NOTE IMDb

7,6/10

8,7 k

MA NOTE

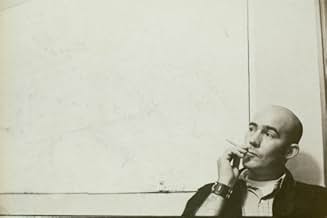

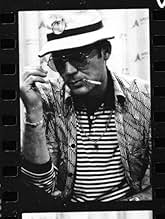

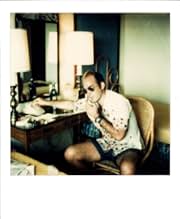

Ajouter une intrigue dans votre langueA portrait of the late gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson.A portrait of the late gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson.A portrait of the late gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson.

- Réalisation

- Scénario

- Casting principal

- Récompenses

- 1 victoire et 5 nominations au total

Hunter S. Thompson

- Self

- (images d'archives)

Oscar Acosta

- Self

- (images d'archives)

Muhammad Ali

- Self

- (images d'archives)

Warren Beatty

- Self

- (images d'archives)

Avis à la une

Hunter S. Thompson was a supremely funny man but, alas, was a deeply unhappy one. Thompson's political positions could have hardly been more different from my own. Nevertheless, I admired his work because he was such an original and so entertaining. I did so mainly because I knew better than to ever take him seriously. Unfortunately, Thompson never learned to not take himself too seriously and that failing led to his self destructiveness and, ultimately to his suicide.

Gonzo: The Life and Work of Dr. Hunter S. Thompson is a mostly loving look at Thompson through the eyes of many of his friends and the politicians he wrote about. It shows a man with a profoundly dichotomous nature: creativeness and wit on its positive side but dark, self destructive depression on the other. It created the richly entertaining Gonzo journalist who those of us who admired his work so enjoyed but also planted the seeds for his depression and death.

Near the end of the film, Thompson's first wife, Sondi, takes issue with those who characterize Thompson's suicide as "heroic." I think she has a point. Thompson had largely fallen from the public eye some years before he killed himself in 2005 at the age of 67. In a note delivered to his wife four days before his death, which was described by both his family and the police as a suicide note, Thompson wrote, under the title "Football Season is Over":

"No More Games. No More Bombs. No More Walking. No More Fun. No More Swimming. 67. That is 17 years past 50. 17 more than I needed or wanted. Boring. I am always bitchy. No Fun — for anybody. 67. You are getting Greedy. Act your old age. Relax — This won't hurt."

That about sums it up.

Gonzo: The Life and Work of Dr. Hunter S. Thompson is a mostly loving look at Thompson through the eyes of many of his friends and the politicians he wrote about. It shows a man with a profoundly dichotomous nature: creativeness and wit on its positive side but dark, self destructive depression on the other. It created the richly entertaining Gonzo journalist who those of us who admired his work so enjoyed but also planted the seeds for his depression and death.

Near the end of the film, Thompson's first wife, Sondi, takes issue with those who characterize Thompson's suicide as "heroic." I think she has a point. Thompson had largely fallen from the public eye some years before he killed himself in 2005 at the age of 67. In a note delivered to his wife four days before his death, which was described by both his family and the police as a suicide note, Thompson wrote, under the title "Football Season is Over":

"No More Games. No More Bombs. No More Walking. No More Fun. No More Swimming. 67. That is 17 years past 50. 17 more than I needed or wanted. Boring. I am always bitchy. No Fun — for anybody. 67. You are getting Greedy. Act your old age. Relax — This won't hurt."

That about sums it up.

Before watching this film I knew a decent amount about the father of Gonzo journalism, and everything I had learned seemed to suggest a man whose many contradictions made his overall nature hard to grasp. For this reason I praise this film for doing a remarkable job of really digging into the essence of all that is Hunter S. Thompson, including his writing, his lifestyle, his acquaintances, and primarily his impact upon America.

Gonzo: The Life and Work of Dr. Hunter S.Thompson methodically covers the bulk of Hunter's life from his boyhood to his untimely suicide. With interviews from many of his close friends and relatives, as well as some substantial political figures, the movie does a great job of putting his life in perspective. Consequently, it brings with it the energy and intensity that was pervasive in those times and places, like San Francisco in the early 60s. But Hunter's life is far more than sheer counterculture excitement, and the film covers the many events of civil disarray that Thompson fell witness to, and that shaped his cynical view of modern-day America.

The film manages to draw many parallels to the afflictions of our nation today, such as the war in Iraq and Bush administration. It follows Hunter's life all the way to the end, and in spite of the last quarter of the movie being a bit too lengthy, closes decently. For its effectiveness and emotional force, this is a must-see for Gonzo fans.

Gonzo: The Life and Work of Dr. Hunter S.Thompson methodically covers the bulk of Hunter's life from his boyhood to his untimely suicide. With interviews from many of his close friends and relatives, as well as some substantial political figures, the movie does a great job of putting his life in perspective. Consequently, it brings with it the energy and intensity that was pervasive in those times and places, like San Francisco in the early 60s. But Hunter's life is far more than sheer counterculture excitement, and the film covers the many events of civil disarray that Thompson fell witness to, and that shaped his cynical view of modern-day America.

The film manages to draw many parallels to the afflictions of our nation today, such as the war in Iraq and Bush administration. It follows Hunter's life all the way to the end, and in spite of the last quarter of the movie being a bit too lengthy, closes decently. For its effectiveness and emotional force, this is a must-see for Gonzo fans.

Hunter S. Thompson was an often astute commentator of American life, and an always astute commentator of his own mental disintegration, a process driven by his own enthusiastic use of mind-altering drugs; a gun freak who opposed American involvement in Vietnam; and a critic of capitalism who became, pretty much, the living embodiment of his own brand. He also, years after his best work was done, died by shooting himself. This documentary provides insight into his strange journey, which does have a tragic dimension: the values of the life he lived, the adulation he received for living it and the damage it did to him appear in the end inseparable. By the end, he was still celebrated (by new generations of kids who love to get high) but no longer relevant, his final act a desperate (and arguably failed) plea for attention. This documentary tells us much of the story, mostly interestingly, though there are times when it fails to disentangle the process it describes, the overwhelming of man by self-created myth. Still, while it's the prerogative of every generation to feel jaded, I find it hard to imagine another figure like Hunter emerging today, if only because a large part of his quality was that no-one expected him. But the film reminds you of another part as well: he could certainly write.

Gonzo: The Life and Work of Dr. Hunter S. Thompson: 6 out of 10: Is Hunter S Thompson any more relevant to modern journalism than Joe Namath is to modern football? After all, both were men of their times. In addition, both faded badly by the mid-seventies. Thompson's early work is excellent (a copy of "The Proud Highway" sits on my bookshelf) and reached its pinnacle with Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail '72.

A mere three years later Rolling Stone publisher Jenn Warner had become so fed up with Thompson he basically tried to have him killed.

As Gonzo.org puts it "Then, early one evening in March 1975, Hunter was watching a nightmarish film of the evacuation of Da Nang on the evening news. The phone rang, and Hunter picked it up. It was Wenner, saying, "How would you like to go to Vietnam?" Hunter could not resist. The collapse of the American empire was a happening tailor-made for his talents. Within days, he was heading out over the Pacific. He arrived in Saigon hours after Thieu's palace had been bombed and staffed by his own Air Force. For a man who lived with the conviction that the world was going to end next Monday, this was an especially ominous portent. Thompson had the sense of "walking into a death camp." This was it. He would never get out alive. As it turned out, the fate that was in store for him was even worse. Thompson discovered that, even as he was on his way to Vietnam, Wenner had taken him off retainer - in effect, fired him - and with the retainer went his staff benefits, including health and life insurance." Also leaving him no way out of Vietnam... a one-way ticket if you will.

Dude that is cold...

And that is the very nature of the problem with this documentary. Why is not this story mentioned? Who knows? It certainly was a turning point in Thompsons life (He apparently became more withdrawn and paranoid afterwards... understandably so) Gonzo is a pollyanna look at Thompson. The abuse of his first marriage gets a glancing look and all the interviewees (Including Jimmy Carter, Pat Buchanan and Jenn Werner) seem hesitant to speak ill of the dead.

The fact that in a few short years Thompson turned from a well-respected writer into a Muppet and Doonesbury cartoon is not covered well. The fact is mentioned but the reasons are glossed over. It is as if the film is worried that by mentioning his failures it will reduce his significance.

Yet, I would argue that Thompson's effect on Journalism is larger than he gets credit for. Reporters nowadays often ignore facts, concentrating instead on how events make them feel. Anderson Cooper crying during the Hurricane Katrina coverage threatened to become a bigger story than the storm itself. (He was not helped when fellow Mensa candidate Wolf Blitzer said "You simply get chills every time you see these poor individuals…many of these people, almost all of them that we see are so poor and they are so black") The documentary never really focuses on this aspect either. Gonzo seems to fear pulling back any of the masks its subject wears presumably scared of what it might find. Gonzo would have been better served concentrating on one period of time and focusing its energies.

That said, for those unfamiliar with Hunter S Thompson outside of his Muppet form this is a good start. Moreover, if it gets people to read his early work so much the better.

A mere three years later Rolling Stone publisher Jenn Warner had become so fed up with Thompson he basically tried to have him killed.

As Gonzo.org puts it "Then, early one evening in March 1975, Hunter was watching a nightmarish film of the evacuation of Da Nang on the evening news. The phone rang, and Hunter picked it up. It was Wenner, saying, "How would you like to go to Vietnam?" Hunter could not resist. The collapse of the American empire was a happening tailor-made for his talents. Within days, he was heading out over the Pacific. He arrived in Saigon hours after Thieu's palace had been bombed and staffed by his own Air Force. For a man who lived with the conviction that the world was going to end next Monday, this was an especially ominous portent. Thompson had the sense of "walking into a death camp." This was it. He would never get out alive. As it turned out, the fate that was in store for him was even worse. Thompson discovered that, even as he was on his way to Vietnam, Wenner had taken him off retainer - in effect, fired him - and with the retainer went his staff benefits, including health and life insurance." Also leaving him no way out of Vietnam... a one-way ticket if you will.

Dude that is cold...

And that is the very nature of the problem with this documentary. Why is not this story mentioned? Who knows? It certainly was a turning point in Thompsons life (He apparently became more withdrawn and paranoid afterwards... understandably so) Gonzo is a pollyanna look at Thompson. The abuse of his first marriage gets a glancing look and all the interviewees (Including Jimmy Carter, Pat Buchanan and Jenn Werner) seem hesitant to speak ill of the dead.

The fact that in a few short years Thompson turned from a well-respected writer into a Muppet and Doonesbury cartoon is not covered well. The fact is mentioned but the reasons are glossed over. It is as if the film is worried that by mentioning his failures it will reduce his significance.

Yet, I would argue that Thompson's effect on Journalism is larger than he gets credit for. Reporters nowadays often ignore facts, concentrating instead on how events make them feel. Anderson Cooper crying during the Hurricane Katrina coverage threatened to become a bigger story than the storm itself. (He was not helped when fellow Mensa candidate Wolf Blitzer said "You simply get chills every time you see these poor individuals…many of these people, almost all of them that we see are so poor and they are so black") The documentary never really focuses on this aspect either. Gonzo seems to fear pulling back any of the masks its subject wears presumably scared of what it might find. Gonzo would have been better served concentrating on one period of time and focusing its energies.

That said, for those unfamiliar with Hunter S Thompson outside of his Muppet form this is a good start. Moreover, if it gets people to read his early work so much the better.

After Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room, Taxi to the Dark Side, and this vivid, significant depiction of the Sixties and Seventies superstar journalist Hunter Thompson, Alex Gibney has emerged as clearly one of the best documentary filmmakers we've got and also one of the most prolific.

Gibney tells a very smart, very verbal, very funny but also intensely significant story here. Some of the people who speak most highly of Thompson on camera are Billy Carter, William McGovern, and longtime Republican presidential adviser Pat Buchanan,as well as writer Tom Woolf and Thompson's editors at Rolling Stone, for which he did his best periodical pieces, the notable ones turned into books. More intimate details--but the man was such a perpetual performer that public and private are hard to separate--come from Thompson's first and second wives. And the English artist Ralph Steadman, who illustrated the writing, has much to say, as do plenty of others. When Steadman first met Thompson he fed the Brit Psilocybin and he was never the same. Steadman became an invaluable cohort and collaborator and his wild drawings provide a perfect visual counterpart to Thompson's written words on screen.

Thompson was a notorious wild man from early on. "I wouldn't recommend sex, drugs or insanity for everyone, but they've always worked for me," he said. Prodigious in his consumption of drugs and alcohol, he was witness to some of the great events of his time, and got deeply involved in politics and opposition to the Vietnam war and of course the counterculture. Lean, athletic, flashily dressed, with trademark balding pate, big sunglasses, cigarette holder and drink in hand, Thompson was a demon at the IBM Selectric, gleefully spinning out brilliant pieces nobody else could have written, a master of outrage and wit.

Fueled by craziness, substances, and his own tongue-in-cheek joie de vivre, he devised his own outrageous style of writing in which cold clear fact was blended with wild invention and the adjectives and metaphors flew like hornets around a honey pot. Others too partook of the kind of journalism he practiced. The times--the flamboyant and boisterous and revolutionary Sixties and early Seventies-- seemed to call for a new more violent, more committed language in journalism. Norman Mailer also wrote about the democratic convention in Chicago in 1968 and on hand for Esquire were the likes of Jean Genet and William Burroughs. Three is something of Burroughs in Thompson, the drugs and the outrage and a way of seeing convention as conspiracy. One of Thompson's famous quotes gives a hint of the link: "America... just a nation of two hundred million used car salesmen with all the money we need to buy guns and no qualms about killing anybody else in the world who tries to make us uncomfortable." This was the moment when the distinction between fiction and non-fiction blurred: Tom Wolfe (The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, which used raw material from the more adventurous Thompson), Thompson's act of "embedded journalism" as Wolfe calls it, Hell's Angels), Truman Capote's murder story In Cold Blood done for The New Yorker, were all variations on the idea of the "non-fiction novel." Mailer had done a heroically personal and novelistic account of the 1967 March on the Pentagon, The Armies of the Night. The film might do a bit more to put Thompson in all this context, but it's clearly implied. He called his wild style "gonzo" journalism.

Thompson also wrote about Las Vegas as the American dream and about Nixon, whom he loathed. He also used a tape recorder a lot. This provides great material for the film. So does the Terry Gilliam film version of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas; and Johnny Depp, who played Thompson in the film and became a great fan and friend, reads salient passages sitting in front of a well-stocked bar. Depp paid for the spectacular monument/funeral for the writer that Thompson had--on film--planned out long before, in which his ashes are fired into the Colorado hills. Ralph Steadman did the sketches. This is shown at the end of the film and provides a lovely son et lumière finale.

Thompson's innate violence may explain how he could have blended in so well for a while with the Hell's Angels. He kept at least twenty firearms on hand in his house, all loaded, his first wife reports. He always planned to end his life with suicide and he shot himself. He did it on a nice day in February almost as a family event, with his son, daughter-in-law and grandson at the house and on the phone with his wife, a shot to the head, at the age of 68, not an act of depression but the completion of a careful plan. It was over. And he had been here to see George W. Bush and predict the decline and fall of the American empire. A late collection of short pieces is entitled Hey Rube: Blood Sport, the Bush Doctrine, and the Downward Spiral of Dumbness.

His dissipation took its toll and so did fame. He fell into playing a self-parodying avatar of himself and his writing deteriorated after the later Seventies, so he had about ten good years and about twenty not-so-good ones. Some have dwelt on his decline; Gonzo doesn't. His writing faltered as early as 1974 when he went to Zaire with Steadman to cover the Foreman-Ali "Rumble in the Jungle" and he got drunk at the pool during the fight and never finished the story. Given how bright he burned and how hard he lived, it was inevitable that the man would burn out early And writing did not by any means fizzle out even into the Nineties. There is an immense wealth of spinoffs on film; Gibney had rich, rich material to work with here.

The best that could happen is that this beautifully edited and greatly entertaining film makes a host of new converts to the writing.

Gibney tells a very smart, very verbal, very funny but also intensely significant story here. Some of the people who speak most highly of Thompson on camera are Billy Carter, William McGovern, and longtime Republican presidential adviser Pat Buchanan,as well as writer Tom Woolf and Thompson's editors at Rolling Stone, for which he did his best periodical pieces, the notable ones turned into books. More intimate details--but the man was such a perpetual performer that public and private are hard to separate--come from Thompson's first and second wives. And the English artist Ralph Steadman, who illustrated the writing, has much to say, as do plenty of others. When Steadman first met Thompson he fed the Brit Psilocybin and he was never the same. Steadman became an invaluable cohort and collaborator and his wild drawings provide a perfect visual counterpart to Thompson's written words on screen.

Thompson was a notorious wild man from early on. "I wouldn't recommend sex, drugs or insanity for everyone, but they've always worked for me," he said. Prodigious in his consumption of drugs and alcohol, he was witness to some of the great events of his time, and got deeply involved in politics and opposition to the Vietnam war and of course the counterculture. Lean, athletic, flashily dressed, with trademark balding pate, big sunglasses, cigarette holder and drink in hand, Thompson was a demon at the IBM Selectric, gleefully spinning out brilliant pieces nobody else could have written, a master of outrage and wit.

Fueled by craziness, substances, and his own tongue-in-cheek joie de vivre, he devised his own outrageous style of writing in which cold clear fact was blended with wild invention and the adjectives and metaphors flew like hornets around a honey pot. Others too partook of the kind of journalism he practiced. The times--the flamboyant and boisterous and revolutionary Sixties and early Seventies-- seemed to call for a new more violent, more committed language in journalism. Norman Mailer also wrote about the democratic convention in Chicago in 1968 and on hand for Esquire were the likes of Jean Genet and William Burroughs. Three is something of Burroughs in Thompson, the drugs and the outrage and a way of seeing convention as conspiracy. One of Thompson's famous quotes gives a hint of the link: "America... just a nation of two hundred million used car salesmen with all the money we need to buy guns and no qualms about killing anybody else in the world who tries to make us uncomfortable." This was the moment when the distinction between fiction and non-fiction blurred: Tom Wolfe (The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, which used raw material from the more adventurous Thompson), Thompson's act of "embedded journalism" as Wolfe calls it, Hell's Angels), Truman Capote's murder story In Cold Blood done for The New Yorker, were all variations on the idea of the "non-fiction novel." Mailer had done a heroically personal and novelistic account of the 1967 March on the Pentagon, The Armies of the Night. The film might do a bit more to put Thompson in all this context, but it's clearly implied. He called his wild style "gonzo" journalism.

Thompson also wrote about Las Vegas as the American dream and about Nixon, whom he loathed. He also used a tape recorder a lot. This provides great material for the film. So does the Terry Gilliam film version of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas; and Johnny Depp, who played Thompson in the film and became a great fan and friend, reads salient passages sitting in front of a well-stocked bar. Depp paid for the spectacular monument/funeral for the writer that Thompson had--on film--planned out long before, in which his ashes are fired into the Colorado hills. Ralph Steadman did the sketches. This is shown at the end of the film and provides a lovely son et lumière finale.

Thompson's innate violence may explain how he could have blended in so well for a while with the Hell's Angels. He kept at least twenty firearms on hand in his house, all loaded, his first wife reports. He always planned to end his life with suicide and he shot himself. He did it on a nice day in February almost as a family event, with his son, daughter-in-law and grandson at the house and on the phone with his wife, a shot to the head, at the age of 68, not an act of depression but the completion of a careful plan. It was over. And he had been here to see George W. Bush and predict the decline and fall of the American empire. A late collection of short pieces is entitled Hey Rube: Blood Sport, the Bush Doctrine, and the Downward Spiral of Dumbness.

His dissipation took its toll and so did fame. He fell into playing a self-parodying avatar of himself and his writing deteriorated after the later Seventies, so he had about ten good years and about twenty not-so-good ones. Some have dwelt on his decline; Gonzo doesn't. His writing faltered as early as 1974 when he went to Zaire with Steadman to cover the Foreman-Ali "Rumble in the Jungle" and he got drunk at the pool during the fight and never finished the story. Given how bright he burned and how hard he lived, it was inevitable that the man would burn out early And writing did not by any means fizzle out even into the Nineties. There is an immense wealth of spinoffs on film; Gibney had rich, rich material to work with here.

The best that could happen is that this beautifully edited and greatly entertaining film makes a host of new converts to the writing.

Le saviez-vous

- AnecdotesAt 1:35 you can see a Richard Nixon mask under the TV. This is a nod to the 1980 movie "Where The Buffalo Roam" starring Bill Murray as Thompson, where he uses that mask to train his dog to attack a scarecrow-like recreation of the former President.

- GaffesWhen the film mentions that Hunter Thompson had a crush on Jefferson Airplane singer Grace Slick, archival footage instead shows the Airplane's first female singer, Signe Anderson.

- ConnexionsFeatures To Tell the Truth (1956)

Meilleurs choix

Connectez-vous pour évaluer et suivre la liste de favoris afin de recevoir des recommandations personnalisées

- How long is Gonzo?Alimenté par Alexa

Détails

Box-office

- Montant brut aux États-Unis et au Canada

- 1 252 100 $US

- Week-end de sortie aux États-Unis et au Canada

- 191 942 $US

- 6 juil. 2008

- Montant brut mondial

- 1 491 958 $US

- Durée

- 2h(120 min)

- Couleur

- Mixage

- Rapport de forme

- 1.85 : 1

Contribuer à cette page

Suggérer une modification ou ajouter du contenu manquant