IMDb रेटिंग

7.4/10

10 हज़ार

आपकी रेटिंग

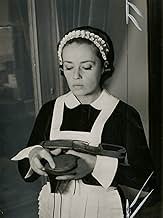

अपनी भाषा में प्लॉट जोड़ेंA sophisticated and self-assured woman from Paris joins a middle-class rural estate as a maid and causes quite a stir among the variously uptight, perverse and violent inhabitants.A sophisticated and self-assured woman from Paris joins a middle-class rural estate as a maid and causes quite a stir among the variously uptight, perverse and violent inhabitants.A sophisticated and self-assured woman from Paris joins a middle-class rural estate as a maid and causes quite a stir among the variously uptight, perverse and violent inhabitants.

- निर्देशक

- लेखक

- स्टार

- पुरस्कार

- 1 जीत और कुल 2 नामांकन

फ़ीचर्ड समीक्षाएं

I will say outright that not only is Luis Bunuel my favorite film director but I also consider him one of the ten of the all-time greatest. Rarely did a renowned film-maker make such a remarkable comeback after years of exile as Bunuel did with LOS OLVIDADOS (1950) and, even rarer still, did one director have such a sustained series of masterworks released towards the twilight of his career. Having said all this, however, I think that LE JOURNAL D'UNE FEMME DA CHAMBRE aka DIARY OF A CHAMBERMAID (1964) is the weakest of the final ten feature films Bunuel made during the most fruitful period of his career (between 1961 and 1977) if such a choice were to be made, that is.

Don't get me wrong; I do think that LE JOURNAL is an excellent film and would probably be considered a bona-fide masterpiece if it were made by a lesser director. There is much to enjoy in the film: Jeanne Moreau's superb central performance as the opportunistic Celestine stricken by an unexpected sense of moral duty prompting her to nail the killer of the child even if she has to marry him to do so; Michel Piccoli's hilarious turn as the eternally insatiable but perennially unsatisfied master of the household who, when his sexual advances towards Celestine are turned down by the latter, has to make do with the ugly-looking house-maid; the aged father-in-law who invites Celestine into his room to read for him, all the while indulging in his foot fetish; the sadistic manservant who thinks nothing of violating and murdering innocent little girls while nurturing dreams of sealing his independence with the purchase of a pub all his own and with Celestine as his partner; the eccentric neighbour who sabotages their garden at every turn and yet yearns for Celestine's companionship, etc. Bunuel offers a typically scathing satire of the bourgeoisie here and, as has already been stated by others in this thread, also shows that he is adept at utilizing the widescreen format despite this being his first and only stab at it, as well as imbuing seemingly trivial and innocent sequences with a subtly perverse touch of subversion.

Even so, I do tend to generally agree with eminent film critic Leslie Halliwell's verdict on this particular film: 'Interesting but not especially successful Bunuel version; the subject is certainly up his street but the novel (by Octave Mirbeau) seems to restrict him'. I found the ending incomprehensible and disappointing myself at first but now I can appreciate not only its irony but its audacity. I have now watched the film three times twice on VHS and once on Criterion's DVD and I must say that it does improve with each viewing.

I don't know if anyone of you has seen Jean Renoir's 1946 US film version but somehow I actually prefer it to Bunuel's. I can't say I concur with Halliwell's review this time around dismissing as it did Renoir's film: 'Hollywood notables were all at sea in this wholly artificial and unpersuasive adaptation of a minor classic'! Leonard Maltin, a well-known US film critic, didn't like it much either saying that it was an 'uneasy attempt at a Continental-style romantic comedy tries hard but never really sure of what it wants to be (the cast) do their best to liven things'! Based on these two capsule reviews I was hardly expecting it to be a patch on the Bunuel version but I nevertheless purchased the PAL VHS (issued by 4 Front but subsequently deleted) since it was quite cheap and, after all, medium Renoir (another of my favorites, by the way) is better than many other film-makers around!

But, surprisingly, what could have easily been a inconsequential and frothy comedy of manners (the result of the typically sanitized Hollywood rewrites of subversive European literature) turned out to be an unprecedented black comedy with that uniquely French bleak outlook of things. Paulette Goddard plays Celestine in this one and she has probably never been better. In fact, as was also the case with the later Bunuel adaptation, the performances here are all first-rate: Hurd Hatfield as the idealistic young son who falls hopelessly in love with Celestine; Judith Anderson as the lady of the house firmly in control of every situation but with some strange alliances of her own; Irene Ryan as a timid scullery maid; Reginald Owen as the weak-willed master of the house perpetually harassed by his wife's demands; and particularly Burgess Meredith (who also wrote the screenplay!) as the half-crazed and shell-shocked retired Army Captain who is their neighbor; but especially Francis Lederer whose portrayal of the devilish manservant Joseph lusting after Celestine while scheming behind the back of his oppressive masters is quite chilling.

Doing some more reading on this film after watching it a couple of times, I found out that there are those who think more highly of Renoir's DIARY OF A CHAMBERMAID than I was previously led to believe. In fact, if I'm not mistaken, no less an authority than Andre' Bazin, in his famous unfinished critical study of Renoir's films, goes so far as to call it a masterpiece and the finest of all the films Renoir made in America between 1941 and 1947. Well, who am I to argue? I do recommend that you seek it out if you have the chance if only to see how it compares with the more readily available Bunuel version.

The thing which struck me most when comparing these two film versions is how different the plot-line actually is from one film to the other. I haven't read the book so I can't say which is the more legitimate one but the differences are quite noteworthy: while there is no child murder in the Renoir version, Joseph does get to kill the eccentric neighbor; there is no handsome young master in Bunuel's version; there is no aged patriarch in Renoir's version; Joseph does not survive to see the realization of his dreams in the Renoir version but rather gets himself slightly killed in a climactic fight in the city streets with Celestine's young pretender, etc. I think it would be a worthwhile exercise if I were to get my hands on Octave Mirbeau's original novel some day!

As a matter of fact, I think a similarly fascinating comparison could be made between (incidentally, another favorite director of mine) Josef von Sternberg's final film with Marlene Dietrich, THE DEVIL IS A WOMAN (1935) and Luis Bunuel's cinematic swan song, CET OBSCUR OBJET DU DESIR aka THAT OBSCURE OBJECT OF DESIRE (1977) both of which were adapted from the same source material: Pierre Louys' 'La Femme Et Le Pantin'.

Don't get me wrong; I do think that LE JOURNAL is an excellent film and would probably be considered a bona-fide masterpiece if it were made by a lesser director. There is much to enjoy in the film: Jeanne Moreau's superb central performance as the opportunistic Celestine stricken by an unexpected sense of moral duty prompting her to nail the killer of the child even if she has to marry him to do so; Michel Piccoli's hilarious turn as the eternally insatiable but perennially unsatisfied master of the household who, when his sexual advances towards Celestine are turned down by the latter, has to make do with the ugly-looking house-maid; the aged father-in-law who invites Celestine into his room to read for him, all the while indulging in his foot fetish; the sadistic manservant who thinks nothing of violating and murdering innocent little girls while nurturing dreams of sealing his independence with the purchase of a pub all his own and with Celestine as his partner; the eccentric neighbour who sabotages their garden at every turn and yet yearns for Celestine's companionship, etc. Bunuel offers a typically scathing satire of the bourgeoisie here and, as has already been stated by others in this thread, also shows that he is adept at utilizing the widescreen format despite this being his first and only stab at it, as well as imbuing seemingly trivial and innocent sequences with a subtly perverse touch of subversion.

Even so, I do tend to generally agree with eminent film critic Leslie Halliwell's verdict on this particular film: 'Interesting but not especially successful Bunuel version; the subject is certainly up his street but the novel (by Octave Mirbeau) seems to restrict him'. I found the ending incomprehensible and disappointing myself at first but now I can appreciate not only its irony but its audacity. I have now watched the film three times twice on VHS and once on Criterion's DVD and I must say that it does improve with each viewing.

I don't know if anyone of you has seen Jean Renoir's 1946 US film version but somehow I actually prefer it to Bunuel's. I can't say I concur with Halliwell's review this time around dismissing as it did Renoir's film: 'Hollywood notables were all at sea in this wholly artificial and unpersuasive adaptation of a minor classic'! Leonard Maltin, a well-known US film critic, didn't like it much either saying that it was an 'uneasy attempt at a Continental-style romantic comedy tries hard but never really sure of what it wants to be (the cast) do their best to liven things'! Based on these two capsule reviews I was hardly expecting it to be a patch on the Bunuel version but I nevertheless purchased the PAL VHS (issued by 4 Front but subsequently deleted) since it was quite cheap and, after all, medium Renoir (another of my favorites, by the way) is better than many other film-makers around!

But, surprisingly, what could have easily been a inconsequential and frothy comedy of manners (the result of the typically sanitized Hollywood rewrites of subversive European literature) turned out to be an unprecedented black comedy with that uniquely French bleak outlook of things. Paulette Goddard plays Celestine in this one and she has probably never been better. In fact, as was also the case with the later Bunuel adaptation, the performances here are all first-rate: Hurd Hatfield as the idealistic young son who falls hopelessly in love with Celestine; Judith Anderson as the lady of the house firmly in control of every situation but with some strange alliances of her own; Irene Ryan as a timid scullery maid; Reginald Owen as the weak-willed master of the house perpetually harassed by his wife's demands; and particularly Burgess Meredith (who also wrote the screenplay!) as the half-crazed and shell-shocked retired Army Captain who is their neighbor; but especially Francis Lederer whose portrayal of the devilish manservant Joseph lusting after Celestine while scheming behind the back of his oppressive masters is quite chilling.

Doing some more reading on this film after watching it a couple of times, I found out that there are those who think more highly of Renoir's DIARY OF A CHAMBERMAID than I was previously led to believe. In fact, if I'm not mistaken, no less an authority than Andre' Bazin, in his famous unfinished critical study of Renoir's films, goes so far as to call it a masterpiece and the finest of all the films Renoir made in America between 1941 and 1947. Well, who am I to argue? I do recommend that you seek it out if you have the chance if only to see how it compares with the more readily available Bunuel version.

The thing which struck me most when comparing these two film versions is how different the plot-line actually is from one film to the other. I haven't read the book so I can't say which is the more legitimate one but the differences are quite noteworthy: while there is no child murder in the Renoir version, Joseph does get to kill the eccentric neighbor; there is no handsome young master in Bunuel's version; there is no aged patriarch in Renoir's version; Joseph does not survive to see the realization of his dreams in the Renoir version but rather gets himself slightly killed in a climactic fight in the city streets with Celestine's young pretender, etc. I think it would be a worthwhile exercise if I were to get my hands on Octave Mirbeau's original novel some day!

As a matter of fact, I think a similarly fascinating comparison could be made between (incidentally, another favorite director of mine) Josef von Sternberg's final film with Marlene Dietrich, THE DEVIL IS A WOMAN (1935) and Luis Bunuel's cinematic swan song, CET OBSCUR OBJET DU DESIR aka THAT OBSCURE OBJECT OF DESIRE (1977) both of which were adapted from the same source material: Pierre Louys' 'La Femme Et Le Pantin'.

A young woman reports to work as a chambermaid at the residence of an eccentric family in the French countryside. Moreau is fine as the maid, a strong-willed woman who attracts the attention of practically every man in the household and neighborhood. Geret as a servant and Piccoli as the testosterone-laden man of the house also turn in notable performances. In one of his more accessible films, Bunuel creates some beautiful imagery with his wide-screen black and white cinematography. However, the script is uneven, with the plot point concerning the rape and murder of a child mixing uneasily with the political and comedic elements. The conclusion is abrupt and unsatisfying.

In the 30's, the witty, literate and quite sophisticated chambermaid Céléstine (Jeanne Moreau) comes from Paris to work for the dysfunctional Monteil family in the country, more specifically for the fetishist on shoes and maniac for cleaning Monsieur Rabour (Jean Ozenne). His daughter and mistress of the house Madame Monteil (Françoise Lugagne) is a frigid and arrogant woman, and her husband, Monsieur Monteil (Michel Piccoli), is a hunter and also a wolf with their maids. Their fascist and rude worker Joseph (Georges Géret) feels a sexual attraction for Céléstine, but she repels him. Their neighbor, Captain Mauger (Daniel Ivernel), has a problem with the Monteils and dumps his garbage in their yard, but Céléstine talks to him and is motive of gossips. When Monsieur Rabour unexpectedly dies, Céléstine quits her job but while in the train station, she finds that the girl Claire was found raped and murdered by the police. Céléstine returns to her job convinced that Joseph killed the little girl and trying to find evidences against him.

"Le Journal d'une Femme de Chambre" is a delightful movie of undefined genre drama, black comedy, adventure? where Luis Buñuel again exposes fight of classes, hypocrisy of both the bourgeois and the working class, a historical moment in France with the fascism growing, the ridiculous role of the clerical and an unsolved murder case. The story is centered in Céléstine, but the motives why a woman with her profile accepts a job in a rural area is never clear. The identity of the rapist and killer of Claire is also not disclosed, there is only a strong insinuation that Joseph killed the girl. The story is very ironic, like for example when Monsieur Monteil is informed that Céléstine and Joseph will marry and requires the sexual favors from Marianne; or the weird fetishism of Monsieur Rabour; or the priest asking for a new roof for the church to Madame Monteil; or the conclusion with Captain Mauger changing his will and serving the mistress and smart Céléstine on their bed. My vote is seven.

Title (Brazil): "O Diário de uma Camareira" ("The Diary of a Chambermaid")

"Le Journal d'une Femme de Chambre" is a delightful movie of undefined genre drama, black comedy, adventure? where Luis Buñuel again exposes fight of classes, hypocrisy of both the bourgeois and the working class, a historical moment in France with the fascism growing, the ridiculous role of the clerical and an unsolved murder case. The story is centered in Céléstine, but the motives why a woman with her profile accepts a job in a rural area is never clear. The identity of the rapist and killer of Claire is also not disclosed, there is only a strong insinuation that Joseph killed the girl. The story is very ironic, like for example when Monsieur Monteil is informed that Céléstine and Joseph will marry and requires the sexual favors from Marianne; or the weird fetishism of Monsieur Rabour; or the priest asking for a new roof for the church to Madame Monteil; or the conclusion with Captain Mauger changing his will and serving the mistress and smart Céléstine on their bed. My vote is seven.

Title (Brazil): "O Diário de uma Camareira" ("The Diary of a Chambermaid")

Bunuel's 'Diary Of A Chambermaid' was released in between two of his surreal masterpieces 'The Exterminating Angel' and 'Simon Of The Desert'. It is, on the surface at least, a lot more conventional as either of those, maybe that's why it doesn't get as much attention as it deserves. I don't know why it is rarely mentioned when people discuss the very best of Bunuel, but for me it's almost as great as 'Viridiana' and 'Belle De Jour'. The story was previously filmed by Renoir in the 1940s, but I haven't seen that version, so I can't say how different Bunuel's approach to the material is. As Bunuel claimed not to have seen it either I don't feel so bad. Jean Moreau, the beautiful star of Truffaut's 'Jules And Jim' and countless other Euro art film favourites, gives a brilliant performance as the enigmatic Celestine, maid to The Monteils, a very odd family living in pre-War France. Bunuel includes some of his usual comments about sexual deviance, and France's future under the Nazi occupation haunts the whole film, but what is most interesting to me about the picture is its subtlety and ambiguity. Like 'Belle De Jour' I think each repeated viewing will reveal more, and opinions on its meaning will depend on the individual viewer. Personally I'm still exploring Bunuel's extraordinary body of work. It is exciting doing so. I've probably only seen a third of his output so far, but I've yet to see a movie made by him that is less than fascinating. 'Diary Of A Chambermaid' just might be his most underrated film. I highly recommend it.

Buñuel once said, "Bourgeois morality is for me immoral and to be fought. The morality founded on our most unjust social institutions, like religion, patriotism, the family, culture: briefly, what are called 'the pillars of society'."

I mention this, not to alienate people who might find such a statement offensive, but to suggest insight into his point of view. A viewpoint vigorously defended in this anti-bourgeois, rural tale that has a kick like a mule. Buñuel's truths are just as applicable today but, by putting them in 1930s France, he sweetens the bitter pill with a coating of sex, storytelling and the reassuring fiction that 'things have maybe moved on since then.'

Célestine impresses us. Intelligent, attractive and sophisticated - but she nevertheless needs to earn her living in service. She takes the train from Paris to work as a chambermaid at a country estate. In this lap of wealth, she deals with a panoply of dodgy people. A brutish handyman. A frigidly overbearing Madame Monteil. Madame's lecherous husband and her kinky father. Remarkably, none of these are portrayed as stereotypes. Characters are well fleshed out as Buñuel pits one against another. Madame Monteil earns our sympathy as she confides sexual shortcomings to the priest, who is in turn well-meaning if hopelessly out of touch. Doddering old Monsieur Rabour, although at first shockingly abhorrent with his fixation on women's feet, probably has nothing more harmful than a shoe fetish. "Would you mind if I touch your calf?" he asks (but goes no further up her leg). Is Célestine playing a dangerous game? Is she a libertine? Or just one step ahead of her audience?

The first half of Diary of a Chambermaid is delightful saucy comedy. Buñuel's famed surrealism, that make films like Un Chien Andalou or L'Âge d'Or so formidable, is nowhere to be seen. Nor do we have to grapple with the distanciation of Exterminating Angel, his Brechtian masterpiece of just two years earlier. But be warned, gentle reader. The second half is not only grislier, but by the end Buñuel will have pulled the rug from under your feet. It can be a bleak experience.

Quite apart from a clever story, Diary of a Chambermaid offers many delights, both to casual viewers and serious film analysts. Depending on your viewpoint, Moreau's many-sided performance is either a triumph for feminism or stands feminism on its head. It strips bare the bourgeoisie and capitalist, presenting the rising tide of French fascism as xenophobic intolerance - one we can recognise as replicated in many countries or patriotic cults even today. The hypocrisy of the upper classes is one of 'fur coat and no knickers'; whereas the pious protestations of the lower ranks are shown as the facade from which they lust after the coat itself.

Class-struggle is mirrored by sex-as-power. To men, sex becomes a celebration of might, whether physical, social or financial. To women, it is the potential to entrap with allure. She is always present and always unattainable. Through this implied promise of sexual gratification she bends men to her will. And still projects an aura of 'purity'. Our handyman tortures a goose before killing it rather horrible, but in a way does it add to his raw animal charm? And is Buñuel really just telling a story? Or is he manipulating his audience to drive the point home?

This is also Buñuel's only film made in anamorphic widescreen format. Although not showy, the cinematography is powerful. Credits open to the sound of a rushing steam train. We watch, through Célestine's eyes, the countryside flash by. A wide angle lens increases the sense of movement, as if we are propelled by an unstoppable force.

When Joseph tries to kiss Célestine at night by the bonfire, his posture is that of a vampire. A snail crawling across the a dead and violated body in the woods is as vivid and shocking as anything from Buñuel's earlier catalogue of slit eyeballs and dead donkeys. But it is Buñuel's acerbic vision of all that is wrong, in all layers of society, that is so chilling.

At one point, Monsieur Rabour is reading the French author JK Huysmans. Huysman's view of the world was as pessimistic as Buñuel, but it is Buñuel that makes it so all-encompassing. The festering fascist mob who cheer for Chiappe in our film, are honouring the same chief of police who prohibited Buñuel's L'Âge d'Or (after fascists destroyed the cinema where it was being shown). There were few governments that liked Buñuel, and we can see that the feeling was mutual.

The film is more political than it is entertaining, which may alienate some viewers who start off liking it. Even the title seems cynical I don't recall any suggestion of her keeping a journal. Diary of a Chambermaid is a great vehicle for Moreau, who gets to play so many characters in one. A criticism often levelled at mainstream cinema is that women tend to be decoration in male-driven plots. Célestine (or 'Marie' as she is called in another dig at Catholic - or class - depersonalisation) doesn't so much take over the driving seat as suggest a new perspective from which she is in control. Audiences will divide on whether they ultimately like her or not.

Things may have moved on. Domestic service is less harsh in most parts of the world where it survives today. Fascism has been replaced with virulent if not yet such obvious forms of rampant and aggressive nationalism. Sex is not always a game of power. But forces of immorality still pose in white robes and high office. 'Commoners' still aspire to the evils they decry. The purity of a saint is maybe needed to 'enjoy' Diary of a Chambermaid. But Buñuel stood up for his beliefs. Today, most viewers may content themselves with standing up for his cinematic skills.

I mention this, not to alienate people who might find such a statement offensive, but to suggest insight into his point of view. A viewpoint vigorously defended in this anti-bourgeois, rural tale that has a kick like a mule. Buñuel's truths are just as applicable today but, by putting them in 1930s France, he sweetens the bitter pill with a coating of sex, storytelling and the reassuring fiction that 'things have maybe moved on since then.'

Célestine impresses us. Intelligent, attractive and sophisticated - but she nevertheless needs to earn her living in service. She takes the train from Paris to work as a chambermaid at a country estate. In this lap of wealth, she deals with a panoply of dodgy people. A brutish handyman. A frigidly overbearing Madame Monteil. Madame's lecherous husband and her kinky father. Remarkably, none of these are portrayed as stereotypes. Characters are well fleshed out as Buñuel pits one against another. Madame Monteil earns our sympathy as she confides sexual shortcomings to the priest, who is in turn well-meaning if hopelessly out of touch. Doddering old Monsieur Rabour, although at first shockingly abhorrent with his fixation on women's feet, probably has nothing more harmful than a shoe fetish. "Would you mind if I touch your calf?" he asks (but goes no further up her leg). Is Célestine playing a dangerous game? Is she a libertine? Or just one step ahead of her audience?

The first half of Diary of a Chambermaid is delightful saucy comedy. Buñuel's famed surrealism, that make films like Un Chien Andalou or L'Âge d'Or so formidable, is nowhere to be seen. Nor do we have to grapple with the distanciation of Exterminating Angel, his Brechtian masterpiece of just two years earlier. But be warned, gentle reader. The second half is not only grislier, but by the end Buñuel will have pulled the rug from under your feet. It can be a bleak experience.

Quite apart from a clever story, Diary of a Chambermaid offers many delights, both to casual viewers and serious film analysts. Depending on your viewpoint, Moreau's many-sided performance is either a triumph for feminism or stands feminism on its head. It strips bare the bourgeoisie and capitalist, presenting the rising tide of French fascism as xenophobic intolerance - one we can recognise as replicated in many countries or patriotic cults even today. The hypocrisy of the upper classes is one of 'fur coat and no knickers'; whereas the pious protestations of the lower ranks are shown as the facade from which they lust after the coat itself.

Class-struggle is mirrored by sex-as-power. To men, sex becomes a celebration of might, whether physical, social or financial. To women, it is the potential to entrap with allure. She is always present and always unattainable. Through this implied promise of sexual gratification she bends men to her will. And still projects an aura of 'purity'. Our handyman tortures a goose before killing it rather horrible, but in a way does it add to his raw animal charm? And is Buñuel really just telling a story? Or is he manipulating his audience to drive the point home?

This is also Buñuel's only film made in anamorphic widescreen format. Although not showy, the cinematography is powerful. Credits open to the sound of a rushing steam train. We watch, through Célestine's eyes, the countryside flash by. A wide angle lens increases the sense of movement, as if we are propelled by an unstoppable force.

When Joseph tries to kiss Célestine at night by the bonfire, his posture is that of a vampire. A snail crawling across the a dead and violated body in the woods is as vivid and shocking as anything from Buñuel's earlier catalogue of slit eyeballs and dead donkeys. But it is Buñuel's acerbic vision of all that is wrong, in all layers of society, that is so chilling.

At one point, Monsieur Rabour is reading the French author JK Huysmans. Huysman's view of the world was as pessimistic as Buñuel, but it is Buñuel that makes it so all-encompassing. The festering fascist mob who cheer for Chiappe in our film, are honouring the same chief of police who prohibited Buñuel's L'Âge d'Or (after fascists destroyed the cinema where it was being shown). There were few governments that liked Buñuel, and we can see that the feeling was mutual.

The film is more political than it is entertaining, which may alienate some viewers who start off liking it. Even the title seems cynical I don't recall any suggestion of her keeping a journal. Diary of a Chambermaid is a great vehicle for Moreau, who gets to play so many characters in one. A criticism often levelled at mainstream cinema is that women tend to be decoration in male-driven plots. Célestine (or 'Marie' as she is called in another dig at Catholic - or class - depersonalisation) doesn't so much take over the driving seat as suggest a new perspective from which she is in control. Audiences will divide on whether they ultimately like her or not.

Things may have moved on. Domestic service is less harsh in most parts of the world where it survives today. Fascism has been replaced with virulent if not yet such obvious forms of rampant and aggressive nationalism. Sex is not always a game of power. But forces of immorality still pose in white robes and high office. 'Commoners' still aspire to the evils they decry. The purity of a saint is maybe needed to 'enjoy' Diary of a Chambermaid. But Buñuel stood up for his beliefs. Today, most viewers may content themselves with standing up for his cinematic skills.

क्या आपको पता है

- ट्रिवियाThis is Luis Buñuel's only film in the anamorphic widescreen format.

- गूफ़At the train station, Célestine is supposed to be returning to Paris but she's waiting on the wrong side of the tracks: In one shot, one can clearly read "Direction Paris" on the other side.

- कनेक्शनFeatured in A propósito de Buñuel (2000)

टॉप पसंद

रेटिंग देने के लिए साइन-इन करें और वैयक्तिकृत सुझावों के लिए वॉचलिस्ट करें

- How long is Diary of a Chambermaid?Alexa द्वारा संचालित

विवरण

बॉक्स ऑफ़िस

- दुनिया भर में सकल

- $126

- चलने की अवधि

- 1 घं 37 मि(97 min)

- रंग

- ध्वनि मिश्रण

- पक्ष अनुपात

- 2.35 : 1

इस पेज में योगदान दें

किसी बदलाव का सुझाव दें या अनुपलब्ध कॉन्टेंट जोड़ें