IMDb रेटिंग

6.8/10

8 हज़ार

आपकी रेटिंग

अपनी भाषा में प्लॉट जोड़ेंWorkers leaving the Lumière factory for lunch in Lyon, France in 1895; a place of great photographic innovation and one of the birth places of cinema.Workers leaving the Lumière factory for lunch in Lyon, France in 1895; a place of great photographic innovation and one of the birth places of cinema.Workers leaving the Lumière factory for lunch in Lyon, France in 1895; a place of great photographic innovation and one of the birth places of cinema.

- निर्देशक

फ़ीचर्ड समीक्षाएं

For almost anyone with an interest in the earliest motion pictures, watching this footage of workers leaving the Lumière factory never gets old. Its historical significance, as the first movie that Louis Lumière showed at the first public demonstration of his cinematograph, would certainly make it well worth remembering for that reason alone. But beyond Lumière's visionary and technical abilities, he also had a knack for choosing material for his features that was interesting in itself.

This particular subject could not have been more appropriate for his first public presentation. The seemingly simple footage is almost a microcosm of the new world created by cinema. The widely varying reactions of the various workers (not to mention the occasional dog) contain almost every common reaction to the camera: some are curious and don't mind showing it, some are curious and pretend not to be, some are a little uncomfortable, some seem to be fascinated by having their picture taken. With the 'cast' as large as it is, you can watch the film a good number of times and still not lose interest.

Beyond that, the way that the camera field is set up shows an innate sense of the value of movement, particularly movement towards the camera, in holding the attention of the audience. Some of Lumière's best films made further use of this idea.

In one very short movie, this film preserves an important step in cinema history, while also containing material that, in a sense, portrays and foresees many of the future effects of the Lumière brothers' invention. That we can experience both, any time that we view this footage of these long-past men and women and their honest reactions to the camera, is still fascinating.

This particular subject could not have been more appropriate for his first public presentation. The seemingly simple footage is almost a microcosm of the new world created by cinema. The widely varying reactions of the various workers (not to mention the occasional dog) contain almost every common reaction to the camera: some are curious and don't mind showing it, some are curious and pretend not to be, some are a little uncomfortable, some seem to be fascinated by having their picture taken. With the 'cast' as large as it is, you can watch the film a good number of times and still not lose interest.

Beyond that, the way that the camera field is set up shows an innate sense of the value of movement, particularly movement towards the camera, in holding the attention of the audience. Some of Lumière's best films made further use of this idea.

In one very short movie, this film preserves an important step in cinema history, while also containing material that, in a sense, portrays and foresees many of the future effects of the Lumière brothers' invention. That we can experience both, any time that we view this footage of these long-past men and women and their honest reactions to the camera, is still fascinating.

Even as the first film to come to cinema, it's still better than a lot of the films that come out today. The origin story of this film is completely fascinating. An unknowing audience attend the cinema assuming it will be a series of still images, until they get hit with the greatest twist of all time - a moving picture. The 33/100 who went to see this film are some of the luckiest people of all time, just imagine their shock.......

This 50-or-so-seconds-long film has held a special place in movie history for being the first of ten 50-or-so-seconds-long films to be shown to a paying audience at the Grand Café in Paris on 28 December 1895. This wasn't the first commercial exhibition of cinema; the Skladanosky brothers, for example, had accomplished the feat with their Bioscope nearly two months prior. Still earlier, Charles Francis Jenkins and Thomas Armat projected films to a paying audience as early as September 1895. There were also the Lathams, whose experiments in projection were aided by William K.L. Dickson, who was still employed by Thomas Edison at the time. Some historians have made even earlier claims for others. If animated pictures on discs or other non-celluloid materials are included, another host of precedents can be added. Nevertheless, this showing by the Lumière brothers changed the world. It and subsequent presentations were exceedingly popular, and the projection of the films and the films themselves displayed technological and aesthetic advancement over previous equipment and pictures.

We now know that the Lumière brothers made at least three versions of "Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory", because these exist today. Until recently, however, it was generally believed that there was only one version. In the 1940s, Louis Lumière claimed to have made it once; he also misremembered the approximate date he filmed it. He likely made the three films separately between 19 May 1895 and August 1986. The brothers projected the first version (the one-horse version) at their first private screening on 22 May 1895. The second version (two horses) is the one that appeared on the screen on 28 December 1895. The final version (with no horses) was long believed (still confused to be by some) to be the first film and is still more widely distributed than the others. (For all three versions with the best quality transfer available, see "The Lumière Brothers' First Films" (1996).)

The light weight of the Lumière Cinématographe, as opposed to the bulky and generally immobile Kinetograph, allowed the Lumière brothers to create a new genre with their actuality films (a genre that, at least for a while, was probably more popular than the earliest fictional story films). Moreover, other advancements made for crisper and steadier films (although contemporaries complained of excessive flickering). The Lumière brothers would consequently be the firsts to largely decide the framing for their subjects. In this one of workers leaving the factory, the framing is essentially a perpendicular long take of the action. It's not quite as interesting as, say, the diagonal framing in "L'Arrivée d'un train" (1896), but the action here doesn't call for it. The camera is also stationary, but one of the Lumière filmmakers, Alexandre Promio, would change that by the following year, such as in "Panorama du Grand Canal vu d'un bateau".

"Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory" is the first so-called "actuality" film, a proto-documentary genre of early cinema. It is simply a film, as its title implies, of workers exiting the Lumière photographic factory in Lyons to passing out of frame to either side. Its major spectacle is that there's movement--projected on a screen. These actuality films were very popular, for the natural and realistic settings, the variety of subjects that were available, as well as the superior picture quality of the Cinématographe films. This prompted the Edison Company to create their own actuality films, in addition to improving their camera and, eventually, moving to the projection of cinema. Other early filmmakers, like Robert W. Paul and Georges Méliès, would also begin making films within the actuality genre. Yet, today, it seems apparent that this film and many other so-called actualités are directed--events have been manipulated. The camera is not an invisible recorder; it influences. "L'Arrivée d'un train" and some other actuality films do appear to be undirected, though; some even achieve the metaphoric invisibility of the camera (Louis Le Prince's "Traffic Crossing Leeds Bridge" (1888) appears to accomplish it).

Reportedly (including by Méliès), when this film was projected to audiences, the projectionist would temporarily freeze the first frame and then amaze audiences by running the motion picture. Méliès later said of this: "I must admit we were all stupefied as you can understand. I immediately said, 'That's for me. What an extraordinary thing.'"

On an interesting side note, the first projectionist of these showings was Charles Moisson, who also introduced the Lumière's to film, helped them invent the Cinématographe and made some of the company's earlier films. With Francis Doublier (who claims to appear in "Leaving the Lumière Factory"), they photographed the coronation of Tsar Nikolas II, which ended in tragedy when a stand gave way and thousands of people were trampled to death in an ensuing panic. Russian authorities confiscated the film, and it was never seen again. On the issue of actuality films, this was a dramatic example of the camera as a relative non-participant of events.

Anyhow, this film, "Leaving the Lumière Factory", is an important landmark in film history, for not only introducing many to cinema, but also for introducing, through their actuality films, a new way of seeing. Within and without the frame, the gates were opened.

(Note: This is the fifth in a series of my comments on 10 "firsts" in film history. The other films covered are Traffic Crossing Leeds Bridge (1888), Blacksmith Scene (1893), Annabelle Serpentine Dance (1895), The Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots (1895), L'Arroseur arose (1895), L'Arrivée d'un train à La Ciotat (1896), Panorama du Grand Canal vu d'un bateau (1896), Return of Lifeboat (1897) and Panorama of Eiffel Tower (1900).)

We now know that the Lumière brothers made at least three versions of "Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory", because these exist today. Until recently, however, it was generally believed that there was only one version. In the 1940s, Louis Lumière claimed to have made it once; he also misremembered the approximate date he filmed it. He likely made the three films separately between 19 May 1895 and August 1986. The brothers projected the first version (the one-horse version) at their first private screening on 22 May 1895. The second version (two horses) is the one that appeared on the screen on 28 December 1895. The final version (with no horses) was long believed (still confused to be by some) to be the first film and is still more widely distributed than the others. (For all three versions with the best quality transfer available, see "The Lumière Brothers' First Films" (1996).)

The light weight of the Lumière Cinématographe, as opposed to the bulky and generally immobile Kinetograph, allowed the Lumière brothers to create a new genre with their actuality films (a genre that, at least for a while, was probably more popular than the earliest fictional story films). Moreover, other advancements made for crisper and steadier films (although contemporaries complained of excessive flickering). The Lumière brothers would consequently be the firsts to largely decide the framing for their subjects. In this one of workers leaving the factory, the framing is essentially a perpendicular long take of the action. It's not quite as interesting as, say, the diagonal framing in "L'Arrivée d'un train" (1896), but the action here doesn't call for it. The camera is also stationary, but one of the Lumière filmmakers, Alexandre Promio, would change that by the following year, such as in "Panorama du Grand Canal vu d'un bateau".

"Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory" is the first so-called "actuality" film, a proto-documentary genre of early cinema. It is simply a film, as its title implies, of workers exiting the Lumière photographic factory in Lyons to passing out of frame to either side. Its major spectacle is that there's movement--projected on a screen. These actuality films were very popular, for the natural and realistic settings, the variety of subjects that were available, as well as the superior picture quality of the Cinématographe films. This prompted the Edison Company to create their own actuality films, in addition to improving their camera and, eventually, moving to the projection of cinema. Other early filmmakers, like Robert W. Paul and Georges Méliès, would also begin making films within the actuality genre. Yet, today, it seems apparent that this film and many other so-called actualités are directed--events have been manipulated. The camera is not an invisible recorder; it influences. "L'Arrivée d'un train" and some other actuality films do appear to be undirected, though; some even achieve the metaphoric invisibility of the camera (Louis Le Prince's "Traffic Crossing Leeds Bridge" (1888) appears to accomplish it).

Reportedly (including by Méliès), when this film was projected to audiences, the projectionist would temporarily freeze the first frame and then amaze audiences by running the motion picture. Méliès later said of this: "I must admit we were all stupefied as you can understand. I immediately said, 'That's for me. What an extraordinary thing.'"

On an interesting side note, the first projectionist of these showings was Charles Moisson, who also introduced the Lumière's to film, helped them invent the Cinématographe and made some of the company's earlier films. With Francis Doublier (who claims to appear in "Leaving the Lumière Factory"), they photographed the coronation of Tsar Nikolas II, which ended in tragedy when a stand gave way and thousands of people were trampled to death in an ensuing panic. Russian authorities confiscated the film, and it was never seen again. On the issue of actuality films, this was a dramatic example of the camera as a relative non-participant of events.

Anyhow, this film, "Leaving the Lumière Factory", is an important landmark in film history, for not only introducing many to cinema, but also for introducing, through their actuality films, a new way of seeing. Within and without the frame, the gates were opened.

(Note: This is the fifth in a series of my comments on 10 "firsts" in film history. The other films covered are Traffic Crossing Leeds Bridge (1888), Blacksmith Scene (1893), Annabelle Serpentine Dance (1895), The Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots (1895), L'Arroseur arose (1895), L'Arrivée d'un train à La Ciotat (1896), Panorama du Grand Canal vu d'un bateau (1896), Return of Lifeboat (1897) and Panorama of Eiffel Tower (1900).)

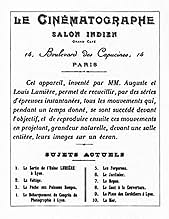

Story says that on that on December 28, 1895, a small group of thirty-three people was gathered at Paris's Salon Indien Du Grand Café to witness the Cinématographe, a supposedly new invention that resulted from the work done by a couple of photographers named August and Louis Lumière. The small audience reunited that day (some by invitation, most due to curiosity) didn't really know what to expect from the show, and when a stationary photograph appeared projected on a screen, most thought that the Cinématographe was just another fancy devise to present slide-show projections. Until the photograph started to move. What those thirty-three people experienced in awe that cold day of December was the very first public screening of a moving picture being projected on a screen; history was being written and cinema as we know it was born that day.

Of the 10 short movies that were shown during that historic day, "La Sortie Des Usines Lumière" (literally "Exiting the Lumière Factory") was the very first to be screened. The film shows the many workers of the Lumière factory as they walk through the gates of the factory, leaving the building at the end of a hard day of work. While a very basic "actuality film" (movie depicting a real event), the movie took everyone in the audience by surprise, as their concept of moving pictures was limited to Edison's "Peep Show" machines (the Kinetoscope), the brothers' invention was like nothing they had seen before and so the audience stood in awe, as the people and the horses moved across the screen. The idea wasn't entirely new (Le Prince shot the first movie as early as 1888), but the way of showing the movie was simply revolutionary.

"La Sortie Des Usines Lumière" would become the first in the long series of "actuality films" that the Lumière would produce over the years. This primitive form of documentary was the brothers' favorite kind of film because they were more interested in the technological aspects of their invention than in the uses the Cinématographe could have. Despite the initial lack of enthusiasm, after the first showing the Cinématographe became a great success and "La Sortie Des Usines Lumière" quickly became an iconic image of that first screening. It definitely wasn't the first movie the brothers shot that year, and it probably wasn't the best of the 10 movies shown that day (personally I think that "L' Arroseur Arrosé" was the best of the 10); however, it is really meaningful that the very first movie was the opening of a pair of gates, as literally, this movie opened the gates to cinema as we know it. 8/10

Of the 10 short movies that were shown during that historic day, "La Sortie Des Usines Lumière" (literally "Exiting the Lumière Factory") was the very first to be screened. The film shows the many workers of the Lumière factory as they walk through the gates of the factory, leaving the building at the end of a hard day of work. While a very basic "actuality film" (movie depicting a real event), the movie took everyone in the audience by surprise, as their concept of moving pictures was limited to Edison's "Peep Show" machines (the Kinetoscope), the brothers' invention was like nothing they had seen before and so the audience stood in awe, as the people and the horses moved across the screen. The idea wasn't entirely new (Le Prince shot the first movie as early as 1888), but the way of showing the movie was simply revolutionary.

"La Sortie Des Usines Lumière" would become the first in the long series of "actuality films" that the Lumière would produce over the years. This primitive form of documentary was the brothers' favorite kind of film because they were more interested in the technological aspects of their invention than in the uses the Cinématographe could have. Despite the initial lack of enthusiasm, after the first showing the Cinématographe became a great success and "La Sortie Des Usines Lumière" quickly became an iconic image of that first screening. It definitely wasn't the first movie the brothers shot that year, and it probably wasn't the best of the 10 movies shown that day (personally I think that "L' Arroseur Arrosé" was the best of the 10); however, it is really meaningful that the very first movie was the opening of a pair of gates, as literally, this movie opened the gates to cinema as we know it. 8/10

This one-minute film is arguably the first movie ever made. Other inventors had previously filmed actions - like Edison's motion photography of a sneeze - but the Lumiere brothers developed equipment that tremendously advanced the medium. At the time, of course, their `cinematograph' must have bewildered their peers, including their subjects. In this first instance, the brothers record employees leaving their factory, some of whom understandably struggle to hide their awareness of the camera. The Lumieres attempt to make the film more entertaining by introducing animals and a bicycle, but `La Sortie Des Usines Lumiere' doesn't nearly match the ingenuity of their later films. The most interesting aspect of this short film is the brothers' selection of a familiar working class ritual as their subject. Their choice is the initial evidence of their curiosity about all of the world's people, a quality that makes viewing their experiments immensely rewarding and fascinating today.

Rating: 8

Rating: 8

क्या आपको पता है

- ट्रिवियाIt was the first film ever to be projected to a paying audience.

- इसके अलावा अन्य वर्जनThree versions of the film exist. There are a number of differences between them, such as the clothing styles worn by the workers change to reflect the different seasons the versions were shot in, and the horse-drawn carriage that appears in the first version is pulled by one horse, two horses in the second version, and no horse and no carriage in the third version.

- कनेक्शनEdited into The Lumière Brothers' First Films (1996)

टॉप पसंद

रेटिंग देने के लिए साइन-इन करें और वैयक्तिकृत सुझावों के लिए वॉचलिस्ट करें

विवरण

- रिलीज़ की तारीख़

- कंट्री ऑफ़ ओरिजिन

- आधिकारिक साइटें

- भाषा

- इस रूप में भी जाना जाता है

- Employees Leaving the Lumière Factory

- फ़िल्माने की जगहें

- उत्पादन कंपनी

- IMDbPro पर और कंपनी क्रेडिट देखें

- चलने की अवधि1 मिनट

- रंग

- ध्वनि मिश्रण

- पक्ष अनुपात

- 1.33 : 1

इस पेज में योगदान दें

किसी बदलाव का सुझाव दें या अनुपलब्ध कॉन्टेंट जोड़ें

टॉप गैप

By what name was La sortie de l'usine Lumière à Lyon (1895) officially released in India in English?

जवाब