bellocchio as representative of the consciousness of the brigatisti). But the PCI continued to be nominally wedded to the idea that capitalism was not the final resting place in the evolution of human social-economic systems, and that it could and should be replaced by a system of production based on production to satisfy human needs rather than private profit.

The closer the PCI moved towards government and compromise with the DC, the more this commitment to a socio-economic order alternative to capitalism was put into question in the eyes of Italy's "revolutionary" left (all of which, by the way,existed outside of the PCI in other social and political organizations).

Enter the Red Brigades (BR). Most of the their ranks were filled with leftists who came to "revolutionary" politics via Catholicism and the social gospel. They believed themselves to be heirs to the tradition of revolutionary militancy (and armed struggle)embodied in the Resistenza, the struggle against the German occupation of Italy,1943-45--a struggle which, in the minds of many of the combatants, was waged for the sake of a socio-economic order alternative to the inequalities and irrationalities of capitalism (it was mainly Bellocchio's use of clips showing the execution of "partigiani" (resistance fighters) and the reading of the letters they had written just prior to their execution which brought me to tears).

The BR believed that through "exemplary" actions (the knee-capping or killing of politicians, journalists, and trade-unionists seen by them as enemies of the working class) they might be able to galvanize the masses of the working class, whose revolutionary militancy had, presumably, had been lulled into a quiescent state by the "sell-out" leadership of the PCI.

The kidnapping of Moro was designed to put a stop to that process, and indeed it succeeded well. To the delight both of the "revolutionary" left and Washington the PCI was kept out of the government for almost another 20 years, until after the fall of the USSR and the complete dissolution of the DC under the weight of a gigantic scandal. One side note: Bellocchio is certainly in error in suggesting that Stalin would have been part of the fantasies of the BR--while they greatly admired Lenin for having pulled off the Bolshevik Revolution, they detested Stalin and the bureaucratized party rule that came in his wake.

One final note: I'm not sure I understand why Bellocchio has chosen as his counter-hero a figure who suggests the use of "fantasia" as an alternative to violence. It was precisely the BR's "flight of imagination" that got them into trouble, imagining a world that didn't exist in Italy--a world of revolutionary seething masses just waiting for a spark to ignite them. In politics there's no substitute for Machiavelli's "chiaroveggenza" (the capacity to see things clearly).

By 1978 Italy had been ruled uninterruptedly for more than 30 years by coalition governments, all of which were dominated by the Christian-Democratic party (DC). The Italian Communist Party (PCI) had been thrown out of the government in 1947 (in part, on the insistence of Washington as a condition for Italy's receiving Marshall aid monies), and it was excluded from all governments even though its share of the popular vote rose with every post-war election, making it the second largest party in Italy (it peaked at more than a third of the vote in the late 1970s). The PCI was not your average Communist party. It espoused a route to the transformation of capitalism that emphasized gradualism, social mobilization, and electoral politics--and by the early '60s its commitment to the acceptance of the principles of democratic pluralism was public and pronounced. By the end of the '70s, Italy was sorely in need of reform--the kind of reform in institutional arrangements and socio-economic policies that could only come through a change in government.

The 30 years of DC rule had created a regime rent through and through with corruption and unresponsive government (by contrast with the regional governments run by the PCI, which were models of efficiency and responsive government). But the US and most of the DC continued to argue that the opposition should not be allowed to come to power under any circumstances because of the "Communist menace."

Aldo Moro, president of the DC at the time, was one of a few DC leaders receptive to the idea of bringing the PCI into the government to effect reforms and make the country more governable--responding, as he was, to the initiative of Enrico Berlinguer, leader of the PCI, who called for an "historic compromise" with the Catholic masses and their party. But at the same time that the PCI was inching towards the government, there were fractions of the left in Italy that felt that the PCI was selling out the dream of making "The Revolution". Certainly it was true that the PCI had long abandoned the notion of "Revolution in the West" as resembling anything like the storming of the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg in 1917 (note the imagery of revolutionary Russia thrown into the film by Bellocchio as representative of the consciousness of the brigatisti). But the PCI continued to be nominally wedded to the idea that capitalism was not the final resting place in the evolution of human social-economic systems, and that it could and should be replaced by a system of production based on production to satisfy human needs rather than private profit.

The closer the PCI moved towards government and compromise with the DC, the more this commitment to a socio-economic order alternative to capitalism was put into question in the eyes of Italy's "revolutionary" left (all of which, by the way,existed outside of the PCI in other social and political organizations).

Enter the Red Brigades (BR). Most of the their ranks were filled with leftists who came to "revolutionary" politics via Catholicism and the social gospel. They believed themselves to be heirs to the tradition of revolutionary militancy (and armed struggle)embodied in the Resistenza, the struggle against the German occupation of Italy,1943-45--a struggle which, in the minds of many of the combatants, was waged for the sake of a socio-economic order alternative to the inequalities and irrationalities of capitalism (it was mainly Bellocchio's use of clips showing the execution of "partigiani" (resistance fighters) and the reading of the letters they had written just prior to their execution which brought me to tears).

The BR believed that through "exemplary" actions (the knee-capping or killing of politicians, journalists, and trade-unionists seen by them as enemies of the working class) they might be able to galvanize the masses of the working class, whose revolutionary militancy had, presumably, had been lulled into a quiescent state by the "sell-out" leadership of the PCI.

The kidnapping of Moro was designed to put a stop to that process, and indeed it succeeded well. To the delight both of the "revolutionary" left and Washington the PCI was kept out of the government for almost another 20 years, until after the fall of the USSR and the complete dissolution of the DC under the weight of a gigantic scandal. One side note: Bellocchio is certainly in error in suggesting that Stalin would have been part of the fantasies of the BR--while they greatly admired Lenin for having pulled off the Bolshevik Revolution, they detested Stalin and the bureaucratized party rule that came in his wake.

One final note: I'm not sure I understand why Bellocchio has chosen as his counter-hero a figure who suggests the use of "fantasia" as an alternative to violence. It was precisely the BR's "flight of imagination" that got them into trouble, imagining a world that didn't exist in Italy--a world of revolutionary seething masses just waiting for a spark to ignite them. In politics there's no substitute for Machiavelli's "chiaroveggenza" (the capacity to see things clearly).

The true story of the kidnap of Italian political leader Aldo Moro by the Red Brigades in 1978 is turned into a haunting, disturbing tone poem of s film.

Eschewing realism, or the obvious tense, linear approach, this focuses on the experience through the eyes of one the young kidnappers, and her ever growing doubts about the righteousness of the mission. But rather than express this literally, we see it emerge in dream sequences, and behind her eyes.

Beautifully shot, with a terrific use of classical and modern music (Pink Floyd shows up more than once) this quiet nightmare of a film is far more effecting and thought provoking than most political dramas. It does not miss the irony that Aldo was a humanist who was actually inviting the communist party to be part of the government.

A great cautionary truth based fable about the danger of giving yourself completely and unquestioningly to any ideology, left or right, religious or secular.

Eschewing realism, or the obvious tense, linear approach, this focuses on the experience through the eyes of one the young kidnappers, and her ever growing doubts about the righteousness of the mission. But rather than express this literally, we see it emerge in dream sequences, and behind her eyes.

Beautifully shot, with a terrific use of classical and modern music (Pink Floyd shows up more than once) this quiet nightmare of a film is far more effecting and thought provoking than most political dramas. It does not miss the irony that Aldo was a humanist who was actually inviting the communist party to be part of the government.

A great cautionary truth based fable about the danger of giving yourself completely and unquestioningly to any ideology, left or right, religious or secular.

क्या आपको पता है

- ट्रिवियाWas appreciated by the relatives of Aldo Moro.

- गूफ़Near the end, when Aldo Moro walks away in the deserted street, you can see a multicolored Peace flag in the background. Those flags would decorate Italian streets only in 2003, to oppose the invasion of Iraq.

- साउंडट्रैकMarcia trionfale

(from "Aida")

Composed by Giuseppe Verdi

Performed by Orchestra e Coro del Teatro dell'Opera di Roma

Conducted by Georg Solti

Decca Records, 1962

टॉप पसंद

रेटिंग देने के लिए साइन-इन करें और वैयक्तिकृत सुझावों के लिए वॉचलिस्ट करें

- How long is Good Morning, Night?Alexa द्वारा संचालित

विवरण

- रिलीज़ की तारीख़

- कंट्री ऑफ़ ओरिजिन

- भाषा

- इस रूप में भी जाना जाता है

- Good Morning, Night

- उत्पादन कंपनियां

- IMDbPro पर और कंपनी क्रेडिट देखें

बॉक्स ऑफ़िस

- US और कनाडा में सकल

- $10,093

- US और कनाडा में पहले सप्ताह में कुल कमाई

- $2,769

- 13 नव॰ 2005

- दुनिया भर में सकल

- $42,40,918

- चलने की अवधि

- 1 घं 46 मि(106 min)

- रंग

- ध्वनि मिश्रण

- पक्ष अनुपात

- 1.66 : 1

इस पेज में योगदान दें

किसी बदलाव का सुझाव दें या अनुपलब्ध कॉन्टेंट जोड़ें