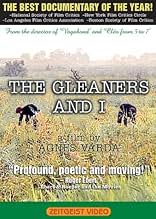

IMDb रेटिंग

7.7/10

9.6 हज़ार

आपकी रेटिंग

अपनी भाषा में प्लॉट जोड़ेंVarda films and interviews gleaners in France in all forms, from those picking fields after the harvest to those scouring the dumpsters of Paris.Varda films and interviews gleaners in France in all forms, from those picking fields after the harvest to those scouring the dumpsters of Paris.Varda films and interviews gleaners in France in all forms, from those picking fields after the harvest to those scouring the dumpsters of Paris.

- पुरस्कार

- 16 जीत और कुल 3 नामांकन

फ़ीचर्ड समीक्षाएं

You may remember director Agnès Varda from her 1986 film, VAGABOND. But over the last five decades, the `grandmother of French New Wave' has completed 29 other works, most showing her affection, bemusement, outrage, and wide-ranging curiosity for humanity.

Varda's most recent effort-the first filmed with a digital videocamera-focuses on gleaners, those who gather the spoils left after a harvest, as well as those who mine the trash. Some completely exist on the leavings; others turn them into art, exercise their ethics, or simply have fun. The director likens gleaning to her own profession-that of collecting images, stories, fragments of sound, light, and color.

In this hybrid of documentary and reflection, Varda raises a number of philosophical questions. Has the bottom line replaced our concern with others' well-being, even on the most essential level of food? What happens to those who opt out of our consumerist society? And even, What constitutes--or reconstitutes--art?

Along this road trip, she interviews plenty of French characters. We meet a man who has survived almost completely on trash for 15 years. Though he has a job and other trappings, for him it is `a matter of ethics.' Another, who holds a master's degree in biology, sells newspapers and lives in a homeless shelter, scavenges food from market, and spends his nights teaching African immigrants to read and write.

Varda is an old hippie, and her sympathies clearly lie with such characters who choose to live off the grid. She takes our frenetically consuming society to task and suggests that learning how to live more simply is vital to our survival.

At times we can almost visualize her clucking and wagging her finger-a tad heavy-handedly advancing her agenda. However, the sheer waste of 25 tons of food at a clip is legitimately something to cluck about. And it is her very willingness to make direct statements and NOT sit on the fence that Varda fans most enjoy, knowing that her indignation is deeply rooted in her love of humanity.

The director interjects her playful humor as well-though it's subtle, French humor that differs widely from that of, say, Tom Green. Take the judge in full robes who stands in a cabbage field citing the legality of gleaning chapter and verse.

Quirky and exuberant, Varda, 72, is at an age where she's more concerned with having fun with her craft than impressing anyone. With her handheld digital toy, she pans around her house and pauses to appreciate a patch of ceiling mold. When she later forgets to turn off her camera, she films `the dance of the lens cap.'

One of the picture's undercurrents is the cycle of life-growth, harvest, decay. She often films her wrinkled hands and speaks directly about her aging process, suggesting that her own mortality is much on her mind. The gleaners pluck the fruits before their decay, as Varda lives life to the fullest, defying the inevitability of death. Toward the movie's end, she salvages a Lucite clock with no hands. As she films her face passing behind it, she notes, `A clock with no hands is my kind of thing.'

If you'd be the first to grab a heart-shaped potato from the harvest, or make a pile of discarded dolls into a totem pole, THE GLEANERS is probably your kind of thing.

Varda's most recent effort-the first filmed with a digital videocamera-focuses on gleaners, those who gather the spoils left after a harvest, as well as those who mine the trash. Some completely exist on the leavings; others turn them into art, exercise their ethics, or simply have fun. The director likens gleaning to her own profession-that of collecting images, stories, fragments of sound, light, and color.

In this hybrid of documentary and reflection, Varda raises a number of philosophical questions. Has the bottom line replaced our concern with others' well-being, even on the most essential level of food? What happens to those who opt out of our consumerist society? And even, What constitutes--or reconstitutes--art?

Along this road trip, she interviews plenty of French characters. We meet a man who has survived almost completely on trash for 15 years. Though he has a job and other trappings, for him it is `a matter of ethics.' Another, who holds a master's degree in biology, sells newspapers and lives in a homeless shelter, scavenges food from market, and spends his nights teaching African immigrants to read and write.

Varda is an old hippie, and her sympathies clearly lie with such characters who choose to live off the grid. She takes our frenetically consuming society to task and suggests that learning how to live more simply is vital to our survival.

At times we can almost visualize her clucking and wagging her finger-a tad heavy-handedly advancing her agenda. However, the sheer waste of 25 tons of food at a clip is legitimately something to cluck about. And it is her very willingness to make direct statements and NOT sit on the fence that Varda fans most enjoy, knowing that her indignation is deeply rooted in her love of humanity.

The director interjects her playful humor as well-though it's subtle, French humor that differs widely from that of, say, Tom Green. Take the judge in full robes who stands in a cabbage field citing the legality of gleaning chapter and verse.

Quirky and exuberant, Varda, 72, is at an age where she's more concerned with having fun with her craft than impressing anyone. With her handheld digital toy, she pans around her house and pauses to appreciate a patch of ceiling mold. When she later forgets to turn off her camera, she films `the dance of the lens cap.'

One of the picture's undercurrents is the cycle of life-growth, harvest, decay. She often films her wrinkled hands and speaks directly about her aging process, suggesting that her own mortality is much on her mind. The gleaners pluck the fruits before their decay, as Varda lives life to the fullest, defying the inevitability of death. Toward the movie's end, she salvages a Lucite clock with no hands. As she films her face passing behind it, she notes, `A clock with no hands is my kind of thing.'

If you'd be the first to grab a heart-shaped potato from the harvest, or make a pile of discarded dolls into a totem pole, THE GLEANERS is probably your kind of thing.

The Gleaners and I is odd in that it hardly feels like a proper film at all: it's shot on visibly cheap MiniDV, its editing is consistently unpolished, and it delights in crossing the line from personal to indulgent in excess. It's obvious that these are all deliberate choices; the question is, would we care if it didn't have the name Agnès Varda on it?

Ultimately, the film's amateurish style is somewhat deceptive: Varda demonstrates her talent for finding significance in the mundane, and strikes a number of compelling parallels in her examination of scavenger culture. The film does tend to coast on Varda's legendary new wave status at times, particularly as we linger on interviews and segments only tenuously related to the film's subject, but it's interesting as an example of a living legend embracing her medium's democratization: for all the good and bad it implies, she blends in seamlessly with the millions of talented people who own camcorders. -TK 10/21/10

Ultimately, the film's amateurish style is somewhat deceptive: Varda demonstrates her talent for finding significance in the mundane, and strikes a number of compelling parallels in her examination of scavenger culture. The film does tend to coast on Varda's legendary new wave status at times, particularly as we linger on interviews and segments only tenuously related to the film's subject, but it's interesting as an example of a living legend embracing her medium's democratization: for all the good and bad it implies, she blends in seamlessly with the millions of talented people who own camcorders. -TK 10/21/10

Jean Francois Millet, the French painter of the Barbizon school, seems to have been the inspiration for Agnes Varda's interesting documentary "Les glaneurs et la glaneuse". In fact, Ms. Varda makes it a point to take us along to the French countryside where Millet got the inspiration for his masterpiece "Les Glaneurs". Like in his other paintings, Millet comments about the peasantry working the fields in most of his canvases. One can see the poverty in his subjects as they struggle to gather crops for their employers.

Ms. Varda takes a humanistic approach to another type of activity in which she bases her story. In fact, the people one sees in the film are perhaps the descendants of the gleaners of Millet's time, except they are bringing whatever is left behind once the machinery takes care of gathering the best of each crop, leaving the rest to rot in the fields.

Agnes Varda takes a trip through her native France to show us the inequality of a system that produces such excesses that a part of it has to be dumped because it doesn't meet standards. On the one hand, there is such abundance, and on the other, one sees how some of the poor people showcased in the documentary can't afford to buy the basics and must resort to take it on their own to get whatever has been left in order to survive.

With this documentary, Agnes Varda shows an uncanny understanding to the problems most of these people are facing.

Ms. Varda takes a humanistic approach to another type of activity in which she bases her story. In fact, the people one sees in the film are perhaps the descendants of the gleaners of Millet's time, except they are bringing whatever is left behind once the machinery takes care of gathering the best of each crop, leaving the rest to rot in the fields.

Agnes Varda takes a trip through her native France to show us the inequality of a system that produces such excesses that a part of it has to be dumped because it doesn't meet standards. On the one hand, there is such abundance, and on the other, one sees how some of the poor people showcased in the documentary can't afford to buy the basics and must resort to take it on their own to get whatever has been left in order to survive.

With this documentary, Agnes Varda shows an uncanny understanding to the problems most of these people are facing.

1) Agnes Varda doesn't care that the quality of her digital camera is low; on the contrary, she loves is and is fascinated by how it captures things like her own hand (which she calls a "horror," which may or may not be a joke), and that love I think transfers to the audience. Anyway, her editing shows that this new digital quality gives more opportunities to capture life and images in exciting, vivid timing.

2) Gleaning isnt as inherently interesting as the people Varda talks to... At least that was my impression at first. And she talks to many of then. And guess what? These people, who vary from being old (and young) professionals to the destitute to old pros at this (even if theyre amateurs, specially if theyre amateurs), are so wholly rich and absorbing to watch that one realizes any filmmaker can make anything interesting so long as the subject matter connects. Varda connects with people, and art and with objects like potatoes and grapes and oysters and of course cats, and you feel that connection in your bones (if you're open to this, and Id fear meeting someone who was bored by this).

3) those rap songs are wondrous.

4) Varda wisely keeps her mistakes in - at one point while in a field she left her camera on and got a "dance" of a lens cap in front of her frame. Hey, why not put in a jazz track for a moment? And why put this in a movie about cleaning? Why not? Varda is all about the chances of life that happen in front of her (even finding a painting with gleaners while looking for something else). In a way this lends itself to what the film might really be about which is how people find joy in what they do. It might be stopping over to get things off the ground (and it may not be in a field, it may be more urban), or it may be filmmaking itself, which happens to be what Varda does (a curious point is when she meets someone whos a descendant of an early pioneer of cinema, ill leave it at that for you to see more).

5) If you are looking for this be about more concrete things, Varda has you covered too as there's the legal matters of gleaning and how it has been, how to say it, kindly outlawed in some parts of France (that is, some farmers dont want to see it gone, but that's the way it is). She even talks to legal officials - one in a field, naturally - and looks at a case of some kids tossing over trash cans. In this film, of course, it's not simply only about the joy or passion or even the compulsion of gleaning off fields, but waste and trash itself: how do we throw things out as a society and are okay with that? Can things that are discarded be reused, as clothes, as food, or even as art?

We may/are all be connected through what we throw out and what can be saved, which is a lot, and the difference is in who finds value in it or not. These people do, and Varda finds empathy, or at least wants us to. So while there's the legal questions, there's the real-world applications too. Theres politics underlying those who glean in rural places and those in the cities, but it's not too explicit. Just showing people picking through trash and leftovers is enough, because... Dont we all do it?

6) I continue to lament how much Varda I haven't seen till now.

2) Gleaning isnt as inherently interesting as the people Varda talks to... At least that was my impression at first. And she talks to many of then. And guess what? These people, who vary from being old (and young) professionals to the destitute to old pros at this (even if theyre amateurs, specially if theyre amateurs), are so wholly rich and absorbing to watch that one realizes any filmmaker can make anything interesting so long as the subject matter connects. Varda connects with people, and art and with objects like potatoes and grapes and oysters and of course cats, and you feel that connection in your bones (if you're open to this, and Id fear meeting someone who was bored by this).

3) those rap songs are wondrous.

4) Varda wisely keeps her mistakes in - at one point while in a field she left her camera on and got a "dance" of a lens cap in front of her frame. Hey, why not put in a jazz track for a moment? And why put this in a movie about cleaning? Why not? Varda is all about the chances of life that happen in front of her (even finding a painting with gleaners while looking for something else). In a way this lends itself to what the film might really be about which is how people find joy in what they do. It might be stopping over to get things off the ground (and it may not be in a field, it may be more urban), or it may be filmmaking itself, which happens to be what Varda does (a curious point is when she meets someone whos a descendant of an early pioneer of cinema, ill leave it at that for you to see more).

5) If you are looking for this be about more concrete things, Varda has you covered too as there's the legal matters of gleaning and how it has been, how to say it, kindly outlawed in some parts of France (that is, some farmers dont want to see it gone, but that's the way it is). She even talks to legal officials - one in a field, naturally - and looks at a case of some kids tossing over trash cans. In this film, of course, it's not simply only about the joy or passion or even the compulsion of gleaning off fields, but waste and trash itself: how do we throw things out as a society and are okay with that? Can things that are discarded be reused, as clothes, as food, or even as art?

We may/are all be connected through what we throw out and what can be saved, which is a lot, and the difference is in who finds value in it or not. These people do, and Varda finds empathy, or at least wants us to. So while there's the legal questions, there's the real-world applications too. Theres politics underlying those who glean in rural places and those in the cities, but it's not too explicit. Just showing people picking through trash and leftovers is enough, because... Dont we all do it?

6) I continue to lament how much Varda I haven't seen till now.

The French film Les glaneurs et la glaneuse was shown in the U.S. as The Gleaners & I (2000). It was written and directed by Agnès Varda,

Varda is a fascinating figure in the history of French filmmaking. Although she was making movies in France in the 60's, she wasn't actually a member of the French New Wave. Instead, Varda was part of a loosely joined group of directors that also included Alain Resnais and Chris Marker. (Although theoreticians place them into a group, Resnais said, "It is true that we are always ranked together, but what can you say we share apart from cats?") In any event Varda has a secure place in the history of French filmaking.

The Gleaners is a movie about people who survive by searching for food or objects that others don't want, or, at least, don't want to work to find. In the country, gleaners find fruits and vegetables that remain after the harvest has been completed. In the cities they scavenge for food that has been thrown out as garbage, or that has been left behind when the vegetable markets close. They also claim discarded furniture and appliances for repair and resale.

Whether by choice or by necessity, gleaners do their work at the fringes of the society. What they do isn't illegal, but it's not exactly mainstream either. However, this doesn't mean that the gleaners don't have their own fascinating personalities and informal codes of conduct.

Varda interviews gleaners in both rural and urban areas. What she learns--as do we--is that they are very skilled at--and often proud of--what they do. As Varda shows us, it takes skill and knowledge to survive as a gleaner. You have to know where to look and when to look to get enough to eat, or to sell. The gleaners are interesting individuals, and they're happy to talk about what they do. Varda has taken what they told her, and fashioned it into a fascinating movie.

The irony of this is clear when you look at the French title of the movie. The film is about gleaners, but it's also about one gleaner--Agnès Varda. Varda uses the bits and pieces offered to her by the gleaners, and fashions them into a movie. So, in that sense, she herself is the ultimate gleaner.

We saw the film on the large screen at Rochester's Dryden Theatre, as part of the excellent Rochester Labor Film Festival. However, it should also work on DVD.

Varda is a fascinating figure in the history of French filmmaking. Although she was making movies in France in the 60's, she wasn't actually a member of the French New Wave. Instead, Varda was part of a loosely joined group of directors that also included Alain Resnais and Chris Marker. (Although theoreticians place them into a group, Resnais said, "It is true that we are always ranked together, but what can you say we share apart from cats?") In any event Varda has a secure place in the history of French filmaking.

The Gleaners is a movie about people who survive by searching for food or objects that others don't want, or, at least, don't want to work to find. In the country, gleaners find fruits and vegetables that remain after the harvest has been completed. In the cities they scavenge for food that has been thrown out as garbage, or that has been left behind when the vegetable markets close. They also claim discarded furniture and appliances for repair and resale.

Whether by choice or by necessity, gleaners do their work at the fringes of the society. What they do isn't illegal, but it's not exactly mainstream either. However, this doesn't mean that the gleaners don't have their own fascinating personalities and informal codes of conduct.

Varda interviews gleaners in both rural and urban areas. What she learns--as do we--is that they are very skilled at--and often proud of--what they do. As Varda shows us, it takes skill and knowledge to survive as a gleaner. You have to know where to look and when to look to get enough to eat, or to sell. The gleaners are interesting individuals, and they're happy to talk about what they do. Varda has taken what they told her, and fashioned it into a fascinating movie.

The irony of this is clear when you look at the French title of the movie. The film is about gleaners, but it's also about one gleaner--Agnès Varda. Varda uses the bits and pieces offered to her by the gleaners, and fashions them into a movie. So, in that sense, she herself is the ultimate gleaner.

We saw the film on the large screen at Rochester's Dryden Theatre, as part of the excellent Rochester Labor Film Festival. However, it should also work on DVD.

क्या आपको पता है

- ट्रिवियाThe film was included for the first time in 2022 on the critics' poll of Sight and Sound's list of the greatest films of all time, at number 67.

- भाव

Agnès Varda: He looked at an empty clock but put it back down. I picked it up and took it home. A clock without hands works fine for me. You don't see time passing.

- साउंडट्रैकApfelsextett

Composed by Pierre Barbaud

टॉप पसंद

रेटिंग देने के लिए साइन-इन करें और वैयक्तिकृत सुझावों के लिए वॉचलिस्ट करें

- How long is The Gleaners & I?Alexa द्वारा संचालित

विवरण

बॉक्स ऑफ़िस

- US और कनाडा में सकल

- $1,55,320

- US और कनाडा में पहले सप्ताह में कुल कमाई

- $12,655

- 11 मार्च 2001

- दुनिया भर में सकल

- $1,59,165

- चलने की अवधि

- 1 घं 22 मि(82 min)

- रंग

- पक्ष अनुपात

- 1.33 : 1

इस पेज में योगदान दें

किसी बदलाव का सुझाव दें या अनुपलब्ध कॉन्टेंट जोड़ें