Ajouter une intrigue dans votre langueThe Globe is a small, but visionary newspaper started by Phineas Mitchell, an editor recently fired by The Star. The two newspapers become enemies, and the Star's ruthless heiress Charity Ha... Tout lireThe Globe is a small, but visionary newspaper started by Phineas Mitchell, an editor recently fired by The Star. The two newspapers become enemies, and the Star's ruthless heiress Charity Hackett decides to eliminate the competition.The Globe is a small, but visionary newspaper started by Phineas Mitchell, an editor recently fired by The Star. The two newspapers become enemies, and the Star's ruthless heiress Charity Hackett decides to eliminate the competition.

- Réalisation

- Scénario

- Casting principal

- Jenny O'Rourke

- (as Tina Rome)

- Barfly

- (non crédité)

- Barfly

- (non crédité)

- Irate Liberty Fund Contributor

- (non crédité)

- Barfly

- (non crédité)

Avis à la une

"Park Row" is small but an engaging and entertaining tribute to American journalism. Under the opening credits we see a huge rolling title that lists about 2,000 American daily newspapers and this story is dedicated to them.

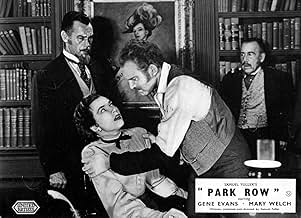

Set in the 1880s New York, the film is about the rivalry between The Globe and The Star. An aspiring newspaper editor (Gene Evans) sets up his own daily The Globe after a man jumps off the Brooklyn Bridge. He struggles to compete with his former employer's (Mary Welch) newspaper The Star, who happens to be in love with him, while the Statue of Liberty is being donated to the U.S. by France.

Unlike Fuller's bleak and lurid "Shock Corridor", "Park Row" is full of reverential optimism and is packed with so much gusto and excitement, featuring some terrific tracking shots that will make your head spin.

Highly recommended.

The plot of "Park Row" is relatively thin. Gene Evans is the newspaper man who becomes the editor of a crusading newspaper in opposition to the more powerful paper from which he's just been fired. It is, in other words, a feelgood movie about a David triumphing over a mean old Goliath, (in this case represented by Mary Welch's excellent performance as the owner of the rival paper), but it's a populist picture with none of the sentimentality that Capra would have brought to it. Indeed, being a Sam Fuller picture, there's a fair amount of violence en route to the happy ending. It also has one of Fuller's best scripts; this is a movie full of crisp dialogue that makes great use of factual material. Amazingly, despite it's substantial critical reputation, it's seldom revived. Time, I think, to rectify that.

I doubt that Fuller was ever well-budgeted. He made do, and boy did he.

The office of the paper is a tight web of cubicles (that are torn down at one point) that cast dark shadows and patches of light. Fuller allows his camera to capture repeated black and white shadow portraits of the characters, their emotion forming the full frame of a shot.

At other points, the camera tours the tiny den as characters move through it as if it were dancing a marvelous ballet Outside is a square, statues of Benjamin Franklin and Horace Greeley and a narrow street allegedly populated by newspapers.

This is all Fuller has to work with, but he makes it work so that even though your subconscious is saying, well, that doesn't look quite realistic, your movie viewing buys in and ignores the tells, absorbing the essence of the scene. Terrific film craft, more than just cinematography.

Can't argue the storyline is up to the filmmaking, but there are touches that Fuller sprinkles throughout that are marvelous.

The newly found paper buys its paper from the butcher. On the floor is a box of unsorted type. It took me back to junior high school in upstate New York, where for a marking period, we had print shop and learned to sort our type and grab it to compose a line in a hand-held device.

There's Otto Morgenthaler, a character borrowed from history, who actually did invent the linotype machine and first use it at the New York Tribune, which is referred to as a competing paper in the film.

The statue of Benjamin Franklin is still there, at the end of Park Row. At one time, the street held The New York World in the Pulitzer Building, Greeley's New York Tribune, The New York Times at #41, the Mail and Express, the Recorder, the Morning Advertiser, and the only other survivor, The Daily News at #25.

In the story, set in 1880s, AP is referred to. The concentration of papers eventually led to the Associated Press, located on Park Row, but that wasn't until 1900.

In the next decade, the landscape was dramatically altered with the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge. It not only cast its shadow over Park Row, but also caused some of its buildings to be demolished for ramp space to the bridge.

Why were the newspapers all there? Strangely, it's never mentioned in the film. Park Row is right around the corner from City Hall, the NYC Police Headquarters and the financial district. That's a pretty good nexus for news.

This one doesn't pop up very often. If you find it, watch and enjoy.

(My ratings are usually to the next highest star. In this case, about 7.5)

The IMDb reviewer, st-shot, who called this movie a "valentine" hit the mark. This valentine has a fair amount going for it, but it's more flawed than faithful. A newspaperman himself (ca. 1930), Fuller prided himself on the historical accuracy of "Park Row" and there is truth behind, if not in, many of the people and events alluded to in the screenplay: The base of the Statue of Liberty, which was unveiled in 1886 when the movie takes place, was indeed partly paid for by a newspaper campaign (Joseph Pulitzer's "New York World"). A Bowery bookie named Steve Brodie did claim to have jumped off the Brooklyn Bridge that same year, and survived to both acclaim and controversy. Linotype was indeed invented by German immigrant Ottmar Mergenthaler in 1886, but it wasn't for a Park Row newspaper, it was for lawyers wanting a way to get legal papers printed faster. The young political cartoonist called "Thomas Guest" is obviously a thinly veiled Thomas Nast, who would have been in his mid-40s and very famous by 1886.

Much of that cinematic license can be forgiven, because the problem isn't the lack of historical accuracy; it's Fuller's proud claim that it WAS accurate. Perhaps he was referring to the typesetting and printing processes he shows in such loving detail-- which certainly are fun and fascinating to see.

Then there's the plot, another big problem. Melodrama was Fuller's Achilles' heel (see THE NAKED KISS for Fuller at his lawless heights) and he pours it on rather thickly here-- injured towheaded kid, heroic journalists, rival editor and publisher as the Clark Kent & Lois Lane of 1886. But, while the movie is more frenetic than energetic, there's enough camera movement and odd angles to establish this firmly as a Fuller film, and therefore worth seeing. Once.

Le saviez-vous

- AnecdotesDirector Samuel Fuller put up his own money to make the movie and lost it all.

- GaffesApproximately 20 minutes into the film, there's a wall calendar showing the date as "1886 June 15 Monday." In 1886 June 15 was a Tuesday.

- Citations

Phineas Mitchell: The press is good or evil according to the character of those who direct it.

- Crédits fousInstead of "The End", the picture ends with "Thirty"; newspaper jargon for "that's all. There ain't no more!"

- ConnexionsFeatured in The Typewriter, the Rifle & the Movie Camera (1996)

Meilleurs choix

- How long is Park Row?Alimenté par Alexa

Détails

Box-office

- Budget

- 200 000 $US (estimé)

- Durée1 heure 23 minutes

- Couleur

- Mixage

- Rapport de forme

- 1.37 : 1