Un journaliste frustré et en quête de liberté usurpe l'identité d'un homme mort, qui s'avère être un trafiquant d'armes.Un journaliste frustré et en quête de liberté usurpe l'identité d'un homme mort, qui s'avère être un trafiquant d'armes.Un journaliste frustré et en quête de liberté usurpe l'identité d'un homme mort, qui s'avère être un trafiquant d'armes.

- Réalisation

- Scénario

- Casting principal

- Récompenses

- 5 victoires et 2 nominations au total

- Robertson

- (as Chuck Mulvehill)

- Hotel Clerk

- (non crédité)

- Murderer's accomplice

- (non crédité)

- Cameraman

- (non crédité)

Avis à la une

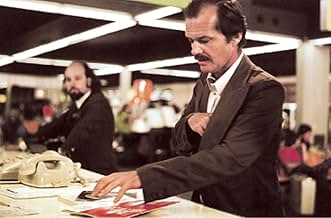

As with the director's most celebrated film, Blowup (1966), The Passenger also deals with the ideas of sight and perception, and with a character - in this case a writer/television reporter - who literally creates his own story as the film progresses. With these factors in places we have an absolutely fascinating piece of work; one filled with endless ideas of interpretation and reinterpretation as we look at the accumulation of character information and the vague scenes that seem to suggest the background of this character in relation to his decisions that come to inform the direction of the plot. With this, we again come back to that central notion of identity and how it governs our journey through life, with the earliest scenes showing Nicholson's character to be lost (both literally and figuratively) in a pensive, limbo-like existence and finding his way out of this torturous situation by attempting to step into the shoes of a completely different character (again, an idea expressed in both the literal and metaphorical sense of the term). These ideas are depicted through Antonioni's fantastic use of time and space, as he places Nicholson, first as an insignificant speck in the midst of the African desert, and then eventually against an ever changing backdrop of exciting and exotic European locales, to literally convey his lack of significance within the world that he inhabits.

Nevertheless, the real enjoyment of the film comes from the eventual realisation that this character makes on the nature of existence and his place within it, and how Antonioni suggests this through his typically rigid and starkly beautiful direction and the actual mechanisms of the plot. As ever with Antonioni's work, the narrative here is structured in a subjective and episodic manner, moving from one scene to the next while offering us snatches of information that we can collect and consider within the perspective of that penultimate scene that seems to put the rest of the film into a kind of context. The director also uses flashbacks and cutaways to scenes that we assume have some precedence over the journey that the character is taking, though again, it could just as easily be connected to the political climate that the film suggests through the documentary footage shot by Nicholson's character before his eventual self-imposed exile from himself. Here, the implication of the film's English title becomes clear, with the character of David Locke becoming a literal passenger in his own life; an empty vessel just drifting through existence with no real interaction, boxed in by the confines of a disintegrating marriage and tied to a job that is slowly sucking the very essence from his being.

Though the film is as minimal and subtle as many of Antonioni's earlier films, such as his grand cinematic gesture, the so-called "alienation trilogy", comprising of the films L'avventura (1960), La Notte (1961) and L'Eclisse (1962), the ultimate themes are incredibly affecting and heartbreaking in their finality; with Locke becoming the representation of the literal lost soul, a ghost in his own life who finds escape through imitation, only to end up reliving the same nightmare as if trapped within some endless loop. For me, it is easy to identify with the ideas here; with the central concept of remaking your own life as someone else entirely - or to live our lives from another perspective - coming back to the often mistaken belief that the grass is always greener on the other side. This notion is suggested throughout the film, from the first very meeting between Locke and the enigmatic Robertson, to that final scene between David and the mysterious girl, in which Locke relates the somewhat heartbreaking parable of the blind man who, after finally regaining his sight on the eve of his 40th birthday, is literally overwhelmed by what a terrible state the world is in.

Metaphors run rife through the film, from Antonioni's visual abstractions within the frame, to the subtle use of wordplay within the script. The ending then ties the whole thing together with a masterful display of technical virtuosity and one of the great, enigmatic questions of Antonioni's career. It is sad, mostly in the same way that the endings of La Notte and L'Eclisse were sad, suggesting a thread of resigned disappointment and the rejection of escape in favour of the easiest option. Ultimately though, the film is deeper, more affecting and more fascinating than any of this particular review might suggest; with Antonioni producing one of his very greatest films, aided by the excellent performances from Nicholson and Maria Schneider, and that continually evasive and hypnotic tone of wandering melancholy, as we move slowly towards that inevitable final, and one of Antonioni's boldest and most purely defined artistic statements.

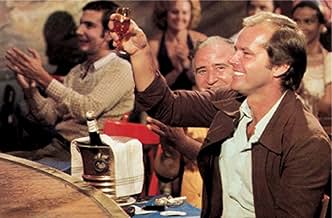

Thirty years later, Michelangelo Antonioni's re-released "The Passenger" is looking very good, and so are Jack Nicholson and Maria Schneider, as the journalist who takes a dead man's identity in the Sahara and the girl he meets in Barcelona who decides to tag along. David Locke (Nicholson) takes the passport of a man named Robertson who he's had a few drinks with in a hotel. Before that we see Locke experience frustration, giving away cigarettes to men in turbans who say nothing, abandoned by a boy guide, dumping a Land Rover stuck in the sand. Later we see films that show as a journalist he was subservient to bad men. Locke has Robertson's appointment book which leads him to Munich, then various points in Spain. He learns Robertson was a committed man taking risks: he sold arms to revolutionaries whose causes he thought were just. He gets a huge down-payment.

Then Locke's wife gets a tape of him talking to Robertson and his passport with Robertson's photo pasted into it -- and she gets the picture.

Changing your identity and using someone else's isn't just an existential act, it's also a criminal one. Locke's gambit is hopeless: he winds up fleeing from himself. The film skillfully gives its action story an existential underpinning. The chase keeps up a rapid pace, like the Bourne franchise, but it has time to contemplate Locke's old and new lives in a metaphorical story he tells Schneider about a blind man that explains how he ends up.

Antonioni is great at little incidentals -- a girl chewing bubblegum, a man reciting in a Gaudi building. And at the end, people coming and going in a desolate plaza outside a bullfighting amphitheater. The locations provide exotic glamor. The camera-work of course is wonderful. In retrospect now one can see this was definitely a culmination for Antonioni. He thought it technically his best film. This is the director's preferred European version, originally released as "Professione: Reporter."

"Professione: reporter", to me, belongs to the most interesting period of Antonioni's career (between the second half of the Sixties and the first of the Seventies). Because in these years the Italian director made his most accessible works: "Blow Up" (1966), "Zabryskie point" (1969) and "Professione: reporter" ("The Passenger", 1974). These films contain more action and more situations. They are neither more commercial nor more mainstream, but they talk about an adventure or a dream.

A journalist in North Africa switches the identity with a dead man who looks like him. He does this to escape from his life and for living a more interesting one. But he'll pay for his choice...

It's difficult to say, but this Antonioni movie (with his recurrent themes and -in a smaller way- times) has a lot of suspense, if I can say so. Once you begin to watch it, you can't give up. The funny thing is that nothing really big or special happens: sometimes it seems a road movie, sometimes it is a typical Antonioni analysis of the society. Jack Nicholson -how young he was at that time!- fills the film, his performance and his expressions are brilliant. It's also interesting the chemistry with Maria Schneider, the lady of "The last tango in Paris" -an actress who never got the fame and the recognition she deserved.

Cinematography is fantastic. But, above all, the big surprise of the film is the final shot: a 7-8 minutes take without cuts, absolute amazing. It's not describable, it's a must!

The camera is always our eye, taking in sweeping panoramas of the North African desert to an architectural tour of European churches and an appreciation of the variegated urban and rural landscapes of Moorish Spain, still showing relics of older invasions, where it all comes together as we literally go from dust to dust. We are the passengers on this existential trip to try and change identities through someone else's travels logging almost as many locations as an outlandish Bond film .

Because so much of the film is dispassionately observational about natural landscape and cityscape, and windswept plazas that provide imitations of nature within a city, it stands up through time, even as the 1975 clothes, hair, TV journalist technology, and, somewhat, male/female relationships, look a bit dated and we can no longer assume that African guerrilla fighters and gun dealers helping them are more noble than the corrupt inheritors of colonialism.

The camera is constantly picking out culture contrasts - camels vs. jeeps, horse-drawn carriages blocking Munich traffic, Gaudi's serpentine architecture vs. Barcelona's modern skyline, a cable car gliding over a shimmering body of water.

And, of course, the very American Jack Nicholson in a very European film, with the many layers of meaning as he plays an adventurous broadcast reporter who ironically tries to escape the truth about himself. His young, sexy, challenging self is surprisingly effective here as we believe both his ethical lapses and his obsession.

Avoiding the narration that a film today would utilize, Antonioni well takes advantage of what now looks fairly primitive tapings of the reporter's past and current interviews to convey background and flashbacks on characters through minimal explication with overlapping sound and gliding visuals. The intertwined story lines constantly re-emphasize the point of not really knowing a person or a culture from the outside, with a repeated refrain of "What do you see?".

Maria Schneider's character skirts just this side of a male fantasy cliché, though Antonioni helped to create the type, and a few subtle plot points save her from total disingenuous sex kitten femme fatale (even as her character shrugs that one plot point is "unlikely"). Nicholson's repeated refrain to her of "What the f* are you doing with me?" takes on different meanings as we know more.

I'm not sure if this 2005 re-release of the director's cut, with supposedly nine minutes that were not in the original U.S. release, is notably pristine, as it wasn't particularly sharp, but the director's trademark crystalline blue sky is still breathtaking and is a must-see in a full screen rather than on DVD. The views practically feel like the old Cinemascope.

A climactic landscape shot brings all the violent, sensual, philosophical and narrative plot and thematic points together in a marvelous way that has been much imitated but is still powerful, as the camera looks out a window at a cool distance in the heat, key events culminate back and forth frantically in front of the camera, in and out of frame, and the camera moves through the bars and is free to roam in ever more close-ups.

Despite its power and polemic against journalism, Professione: Reporter is also an understated movie from start to finish, made for a grown-up audience. Nothing is spelt out for you. However, the movie is strewn throughout with powerful and evocative visual clues, so it's nonetheless up to you as an attentive viewer to pick up (the early scene of Locke's Jeep getting stuck in the African desert sand, anyone?), or even soak them up unconsciously. As with all Antonioni, every shot in this movie is worthy of analysis and admiration. Bergman once said about the Italian that he could create some arresting individual images, but was incapable of stringing them all together in the sequence of a palatable movie: sorry Ingmar, old man - as much as I feel in awe of your craft, you're talking nonsense, here. However, I can't believe Antonioni once had the cheek to say he improvises each scene as he goes along (see his IMDb quotes page). There isn't a chance in hell these meticulously crafted, immaculately framed and composed movies are not also carefully premeditated. Clearly, Antonioni was trying to start a myth about himself along the lines of the one about Mozart composing his music straight onto the page, as dictated by God. In Professione: Reporter, I was especially in awe of the sequence involving the single long take from the window of Locke's last hotel room in an unnamed, dusty Spanish village. Regarding Maria Schneider, it truly is a shame she wasn't the star in a greater number of successful movies. Her ambiguity makes it very difficult to keep one's eyes off her when she's on screen. She looks like a cross between a boy, a girl and something cutely ape-like (I mean it in a good way!).

I would like to warn viewers of the inclusion of footage of a real execution - again, this was a film within the film. Personally, I found it very disturbing, which is why I'm mentioning it here.

Le saviez-vous

- AnecdotesWhen Michelangelo Antonioni received his honorary Oscar in 1995, the Academy asked Jack Nicholson to present it to him.

- GaffesThere are a couple of inaccuracies in the displayed details of Locke's Air Afrique air ticket that was evidently issued in Douala, Cameroon in August 1974. The name of Fort-Lamy (Chad's neighboring capital city) became N'djamena in early 1973, and Paris is written in Italian ("Parigi") which would not have occurred in French-speaking Douala.

- Citations

The Girl: Isn't it funny how things happen? All the shapes we make. Wouldn't it be terrible to be blind?

David Locke: I know a man who was blind. When he was nearly 40 years old, he had an operation and regained his sight.

The Girl: How was it like?

David Locke: At first he was elated... really high. Faces... colors... landscapes. But then everything began to change. The world was much poorer than he imagined. No one had ever told him how much dirt there was. How much ugliness. He noticed ugliness everywhere. When he was blind... he used to cross the street alone with a stick. After he regained his sight... he became afraid. He began to live in darkness. He never left his room. After three years he killed himself.

- Crédits fousLeo, the MGM lion, which normally precedes the opening credits of MGM movies, has been supplanted by "BEGINNING OUR NEXT 50 YEARS". Leo then returns in the center with "GOLDEN ANNIVERSARY" on either side of it.

- Versions alternativesSeven minutes were added to the 2005-2006 re-release version, including a brief shot of a nude Maria Schneider in bed with Jack Nicholson in the Spanish hotel.

- ConnexionsFeatured in Z Channel, une magnifique obsession (2004)

Meilleurs choix

- How long is The Passenger?Alimenté par Alexa

Détails

- Date de sortie

- Pays d’origine

- Site officiel

- Langues

- Aussi connu sous le nom de

- The Passenger

- Lieux de tournage

- Fort Polignac, Algérie(desert scenes, setting: Chad)

- Sociétés de production

- Voir plus de crédits d'entreprise sur IMDbPro

Box-office

- Montant brut aux États-Unis et au Canada

- 620 155 $US

- Week-end de sortie aux États-Unis et au Canada

- 24 157 $US

- 30 oct. 2005

- Montant brut mondial

- 818 936 $US