एक कुंठित युद्ध संवाददाता, जिसे कि एक युद्ध कवर करने के लिए कहा गया था, वह उस युद्ध को खोजने में असमर्थ है, वह एक मृत हथियार डीलर के परिचित होने का स्वांग रचकर एक जोखिम भरा रास्ता चुनता है.एक कुंठित युद्ध संवाददाता, जिसे कि एक युद्ध कवर करने के लिए कहा गया था, वह उस युद्ध को खोजने में असमर्थ है, वह एक मृत हथियार डीलर के परिचित होने का स्वांग रचकर एक जोखिम भरा रास्ता चुनता है.एक कुंठित युद्ध संवाददाता, जिसे कि एक युद्ध कवर करने के लिए कहा गया था, वह उस युद्ध को खोजने में असमर्थ है, वह एक मृत हथियार डीलर के परिचित होने का स्वांग रचकर एक जोखिम भरा रास्ता चुनता है.

- पुरस्कार

- 5 जीत और कुल 2 नामांकन

- Robertson

- (as Chuck Mulvehill)

- Hotel Clerk

- (बिना क्रेडिट के)

- Murderer's accomplice

- (बिना क्रेडिट के)

- Cameraman

- (बिना क्रेडिट के)

फ़ीचर्ड समीक्षाएं

"The Passenger will remain a film of the mid '70s, as one of Antonioni's previous films, Blow-Up, remains a film for and symbolises the '60s. It also contains one of Jack Nicholson's definitive performances (along with Chinatown, The Last Detail and One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest) and has, perhaps, been a trifle overshadowed by these films all emerging within a short period of time of each other and the enormous publicity and word-of-mouth they have generated. But The Passenger has proved itself a strangely durable film and, like Chinatown, one that will remain around for a long time, both in the consciousness of its admirers and, one hopes, constant revivals.

Antonioni's third English-speaking film, The Passenger, like Blow-Up and Zabriskie Point, centres around the oblique, unresolved aspects of life. In Antonioni's films - as in life - there are no easy answers, things are not tidied up, explained, sorted out.

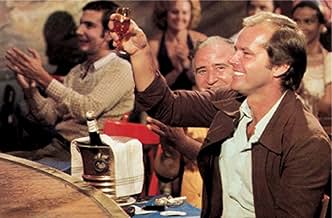

So it is with The Passenger. Jack Nicholson is Locke, an outwardly successful television journalist, but he also is being eaten away by his own disillusionment with the job and the value of his interviews, and that general malaise that affects Antonioni's people. When the film begins, we find him on location in Chad where his jeep breaks down and gets bogged in the sand. Locke breaks down and collapses on the sand as the camera pans away over the strange but beautiful desert panorama.

We next see Locke, in an advanced state of exhaustion, struggling back to his hotel and a cool shower, and discovering that the man in the next room, who looks rather like him, has died. We are very conscious of the stillness in the hotel - the blue walls, a fly buzzing, the noise of the fan, Locke staring intently at the dead man on the bed. We hear their dialogue of the previous evening and the aural flashback changes to a visual one by some very neat editing. Locke changes rooms, passport photos and luggage, and finds it quite easy to take on a new identity. How desperate his need is can be judged by his conversations back in Europe with the free, liberated girl (Maria Schneider) he meets up with. ("I used to be somebody else, but I traded him in"). She, incidentally, is freer than Locke could ever be.

It transpires Locke has taken over the identity of a gun-runner, Robertson. Perhaps it is best not to go into the plot in too much detail. Best all round just to pick out some of the marvellous moments along the way to the final breathtaking conceit. There's Locke, back in London, daringly visiting his old haunts - delighting in being someone else, but of course he isn't. Later on he is suspended in a cable car high about the ocean his arms outstretched like a bird in flight. Later still, the girl asks him what he is running from, and he tells her to turn around and we see what she sees - the road behind them.

By now, we the audience are caught up in this mesmerising film and its deliberations of he mysteries of identity. We are now totally involved in Locke's plight. He has given up one identity for another and becomes more and more helpless as the situation gets out of his control. Finally, in a remote Spanish hotel he can go no further, either as himself or as his new identity, as his wife and the gun-runners close in on him. One shouldn't spoil the last sequence for those still to see it, but it shows the only real freedom from identity and self is in death. The final scene shows us the aftermath: as the sun goes down, the hotel-keeper comes out for a walk, a woman sits in the doorway resting. For some people, who do not question their existence, the continuity of life goes on.

Antonioni, now in his sixties, is one of the great Italian directors who, like Fellini and Visconti, burst upon the international film scene in the late '50s. His trilogy of Italian films, L'Avventura, La Notte and L'Eclisse, and his first colour film The Red Desert (all with Monica Vitti) contributed to the renaissance of the European cinema. Then he switched to his English-speaking films, of which Blow-Up was the first. He is as much a master of landscape as John Ford was in his genre. He thinks nothing of painting whole streets or trees to get the effect he wants. Blow-Up is the only film from the whole, crazy period of Swinging London films that has not dated and which encapsulates what it was really all about. It remains one of the great films. Like Bergman, Bunuel or Fellini you either respond to his vision or reject it totally. His images linger on in the mind, his work never dates."

That is what part of what I wrote in 1976 and The Passenger indeed remains endlessly fascinating and particularly so now that it is available again. Even at the Antonioni retrospective in 2005 it was not available to include in the season, but we did have cast members Jenny Runacre and Steve Berkoff there to speak warmly of it's making and importance.

Let's hope a new generation will discover its timeless appeal, and amazingly Antonioni now in his 90s is still with us, if rather frail. A 2005 short of his was shown last year on the great statue of Moses in Rome and was also in its own way fascinatingly mysterious.

As with the director's most celebrated film, Blowup (1966), The Passenger also deals with the ideas of sight and perception, and with a character - in this case a writer/television reporter - who literally creates his own story as the film progresses. With these factors in places we have an absolutely fascinating piece of work; one filled with endless ideas of interpretation and reinterpretation as we look at the accumulation of character information and the vague scenes that seem to suggest the background of this character in relation to his decisions that come to inform the direction of the plot. With this, we again come back to that central notion of identity and how it governs our journey through life, with the earliest scenes showing Nicholson's character to be lost (both literally and figuratively) in a pensive, limbo-like existence and finding his way out of this torturous situation by attempting to step into the shoes of a completely different character (again, an idea expressed in both the literal and metaphorical sense of the term). These ideas are depicted through Antonioni's fantastic use of time and space, as he places Nicholson, first as an insignificant speck in the midst of the African desert, and then eventually against an ever changing backdrop of exciting and exotic European locales, to literally convey his lack of significance within the world that he inhabits.

Nevertheless, the real enjoyment of the film comes from the eventual realisation that this character makes on the nature of existence and his place within it, and how Antonioni suggests this through his typically rigid and starkly beautiful direction and the actual mechanisms of the plot. As ever with Antonioni's work, the narrative here is structured in a subjective and episodic manner, moving from one scene to the next while offering us snatches of information that we can collect and consider within the perspective of that penultimate scene that seems to put the rest of the film into a kind of context. The director also uses flashbacks and cutaways to scenes that we assume have some precedence over the journey that the character is taking, though again, it could just as easily be connected to the political climate that the film suggests through the documentary footage shot by Nicholson's character before his eventual self-imposed exile from himself. Here, the implication of the film's English title becomes clear, with the character of David Locke becoming a literal passenger in his own life; an empty vessel just drifting through existence with no real interaction, boxed in by the confines of a disintegrating marriage and tied to a job that is slowly sucking the very essence from his being.

Though the film is as minimal and subtle as many of Antonioni's earlier films, such as his grand cinematic gesture, the so-called "alienation trilogy", comprising of the films L'avventura (1960), La Notte (1961) and L'Eclisse (1962), the ultimate themes are incredibly affecting and heartbreaking in their finality; with Locke becoming the representation of the literal lost soul, a ghost in his own life who finds escape through imitation, only to end up reliving the same nightmare as if trapped within some endless loop. For me, it is easy to identify with the ideas here; with the central concept of remaking your own life as someone else entirely - or to live our lives from another perspective - coming back to the often mistaken belief that the grass is always greener on the other side. This notion is suggested throughout the film, from the first very meeting between Locke and the enigmatic Robertson, to that final scene between David and the mysterious girl, in which Locke relates the somewhat heartbreaking parable of the blind man who, after finally regaining his sight on the eve of his 40th birthday, is literally overwhelmed by what a terrible state the world is in.

Metaphors run rife through the film, from Antonioni's visual abstractions within the frame, to the subtle use of wordplay within the script. The ending then ties the whole thing together with a masterful display of technical virtuosity and one of the great, enigmatic questions of Antonioni's career. It is sad, mostly in the same way that the endings of La Notte and L'Eclisse were sad, suggesting a thread of resigned disappointment and the rejection of escape in favour of the easiest option. Ultimately though, the film is deeper, more affecting and more fascinating than any of this particular review might suggest; with Antonioni producing one of his very greatest films, aided by the excellent performances from Nicholson and Maria Schneider, and that continually evasive and hypnotic tone of wandering melancholy, as we move slowly towards that inevitable final, and one of Antonioni's boldest and most purely defined artistic statements.

From the very first sequence, this is a starkly shot film with a very unique visual signature to everything you see. A desolate, exotic locale for a movie: the North African desert. But this desert setting is perfectly in accord with the refreshing cinematic technique of Michelangelo Antonioni, who always stressed economy. Just as in his other works, there are no unnecessary ornaments or frills here. He introduces us to the strange, existential story in this film, and its odd, solitary, lead character-- in as clean, pure, and undiluted terms as possible. The principle here is that 'less is more'.

Some people really dislike this about Antonioni. He uses his camera in such a quiet way; and there is just this single, very terse figure/ground relationship which is the focus of his attention. But I think he knows that character stands out with more relief when its set against a minimalist background. Here, because characterization is channeled through Jack Nicholson, (far better even than in 'Blow-up' with David Hemmings) its more than enough. The brevity and scarcity in the film funnels you straight into Nicholson's awesome talent. We are along with him for the ride.

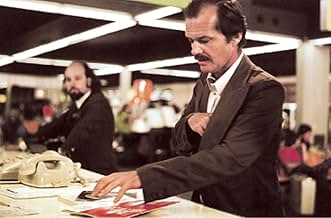

The plot starts out cryptically and simply, with very little explained about the man the camera spends so much time on. Jack Nicholson is a reporter named David Locke, and he is covering an African civil war. But beyond this, you must infer most everything else about him from just what you see-just by observing his behavior, and nothing else. There is scant dialogue of any kind. The depth of Nicholson's character is conveyed in miniscule components, parsed out after long intervals. His overall demeanor is weary, frustrated, sullen; the typical traveler who cant get good service. But he is also dispirited with his mission and in a way, despondent about his whole future and way of life.

Then suddenly, he sheds his persona and takes on someone elses'. He is staying in an isolated hotel and a man in the next room dies accidentally-and Nicholson decides to trade identities with the corpse; leaving the hotel with this new identity and letting everyone think it is he who has died. It's the personal reasons for this act, which Antonioni explores throughout the rest of the movie: the consequences and responsibilities incurred when you gamble upon coincidence and invest in random chance.

(II)

'Passenger' follows the progress of a man through a personal crisis; an identity transformation. The film is split with a Doppler-shift down the meridian of the identity theft Nicholson commits. His problems after this act consist of trying to make sure his ex-wife and employers continue to assume he is dead; and deciding how much of the false man's life and business to play at.

With the plot as its laid out this way, we might not ever really ever know the full reasons why Locke exchanged personality for that of another. But Antonioni adds some really clever flourishes: since Locke was a news journalist, the video interviews he conducted up to the point of his 'death' are available both to the people who begin to hunt him, and to us. We actually see more of Locke revealed in these flashbacks than we do in real-time. It adds just the right note. We get a better idea of the reasoning behind this bold act, why he casually gave up his whole history on a whim.

In his assignments up to this side trip to North Africa, we discern that Locke is dissatisfied with 'the rules' governing his profession. He is a talented observer, and wants to be a good reporter. But he finds all the news he gathers is in a way, pre-constrained by cultural filters. Its not raw enough, instead, its already been processed for him. In other words, he is never getting the real story; as long as he is a reporter, people frame their information for him as a reporter. As long as he is an Anglo, people treat him as an Anglo.

But after the identity-shedding transformation, he is free; and he has the time of his life. Returning to London, Locke amusedly begins playing the role of the dead man: keeping his engagements, carrying out business deals. Theres no accountability; he is pretending to be someone else. Only one thing: the dead man was an arms dealer and Nicholson is getting into deep trouble by masquerading this way. His philosophical pleasure may be cut short sooner than he expects. He doesnt see the trouble coming his way, but we do. Its a sort of combination of film noir and road-trip movie here; and it works.

(III)

Things begin to unravel. Shady customers start to dog his footsteps. Growing increasingly edgy, as he continues to follow the strange itinerary, Nicholson hooks up by coincidence with a young architecture student backpacking through Spain (well-played by petite, dusky, sensual Maria Schneider). They're an odd pair; but their joining forces makes one of a most intriguing screen romances of the period. She isn't given much to do in the screenplay, but makes a wonderful calming presence to the brittle Nicholson. Her character insists that Locke should, in all rationality, continue his journey--she is rigorous about principles. Locke acquiesces and he continues on, down along the coast of Spain towards Africa again, on his fool's errands, to meet his fate.

I wont expose any more of the plot. But I will say the final sequence of this movie is extremely startling and powerful. I had never even heard about it; in my opinion it should be talked about much, much more. Totally daring and innovative. Antonioni really shows what he can do here-you simply have to see it.

There are some flaws, yes: a few of Antonioni's flashbacks come off lame and awkward- too abrupt. They're really irksome. And there is a sloppy element in the final denoument, which I still cant understand: the drivers school vehicle. I yearn for the movie to be re-cut to remove these failings. But its still very satisfying as is.

(IV)

The bottom line here is that Nicholson has, in this film, a showcase for his talents like few other projects I have seen him in. This film was made in 1975, just a year after 'Chinatown' and the same year as his cameo in The Who's `Tommy' and his lead role in Milos Foreman's `One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest'. Jack is quite young, fit, and good-looking when he made this film. Its rewarding to remember him as he was then, before he both let himself go somewhat physically, and also began playing so many 'sick, horny focker' roles. This is one of the highlights of his entire life's work, imho. Easily as memorable as Jake Gittes or MacMurphy.

Jack is careful to do a good job in this movie--perhaps at this point in his career, he was still worried about major goof-ups. Its definitely prior to the point where he began to 'coast'. It looks like he took this film seriously--and probably enjoyed it immensely. Anyway, what other actor do you know today that could walk away with a difficult role like this one; an actor who would be as supremely interesting to us (as Nicholson is, in many scenes in this film) doing not much of anything for long moments at a time?

I doubt even DeNiro could have succeeded--he would have played it too 'tough-guy' and added too much gesture. Its Nicholson's laconic, dry twang, his sardonic gestures and those bored, squinty, seen-it-all eyes, that makes it work. There is a world-weariness about him in this performance that is quite special. The weight of past experiences exudes strongly from him; and its just what Antonioni needed. This quality defined him for this role like no other contemporary actor of his time.

Anyway, in this flick, you know he is doomed but you aren't really sure how Antonioni is going to do it. Antonioni creates massive tension with that very economical, severe camera style and almost no music. There are many scenes where the only sounds are the background noises from the environment itself; you can practically see Nicholson's sweat, hear his breath, and feel his pulse. Nicholson, surely very aware of this tight focus on him, maintains a rigid grip on his character throughout the film.

He isn't at all cocky--his special trait is his vulnerability. Nicholson always seems tough on the outside, but also as if he can still be hurt (as we see here, and in Chinatown as well). Its a vulnerability very like Bogart's in 'Casablanca'. In fact, if this film had been made in a previous generation, (as Gene Siskel once claimed) there would have been no there actor besides Bogart who could have even pulled it off. But no matter what: its great to see Nicholson on his own, competing with no other strong castmembers, just cruising along as a lone, insecure American among hostile and unfriendly foreigners.

His characterization is superbly restrained and un-showy; his gestures and expressions are as bland as possible; and there are no wildly quotable lines or speeches (any Nicholson fan should view this film for this reason alone). Anyway, by the end of the flick, you are positioned so closely alongside Nicholson--so wrapped up in his fate--that the brilliant, low-key finale can take you by surprise and it leaves a terrific poignancy.

In short, there are many reasons to like this film. I heartily recommend it. Its easily the best movie I have seen in some time. Its essential for appreciating both Nicholson and Antonioni. I encourage you to rent this movie on VHS as I am sure you will relish it as well.

"Professione: reporter", to me, belongs to the most interesting period of Antonioni's career (between the second half of the Sixties and the first of the Seventies). Because in these years the Italian director made his most accessible works: "Blow Up" (1966), "Zabryskie point" (1969) and "Professione: reporter" ("The Passenger", 1974). These films contain more action and more situations. They are neither more commercial nor more mainstream, but they talk about an adventure or a dream.

A journalist in North Africa switches the identity with a dead man who looks like him. He does this to escape from his life and for living a more interesting one. But he'll pay for his choice...

It's difficult to say, but this Antonioni movie (with his recurrent themes and -in a smaller way- times) has a lot of suspense, if I can say so. Once you begin to watch it, you can't give up. The funny thing is that nothing really big or special happens: sometimes it seems a road movie, sometimes it is a typical Antonioni analysis of the society. Jack Nicholson -how young he was at that time!- fills the film, his performance and his expressions are brilliant. It's also interesting the chemistry with Maria Schneider, the lady of "The last tango in Paris" -an actress who never got the fame and the recognition she deserved.

Cinematography is fantastic. But, above all, the big surprise of the film is the final shot: a 7-8 minutes take without cuts, absolute amazing. It's not describable, it's a must!

"I'd like to enquire about flights," Locke asks a hotel clerk. He seeks to escape his past. Later in the film, as he rides a cable cart, Locke spreads his arms and soars like a bird. He's flying, finally enjoying a brief moment of freedom.

The theme of identity, and Locke's name itself, immediately recalls the writings of English philosopher John Locke. Locke believed in the concept of the "tabula rasa" or blank slate. He believed that it was our experiences that defined us as people and that the only way to escape who we are is to effectively erase our history and cut ourselves off from experiences.

Throughout his writings, Locke emphasised the individual's freedom to author his or her own soul. Each individual was free to define his character, but his basic identity as a member of the human species could not be altered. So Locke had two ideas at war. Firstly the belief that the individual was free to author his own life, and secondly the belief that human nature is rigid and unchangeable. It is from this presumption of a free, self authored mind, combined with a sense of rigid human nature, that the Lockean doctrine of "natural" rights is derived.

In Antonioni's film, Nicholson articulates these ideas himself. He is trapped between wanting to be free and having to fulfil duties/roles/tasks embedded in the new persona he has acquired. While responding to a comment that all PLACES are the same, he even argues that it's actually the PEOPLE that are the same. That everyone conforms to specific cultural archetypes. The film's original title, "Profession: Reporter", highlights this point best.

Nicholson's character is desperate to escape this. Like his character in "Five Easy Pieces", he wants some unmappable freedom. He wants to be an individual. Beyond this, though, he wants to stay blank. In what is perhaps the film's most joyous moment, a female character asks Locke what he's running from. He tells her to turn her back to the front of the car. What occurs next is an instant of spontaneous elation and giddy happiness, as she watches the road rush away behind them.

But what people fail to notice during this scene, is that she is in fact watching the past. By facing her previous experiences (which Locke refuses to do) she is happy. Happiness comes from her memories and past encounters, while Locke is miserable simply because he refuses to acknowledge his past experiences.

Throughout the film Locke is asked whether he thinks "the landscape" is beautiful. Once he answers "no", another time he absent mindedly answers "yes", but Antonioni stresses that Locke is really not paying attention. Locke intentionally avoids absorbing beauty or new experiences in an effort to remain in a constant state of rebirth.

These themes are culminated in a brilliant "blind man" story towards the end of the film. Locke, a journalist who specialises in seeing and recording the truth, is painfully attuned to what he calls the "dirt" of the world. As such, he chooses to remain blind. A blank slate.

Antonioni is particularly good at endings and the final shot of "The Passenger" really elevates the whole film. Like the dead man, whose identity he took on, Locke dies alone and face down in a bed. His ex wife pops up and states that she never knew him, but nobody seems to care.

9/10- A great film, worth two viewings. It captures a profound sense of isolation and sadness. Antonioni's camera seems to capture the immense tiredness of the body. Rather than portray experiences, he shows what remains of past experiences. He shows what comes afterwards, when everything has been said. The middle portion of the film is slow and seems to be lacking some sort of superficial drama, but things build nicely and the final payoff well is worth the wait.

क्या आपको पता है

- ट्रिवियाWhen Michelangelo Antonioni received his honorary Oscar in 1995, the Academy asked Jack Nicholson to present it to him.

- गूफ़There are a couple of inaccuracies in the displayed details of Locke's Air Afrique air ticket that was evidently issued in Douala, Cameroon in August 1974. The name of Fort-Lamy (Chad's neighboring capital city) became N'djamena in early 1973, and Paris is written in Italian ("Parigi") which would not have occurred in French-speaking Douala.

- भाव

The Girl: Isn't it funny how things happen? All the shapes we make. Wouldn't it be terrible to be blind?

David Locke: I know a man who was blind. When he was nearly 40 years old, he had an operation and regained his sight.

The Girl: How was it like?

David Locke: At first he was elated... really high. Faces... colors... landscapes. But then everything began to change. The world was much poorer than he imagined. No one had ever told him how much dirt there was. How much ugliness. He noticed ugliness everywhere. When he was blind... he used to cross the street alone with a stick. After he regained his sight... he became afraid. He began to live in darkness. He never left his room. After three years he killed himself.

- क्रेज़ी क्रेडिटLeo, the MGM lion, which normally precedes the opening credits of MGM movies, has been supplanted by "BEGINNING OUR NEXT 50 YEARS". Leo then returns in the center with "GOLDEN ANNIVERSARY" on either side of it.

- इसके अलावा अन्य वर्जनSeven minutes were added to the 2005-2006 re-release version, including a brief shot of a nude Maria Schneider in bed with Jack Nicholson in the Spanish hotel.

- कनेक्शनFeatured in Z Channel: A Magnificent Obsession (2004)

टॉप पसंद

- How long is The Passenger?Alexa द्वारा संचालित

विवरण

- रिलीज़ की तारीख़

- कंट्री ऑफ़ ओरिजिन

- आधिकारिक साइट

- भाषाएं

- इस रूप में भी जाना जाता है

- Professione: Reporter

- फ़िल्माने की जगहें

- Fort Polignac, Algeria(desert scenes, setting: Chad)

- उत्पादन कंपनियां

- IMDbPro पर और कंपनी क्रेडिट देखें

बॉक्स ऑफ़िस

- US और कनाडा में सकल

- $6,20,155

- US और कनाडा में पहले सप्ताह में कुल कमाई

- $24,157

- 30 अक्टू॰ 2005

- दुनिया भर में सकल

- $7,69,503

इस पेज में योगदान दें