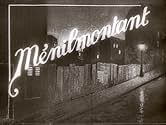

Ménilmontant

- 1926

- 38 मि

IMDb रेटिंग

7.8/10

2.9 हज़ार

आपकी रेटिंग

अपनी भाषा में प्लॉट जोड़ेंA couple is brutally murdered in the working-class district of Paris. Later on, the narrative follows the lives of their two daughters, both in love with a Parisian thug and leading them to ... सभी पढ़ेंA couple is brutally murdered in the working-class district of Paris. Later on, the narrative follows the lives of their two daughters, both in love with a Parisian thug and leading them to separate ways.A couple is brutally murdered in the working-class district of Paris. Later on, the narrative follows the lives of their two daughters, both in love with a Parisian thug and leading them to separate ways.

फ़ीचर्ड समीक्षाएं

After the violent and brutal death of their parents, two sisters leave to the big city to live. There, one of the sisters falls in love with a young man, but he is unfaithful and she is left having to deal with her own lost dreams and a baby without a job or a friend.

This is an interesting experimental film. It shows a lot more violence and sex than typically shown at the time, and yet it is very contemplative and serene in parts. However, as a subject of lost dreams, mostly it's very tragic. The image of interest here is the recurring motif of water. Water seems to provide all of the "insanity," including the boy seemingly coming from a spilt water barrel and a long montage of the woman contemplating something drastic as she looks out over the river.

It's powerfully affecting. It's strongest when hectic, during death or violence (beginning and end) or the sudden change from the serene quiet of the country to the speed and confusion of the city. It is a tragedy in every way, as lives are shattered in one way or another until a rather biting climax.

--PolarisDiB

This is an interesting experimental film. It shows a lot more violence and sex than typically shown at the time, and yet it is very contemplative and serene in parts. However, as a subject of lost dreams, mostly it's very tragic. The image of interest here is the recurring motif of water. Water seems to provide all of the "insanity," including the boy seemingly coming from a spilt water barrel and a long montage of the woman contemplating something drastic as she looks out over the river.

It's powerfully affecting. It's strongest when hectic, during death or violence (beginning and end) or the sudden change from the serene quiet of the country to the speed and confusion of the city. It is a tragedy in every way, as lives are shattered in one way or another until a rather biting climax.

--PolarisDiB

Watched Dimitri Kirsanoff's Ménilmontant last night. It's right out of the top drawer. Filmed in 1926 when the rubric for making a film was not yet set, the rules not there to be broken. You can sense the sheer vitality that the filmmaker is enabled with because of this. It feels like a Zola novel, a great portrait of urban life, and also a valuable document of the way Paris looked at the time. Kirsanoff is not weighed down by cinematic antecedents, there are no Hitchockian homages, no cinematic in-jokes, no nods to popular culture, no product placement. This makes the film alive with atmosphere, almost overflowing with it. Somehow Mr Kirsanoff places you in the film, makes you an insider to the innocence of childhood, the loneliness of the big city, the despair of poverty, the shock of betrayal.

His camera is like the Kino-Eye, and it looks at things the way real people look at them, making it the least phallic use of a camera that I have seen. The shots of the Seine, of the countryside, of Ménilmontant, and the roving, lingering, pace of the camera were quite literally breath-taking. There are no intertitles in this silent movie, and the plot is a little opaque, but really this is not taking the movie on its own terms, it is a masterpiece of camera-work and editing and provides the most atmosphere of any movie I have ever seen. It is ESSENTIAL to watch this movie at its 38 minute pace. I saw it on the double-disc Kino edition of Avant-garde: Experimental Cinema of the 1920s and 30s. This is the best value for money DVD on the market full stop.

Recently I watched Lang's The Testament of Dr Mabuse and became aware through his virtuosic use of sound, how taken for granted sound is in movies these days. Watching Ménilmontant makes you realise how taken for granted image is, most of modern cinema is simply about dubious storytelling to quote something I heard on TV, " it's a cultural wasteland filled with inappropriate metaphors and an unrealistic portrayal of life created by the liberal media elite". I recommend this movie to all lovers of cinema, it really is a movie that can make you once again enthuse about the moving image.

His camera is like the Kino-Eye, and it looks at things the way real people look at them, making it the least phallic use of a camera that I have seen. The shots of the Seine, of the countryside, of Ménilmontant, and the roving, lingering, pace of the camera were quite literally breath-taking. There are no intertitles in this silent movie, and the plot is a little opaque, but really this is not taking the movie on its own terms, it is a masterpiece of camera-work and editing and provides the most atmosphere of any movie I have ever seen. It is ESSENTIAL to watch this movie at its 38 minute pace. I saw it on the double-disc Kino edition of Avant-garde: Experimental Cinema of the 1920s and 30s. This is the best value for money DVD on the market full stop.

Recently I watched Lang's The Testament of Dr Mabuse and became aware through his virtuosic use of sound, how taken for granted sound is in movies these days. Watching Ménilmontant makes you realise how taken for granted image is, most of modern cinema is simply about dubious storytelling to quote something I heard on TV, " it's a cultural wasteland filled with inappropriate metaphors and an unrealistic portrayal of life created by the liberal media elite". I recommend this movie to all lovers of cinema, it really is a movie that can make you once again enthuse about the moving image.

Menilmontant (1926) was, in the modest context of the alternative cinema circuit, a smash hit. It's great success allowed filmmaker Dimitri Kirsanov to go on making films, and also helped Jean Tedesco to stay in business as an exhibitor.

Like Kirsanov's first film, Menilmontant (again starring Kirsanoff's first wife, the beautiful Nadia Sibirskaia) tells a story without the use of inter-titles. It is often said that the filmmakers cinema is poetic, but one must add that in his second film he explored the poetics of violence and degradation.

The story begins and ends with two unrelated, but similarly filmed and edited murders. In each case, the grisly event does not grow organically out of the plot, but seems to surge out of a world welling with violent impulses.

Menilmontant uses practically all of the typical stylistic devices of cinematic impressionism, but it is hard to consider it as in any way representative of the movement. It's overwhelming, virtually unrelieved violence and despair seem to infect its own storytelling agency, upsetting what in other filmmakers' works would be clearly delineated relations of parts to the whole.

The film contains several bursts of rapid editing, for example, but they are not rhythmic in any simple, narratively justified way (in the manner of Abel Gance, for example); their meter is complicated and unsettling, worthy of an Igor Stravinsky. The film offers several notable examples of subjective camera work, but typically these become slightly unhinged, with no absolute certainty as to which character's experience in being rendered.

Menilmontant is, quite deliberately, a film in which the formal center cannot hold, because it is about a world in which this is also true. Although certainly not a Surrealist work, it shares with Surrealism no only a fascination with violence and sexuality, but also a display of forces and transcend, and question the boundaries of, individual human consciousness.

Kirsanov concluded his Menilmontant with a shot of impoverished and exploited young women fashioning artificial flowers in the poorest district of Paris, he provided us the most comprehensive image, aesthetic and social, of this form of cinema. Through a panoply of stylistic experiments and through glorious close-ups of the incomparably fragile face of Sibirskaia, Kirsanov thought he had shaped a harsh milieu into an exquisite flower. But a flower for whom? Menilmontant would become a major film on the cine-club and specialized cinema circuit, but never played to the people of the working class quatier that gave it its title. This was not Kirsanov's public anyway, for he came from the Russian aristocracy. In 1919, having fled the Revolution, he was reduced to playing his beloved cello in movie houses just to be able to eat. He must have been tempted to imagine himself and his music as an unappreciated flower in the crude milieu of mass art.

Seen this way, Menilmontant becomes a personal triumph of art over industry, of the icon of Sibirskaia over the brutal world of plot and spectacle that constitutes ordinary cinema. That triumph is signaled in the miracle of the film's narration, the first French film without titles, a tale told completely through the eloquence of its images. The dark alleys of the nineteenth arrondissment, the streetlights listening on the Seine, and the pathetic decor of shabby apartments are all redeemed by art. No silent film more clearly bewails the fate of art in our century, more obviously appeals to connoisseurs of the emotions roused by artificial flowers.

Like Kirsanov's first film, Menilmontant (again starring Kirsanoff's first wife, the beautiful Nadia Sibirskaia) tells a story without the use of inter-titles. It is often said that the filmmakers cinema is poetic, but one must add that in his second film he explored the poetics of violence and degradation.

The story begins and ends with two unrelated, but similarly filmed and edited murders. In each case, the grisly event does not grow organically out of the plot, but seems to surge out of a world welling with violent impulses.

Menilmontant uses practically all of the typical stylistic devices of cinematic impressionism, but it is hard to consider it as in any way representative of the movement. It's overwhelming, virtually unrelieved violence and despair seem to infect its own storytelling agency, upsetting what in other filmmakers' works would be clearly delineated relations of parts to the whole.

The film contains several bursts of rapid editing, for example, but they are not rhythmic in any simple, narratively justified way (in the manner of Abel Gance, for example); their meter is complicated and unsettling, worthy of an Igor Stravinsky. The film offers several notable examples of subjective camera work, but typically these become slightly unhinged, with no absolute certainty as to which character's experience in being rendered.

Menilmontant is, quite deliberately, a film in which the formal center cannot hold, because it is about a world in which this is also true. Although certainly not a Surrealist work, it shares with Surrealism no only a fascination with violence and sexuality, but also a display of forces and transcend, and question the boundaries of, individual human consciousness.

Kirsanov concluded his Menilmontant with a shot of impoverished and exploited young women fashioning artificial flowers in the poorest district of Paris, he provided us the most comprehensive image, aesthetic and social, of this form of cinema. Through a panoply of stylistic experiments and through glorious close-ups of the incomparably fragile face of Sibirskaia, Kirsanov thought he had shaped a harsh milieu into an exquisite flower. But a flower for whom? Menilmontant would become a major film on the cine-club and specialized cinema circuit, but never played to the people of the working class quatier that gave it its title. This was not Kirsanov's public anyway, for he came from the Russian aristocracy. In 1919, having fled the Revolution, he was reduced to playing his beloved cello in movie houses just to be able to eat. He must have been tempted to imagine himself and his music as an unappreciated flower in the crude milieu of mass art.

Seen this way, Menilmontant becomes a personal triumph of art over industry, of the icon of Sibirskaia over the brutal world of plot and spectacle that constitutes ordinary cinema. That triumph is signaled in the miracle of the film's narration, the first French film without titles, a tale told completely through the eloquence of its images. The dark alleys of the nineteenth arrondissment, the streetlights listening on the Seine, and the pathetic decor of shabby apartments are all redeemed by art. No silent film more clearly bewails the fate of art in our century, more obviously appeals to connoisseurs of the emotions roused by artificial flowers.

The Ménilmontant depicted here by Dimitri Kirsanofff is a far cry from the picturesque village of Charles Trenet's famous chanson. The grim and narrow cobbled streets provide a backdrop for a film of which the subject matter is that of conventional melodrama but which has been raised by Dimitri Kirsanoff to the level of cinematic art.

The stylistic effects he employs are those of Impressionism, notably rapid montage, superimposition and flashbacks but never at the expense of the narrative and nigh-on a century later the film's emotive power has not diminished and remains a devastating piece of social realism which concerns two orphaned sisters who are eventually reconciled, having been betrayed by the same man.

Suffice to say the lynchpin is the director's wife and muse Nadia Sibirskaia whose face is adored by the camera and whose performance as the younger sister is stunning in its simplicity.

The mood of the film is heightened by the newly composed score of the talented Paul Mercer.

This is the second and indeed oldest surviving film of Russian émigré Kirsanoff and although to my knowledge he never again reached such heights this piece of ciné poetry guarantees his immortality.

The stylistic effects he employs are those of Impressionism, notably rapid montage, superimposition and flashbacks but never at the expense of the narrative and nigh-on a century later the film's emotive power has not diminished and remains a devastating piece of social realism which concerns two orphaned sisters who are eventually reconciled, having been betrayed by the same man.

Suffice to say the lynchpin is the director's wife and muse Nadia Sibirskaia whose face is adored by the camera and whose performance as the younger sister is stunning in its simplicity.

The mood of the film is heightened by the newly composed score of the talented Paul Mercer.

This is the second and indeed oldest surviving film of Russian émigré Kirsanoff and although to my knowledge he never again reached such heights this piece of ciné poetry guarantees his immortality.

Dimitri Kirsanoff, born in Estonia but operating mostly in Paris, was heavily influenced by the theories of Soviet Montage. In his most famous short film, 'Ménilmontant (1926)' still frightfully obscure in most circles he adheres to this style strictly, almost obsessively. His preference towards a brisk editing pace carries a unique vitality that is also seen in the work of Soviet masters Eisenstein and Vertov, who pioneered and perfected the technique of montage in the mid-to-late 1920s. But, nevertheless, I don't think it works quite as well here. 'The Battleship Potemkin (1925)' and 'The Man with the Movie Camera (1929) perhaps the two most recognised works of Soviet montage utilise their chosen editing style to full effect precisely because they place greater emphasis on the collective over the individual, in accordance with traditional Communist ideology. There is deliberately no emotional connection attempted nor made between the viewer and any individual movie character, for that would be contrary to the filmmaker's intentions (interestingly, however, the montage fell out of preference from the 1930s in favour of Soviet realism).

'Ménilmontant' falters because it strives to create an emotional connection with the characters (particularly the younger sister, played by Nadia Sibirskaïa), but Kirsanoff's chosen editing style continually keeps the audience at an arm's length. The closest he comes to true pathos is with the park-bench sequence, when an old man offers some bread and meat to the famished woman, delicately avoiding eye contact to preserve her dignity. Even in this scene, the montage style intrudes. A director like Chaplin (and I'm a romantic at heart, so he's naturally one of favourite filmmakers) would have placed the camera at a distance, framing the profiles of both the woman and the old man within the same shot, thus capturing the subtle emotions and inflections of both parties simultaneously. Kirsanoff somewhat confuses the scene, cutting sequentially between the woman, the man and the food in a manner that reduces a simple, poignant act of kindness into a technical exercise in film editing. It works adequately, of course, a precise demonstration of the Kuleshov Effect, but there's relatively little heart in it.

But we'll cease with my complaints hereafter. I know my own film tastes well enough to recognise that what I disliked about the film its emotional distance, for example represents precisely what others love about it. There's no doubting that the photography (when it's kept on screen long enough) is breathtakingly spectacular, making accomplished use of lighting, shadows and in-camera optical effects such as dissolves, irises and superimpositions. There are touches of the surreal. Kirsanoff cuts non-discriminately forwards in time, backwards and into his characters' dreams, fragmenting time and reality into a series of shattered images, their individual meanings obscure until considered sequentially as in the pieces of a puzzle. Most impressive, I thought, was how several shots captured the linear perspective of roads and alleys, watching his characters gradually depart into the distance as though merely following the predetermined pathways of their future. The film ends exactly as it begins with a bloody and unexplained murder suggesting the inevitable cycle of human suffering, its causes unknown and forever incomprehensible.

'Ménilmontant' falters because it strives to create an emotional connection with the characters (particularly the younger sister, played by Nadia Sibirskaïa), but Kirsanoff's chosen editing style continually keeps the audience at an arm's length. The closest he comes to true pathos is with the park-bench sequence, when an old man offers some bread and meat to the famished woman, delicately avoiding eye contact to preserve her dignity. Even in this scene, the montage style intrudes. A director like Chaplin (and I'm a romantic at heart, so he's naturally one of favourite filmmakers) would have placed the camera at a distance, framing the profiles of both the woman and the old man within the same shot, thus capturing the subtle emotions and inflections of both parties simultaneously. Kirsanoff somewhat confuses the scene, cutting sequentially between the woman, the man and the food in a manner that reduces a simple, poignant act of kindness into a technical exercise in film editing. It works adequately, of course, a precise demonstration of the Kuleshov Effect, but there's relatively little heart in it.

But we'll cease with my complaints hereafter. I know my own film tastes well enough to recognise that what I disliked about the film its emotional distance, for example represents precisely what others love about it. There's no doubting that the photography (when it's kept on screen long enough) is breathtakingly spectacular, making accomplished use of lighting, shadows and in-camera optical effects such as dissolves, irises and superimpositions. There are touches of the surreal. Kirsanoff cuts non-discriminately forwards in time, backwards and into his characters' dreams, fragmenting time and reality into a series of shattered images, their individual meanings obscure until considered sequentially as in the pieces of a puzzle. Most impressive, I thought, was how several shots captured the linear perspective of roads and alleys, watching his characters gradually depart into the distance as though merely following the predetermined pathways of their future. The film ends exactly as it begins with a bloody and unexplained murder suggesting the inevitable cycle of human suffering, its causes unknown and forever incomprehensible.

क्या आपको पता है

- ट्रिवियाPauline Kael said this was her favorite film of all time.

- इसके अलावा अन्य वर्जनThis film was published in Italy in an DVD anthology entitled "Avanguardia: Cinema sperimentale degli anni '20 e '30", distributed by DNA Srl. The film has been re-edited with the contribution of the film history scholar Riccardo Cusin . This version is also available in streaming on some platforms.

- कनेक्शनFeatured in The language of the silent cinema 1895-1929 - Part II: 1926-1929 (1973)

टॉप पसंद

रेटिंग देने के लिए साइन-इन करें और वैयक्तिकृत सुझावों के लिए वॉचलिस्ट करें

विवरण

- चलने की अवधि38 मिनट

- रंग

- ध्वनि मिश्रण

- पक्ष अनुपात

- 1.33 : 1

इस पेज में योगदान दें

किसी बदलाव का सुझाव दें या अनुपलब्ध कॉन्टेंट जोड़ें