IMDb रेटिंग

7.9/10

27 हज़ार

आपकी रेटिंग

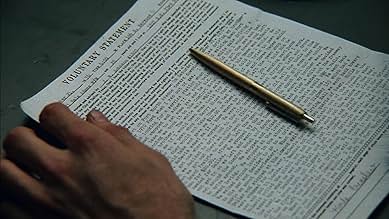

अपनी भाषा में प्लॉट जोड़ेंA film that successfully argued that a man was wrongly convicted for murder by a corrupt justice system in Dallas County, Texas.A film that successfully argued that a man was wrongly convicted for murder by a corrupt justice system in Dallas County, Texas.A film that successfully argued that a man was wrongly convicted for murder by a corrupt justice system in Dallas County, Texas.

- पुरस्कार

- 12 जीत और कुल 5 नामांकन

फ़ीचर्ड समीक्षाएं

"Thin Blue Line" is an early and extended version of "Forensic Files." The biggest difference is that "Forensic Files" focuses on the evidence used to catch a criminal whereas "Thin Blue Line" focused on evidence to exonerate a man falsely accused. Anyone not familiar with "Forensic Files," there's a narrator who recaps important points of the case along with interviews with important people to the case and some reenactment. "Thin Blue Line" had everything but the narrator.

If the justice system has fingered you as the culprit it is usually very hard to prove your innocence. Randall Adams found that out first hand. He was accused of killing a cop in Dallas in cold blood. There was very little evidence to tie him to the crime, but law enforcement saw to it that they got enough to convince a jury of his guilt.

The documentary isn't riveting by any means, and it's really a wonder why this case of who-knows-how-many was chosen for a documentary when there were probably far more egregious cases of injustice out there. Still, the documentary is good, especially for anyone concerned with the halls of justice.

If the justice system has fingered you as the culprit it is usually very hard to prove your innocence. Randall Adams found that out first hand. He was accused of killing a cop in Dallas in cold blood. There was very little evidence to tie him to the crime, but law enforcement saw to it that they got enough to convince a jury of his guilt.

The documentary isn't riveting by any means, and it's really a wonder why this case of who-knows-how-many was chosen for a documentary when there were probably far more egregious cases of injustice out there. Still, the documentary is good, especially for anyone concerned with the halls of justice.

I first saw this film not long after its initial release some 20 years ago and images and scenes from it have stayed with me ever since, so that it was with considerable anticipation that I re-watched it again recently. Down the years I can still recall Randall Adams drawling in his unforgettable voice "The kid scares me", the ever-revolving red light on the cop-car and most of all Philip Glass' wonderful, hypnotic music. The depiction of the fateful night of the cold-blooded murder of the policeman is shown from, almost literally, every possible angle, conveyed in a highly stylised way with almost every speculated remembrance of the doubtful list of every dubious (and are they ever dubious!) witness played out on the screen, the effect, in so doing, to completely explode their fantasist recollections, as was no doubt the director's aim. The reconstructions are set alongside filmed interviews of most of the main protagonists (with the main exception of the second cop in the car who witnessed the killing). As you watch these, the centrepiece clearly becomes the contrasting testimony of the almost-certain murderer David Harris with the wronged Randall Adams, the first coming across from the start as duplicitous and uncaring, the latter as bemused but reasoning. I was particularly taken with the erudition of Adams, who suppresses his inner rage with admirable restraint as he points the viewer time and again back to the evidence. As an indictment of the American criminal justice system, it hits home hard; it appears that investigation standards head for the hills especially when the law has a cop-killer to nail. Thankfully the miscarriage of justice was eventually resolved although it makes you grateful for the coincidence which led director Morris to change the subject course of his original project to instead highlight Adams' case culminating in his release soon after the film was first shown. The film however is more than a crusading documentary and there is much for students and admirers of the film-makers art to enjoy. Unforgettable, really, almost haunting, and proof if needed that truth really is stranger than fiction.

This is an extraordinary documentary in which film maker Errol Morris shows how an innocent man was convicted of murdering a policeman while the real murderer was let off scot free by the incompetent criminal justice system of Dallas, Texas. The amazing thing is that Morris demonstrates this gross miscarriage of justice in an utterly convincing manner simply by interviewing the participants. True, he reenacts the crime scene and flashes headlines from the newspaper stories to guide us, but it is simply the spoken words of the real murderer, especially in the cold-blooded, explosive audio tape that ends the film, that demonstrate not only his guilt but his psychopathic personality. And it is the spoken words of the defense attorneys, the rather substantial Edith James and the withdrawing Dennis White, and the wrongfully convicted Randall Adams that demonstrate the corrupt and incompetent methods used by the Dallas Country justice system to bring about this false conviction. Particularly chilling were the words of Judge Don Metcalfe, waxing teary-eyed, as he recalls listening to the prosecutor's summation about how society is made safe by that "thin blue line" of cops who give their lives to protect us from criminals. The chilling part is that while he is indulging his emotions he is allowing the cop killer to go free and helping to convict an innocent man. Almost as chilling in its revelation of just how perverted and corrupt the system has become, was the report of how a paid psychologist, as a means of justifying the death penalty, "interviewed" innocent Randall Adams for fifteen minutes and found him to be a danger to society, a blood-thirsty killer who would kill again.

This film will get your dander up. How the cops were so blind as to not see that 16-year-old David Harris was a dangerous, remorseless psychopath from the very beginning is beyond belief. He even took a delight in bragging about his crime. As Morris suggests, it was their desire to revenge the cop killing with the death penalty that blinded them to the obvious. They would rather fry an innocent man than convict the real murderer, who because of his age was not subject to the death penalty under Texas law. When an innocent man is wrongly convicted of a murder three things happen that are disastrous: One, an innocent man is in jail or even executed. Two, the real guilty party is free to kill again. And, three, the justice system is perverted. This last consequence is perhaps the worst. When people see their police, their courts, their judges condemning the innocent and letting the guilty walk free, they lose faith in the system and they begin to identify with those outside the system. They no longer trust the cops or the courts. The people become estranged from the system and the system becomes estranged from the people. This is the beginning of the breakdown of society. The Dallas cops and prosecutors and the stupid judge (David Metcalfe), who should have seen through the travesty, are to be blamed for the fact that David Harris, after he testified for the prosecution and was set free, did indeed kill again, as well as commit a number of other crimes of violence.

The beautiful thing about this film is, over and above the brilliance of its artistic construction, is that its message was so clear and so powerful that it led to the freeing of the innocent Randall Adams. Although the psychopathic David Harris, to my knowledge, was never tried for the crime he committed, he is in prison for other crimes and, it is hoped, will be there for the rest of his life. Errol Morris and the other people who made this fine film can pride in these facts and in knowing that they did a job that the Dallas criminal justice system was unable to do.

(Note: Over 500 of my movie reviews are now available in my book "Cut to the Chaise Lounge or I Can't Believe I Swallowed the Remote!" Get it at Amazon!)

This film will get your dander up. How the cops were so blind as to not see that 16-year-old David Harris was a dangerous, remorseless psychopath from the very beginning is beyond belief. He even took a delight in bragging about his crime. As Morris suggests, it was their desire to revenge the cop killing with the death penalty that blinded them to the obvious. They would rather fry an innocent man than convict the real murderer, who because of his age was not subject to the death penalty under Texas law. When an innocent man is wrongly convicted of a murder three things happen that are disastrous: One, an innocent man is in jail or even executed. Two, the real guilty party is free to kill again. And, three, the justice system is perverted. This last consequence is perhaps the worst. When people see their police, their courts, their judges condemning the innocent and letting the guilty walk free, they lose faith in the system and they begin to identify with those outside the system. They no longer trust the cops or the courts. The people become estranged from the system and the system becomes estranged from the people. This is the beginning of the breakdown of society. The Dallas cops and prosecutors and the stupid judge (David Metcalfe), who should have seen through the travesty, are to be blamed for the fact that David Harris, after he testified for the prosecution and was set free, did indeed kill again, as well as commit a number of other crimes of violence.

The beautiful thing about this film is, over and above the brilliance of its artistic construction, is that its message was so clear and so powerful that it led to the freeing of the innocent Randall Adams. Although the psychopathic David Harris, to my knowledge, was never tried for the crime he committed, he is in prison for other crimes and, it is hoped, will be there for the rest of his life. Errol Morris and the other people who made this fine film can pride in these facts and in knowing that they did a job that the Dallas criminal justice system was unable to do.

(Note: Over 500 of my movie reviews are now available in my book "Cut to the Chaise Lounge or I Can't Believe I Swallowed the Remote!" Get it at Amazon!)

The last few years have been a golden age for documentaries. For better or worse, Michael Moore and his undeniable ability for manipulating the cinematic medium have brought this endangered genre into theaters and living rooms across the country. Most of today's casual moviegoers are relatively new to the non-fiction feature. In the case of director Errol Morris' The Thin Blue Line (1988), one film not only managed to free an innocent man from a lifetime in prison, but it also elicited a confession from the guilty party. After collecting dust on video shelves for over fifteen years, this groundbreaking documentary has finally arrived on DVD.

Unless you're a devout cinephile or a video store clerk, you have probably never heard much about Errol Morris. As a member of the former category, I've been a fan of his since first renting The Thin Blue Line more than a decade ago. As I popped in that dusty VHS cassette and sat back, I relished what many critics and documentary purists had been hotly debating: Morris was taking the genre to exciting new places, whether people liked it or not.

As with all successful movies, a good doc needs a good story. In 1976, Dallas County police officer Robert Wood and his partner were patrolling their district late one night. The two pulled a blue car over to the side of the road, most likely to warn the driver of a busted taillight. Moments later Officer Wood was lying on the ground, fatally wounded by a series of gunshots. His partner quickly ran to his aid, but was unable to accurately retain and recall certain information about the killer's vehicle. Was it a Vega or a Comet? Did the driver have bushy hair or a fur-lined collar? These and many other questions emerged during the rushed investigation to bring the mysterious cop-killer to justice.

The film itself opens more than ten years after the murder took place. Randall Adams, an oddly charismatic good ol' boy sits before the camera, revealing what happened that unfortunate evening in late 1976. He admits to having shared a ride with a young kid named David Harris. The two apparently attended a drive-in double feature, where they both drank beer and smoked marijuana. Shortly thereafter, Adams claims to have been dropped off at his motel for the evening. Meanwhile, Morris shows us the aforementioned David Harris, now in his mid-20s, talking cryptically about that night's events. This real-life Rashomon confronts viewers with several versions of "the truth." It's unclear whether Morris instinctively knew the truth was still out there when he decided to pursue this project, but his previous experience as a private investigator seems to have paid off as we witness his off- camera interrogation of these two men.

Adams, responsible or not, was determined guilty by the courts and sentenced to death. Despite having a police record as long as his shadow, David Harris became the primary witness against Adams in the case. His testimony alone might not have hung Adams, but at the last minute a trio of eyewitnesses to the crime emerged to corroborate his story. In the world of Errol Morris, people are a truly strange lot, and his greatest technique is to simply let his subjects talk and talk until their inherent weirdness becomes painfully evident. Such is the case with the three last-minute witnesses in the Adams case. The more we hear them speak, the greater that uneasy feeling in our stomach and chest becomes. We are bearing witness to a catastrophic miscarriage of justice.

Morris employs a bottomless bag of tricks in this landmark film. While much of the film does rely on the presence of talking heads, he adds other elements to the mix, such as old movie footage, a haunting score by renowned composer Philip Glass, and the granddaddy of documentary no-no's: dramatic re-enactments. The latter tends to be the most challenged aspect of The Thin Blue Line, but Morris uses it fairly and wisely. He tells this twisted tale in ways few people could. A shot of a swaying timepiece or a concession stand popcorn machine suddenly amount to much more than what we're simply seeing on the screen. All of these pieces are being put together, little by little, in the hopes that by the end we will see the bigger picture.

When this movie was released in 1988, it was marketed as a non-fiction film, because the word "documentary" was thought to scare off ticket-buyers. The studio's attempts to pass it off as a murder mystery failed, but the movie made a minor splash once it hit video. It picked up plenty of awards from festivals and critics groups, but the Oscars didn't even bother nominating it. In fact, the Academy didn't so much as nod in Morris' direction until early 2004, when they nominated The Fog of War, his powerful, relevant look at former U.S. Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara. That film and Morris' two previous masterpieces, Mr. Death and Fast, Cheap & Out of Control have been available on DVD for some time. His first three films, Gates of Heaven, Vernon, Florida, and The Thin Blue Line, were recently made available either individually or in a 3-disc box set. All six of these films are unique, intriguing portals into Mr. Morris' strange universe, which is not so distant from our own. If it's dramatic situations, reality TV, or simply a great movie that you want, look no further than The Thin Blue Line. As one of the greatest documentaries of our time, it is all these things and so much more.

Rating: A

Unless you're a devout cinephile or a video store clerk, you have probably never heard much about Errol Morris. As a member of the former category, I've been a fan of his since first renting The Thin Blue Line more than a decade ago. As I popped in that dusty VHS cassette and sat back, I relished what many critics and documentary purists had been hotly debating: Morris was taking the genre to exciting new places, whether people liked it or not.

As with all successful movies, a good doc needs a good story. In 1976, Dallas County police officer Robert Wood and his partner were patrolling their district late one night. The two pulled a blue car over to the side of the road, most likely to warn the driver of a busted taillight. Moments later Officer Wood was lying on the ground, fatally wounded by a series of gunshots. His partner quickly ran to his aid, but was unable to accurately retain and recall certain information about the killer's vehicle. Was it a Vega or a Comet? Did the driver have bushy hair or a fur-lined collar? These and many other questions emerged during the rushed investigation to bring the mysterious cop-killer to justice.

The film itself opens more than ten years after the murder took place. Randall Adams, an oddly charismatic good ol' boy sits before the camera, revealing what happened that unfortunate evening in late 1976. He admits to having shared a ride with a young kid named David Harris. The two apparently attended a drive-in double feature, where they both drank beer and smoked marijuana. Shortly thereafter, Adams claims to have been dropped off at his motel for the evening. Meanwhile, Morris shows us the aforementioned David Harris, now in his mid-20s, talking cryptically about that night's events. This real-life Rashomon confronts viewers with several versions of "the truth." It's unclear whether Morris instinctively knew the truth was still out there when he decided to pursue this project, but his previous experience as a private investigator seems to have paid off as we witness his off- camera interrogation of these two men.

Adams, responsible or not, was determined guilty by the courts and sentenced to death. Despite having a police record as long as his shadow, David Harris became the primary witness against Adams in the case. His testimony alone might not have hung Adams, but at the last minute a trio of eyewitnesses to the crime emerged to corroborate his story. In the world of Errol Morris, people are a truly strange lot, and his greatest technique is to simply let his subjects talk and talk until their inherent weirdness becomes painfully evident. Such is the case with the three last-minute witnesses in the Adams case. The more we hear them speak, the greater that uneasy feeling in our stomach and chest becomes. We are bearing witness to a catastrophic miscarriage of justice.

Morris employs a bottomless bag of tricks in this landmark film. While much of the film does rely on the presence of talking heads, he adds other elements to the mix, such as old movie footage, a haunting score by renowned composer Philip Glass, and the granddaddy of documentary no-no's: dramatic re-enactments. The latter tends to be the most challenged aspect of The Thin Blue Line, but Morris uses it fairly and wisely. He tells this twisted tale in ways few people could. A shot of a swaying timepiece or a concession stand popcorn machine suddenly amount to much more than what we're simply seeing on the screen. All of these pieces are being put together, little by little, in the hopes that by the end we will see the bigger picture.

When this movie was released in 1988, it was marketed as a non-fiction film, because the word "documentary" was thought to scare off ticket-buyers. The studio's attempts to pass it off as a murder mystery failed, but the movie made a minor splash once it hit video. It picked up plenty of awards from festivals and critics groups, but the Oscars didn't even bother nominating it. In fact, the Academy didn't so much as nod in Morris' direction until early 2004, when they nominated The Fog of War, his powerful, relevant look at former U.S. Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara. That film and Morris' two previous masterpieces, Mr. Death and Fast, Cheap & Out of Control have been available on DVD for some time. His first three films, Gates of Heaven, Vernon, Florida, and The Thin Blue Line, were recently made available either individually or in a 3-disc box set. All six of these films are unique, intriguing portals into Mr. Morris' strange universe, which is not so distant from our own. If it's dramatic situations, reality TV, or simply a great movie that you want, look no further than The Thin Blue Line. As one of the greatest documentaries of our time, it is all these things and so much more.

Rating: A

A film that successfully argued that a man (Randall Dale Adams) was wrongly convicted for murder by a corrupt justice system in Dallas County, Texas.

Morris was originally going to film a documentary about prosecution psychiatrist, Dr. James Grigson, known as Doctor Death, who testified in more than 100 trials that resulted in death sentences. In almost every instance, Dr. Grigson would, after examining a defendant, testify that he had found the individual in question to be an incurable sociopath, who it was "one hundred per cent certain" would kill again.

This lead Morris to find an example, Adams, where this "incurable sociopath" status was in doubt. But we also still have that critique of Grigson -- we see what he said about Adams, a man with no history of criminal acts or violence, after only fifteen minutes with him.

This change in focus lead to a better film, most likely (though Erroll Morris has an incredible track record for good documentaries). We now get to see a wider picture of eyewitness testimony, the prejudice of the area (which includes a thriving KKK) and more.

Adams' case was reviewed and he was released from prison approximately a year after the film's release. Now that is the sign of a powerful film, and what makes documentaries so great.

Morris was originally going to film a documentary about prosecution psychiatrist, Dr. James Grigson, known as Doctor Death, who testified in more than 100 trials that resulted in death sentences. In almost every instance, Dr. Grigson would, after examining a defendant, testify that he had found the individual in question to be an incurable sociopath, who it was "one hundred per cent certain" would kill again.

This lead Morris to find an example, Adams, where this "incurable sociopath" status was in doubt. But we also still have that critique of Grigson -- we see what he said about Adams, a man with no history of criminal acts or violence, after only fifteen minutes with him.

This change in focus lead to a better film, most likely (though Erroll Morris has an incredible track record for good documentaries). We now get to see a wider picture of eyewitness testimony, the prejudice of the area (which includes a thriving KKK) and more.

Adams' case was reviewed and he was released from prison approximately a year after the film's release. Now that is the sign of a powerful film, and what makes documentaries so great.

क्या आपको पता है

- ट्रिवियाErrol Morris spent 2-1/2 years tracking down the various players in the Randall Adams case and convincing them to appear in the film.

- गूफ़David Harris talks about his older brother drowning at the age of four in 1963. He says it occurred "right after President Kennedy was assassinated I believe. Sometime right after that. During the summer". However Kennedy was killed in the third week of November, well after summer.

- भाव

Melvyn Carson Bruder: Prosecutors in Dallas have said for years - any prosecutor can convict a guilty man. It takes a great prosecutor to convict an innocent man.

- क्रेज़ी क्रेडिटDrawings from the Bender Visual Motor Gestalt Test © 1946, American Orthopsychiatric Association Inc. and Lauretta Bender, M.D.

टॉप पसंद

रेटिंग देने के लिए साइन-इन करें और वैयक्तिकृत सुझावों के लिए वॉचलिस्ट करें

- How long is The Thin Blue Line?Alexa द्वारा संचालित

विवरण

बॉक्स ऑफ़िस

- US और कनाडा में सकल

- $12,09,846

- US और कनाडा में पहले सप्ताह में कुल कमाई

- $17,814

- 28 अग॰ 1988

- दुनिया भर में सकल

- $12,09,846

- चलने की अवधि1 घंटा 41 मिनट

- रंग

- ध्वनि मिश्रण

- पक्ष अनुपात

- 1.85 : 1

इस पेज में योगदान दें

किसी बदलाव का सुझाव दें या अनुपलब्ध कॉन्टेंट जोड़ें