Un homme accepte un travail dans un asile dans l'espoir de libérer sa femme qui y est internée.Un homme accepte un travail dans un asile dans l'espoir de libérer sa femme qui y est internée.Un homme accepte un travail dans un asile dans l'espoir de libérer sa femme qui y est internée.

- Réalisation

- Scénario

- Casting principal

Avis à la une

Very few Japanese films exist from the silent period. In fact, statistics show that only 1% of around 7,000 productions are represented in the a catalogue of the silent cycle. Director Teinosuke Kinugasa's Kurutta Ippeji (also known as A Page of Madness) was thought lost (and perhaps forgotten) until he himself discovered a print in a warehouse in 1971. He diligently produced a new music soundtrack and re-released it. This is the first example of a silent film from Japan, and have to say that the world should be thankful that Kinugasa discovered this avant- garde little master work.

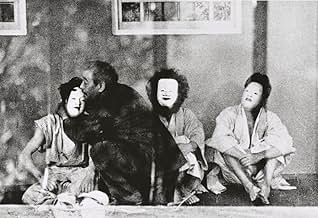

The film was produced with an avant garde group of artists, known as Shinkankak-ha (School of New Perceptions), an experimental art movement that rejected naturalism, or realism, and was highly influenced by European art movements such as Expressionism, Dada, and Cubism, and evidently uses the techniques found in Soviet Montage, particularly Sergei Eisenstein - fundamentally, as this project deals with madness, it would be easy to draw parallels with Robert Weine's seminal horror film Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (1920). What the art trope bring to this extreme nightmare are those exaggerated, pointed and alarmist movements like the expressionist acting styles being used in European film and stage work - but happens to find its own stylistic flourishes, and colloquial "voice" (for want of a better word).

Kurutta ippeji's simplistic story focuses on a man (Masuo Inoue) whom has taken a job as a janitor in an asylum, so that he may be close to his wife (Yoshie Nakagawa), who has been condemned. His aim is to aid in her escape from the dogmatic institution. However, when the break-out is orchestrated, her madness has enveloped her, and she is unwilling to leave with her husband. The couples daughter (Ayako Iijima) visits the asylum to advise her mother of her engagement, which leads to a maelstrom of fantastically abstract flashbacks, giving light to the reasons the mother is condemned.

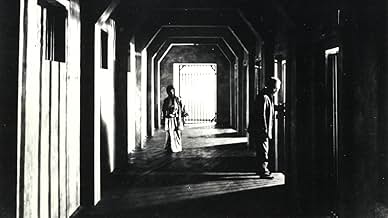

The films style is so incredibly complex and technically brilliant. In the opening sequence, the jarring compositions (both beautiful and haunting), superimposition's, and quick montage editing, creates an assault on the senses that is difficult to break away from - torrential rain falls the scenery in shots of the asylum, expressionist compositions of wind-battered tree branches clashing with windows, and the sight of a woman riddled in madness. The use of superimposition becomes greater as the film moves into crescendo, and these layers portray climatically the merger of madness and modernity. Do we witness the ghosts that haunt the corridors of the asylum? Or are these the devastating spectre's of modernity, and the destruction of tradition? An ironic speculation perhaps, considering the mechanics of cinema production and exhibition.

To a modern audience, silent cinema is often a difficult watch. This film is of particular note for this argument. Kurutta ippeji has no title cards describing dialogue, or internal action, which makes it difficult to follow at times. But as with all 1920's Japanese cinema, the films were always accompanied by narration - a storyteller known colloquially as a benshi. But this small infraction does not hamper an incredibly dazzling piece of early experimental cinema, and one that should be viewed by any film enthusiast, at least for posterity - if not for a formative education on the stylistic diversity of film as art.

www.the-wrath-of-blog.blogspot.com

The film was produced with an avant garde group of artists, known as Shinkankak-ha (School of New Perceptions), an experimental art movement that rejected naturalism, or realism, and was highly influenced by European art movements such as Expressionism, Dada, and Cubism, and evidently uses the techniques found in Soviet Montage, particularly Sergei Eisenstein - fundamentally, as this project deals with madness, it would be easy to draw parallels with Robert Weine's seminal horror film Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (1920). What the art trope bring to this extreme nightmare are those exaggerated, pointed and alarmist movements like the expressionist acting styles being used in European film and stage work - but happens to find its own stylistic flourishes, and colloquial "voice" (for want of a better word).

Kurutta ippeji's simplistic story focuses on a man (Masuo Inoue) whom has taken a job as a janitor in an asylum, so that he may be close to his wife (Yoshie Nakagawa), who has been condemned. His aim is to aid in her escape from the dogmatic institution. However, when the break-out is orchestrated, her madness has enveloped her, and she is unwilling to leave with her husband. The couples daughter (Ayako Iijima) visits the asylum to advise her mother of her engagement, which leads to a maelstrom of fantastically abstract flashbacks, giving light to the reasons the mother is condemned.

The films style is so incredibly complex and technically brilliant. In the opening sequence, the jarring compositions (both beautiful and haunting), superimposition's, and quick montage editing, creates an assault on the senses that is difficult to break away from - torrential rain falls the scenery in shots of the asylum, expressionist compositions of wind-battered tree branches clashing with windows, and the sight of a woman riddled in madness. The use of superimposition becomes greater as the film moves into crescendo, and these layers portray climatically the merger of madness and modernity. Do we witness the ghosts that haunt the corridors of the asylum? Or are these the devastating spectre's of modernity, and the destruction of tradition? An ironic speculation perhaps, considering the mechanics of cinema production and exhibition.

To a modern audience, silent cinema is often a difficult watch. This film is of particular note for this argument. Kurutta ippeji has no title cards describing dialogue, or internal action, which makes it difficult to follow at times. But as with all 1920's Japanese cinema, the films were always accompanied by narration - a storyteller known colloquially as a benshi. But this small infraction does not hamper an incredibly dazzling piece of early experimental cinema, and one that should be viewed by any film enthusiast, at least for posterity - if not for a formative education on the stylistic diversity of film as art.

www.the-wrath-of-blog.blogspot.com

10mjneu59

Film history has been negligent in recognizing this landmark silent drama, made in 1926 by pioneering Japanese director Teinosuke Kinugasa, but unknown until 1971, when a surviving print was (literally) unearthed in the director's garden shed. The film was produced in an isolated creative environment far removed from any foreign influence, but is nevertheless a masterpiece of imagery and editing, revealing a stunning visual flair and employing montage techniques as skillfully as anyone since Eisenstein. It tells a powerful, hallucinatory story of a janitor in an insane asylum who wants desperately to help his inmate wife after she attempts suicide, and like Murnau's 'The Last Laugh' unfolds without the crutch of intertitles. The film has aged remarkable little after the better part of a century in limbo, but since its belated rediscovery has yet to earn the acclaim and evaluation it deserves.

Kurutta Ippeji offers a view on the distorted perspective of a troubled janitor in a mental asylum. As a proof of concept, it shows that experimental cinematic techniques can affect the way narration is perceived by the viewer - here, the visual elements contribute to how the viewer experiences the characters' mental state. As an experiment, the movie possibly even makes a stronger case than the comparably surreal Hausu (1977), which is partly imbalanced in its style. However, due to the poor visual quality and the lack of functional storytelling, this experimental feature can't be easily recommended to people looking for a more conventional feature.

Overall 7/10

Full Review on movie-discouse.blogspot.com

Kurutta ippêji (1926)

*** (out of 4)

Bizarre Japanese horror film has a man taking a janitor job at an asylum so that he can be closer to his wife who was committed after trying to kill their child. Had Luis Bunuel been bore in Japan and started making movies in 1926 then I'm guessing the final product would have came out looking like this thing. Lost for decades, it's easy to see why this film was never discovered but now that it's making its way around, it seems like this is destined to become something of a cult favorite to silent and horror fans. There's no straight story being told here, instead it's more avant-garde as we get all sorts of surreal images. We get the basic story but everything else is either told in flashback or through extra fast editing that helps build up the insanity of the lead character. Director Teinosuke Kinugasa really wants to get inside the mind of the insane and I think he does a pretty good job with it. At just 59-minutes the film moves at a pretty fast rate and a lot of this can be credited to the editing. I thought that the editing was the real star of the movie as it's done in such a fashion that you often see something but then you question what it was that you actually saw. You also have to try and keep up with what's going on and everything is happening so fast that you can see that the director was trying to use this to make the viewer feel what the characters were feeling being the asylum walls. There aren't any intertitles, which just adds to the visual image and the music score (done in the 70s) fits the film very well.

*** (out of 4)

Bizarre Japanese horror film has a man taking a janitor job at an asylum so that he can be closer to his wife who was committed after trying to kill their child. Had Luis Bunuel been bore in Japan and started making movies in 1926 then I'm guessing the final product would have came out looking like this thing. Lost for decades, it's easy to see why this film was never discovered but now that it's making its way around, it seems like this is destined to become something of a cult favorite to silent and horror fans. There's no straight story being told here, instead it's more avant-garde as we get all sorts of surreal images. We get the basic story but everything else is either told in flashback or through extra fast editing that helps build up the insanity of the lead character. Director Teinosuke Kinugasa really wants to get inside the mind of the insane and I think he does a pretty good job with it. At just 59-minutes the film moves at a pretty fast rate and a lot of this can be credited to the editing. I thought that the editing was the real star of the movie as it's done in such a fashion that you often see something but then you question what it was that you actually saw. You also have to try and keep up with what's going on and everything is happening so fast that you can see that the director was trying to use this to make the viewer feel what the characters were feeling being the asylum walls. There aren't any intertitles, which just adds to the visual image and the music score (done in the 70s) fits the film very well.

A Page of Madness is an expressionistic Japanese film that has not gotten the attention it deserves. I was introduced to the film through the fifteen part documentary series The Story of Film an Odyssey. Fortunately, a friend had dubbed the silent film off of Turner Classic Movies during one of its infrequent showings.

The clip in The Story of a Film an Odyssey looked like some mad movie genius had crossed the set designs from a German expressionist film with the fast edits of a classic Russian work. This clip was from the attention grabbing opening of A Page of Madness. A janitor wanders an insane asylum at night during a storm. The storm has a strange effect on the patients and, presumably, the attendant. The edits are fast, conveying mystery and terror like in a horror film. This sequence (and a sequence at the climax) is nothing short of brilliance.

From here the film turns to a narrative, although an oblique one. This clerk or janitor seems to have an unhealthy fixation on one of the female patients. . . and more of one for this patient's daughter. The janitor clearly knew this family before the mother was committed. IMDb says that the woman is the janitor's wife. I am not doubting this, but the film is not clear on this point. What is clear is that the janitor is suffering from a lack of love. This janitor is not the only one. One patient is compelled to dance suggestively and nearly starts a riot. By contrast, the doctors appear clinical and ineffectual. As the film goes along, the protagonist's mental state seems to wane.

Much about the plot is unclear. Many Japanese silent were narrated by a spokesman in the theater. This may have been the case with A Page of Madness; thus, some of the ambiguity would have been explained by the live narrator. I prefer to think the ambiguity was deliberate and never explained. The film has a wonderful sense of mystery to it. I don't want any more of an explanation. I (and probably most film fans) watch a lot of movies that are merely fair. These films are watchable, but they do not stay in one's memory. That is why A Page of Madness is so stunning. It kicks the door down and announces itself to the world. I feel less like a reviewer than a herald for a lost classic. Are you listening Criterion?

The clip in The Story of a Film an Odyssey looked like some mad movie genius had crossed the set designs from a German expressionist film with the fast edits of a classic Russian work. This clip was from the attention grabbing opening of A Page of Madness. A janitor wanders an insane asylum at night during a storm. The storm has a strange effect on the patients and, presumably, the attendant. The edits are fast, conveying mystery and terror like in a horror film. This sequence (and a sequence at the climax) is nothing short of brilliance.

From here the film turns to a narrative, although an oblique one. This clerk or janitor seems to have an unhealthy fixation on one of the female patients. . . and more of one for this patient's daughter. The janitor clearly knew this family before the mother was committed. IMDb says that the woman is the janitor's wife. I am not doubting this, but the film is not clear on this point. What is clear is that the janitor is suffering from a lack of love. This janitor is not the only one. One patient is compelled to dance suggestively and nearly starts a riot. By contrast, the doctors appear clinical and ineffectual. As the film goes along, the protagonist's mental state seems to wane.

Much about the plot is unclear. Many Japanese silent were narrated by a spokesman in the theater. This may have been the case with A Page of Madness; thus, some of the ambiguity would have been explained by the live narrator. I prefer to think the ambiguity was deliberate and never explained. The film has a wonderful sense of mystery to it. I don't want any more of an explanation. I (and probably most film fans) watch a lot of movies that are merely fair. These films are watchable, but they do not stay in one's memory. That is why A Page of Madness is so stunning. It kicks the door down and announces itself to the world. I feel less like a reviewer than a herald for a lost classic. Are you listening Criterion?

Le saviez-vous

- AnecdotesThis film was deemed lost for more than forty years, but it was rediscovered by its director, Teinosuke Kinugasa, in a rice cans in 1971.

- Versions alternativesReissued in Japan in 1973 with musical score replacing original benshi.

- ConnexionsFeatured in The Story of Film: An Odyssey: The Golden Age of World Cinema (2011)

Meilleurs choix

Connectez-vous pour évaluer et suivre la liste de favoris afin de recevoir des recommandations personnalisées

- How long is A Page of Madness?Alimenté par Alexa

Détails

- Date de sortie

- Pays d’origine

- Langues

- Aussi connu sous le nom de

- A Page of Madness

- Lieux de tournage

- Kyoto, Japon(Studio)

- Sociétés de production

- Voir plus de crédits d'entreprise sur IMDbPro

Box-office

- Budget

- 20 000 JPY (estimé)

- Durée1 heure 10 minutes

- Couleur

- Mixage

- Rapport de forme

- 1.33 : 1

Contribuer à cette page

Suggérer une modification ou ajouter du contenu manquant