IMDb रेटिंग

7.1/10

2.2 हज़ार

आपकी रेटिंग

अपनी भाषा में प्लॉट जोड़ेंTriangle story: painter, his young male model, unscrupulous princess.Triangle story: painter, his young male model, unscrupulous princess.Triangle story: painter, his young male model, unscrupulous princess.

- निर्देशक

- लेखक

- स्टार

Mady Christians

- Frau

- (बिना क्रेडिट के)

फ़ीचर्ड समीक्षाएं

A famous painter named Claude Zoret (Benjamin Christensen) falls in love with one of his models, Michael (Walter Slezak), and for a time the two live happily as partners. Zoret is considerably older than Michael, and as they age, Michael begins to drift from him, although Zoret is completely blind to this.

Directed by the great Danish director Carl Theodor Dreyer, who went on to direct "The Passion of Joan of Arc", called by some "the most influential film of all time". Written by Dreyer, and Thea von Harbou, who is now probably best known as Fritz Lang's wife. Produced by Erich Pommer, which cinematography by Karl Freund. As far as 1920s German cinema goes, this is top drawer.

Along with "Different From the Others" (1919) and "Sex in Chains" (1928), "Michael" is widely considered a landmark in gay silent cinema. It has also been suggested that the film reflects personal feelings harbored by Dreyer after a purported homosexual affair, though I have no evidence of that.

This film was pretty great, despite being silent and foreign. Those factors took nothing away from the experience for me, and I have to give credit to Dreyer and the cast -- the film is full of very intense faces, which made up for the lack of any audible emotion.

What drew me to this film was having cameraman Karl Freund on camera. A genius behind it, this is a rare treat to see the man in front and caught on film. His role is fairly small, but captures his movements and body language in a way that no photograph ever could. To my knowledge, this was his last acting role in a film.

The film has been cited to have influenced several directors. Alfred Hitchcock drew upon motifs from "Michael" for his script for "The Blackguard" (1925).

Directed by the great Danish director Carl Theodor Dreyer, who went on to direct "The Passion of Joan of Arc", called by some "the most influential film of all time". Written by Dreyer, and Thea von Harbou, who is now probably best known as Fritz Lang's wife. Produced by Erich Pommer, which cinematography by Karl Freund. As far as 1920s German cinema goes, this is top drawer.

Along with "Different From the Others" (1919) and "Sex in Chains" (1928), "Michael" is widely considered a landmark in gay silent cinema. It has also been suggested that the film reflects personal feelings harbored by Dreyer after a purported homosexual affair, though I have no evidence of that.

This film was pretty great, despite being silent and foreign. Those factors took nothing away from the experience for me, and I have to give credit to Dreyer and the cast -- the film is full of very intense faces, which made up for the lack of any audible emotion.

What drew me to this film was having cameraman Karl Freund on camera. A genius behind it, this is a rare treat to see the man in front and caught on film. His role is fairly small, but captures his movements and body language in a way that no photograph ever could. To my knowledge, this was his last acting role in a film.

The film has been cited to have influenced several directors. Alfred Hitchcock drew upon motifs from "Michael" for his script for "The Blackguard" (1925).

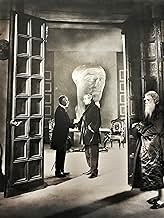

Silent films are a purely visual medium, and fittingly, it's the visuals that first catch our eye, and that arguably received the most attention in 'Michael.' The production design and art direction are outstanding. The sets are flush with fetching design and decoration, immediately standing out from the opening scene onward and inculcating a definite feeling of art and luxury. Hugo Häring's costume design is wonderful, quietly vibrant and handily matching the surroundings. If to a lesser extent, even the hair and makeup work is distinct and notable. And on top of all this, Karl Freund and Rudolph Maté's cinematography remains crisp and vivid almost 100 years later, allowing every detail to pop out; clearly the effort to preserve the title has been very successful. Factor in some careful, precise shot composition by director Carl Theodor Dreyer, and one can only praise the craft of the feature as rich and satisfying.

There's a surprising trend toward nuance in the performances here. Much of the silent era was characterized by acting in the style of stage plays, with exaggerated body language and facial expressions to compensate for the lack of sound or spoken dialogue. In 'Michael,' it seems to me like the cast tend to strike a balance. Very often the faintest shift in their comportment is all that is necessary to communicate the thoughts and feelings of their roles, and it's a pleasure to watch, especially as it would be a few more years before cinema at large leaned the same way. No one actor here stands out, but they all fill their parts very capably.

The drift toward subtlety doesn't entirely work in the movie's favor, however. Fine as the screenplay is, the personalities and complexities of characters are generally so subdued that one could be forgiven for thinking that they haven't any at all. Dialogue as related through intertitles is suitable but unremarkable as it advances the plot. The scene writing that dictates the arrangement and flow of any given moment, and instructs the cast as such, is the most actively engaging aspect of 'Michael' as the whole is built bit by bit. The overall narrative is duly engaging for the interpersonal drama within, but that's all the more that can be truly said of it. There are prominent themes of unrequited love. There are LGBTQ themes running throughout, too, but they are so heavily downplayed (for good reason, in fairness; see Paragraph 175) that they're all but undetectable without the aid of outside analysis.

Lush visuals greet us, and a story is imparted - but as we watch, it's not a story that especially conveys the weight and impact of the course of events as characters feel them. It mostly just is. That's deeply unfortunate, because though sorrowful, there are great ideas here that should most certainly inspire emotional investment in viewers. It seems to me that the utmost heart of the production is somehow restrained, diminishing the value of the experience. Only near the very end do I sense any particular spark; I want to like it more than I do, but this title simply doesn't strike a chord with me in the way that other silent classics have.

Perhaps I would get more out of 'Michael,' as others surely have, if I were to watch it again. I definitely think it's worth watching - only, I don't see it as being an essential piece of film in the way that other pictures are. The sharpest story beats are sadly dulled, and those less significant rounding details that first greeted us are in fact what most leaves an impression - but all the same, if you have the chance to watch 'Michael,' these are 95 minutes that still hold up fairly well.

There's a surprising trend toward nuance in the performances here. Much of the silent era was characterized by acting in the style of stage plays, with exaggerated body language and facial expressions to compensate for the lack of sound or spoken dialogue. In 'Michael,' it seems to me like the cast tend to strike a balance. Very often the faintest shift in their comportment is all that is necessary to communicate the thoughts and feelings of their roles, and it's a pleasure to watch, especially as it would be a few more years before cinema at large leaned the same way. No one actor here stands out, but they all fill their parts very capably.

The drift toward subtlety doesn't entirely work in the movie's favor, however. Fine as the screenplay is, the personalities and complexities of characters are generally so subdued that one could be forgiven for thinking that they haven't any at all. Dialogue as related through intertitles is suitable but unremarkable as it advances the plot. The scene writing that dictates the arrangement and flow of any given moment, and instructs the cast as such, is the most actively engaging aspect of 'Michael' as the whole is built bit by bit. The overall narrative is duly engaging for the interpersonal drama within, but that's all the more that can be truly said of it. There are prominent themes of unrequited love. There are LGBTQ themes running throughout, too, but they are so heavily downplayed (for good reason, in fairness; see Paragraph 175) that they're all but undetectable without the aid of outside analysis.

Lush visuals greet us, and a story is imparted - but as we watch, it's not a story that especially conveys the weight and impact of the course of events as characters feel them. It mostly just is. That's deeply unfortunate, because though sorrowful, there are great ideas here that should most certainly inspire emotional investment in viewers. It seems to me that the utmost heart of the production is somehow restrained, diminishing the value of the experience. Only near the very end do I sense any particular spark; I want to like it more than I do, but this title simply doesn't strike a chord with me in the way that other silent classics have.

Perhaps I would get more out of 'Michael,' as others surely have, if I were to watch it again. I definitely think it's worth watching - only, I don't see it as being an essential piece of film in the way that other pictures are. The sharpest story beats are sadly dulled, and those less significant rounding details that first greeted us are in fact what most leaves an impression - but all the same, if you have the chance to watch 'Michael,' these are 95 minutes that still hold up fairly well.

Mikaël / Michael (1924) :

Brief Review -

95 Years Before the French Classic Portrait of a Lady on Fire. Carl Theodor Dreyer's gutsy German silent classic on the conflict between homosexuality and bisexuality. Watching a French classic like Portrait of a Lady on Fire in 2019 left me stunned with its uncut version of storytelling. A lesbian romance through the lens of art. And then today I bumped into Carl Theodor Dreyer's gutsy silent drama, Michael, which painted this mixed portrait almost 95 years ago. I am not sure what word or adjective I should use for this film if I have already used 'stunned' for Céline Sciamma's French drama. Speechless.. yes, I think that's the word. Michael is a rare mix of pathbreaking cinema and taboo-breaking cinema, working in the same factory. Dreyer's silent film was way ahead of its time, and it still feels that way today. It is rightly regarded as a watershed moment in "gay" silent cinema. I'm not saying that it's just about homosexuality and bisexuality, but the way it sees that intricate romance through the lenses of art, i.e., painting, is what I loved the most. I liked Portrait of a Lady on Fire for the same reason. Based on Herman Bang's novel, Michael is a love triangle between a painter, Zoret, his young male model, Michael, and an unscrupulous princess, Zamikow, who takes away Michael. There is another love triangle involved, but let's keep it a secret here. Michael is content-driven and high-concept cinema as it tackles taboo issues like gender attraction, love, and money. While doing so, it does not forget to use the artistic values of a primary art medium, painting. Carl Theodor Dreyer pulls the best out of his actors while he himself gives out everything he has as a director. Dreyer's film sets benchmarks for the early stages of pathbreaking cinema when society was not ready to accept such things. A must-see for content lovers.

RATING - 8/10*

By - #samthebestest.

95 Years Before the French Classic Portrait of a Lady on Fire. Carl Theodor Dreyer's gutsy German silent classic on the conflict between homosexuality and bisexuality. Watching a French classic like Portrait of a Lady on Fire in 2019 left me stunned with its uncut version of storytelling. A lesbian romance through the lens of art. And then today I bumped into Carl Theodor Dreyer's gutsy silent drama, Michael, which painted this mixed portrait almost 95 years ago. I am not sure what word or adjective I should use for this film if I have already used 'stunned' for Céline Sciamma's French drama. Speechless.. yes, I think that's the word. Michael is a rare mix of pathbreaking cinema and taboo-breaking cinema, working in the same factory. Dreyer's silent film was way ahead of its time, and it still feels that way today. It is rightly regarded as a watershed moment in "gay" silent cinema. I'm not saying that it's just about homosexuality and bisexuality, but the way it sees that intricate romance through the lenses of art, i.e., painting, is what I loved the most. I liked Portrait of a Lady on Fire for the same reason. Based on Herman Bang's novel, Michael is a love triangle between a painter, Zoret, his young male model, Michael, and an unscrupulous princess, Zamikow, who takes away Michael. There is another love triangle involved, but let's keep it a secret here. Michael is content-driven and high-concept cinema as it tackles taboo issues like gender attraction, love, and money. While doing so, it does not forget to use the artistic values of a primary art medium, painting. Carl Theodor Dreyer pulls the best out of his actors while he himself gives out everything he has as a director. Dreyer's film sets benchmarks for the early stages of pathbreaking cinema when society was not ready to accept such things. A must-see for content lovers.

RATING - 8/10*

By - #samthebestest.

Famous painter Claude Zoret (Benjamin Christensen) is in love with friend, muse, and model Michael (Walter Slezak). They live comfortably and happily in their mansion, which is littered with Zoret's pieces with Michael as their inspiration. When the bankrupt Countess Lucia Zamikoff (Nora Gregor) comes to visit to ask Zoret to paint her, Zoret accepts but struggles to put any life into his painting. He can't depict her eyes, but Michael steps in and completes the painting. Sensing his infatuation with her, the Countess seduces Michael, and Zoret witnesses his relationship become more and more distant. Michael steals and sells Zoret's sketches and paintings in order to satisfy the Countess' spending habits, and Zoret eventually falls ill.

Although it's hardly tackled explicitly, and more suggested in looks, exchanges, and title-cards than sexual imagery, Michael's tackling of homosexuality was quite revolutionary in its day. Naturally, it failed financially and critically (although when Dreyer made The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928) and became auteur, it has since been re-visited and praised), but it should be a film that any cinephile should see, especially those with an interest in the origins of Queer Cinema and the depiction of homosexuality in film. Benjamin Christensen, perhaps best known as director of the silent docu-horror masterpiece Haxan (1922), is masterful as Zoret, his face darkened with sadness, subtle jealousy, and tragic sentiment. Slazek and Gregor fair less well, and suffer in comparison to Christensen's depiction.

Although the climax is predictable, it has a feeling of inevitably which makes it fittingly moving and quite beautiful, similar in many ways to the ending of Dreyer's Ordet (1955). But the film is surprisingly rich and luscious, with Dreyer's usual blank canvas and bleak settings replaced by detailed sets, all captured by cinematographer's Rudolph Mate and Karl Freund (who appears here as art dealer Le Blanc, and would go on to work on some Universal's finest horror output in the 1930's). A wonderful, 'minor' work in Dreyer's wealthy filmography.

www.the-wrath-of-blog.blogspot.com

Although it's hardly tackled explicitly, and more suggested in looks, exchanges, and title-cards than sexual imagery, Michael's tackling of homosexuality was quite revolutionary in its day. Naturally, it failed financially and critically (although when Dreyer made The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928) and became auteur, it has since been re-visited and praised), but it should be a film that any cinephile should see, especially those with an interest in the origins of Queer Cinema and the depiction of homosexuality in film. Benjamin Christensen, perhaps best known as director of the silent docu-horror masterpiece Haxan (1922), is masterful as Zoret, his face darkened with sadness, subtle jealousy, and tragic sentiment. Slazek and Gregor fair less well, and suffer in comparison to Christensen's depiction.

Although the climax is predictable, it has a feeling of inevitably which makes it fittingly moving and quite beautiful, similar in many ways to the ending of Dreyer's Ordet (1955). But the film is surprisingly rich and luscious, with Dreyer's usual blank canvas and bleak settings replaced by detailed sets, all captured by cinematographer's Rudolph Mate and Karl Freund (who appears here as art dealer Le Blanc, and would go on to work on some Universal's finest horror output in the 1930's). A wonderful, 'minor' work in Dreyer's wealthy filmography.

www.the-wrath-of-blog.blogspot.com

This is a beautiful film, in its rich mise-en-scène and gorgeous cinematography. It resembles in polished photography, including how well it has remained over the years, the better-looking Hollywood films at the end of the silent era. The lighting is great, creating a very clear and crisp picture, with many subtle effects. And, the interior furnishings are lush.

"Michael" is a moving film, and I think that has more to do with the photography and settings than with the drama. The implicit homosexual relationship between the artist and his model, Michael, is curious, though. What I especially like about the narrative, however, is that it's about art--a very apt subject, which is heightened by the photography. Benjamin Christensen plays the aging artist, which is a significant casting decision, given that he was the great Danish filmmaker to precede Dreyer. Christensen had worked as an actor in his own films, so he's fully capable in this role. Additionally, cinematographer Karl Freund, who changed the role of the camera the same year in "The Last Laugh", has a small role as an art dealer.

Overall, Dreyer does better here with the actors than he previously had. He achieves a nice pacing, as well, except for a few mistimed editing cues, which are too quick. Even the subplot, for mood affect, works. It's a mature work--probably his first--resembling his later films in many ways.

"Michael" is a moving film, and I think that has more to do with the photography and settings than with the drama. The implicit homosexual relationship between the artist and his model, Michael, is curious, though. What I especially like about the narrative, however, is that it's about art--a very apt subject, which is heightened by the photography. Benjamin Christensen plays the aging artist, which is a significant casting decision, given that he was the great Danish filmmaker to precede Dreyer. Christensen had worked as an actor in his own films, so he's fully capable in this role. Additionally, cinematographer Karl Freund, who changed the role of the camera the same year in "The Last Laugh", has a small role as an art dealer.

Overall, Dreyer does better here with the actors than he previously had. He achieves a nice pacing, as well, except for a few mistimed editing cues, which are too quick. Even the subplot, for mood affect, works. It's a mature work--probably his first--resembling his later films in many ways.

क्या आपको पता है

- ट्रिवियाGrete Mosheim's debut.

- गूफ़When the painter Claude Zoret is talking to Mikael's creditor he switches from standing up to sitting down back to standing up between shots.

- भाव

[first lines]

Motto (titlecard): Motto: Now I can die in peace for I have known a great love.

- इसके अलावा अन्य वर्जनIn 2004, Kino International Corporation copyrighted a version with a piano score compiled and performed by Neal Kurz. It was produced for video by David Shepard and runs 86 minutes.

- कनेक्शनFeatured in Carl Th. Dreyer (1966)

टॉप पसंद

रेटिंग देने के लिए साइन-इन करें और वैयक्तिकृत सुझावों के लिए वॉचलिस्ट करें

- How long is Michael?Alexa द्वारा संचालित

विवरण

- चलने की अवधि1 घंटा 33 मिनट

- ध्वनि मिश्रण

- पक्ष अनुपात

- 1.33 : 1

इस पेज में योगदान दें

किसी बदलाव का सुझाव दें या अनुपलब्ध कॉन्टेंट जोड़ें