NOTE IMDb

6,8/10

5,3 k

MA NOTE

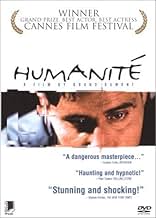

Un détective de police qui a oublié comment ressentir des émotions - à cause de la mort de sa propre famille dans une sorte d'accident - enquête sur un crime mystérieux, qui s'avère poser pl... Tout lireUn détective de police qui a oublié comment ressentir des émotions - à cause de la mort de sa propre famille dans une sorte d'accident - enquête sur un crime mystérieux, qui s'avère poser plus de questions qu'il n'apporte de réponses.Un détective de police qui a oublié comment ressentir des émotions - à cause de la mort de sa propre famille dans une sorte d'accident - enquête sur un crime mystérieux, qui s'avère poser plus de questions qu'il n'apporte de réponses.

- Réalisation

- Scénario

- Casting principal

- Récompenses

- 3 victoires et 3 nominations au total

Darius

- L'infirmier

- (as Daniel Leroux)

Robert Bunzi

- Le policier anglais

- (as Robert Bunzl)

Avis à la une

This French oddity from second-time director Bruno Dumont is a masterpiece. Four minutes into the film I was ready to switch it off, but once I'd settled into the rhythm of the film I was transfixed. That took about 20 minutes, and once I'd finished the film I re-watched those first 20 minutes again.

A policeman investigates the brutal murder of a young girl in a French town and that's pretty much it. It's even less than that in some respects. For example the girl is found in the opening minutes, but it's 50 minutes before any real investigation begins. Instead it focuses on the policeman (Pharaon) and his two friends (lovers Domino and Joseph). They go to the beach, to a restaurant, stand outside their houses having stunted conversations and generally wasting the day away. Pharaon goes for a bicycle ride and tends to his allotment. Essentially nothing happens. There are maybe four or five actual plot points altogether, and the rest is filled with chat of the "Hi, how are you?" variety, long shots of people walking or driving, or opening doors. The entire film follows a kind of rhythmic cycle that becomes hypnotic if you allow it.

Which brings us to the actors. The DVD notes say they're all non-professionals. Not amateur actors, but real people who are acting for the first time. The actor who plays Joseph does reasonably well, but Domino is excellent (and it's an extremely brave performance for any actress).

Emmanuel Schotte (as Pharaon) is amazing. It's simply one of the greatest performances I've ever seen. Imagine Travis Bickle with 99pc of the anger taken out. Then cross him with Forrest Gump (with non of Hanks' caricature or comedy). Cast a non-actor who looks like a cross between Clive Owen and Alfred Molina and you're somewhere close. He's a very unlikely cop. He's wide-eyed, innocent, and simple. He's slow and deliberate. Brief comments from other characters tell us his wife and child died two years ago, and he looks like a man still stunned, as if he'd just heard the news. This is never hinted at once; we don't ever see what he was like before, no one ever tells him "You've changed", but the audience gets the feeling this is a man suffering desperately from the pain of grief. Most of this is expressed in Schotte's eyes which are desperately sad.

This low-key little film requires patience. Without Schotte's performance I don't think there'd be much of a film here. Be prepared for an extremely slow film, but one that's never boring. It will polarise opinion like few other films I've seen so I can't recommend it to everyone (and there are some very graphic sex scenes), but I thought it was amazing.

A policeman investigates the brutal murder of a young girl in a French town and that's pretty much it. It's even less than that in some respects. For example the girl is found in the opening minutes, but it's 50 minutes before any real investigation begins. Instead it focuses on the policeman (Pharaon) and his two friends (lovers Domino and Joseph). They go to the beach, to a restaurant, stand outside their houses having stunted conversations and generally wasting the day away. Pharaon goes for a bicycle ride and tends to his allotment. Essentially nothing happens. There are maybe four or five actual plot points altogether, and the rest is filled with chat of the "Hi, how are you?" variety, long shots of people walking or driving, or opening doors. The entire film follows a kind of rhythmic cycle that becomes hypnotic if you allow it.

Which brings us to the actors. The DVD notes say they're all non-professionals. Not amateur actors, but real people who are acting for the first time. The actor who plays Joseph does reasonably well, but Domino is excellent (and it's an extremely brave performance for any actress).

Emmanuel Schotte (as Pharaon) is amazing. It's simply one of the greatest performances I've ever seen. Imagine Travis Bickle with 99pc of the anger taken out. Then cross him with Forrest Gump (with non of Hanks' caricature or comedy). Cast a non-actor who looks like a cross between Clive Owen and Alfred Molina and you're somewhere close. He's a very unlikely cop. He's wide-eyed, innocent, and simple. He's slow and deliberate. Brief comments from other characters tell us his wife and child died two years ago, and he looks like a man still stunned, as if he'd just heard the news. This is never hinted at once; we don't ever see what he was like before, no one ever tells him "You've changed", but the audience gets the feeling this is a man suffering desperately from the pain of grief. Most of this is expressed in Schotte's eyes which are desperately sad.

This low-key little film requires patience. Without Schotte's performance I don't think there'd be much of a film here. Be prepared for an extremely slow film, but one that's never boring. It will polarise opinion like few other films I've seen so I can't recommend it to everyone (and there are some very graphic sex scenes), but I thought it was amazing.

The French writer-director Bruno Dumont achieves something rarely accomplished since TAXI DRIVER and ERASERHEAD: a way of looking at the world entirely afresh. Unlike those movies--or the recent, Expressionist CLEAN, SHAVEN--Dumont doesn't distort the physical world, make it elastic or dreamlike. But he somehow makes us feel the world is being recorded by a very wise child from another planet. Everything, absolutely everything, from human behavior to wind rippling over a field of grass, is seen as never before. Ezra Pound's injunction to "make it new" is stamped on every frame.

Pharaon is a slow-witted police superintendent who is anything but pharaonic. He had a girlfriend and a baby, now dead. (We are not told how.) He is friends with Domino, a big-boned, sensitive, slatternly woman next door, and Joseph, her handsome beau, with whom she seems to never stop having sex. In their small town, a little girl has been raped and murdered. Pharaon pursues this case, as he pursues a sort of inarticulate love for Domino. Along the way, a light dawns in Pharaon--a dreadful light. He becomes sensitive to the suffering of all living things--a pig hurt by the suckling of her young, all the way to a motorist getting a beating outside police headquarters. The effect this has is to create a kind of moral schizophrenia in Pharaon: he can filter out nothing. Like an overlap of Raskolnikov and Prince Mishkin, Pharaon takes both the world's sin and sufferings on his back.

But this gives only the barest outline of the experience of L'HUMANITE, which is not about its plot. Indeed, the relationship of Dumont's handling of the materials of cinema to the story itself is unique in my experience of narrative moviemaking. Like Abbas Kiarostami in his recent work, Dumont uses the landscape not to illustrate the story, but to propose a dialectic against it. Where the landscape acts as an argument for life in Kiarostami's TASTE OF CHERRY, here it does something else. It vibrates with feeling. In its childlike gaze at the hardness of people and things, L'HUMANITE tries to get at the shifting feelings underneath--the emotions and sensations so elusive there are no words for them. The movie proves that literary means--finding names--are unnecessary. Dumont finds aural-visual-rhythmic means to voice those emotions.

His techniques can be daring, appalling. Pharaon, gradually overwhelmed by the world's thousand and one cruelties, starts to spontaneously embrace (relative) total strangers, in scenes one can imagine giving audiences giggles. Dumont doesn't care.

L'HUMANITE is the kind of movie that, while you're watching it, you feel can drive you crazy in places, but which you know you'll live with and re-play in your head for the rest of your life. And Cannes naysayers to the contrary, all the performances in this movie--all of them, down to the tiniest--are perfect.

A note: I would like to thank the other people who wrote about L'HUMANITE on IMDB. With no other movie have I felt I learned so much by reading other people's responses, and particularly noting the details they chose to underline. For the authenticity and unabashedness of everyone's responses, I am truly grateful.

Pharaon is a slow-witted police superintendent who is anything but pharaonic. He had a girlfriend and a baby, now dead. (We are not told how.) He is friends with Domino, a big-boned, sensitive, slatternly woman next door, and Joseph, her handsome beau, with whom she seems to never stop having sex. In their small town, a little girl has been raped and murdered. Pharaon pursues this case, as he pursues a sort of inarticulate love for Domino. Along the way, a light dawns in Pharaon--a dreadful light. He becomes sensitive to the suffering of all living things--a pig hurt by the suckling of her young, all the way to a motorist getting a beating outside police headquarters. The effect this has is to create a kind of moral schizophrenia in Pharaon: he can filter out nothing. Like an overlap of Raskolnikov and Prince Mishkin, Pharaon takes both the world's sin and sufferings on his back.

But this gives only the barest outline of the experience of L'HUMANITE, which is not about its plot. Indeed, the relationship of Dumont's handling of the materials of cinema to the story itself is unique in my experience of narrative moviemaking. Like Abbas Kiarostami in his recent work, Dumont uses the landscape not to illustrate the story, but to propose a dialectic against it. Where the landscape acts as an argument for life in Kiarostami's TASTE OF CHERRY, here it does something else. It vibrates with feeling. In its childlike gaze at the hardness of people and things, L'HUMANITE tries to get at the shifting feelings underneath--the emotions and sensations so elusive there are no words for them. The movie proves that literary means--finding names--are unnecessary. Dumont finds aural-visual-rhythmic means to voice those emotions.

His techniques can be daring, appalling. Pharaon, gradually overwhelmed by the world's thousand and one cruelties, starts to spontaneously embrace (relative) total strangers, in scenes one can imagine giving audiences giggles. Dumont doesn't care.

L'HUMANITE is the kind of movie that, while you're watching it, you feel can drive you crazy in places, but which you know you'll live with and re-play in your head for the rest of your life. And Cannes naysayers to the contrary, all the performances in this movie--all of them, down to the tiniest--are perfect.

A note: I would like to thank the other people who wrote about L'HUMANITE on IMDB. With no other movie have I felt I learned so much by reading other people's responses, and particularly noting the details they chose to underline. For the authenticity and unabashedness of everyone's responses, I am truly grateful.

"The power of cinema lies in the return of man to the body, to the heart, to truth" - Bruno Dumont

In L'Humanite, by Bruno Dumont (La Vie de Jesus), Pharaon de Winter (Emmanuel Schotte) is a Police Superintendent called upon to investigate the murder and rape of an 11-year old girl. Flaunting almost every cinematic convention, the film is not about solving a crime but a 2 1/2-hour poem of mood, time, silence and spirit. Set in northern France in the director's hometown of Bailleul, the characters are unglamorous members of the working class. Dumont devotes long stretches of the film to simply observing Pharaon going about his life: eating an apple, tending his garden, watching a soccer game on television, interacting with his mother, or being a friend to his neighbor Domino (Severine Caneele), a rugged factory worker and her obnoxious bus-driver boyfriend Joseph (Philippe Tullier). He is an unlikely cop, a passive, stoop-shouldered, and empathetic man who would sooner kiss a prisoner on the lips or stroke his neck as browbeat him. Pharaon sees the suffering of the world and wants to hold it in his hands and stroke it. Schotte's performance is so expressive that his best actor award at Cannes was criticized because most people thought he wasn't acting, just being himself.

As the film opens, a man is walking in the distance alone across a grassy hill. Suddenly as the camera moves in for a close-up, he collapses in the mud and just lays there for a while. Is he dead or alive? Did he commit the crime? In the next scene, he is sitting in his car listening to harpsichord music and we discover that he is a policeman talking in a barely audible voice to his superior. The film cuts away to the battered body of an 11-year old girl, her torn and bloody vagina graphically shown as the police gather. Pharaon maintains the same anguished, enigmatic look on his face throughout that makes us uncertain if he is the murderer or the Second Coming of Christ. We know very little about him except that he "lost" his wife and child a few years ago, but it is never made clear whether he lost them or they lost him. Signs of passion or involvement are rare but come with a sudden ferocity, as when he is walking across the crime scene and starts to scream at the top of his lungs, a sound drowned out only by the passing Eurostar train.

L'Humanite is an involving and disturbing film that you cannot feel lukewarm about. It is profoundly moving but often agonizingly slow and virtually unwatchable in some of its graphic details (you may never want to have sex again after watching these mechanical exercises). The climax of the film is as perplexing as the beginning with an ambiguous resolution that I'm not quite sure what to make of. What I do know is that I felt as vitally alive watching this film as I did the first time that I saw Leolo by Jean-Claude Lauzon. L'Humanite is a breath of fresh air on the turgid cinema landscape and Dumont is as honest and challenging a director as I've seen in quite a long time. His film continually forces us to question what we are looking at and, as the title suggests, keeps bringing us closer and closer to the core of what makes us truly human.

In L'Humanite, by Bruno Dumont (La Vie de Jesus), Pharaon de Winter (Emmanuel Schotte) is a Police Superintendent called upon to investigate the murder and rape of an 11-year old girl. Flaunting almost every cinematic convention, the film is not about solving a crime but a 2 1/2-hour poem of mood, time, silence and spirit. Set in northern France in the director's hometown of Bailleul, the characters are unglamorous members of the working class. Dumont devotes long stretches of the film to simply observing Pharaon going about his life: eating an apple, tending his garden, watching a soccer game on television, interacting with his mother, or being a friend to his neighbor Domino (Severine Caneele), a rugged factory worker and her obnoxious bus-driver boyfriend Joseph (Philippe Tullier). He is an unlikely cop, a passive, stoop-shouldered, and empathetic man who would sooner kiss a prisoner on the lips or stroke his neck as browbeat him. Pharaon sees the suffering of the world and wants to hold it in his hands and stroke it. Schotte's performance is so expressive that his best actor award at Cannes was criticized because most people thought he wasn't acting, just being himself.

As the film opens, a man is walking in the distance alone across a grassy hill. Suddenly as the camera moves in for a close-up, he collapses in the mud and just lays there for a while. Is he dead or alive? Did he commit the crime? In the next scene, he is sitting in his car listening to harpsichord music and we discover that he is a policeman talking in a barely audible voice to his superior. The film cuts away to the battered body of an 11-year old girl, her torn and bloody vagina graphically shown as the police gather. Pharaon maintains the same anguished, enigmatic look on his face throughout that makes us uncertain if he is the murderer or the Second Coming of Christ. We know very little about him except that he "lost" his wife and child a few years ago, but it is never made clear whether he lost them or they lost him. Signs of passion or involvement are rare but come with a sudden ferocity, as when he is walking across the crime scene and starts to scream at the top of his lungs, a sound drowned out only by the passing Eurostar train.

L'Humanite is an involving and disturbing film that you cannot feel lukewarm about. It is profoundly moving but often agonizingly slow and virtually unwatchable in some of its graphic details (you may never want to have sex again after watching these mechanical exercises). The climax of the film is as perplexing as the beginning with an ambiguous resolution that I'm not quite sure what to make of. What I do know is that I felt as vitally alive watching this film as I did the first time that I saw Leolo by Jean-Claude Lauzon. L'Humanite is a breath of fresh air on the turgid cinema landscape and Dumont is as honest and challenging a director as I've seen in quite a long time. His film continually forces us to question what we are looking at and, as the title suggests, keeps bringing us closer and closer to the core of what makes us truly human.

What's this about quiet small towns that so capture the curiosity and imagination of film-makers. Here we have another study by the director of the Life of Jesus (which incidentally is about a small town too)which shows, from the surface, how a Police Superintendant copes with the brutal rape and murder of a young girl. With this as a background, the film proceeds to show the aimlessness in the protanganist's life and his relationships with the people around him.

While the pace of the film is slow, you do get a feeling that such an approach is necessary. As such, you get many long shots. You also get shots that are very upfront and will no doubt make many in the audience feel uneasy.

There will be many different comments about the show. I heard some French guys coming out of the cinema and lauding it as "Pure Cinema" while others have complained that it was pretentious. For me, I thought it was boring.

While the pace of the film is slow, you do get a feeling that such an approach is necessary. As such, you get many long shots. You also get shots that are very upfront and will no doubt make many in the audience feel uneasy.

There will be many different comments about the show. I heard some French guys coming out of the cinema and lauding it as "Pure Cinema" while others have complained that it was pretentious. For me, I thought it was boring.

On the surface, L'Humanite is about a detective, Pharaon, dealing with his hyper sensitive nature to a rape/murder of a young girl he is investigating, but especially for his unrequited love to his neighbor, Domino. Pharoan is like a wounded, or fearful child, dumpy, perpetually slumped over, soft spoken, watery eyed, whereas Domino is considerably working class, modern, damaged, but not nearly as fearful, at least, not as openly sensitive; unlike Pharaon, she doesn't wear her fear like bad suit. But, that is just the surface of the characters and story, the actual definition of these key elements is left up to the viewer. The plot and the characters are fragments. Instead of miring itself in details, long monologues, heavy dialogue in general, or normal cinematic conventions, the film is purposefully left incomplete in many areas. Thus, the viewer is left to speculate how these gaps should be filled, left to ponder the scraps given to them.

For example, we are told Pharaon's girlfriend and child left him, but not why. Is Pharaon's sensitivity a product of his being abandoned by this woman, or was his sensitivity the cause of her leaving? Domino is clearly upset when Pharaon mentions the case of the rape/murder of the young girl, but is her reaction just empathy, or something deeper? For every detail we are given, there are often unresolved questions that are never conveniently answered.

It somewhat reminds me of a Shohei Imamrua film, like Vengeance is Mine or The Eel, in that the story unfolds through rather mundane scenes, but these scenes end up speaking volumes over the course of the film. You could also say it is a bit like Antonioni as well, as the ordinary, often bright, landscape often contributes just as much emotion as the characters. Basically, Brumo Dumont, like Imamura or Antonioni, eschews normal narrative conventions to tell a story. He lets the viewer fill in the gaps, and much of the film will always remain an engaging mystery.

For example, we are told Pharaon's girlfriend and child left him, but not why. Is Pharaon's sensitivity a product of his being abandoned by this woman, or was his sensitivity the cause of her leaving? Domino is clearly upset when Pharaon mentions the case of the rape/murder of the young girl, but is her reaction just empathy, or something deeper? For every detail we are given, there are often unresolved questions that are never conveniently answered.

It somewhat reminds me of a Shohei Imamrua film, like Vengeance is Mine or The Eel, in that the story unfolds through rather mundane scenes, but these scenes end up speaking volumes over the course of the film. You could also say it is a bit like Antonioni as well, as the ordinary, often bright, landscape often contributes just as much emotion as the characters. Basically, Brumo Dumont, like Imamura or Antonioni, eschews normal narrative conventions to tell a story. He lets the viewer fill in the gaps, and much of the film will always remain an engaging mystery.

Le saviez-vous

- AnecdotesThe body of the raped little girl was a silicone cast.

- Citations

[first lines]

l'inspecteur de police Pharaon De Winter: I'm coming.

- Versions alternativesItalian distributor BIM originally removed about 2 minutes of sex footage from the Italian theatrical release in order to avoid a 'not under 18' rating. When the press criticized this self-censorship attempt, the distributor reissued the film in its original, integral form.

- Bandes originalesLe Vertigo, Rondeau. Modérément

from "Pièce de Clavecin"

Music by Pancrace Royer

Performed by William Christie

Courtesy of harmonia mundi

Meilleurs choix

Connectez-vous pour évaluer et suivre la liste de favoris afin de recevoir des recommandations personnalisées

- How long is Humanité?Alimenté par Alexa

Détails

- Date de sortie

- Pays d’origine

- Sites officiels

- Langues

- Aussi connu sous le nom de

- Humanity

- Lieux de tournage

- Bailleul, Nord, France(Village)

- Sociétés de production

- Voir plus de crédits d'entreprise sur IMDbPro

Box-office

- Montant brut aux États-Unis et au Canada

- 113 495 $US

- Week-end de sortie aux États-Unis et au Canada

- 10 075 $US

- 18 juin 2000

- Durée

- 2h 21min(141 min)

- Couleur

- Mixage

- Rapport de forme

- 2.35 : 1

Contribuer à cette page

Suggérer une modification ou ajouter du contenu manquant