Blanche DuBois, psychologiquement fragile, emménage chez sa soeur à La Nouvelle-Orléans et est tourmentée par son beau-frère brutal alors que tout s'effondre autour d'elle.Blanche DuBois, psychologiquement fragile, emménage chez sa soeur à La Nouvelle-Orléans et est tourmentée par son beau-frère brutal alors que tout s'effondre autour d'elle.Blanche DuBois, psychologiquement fragile, emménage chez sa soeur à La Nouvelle-Orléans et est tourmentée par son beau-frère brutal alors que tout s'effondre autour d'elle.

- Réalisation

- Scénario

- Casting principal

- Récompensé par 4 Oscars

- 22 victoires et 15 nominations au total

James Adamson

- Extra

- (non crédité)

Irene Allen

- Extra

- (non crédité)

Mel Archer

- Foreman

- (non crédité)

Walter Bacon

- Club Patron

- (non crédité)

Dahn Ben Amotz

- Minor Role

- (non crédité)

Avis à la une

Blanche DuBois reminds me of Norma Desmond in Sunset Blvd. (1950). Both characters succumb to their alter egos, and descend into their own worlds of fantasy and half-truths.

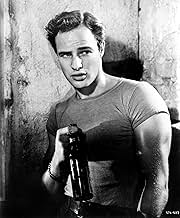

In "A Streetcar Named Desire", Blanche travels from her antebellum roots in Mississippi to New Orleans, to see her sister Stella. But, upon arriving in the Big Easy, Blanche must confront Stella's husband Stanley, a greasy, poker-playing neanderthal lout who knows a thing or two about reality. It's the clash between Blanche's stately delusions and Stanley's gritty realism that soups up the drama in this Tennessee Williams play, converted to film classic by director Elia Kazan.

The drama is absorbing. But the performances of Marlon Brando and Vivien Leigh, as Stanley and Blanche, are what make the film the cinematic powerhouse that it is. Excellent B&W lighting and jazzy background music amplify the seedy, sleazy atmosphere, which adds depth and texture to the story and the acting. And, of course, the claustrophobic, steamy French Quarter makes a perfect setting.

As one would expect for a film derived from a play, "A Streetcar Named Desire" is very talky. Generally, I don't care for films burdened with a ten thousand page script. But this talk-fest is an exception. Overwhelming what I would otherwise consider a weakness, the acting of Brando and Leigh alone are enough to justify a two hour investment, and render an enjoyable and memorable cinematic experience.

In "A Streetcar Named Desire", Blanche travels from her antebellum roots in Mississippi to New Orleans, to see her sister Stella. But, upon arriving in the Big Easy, Blanche must confront Stella's husband Stanley, a greasy, poker-playing neanderthal lout who knows a thing or two about reality. It's the clash between Blanche's stately delusions and Stanley's gritty realism that soups up the drama in this Tennessee Williams play, converted to film classic by director Elia Kazan.

The drama is absorbing. But the performances of Marlon Brando and Vivien Leigh, as Stanley and Blanche, are what make the film the cinematic powerhouse that it is. Excellent B&W lighting and jazzy background music amplify the seedy, sleazy atmosphere, which adds depth and texture to the story and the acting. And, of course, the claustrophobic, steamy French Quarter makes a perfect setting.

As one would expect for a film derived from a play, "A Streetcar Named Desire" is very talky. Generally, I don't care for films burdened with a ten thousand page script. But this talk-fest is an exception. Overwhelming what I would otherwise consider a weakness, the acting of Brando and Leigh alone are enough to justify a two hour investment, and render an enjoyable and memorable cinematic experience.

Now that this filmization of "Streetcar" is over a half century old, it can be looked at in a more objective manner than that of the early fifties. The "classical/traditional" acting style of Vivien Leigh, which was placed in stark contrast to the rest of the production personnel, continues to hold its own brilliantly.

It's probably hard today for some to imagine the strong opposition Leigh's casting faced back in 1950, when this prim actress from England was chosen (mostly by studio chief Jack Warner) over "method" Broadway actress Jessica Tandy.

A goodly number of cast and production people from the hit play directed by Elia Kazan were engaged by the director for the film version, and they were not at all enthusiastic about risking a "clash" of acting styles in the leading, pivotal role of Blanche. Kazan himself was reportedly very pro-Tandy, and quite disappointed in the studio's decision.

Yet, Warner and his staff felt Tandy wasn't that well known to the general movie going public--especially in contrast to Leigh, whose marquee name was by then almost magical. In recent interviews, Kazan admitted that working with Vivien was "a real challenge."

In looking at the film today, however, it's Leigh who emerges as a genuine "star" of this production. True, her facial expressions, vocal inflections and body gestures may be the result of careful, deliberate planning, but so what? It's also the aspect that commands attention and draws the viewer to her portion of the screen throughout this film.

Her southern accent, so well learned and retained from her work as Scarlett in "GWTW," is convincing and very beautiful to hear. It also fits Blanche perfectly, as does Leigh's stylized "choreography," which was undoubtedly retained from her long-running London stage performance.

Not all the combined, formidable talents of "method" giants as Karl Malden, Kim Hunter, Marlon Brando or Kazan can diminish the hypnotic work of Leigh here. It may not have excited "Gadge" Kazan, but it remains a highlight performance in film history (and impressed the Academy enough to bestow an "Oscar" to Vivien.)

It also didn't hurt to have Alex North's pungent score, which remains this composer's finest hour.

It's probably hard today for some to imagine the strong opposition Leigh's casting faced back in 1950, when this prim actress from England was chosen (mostly by studio chief Jack Warner) over "method" Broadway actress Jessica Tandy.

A goodly number of cast and production people from the hit play directed by Elia Kazan were engaged by the director for the film version, and they were not at all enthusiastic about risking a "clash" of acting styles in the leading, pivotal role of Blanche. Kazan himself was reportedly very pro-Tandy, and quite disappointed in the studio's decision.

Yet, Warner and his staff felt Tandy wasn't that well known to the general movie going public--especially in contrast to Leigh, whose marquee name was by then almost magical. In recent interviews, Kazan admitted that working with Vivien was "a real challenge."

In looking at the film today, however, it's Leigh who emerges as a genuine "star" of this production. True, her facial expressions, vocal inflections and body gestures may be the result of careful, deliberate planning, but so what? It's also the aspect that commands attention and draws the viewer to her portion of the screen throughout this film.

Her southern accent, so well learned and retained from her work as Scarlett in "GWTW," is convincing and very beautiful to hear. It also fits Blanche perfectly, as does Leigh's stylized "choreography," which was undoubtedly retained from her long-running London stage performance.

Not all the combined, formidable talents of "method" giants as Karl Malden, Kim Hunter, Marlon Brando or Kazan can diminish the hypnotic work of Leigh here. It may not have excited "Gadge" Kazan, but it remains a highlight performance in film history (and impressed the Academy enough to bestow an "Oscar" to Vivien.)

It also didn't hurt to have Alex North's pungent score, which remains this composer's finest hour.

Blanche Dubois arrives in the French Quarter of New Orleans suffering from a mental tiredness brought on by a series of financial problems that have ended in the family losing their plantation. She has come to stay with her sister, Stella and her husband Stanley Kowalski in their serviceable little apartment. The aggressive and animalistic Stanley immediately marks himself as the opposite of the feminine and refined Blanche and Stella finds herself pulled between the two of them. Stanley suspects all is not as it seems and begins to pry into Blanche's colourful past, even as Blanche spots a way out in the arms of the Mitch, a man captivated by her. However it doesn't take long before the cracks begin to show in the relationships and in Blanche herself.

It almost goes without saying that the writing here is of top-notch quality. The story is a relatively simple character piece that can be summed up in a couple of sentences, however this would do a great injustice to the depth of development and the convincing manner in which the characters are all written and the story told. It is not so much the depth that some of the characters go to, but the complexity that is effortlessly written into them we can see it writ large on them, but not to the point where it seems obvious or uninteresting. Blanche is of course the focus and she is a mess of neurosis barely hidden behind a front of respectability that clearly doesn't convince her anymore than it does Stanley. Mitch is also really well written at first it is comic that he tries to be such a gentleman while having the brute just under the surface, but later his frustration is heavy on his face along with his anger. The overall story is surprisingly, well, "seedy" is the best word that comes to mind. It is in the gutter and no matter what Blanche wants to believe, that is where it stays and the film is right there the whole time.

How Kazan managed it in the early fifties is beyond me, because even now the film is pretty graphic in its violence to women, subject matter and rippling sexuality across pictures and characters. It is a compelling story due to the characters and the manner in which they are delivered Kazan's atmospheric direction really helps; the films feels humid and close, and he has done it all with a basic set and a camera. The lighting throughout is wonderful both in the general atmosphere but also specific touches such as the way Blanche manages to visibly age due to lighting changes when the film has slight chances of tone.

Of course the main reason I keep coming back to this wonderful film is the actors, who take the opportunity and, in many cases, make it so that it is hard to see anyone else playing their roles. Leigh is perfect for the role and gets everything absolutely spot on; she is vulnerable yet self-seeking, confident yet needy, proper yet unstable. Even visually Leigh is convincing in terms of body language but also the fact that she looks the right mix of ages, looking beautiful one moment but worn and defeated the next totally, totally deserved her Oscar. Brando made his name here and even now his performance is electrifying and memorable. He has his big scenes where he gets to play to the back row but he also has moments where he does nothing other than be a presence on screen; no matter what is going on we are watching him because we are as in awe and yet as afraid of his power as Blanche is herself. Together Leigh and Brando dominate the screen and whenever either of them are on screen it is hard to look away. As a result, Kim Hunter sort of gets lost in the background although her performance is still good. Karl Madden is great but again only holds a supporting role and deserved his Oscar for a convincing performance of a well-written character. Of course it is easier to give good performances with great material than with bad material but there have been enough versions of this play around for us to see how lesser actors can fail where this cast soared.

Overall this is a great film that sees so many critical aspects all coming together as one final product. A superb play has undergone a great adaptation that has been seized upon a great cast who deliver a collection of performances that deserve all the praise heaped on them, all directed with a real sense of atmosphere that really delivers a seedy and erotic film both for its time and today. I cannot think of an excuse for people not having seen this film.

It almost goes without saying that the writing here is of top-notch quality. The story is a relatively simple character piece that can be summed up in a couple of sentences, however this would do a great injustice to the depth of development and the convincing manner in which the characters are all written and the story told. It is not so much the depth that some of the characters go to, but the complexity that is effortlessly written into them we can see it writ large on them, but not to the point where it seems obvious or uninteresting. Blanche is of course the focus and she is a mess of neurosis barely hidden behind a front of respectability that clearly doesn't convince her anymore than it does Stanley. Mitch is also really well written at first it is comic that he tries to be such a gentleman while having the brute just under the surface, but later his frustration is heavy on his face along with his anger. The overall story is surprisingly, well, "seedy" is the best word that comes to mind. It is in the gutter and no matter what Blanche wants to believe, that is where it stays and the film is right there the whole time.

How Kazan managed it in the early fifties is beyond me, because even now the film is pretty graphic in its violence to women, subject matter and rippling sexuality across pictures and characters. It is a compelling story due to the characters and the manner in which they are delivered Kazan's atmospheric direction really helps; the films feels humid and close, and he has done it all with a basic set and a camera. The lighting throughout is wonderful both in the general atmosphere but also specific touches such as the way Blanche manages to visibly age due to lighting changes when the film has slight chances of tone.

Of course the main reason I keep coming back to this wonderful film is the actors, who take the opportunity and, in many cases, make it so that it is hard to see anyone else playing their roles. Leigh is perfect for the role and gets everything absolutely spot on; she is vulnerable yet self-seeking, confident yet needy, proper yet unstable. Even visually Leigh is convincing in terms of body language but also the fact that she looks the right mix of ages, looking beautiful one moment but worn and defeated the next totally, totally deserved her Oscar. Brando made his name here and even now his performance is electrifying and memorable. He has his big scenes where he gets to play to the back row but he also has moments where he does nothing other than be a presence on screen; no matter what is going on we are watching him because we are as in awe and yet as afraid of his power as Blanche is herself. Together Leigh and Brando dominate the screen and whenever either of them are on screen it is hard to look away. As a result, Kim Hunter sort of gets lost in the background although her performance is still good. Karl Madden is great but again only holds a supporting role and deserved his Oscar for a convincing performance of a well-written character. Of course it is easier to give good performances with great material than with bad material but there have been enough versions of this play around for us to see how lesser actors can fail where this cast soared.

Overall this is a great film that sees so many critical aspects all coming together as one final product. A superb play has undergone a great adaptation that has been seized upon a great cast who deliver a collection of performances that deserve all the praise heaped on them, all directed with a real sense of atmosphere that really delivers a seedy and erotic film both for its time and today. I cannot think of an excuse for people not having seen this film.

When the history of American theater is written for the 20th Century the two most prominent names will be Eugene O'Neill and Tennessee Williams. Both men pushed the exploration of the human soul to the very limit in their work. Writing drama will never be the same because of the work of these two men.

Williams's masterpiece is A Streetcar Named Desire which ran over 860 performances in three years. When Warner Brothers bought the film rights, they did the highly unusual thing of bringing almost the entire Broadway cast over. That included Marlon Brando for whom this was his second film. Brando was not a movie name yet and the decision was made to recast the female lead with Vivien Leigh instead of Jessica Tandy who played Blanche Dubois on Broadway.

In doing so this gave Vivien Leigh the very unique position of having played opposite the two men who are held up as male acting icons for the last century, Marlon Brando and Leigh's husband at the time Laurence Olivier. Certainly Blanche Dubois was unlike anything she ever did opposite Olivier.

In fact Blanche is opposite that other southern belle that Leigh got her first Oscar for, Scarlett O'Hara. Scarlett may come on like a spoiled brat at first, but she turns out to be made of some real stern stuff when the chips are down.

Blanche Dubois however retreats into her own fantasies when trouble brews. She's left the plantation home in a small Mississippi town where she doubles as an English teacher and comes to live with her sister Stella and her husband Stanley Kowalski.

Brando is Kowalski and for years impressionists did him by yelling from the pit of their abdomens, "STELLA, STELLA." That is until The Godfather and then they stuffed their cheeks and said how one day a favor would be asked in return.

But impressionists only make a living because of the impressions made by the players. On Broadway and Hollywood, Stanley Kowalski made Marlon Brando a superstar and an icon for a couple of generations. Kowalski as done by Brando is a force of nature, primeval impulses that bubble to the surface in all of us sometimes.

Kim Hunter as Stella Kowalski and Karl Malden as Mitch Mitchell also won Oscars in the Supporting categories to go with Leigh's. Hunter is a torn women fighting both suspicions about her husband and her sister. The real reason why Blanche has come to live with them and the affect her silly flirtations are having on her husband and their marriage.

Malden as Mitchell starts out as passive and as nice as Jim Connor, the gentleman caller from that other Tennessee Williams masterpiece, A Glass Menagerie. But he proves to be something less than meets the eye in his dealings with Leigh.

A Streetcar Named Desire won all kinds of Awards, the three acting Oscars, one for Elia Kazan as Best Director and a whole bunch of technical ones. But An American In Paris won for Best Picture and Hollywood decided young Brando could wait for his and they gave it that year to Humphrey Bogart for The African Queen.

This film is still the best adaption to the screen of a Tennessee Williams play and is an absolute must to see.

Williams's masterpiece is A Streetcar Named Desire which ran over 860 performances in three years. When Warner Brothers bought the film rights, they did the highly unusual thing of bringing almost the entire Broadway cast over. That included Marlon Brando for whom this was his second film. Brando was not a movie name yet and the decision was made to recast the female lead with Vivien Leigh instead of Jessica Tandy who played Blanche Dubois on Broadway.

In doing so this gave Vivien Leigh the very unique position of having played opposite the two men who are held up as male acting icons for the last century, Marlon Brando and Leigh's husband at the time Laurence Olivier. Certainly Blanche Dubois was unlike anything she ever did opposite Olivier.

In fact Blanche is opposite that other southern belle that Leigh got her first Oscar for, Scarlett O'Hara. Scarlett may come on like a spoiled brat at first, but she turns out to be made of some real stern stuff when the chips are down.

Blanche Dubois however retreats into her own fantasies when trouble brews. She's left the plantation home in a small Mississippi town where she doubles as an English teacher and comes to live with her sister Stella and her husband Stanley Kowalski.

Brando is Kowalski and for years impressionists did him by yelling from the pit of their abdomens, "STELLA, STELLA." That is until The Godfather and then they stuffed their cheeks and said how one day a favor would be asked in return.

But impressionists only make a living because of the impressions made by the players. On Broadway and Hollywood, Stanley Kowalski made Marlon Brando a superstar and an icon for a couple of generations. Kowalski as done by Brando is a force of nature, primeval impulses that bubble to the surface in all of us sometimes.

Kim Hunter as Stella Kowalski and Karl Malden as Mitch Mitchell also won Oscars in the Supporting categories to go with Leigh's. Hunter is a torn women fighting both suspicions about her husband and her sister. The real reason why Blanche has come to live with them and the affect her silly flirtations are having on her husband and their marriage.

Malden as Mitchell starts out as passive and as nice as Jim Connor, the gentleman caller from that other Tennessee Williams masterpiece, A Glass Menagerie. But he proves to be something less than meets the eye in his dealings with Leigh.

A Streetcar Named Desire won all kinds of Awards, the three acting Oscars, one for Elia Kazan as Best Director and a whole bunch of technical ones. But An American In Paris won for Best Picture and Hollywood decided young Brando could wait for his and they gave it that year to Humphrey Bogart for The African Queen.

This film is still the best adaption to the screen of a Tennessee Williams play and is an absolute must to see.

"Streetcar Named Desire" is an exceptional film, thanks to three essential components: (1) the superb acting ability of its two leads, Vivien Leigh and Marlon Brando, as well as that of the supporting cast, small in number but huge in its combined dramatic power, (2) an excellent screenplay by the original playwright, Tennessee Williams, that is packed from beginning to end with explosive, conflict driven dialogue, and (3) the brilliant direction of Elia Kazan who so skillfully brings the play to the screen.

In its legendary opening, Blanche DuBois (Vivien Leigh) emerges from a cloud of locomotive smoke and is helped onto a streetcar by a perfect stranger, a sailor. This simple act neatly ties the film's beginning to Blanche's final, heartbreaking line, "I have always depended upon the kindness of strangers". She, as the central character, is lost in the big city, and she becomes more and more hopelessly adrift in the world as the film approaches its very tragic end.

Broke and friendless, Blanche lands in New Orleans where her sister, Stella (Kim Hunter) lives with her coarse, crude husband, Stanley Kowalski (Brando). Having lost her ancestral home on account of family-related debt and having been dismissed under vague circumstances from her position as a high school English teacher in the small Mississippi town from where she came, she has no other place to go at a time of dire need.

Although Stella is genuinely concerned about Blanche's declining physical and mental state, the shabby apartment where she lives with Stanley consists of two small rooms, barely enough space for the Kowalskis even without Stanley's regular poker group, which seems to park itself there at every available opportunity. What makes matters worse is Stanley's loud and boisterous personality. From the start, Stanley resents the presence of Blanche, which he views as an unwanted, disruptive invasion of his marriage and his home. He regards her with total distrust and disdain. Another reviewer here interpreted this as a cultural clash between the old and the new South, and I think that is a very astute observation. In any case, Stanley is totally unsympathetic to Blanche's plight and looks upon her with nothing but suspicion and contempt.

Blanche is trapped in the claustrophobic and confining prison of the dingy Kowalski apartment. For one, fleeting moment, she believes that Mitch (Karl Malden), Stanley's poker buddy and co-worker, stands as her one bright hope of liberation from the walls that continue to close around her, but he turns out to be anything but her desperately needed "knight in shining armor". Tragically, Mitch, a weak individual who is still dominated by a strong mother well into his adulthood, is the last person with the ability to give Blanche the love and strength that she so urgently needs and to whisk her away from the stifling, debilitating atmosphere of the Kowalski dungeon. Blanche's one, last hope for personal redemption soon fades away forever.

I read that, under different circumstances, the lead roles could have been awarded to Olivia de Haviland and John Garfield. As much as I like them both, this would have been a much different movie with them as the leads. Ms. Leigh, a stunning Englishwoman who managed to score two Oscars for playing two iconic, southern American characters, portrays a mentally declining Blanche with great depth and compassion. As to Mr. Brando's brutish and obnoxious Stanley, you've got to see him in action to appreciate his magnificent performance. As in the case of his Terry Malloy in "On the Waterfront", I don't believe that Stanley's most famous lines from this film would be among the most imitated to this day if they weren't delivered so dynamically by Brando in the first place. "Hey, Stel-la!" Sorry. I just couldn't help myself.

While Brando was beaten out of the Oscar by Humphrey Bogart in "African Queen" (not my favorite Bogey movie by a long shot), Leigh, Malden, and Hunter swept the awards for their performances here and deservedly so. The memorable role of feisty neighbor Eunice also launched Pat Hillias's successful career throughout the golden age of television during the 1950's until her tragic and untimely death in 1960.

If you want to watch an unforgettable rendering of a strong, intense script that is worthy of such a talented cast and director, don't miss this one.

In its legendary opening, Blanche DuBois (Vivien Leigh) emerges from a cloud of locomotive smoke and is helped onto a streetcar by a perfect stranger, a sailor. This simple act neatly ties the film's beginning to Blanche's final, heartbreaking line, "I have always depended upon the kindness of strangers". She, as the central character, is lost in the big city, and she becomes more and more hopelessly adrift in the world as the film approaches its very tragic end.

Broke and friendless, Blanche lands in New Orleans where her sister, Stella (Kim Hunter) lives with her coarse, crude husband, Stanley Kowalski (Brando). Having lost her ancestral home on account of family-related debt and having been dismissed under vague circumstances from her position as a high school English teacher in the small Mississippi town from where she came, she has no other place to go at a time of dire need.

Although Stella is genuinely concerned about Blanche's declining physical and mental state, the shabby apartment where she lives with Stanley consists of two small rooms, barely enough space for the Kowalskis even without Stanley's regular poker group, which seems to park itself there at every available opportunity. What makes matters worse is Stanley's loud and boisterous personality. From the start, Stanley resents the presence of Blanche, which he views as an unwanted, disruptive invasion of his marriage and his home. He regards her with total distrust and disdain. Another reviewer here interpreted this as a cultural clash between the old and the new South, and I think that is a very astute observation. In any case, Stanley is totally unsympathetic to Blanche's plight and looks upon her with nothing but suspicion and contempt.

Blanche is trapped in the claustrophobic and confining prison of the dingy Kowalski apartment. For one, fleeting moment, she believes that Mitch (Karl Malden), Stanley's poker buddy and co-worker, stands as her one bright hope of liberation from the walls that continue to close around her, but he turns out to be anything but her desperately needed "knight in shining armor". Tragically, Mitch, a weak individual who is still dominated by a strong mother well into his adulthood, is the last person with the ability to give Blanche the love and strength that she so urgently needs and to whisk her away from the stifling, debilitating atmosphere of the Kowalski dungeon. Blanche's one, last hope for personal redemption soon fades away forever.

I read that, under different circumstances, the lead roles could have been awarded to Olivia de Haviland and John Garfield. As much as I like them both, this would have been a much different movie with them as the leads. Ms. Leigh, a stunning Englishwoman who managed to score two Oscars for playing two iconic, southern American characters, portrays a mentally declining Blanche with great depth and compassion. As to Mr. Brando's brutish and obnoxious Stanley, you've got to see him in action to appreciate his magnificent performance. As in the case of his Terry Malloy in "On the Waterfront", I don't believe that Stanley's most famous lines from this film would be among the most imitated to this day if they weren't delivered so dynamically by Brando in the first place. "Hey, Stel-la!" Sorry. I just couldn't help myself.

While Brando was beaten out of the Oscar by Humphrey Bogart in "African Queen" (not my favorite Bogey movie by a long shot), Leigh, Malden, and Hunter swept the awards for their performances here and deservedly so. The memorable role of feisty neighbor Eunice also launched Pat Hillias's successful career throughout the golden age of television during the 1950's until her tragic and untimely death in 1960.

If you want to watch an unforgettable rendering of a strong, intense script that is worthy of such a talented cast and director, don't miss this one.

Le saviez-vous

- AnecdotesAs the film progresses, the set of the Kowalski apartment actually gets smaller to heighten the suggestion of Blanche's increasing claustrophobia.

- GaffesWhen Stanley comes back from taking Stella to the hospital, he is looking for a bottle opener. He finds it on the mantelpiece, shakes up a bottle of beer, and opens it. The beer foams up and spills on his trousers. But if you watch at the moment when he swings himself up to sit on the table - before he opens the bottle - you can see that the front of his trousers are already wet. Apparently they re-shot it without him changing into dry trousers.

- Versions alternativesThe scene in which Blanche and Stanley first meet was edited a bit to take out some of the sexual tension that both had towards each other when the film was first released in 1951. In 1993, this footage was restored in the "Original Director's Version" of the film. The three minutes of newly-added footage sticks out from the rest of the film because Warner Brothers did not bother to restore these extra film elements along with the rest of the movie, leaving them very scratchy due to deterioration.

- ConnexionsEdited into Un Américain nommé Kazan (2018)

- Bandes originalesIt's Only a Paper Moon

(1933) (uncredited)

Music by Harold Arlen

Lyrics by E.Y. Harburg and Billy Rose

Sung by Vivien Leigh while doing her hair

Meilleurs choix

Connectez-vous pour évaluer et suivre la liste de favoris afin de recevoir des recommandations personnalisées

Détails

- Date de sortie

- Pays d’origine

- Langues

- Aussi connu sous le nom de

- Un tranvía llamado Deseo

- Lieux de tournage

- Nouvelle-Orléans, Louisiane, États-Unis(railway station)

- Sociétés de production

- Voir plus de crédits d'entreprise sur IMDbPro

Box-office

- Budget

- 1 800 000 $US (estimé)

- Montant brut mondial

- 54 695 $US

- Durée2 heures 2 minutes

- Couleur

- Rapport de forme

- 1.37 : 1

Contribuer à cette page

Suggérer une modification ou ajouter du contenu manquant

Lacune principale

What was the official certification given to Un tramway nommé désir (1951) in Japan?

Répondre