NOTE IMDb

7,2/10

22 k

MA NOTE

Ajouter une intrigue dans votre langueA group of bandits stage a brazen train hold-up, only to find a determined posse hot on their heels.A group of bandits stage a brazen train hold-up, only to find a determined posse hot on their heels.A group of bandits stage a brazen train hold-up, only to find a determined posse hot on their heels.

- Réalisation

- Scénario

- Casting principal

- Récompenses

- 1 victoire au total

Gilbert M. 'Broncho Billy' Anderson

- Bandit

- (non crédité)

- …

A.C. Abadie

- Sheriff

- (non crédité)

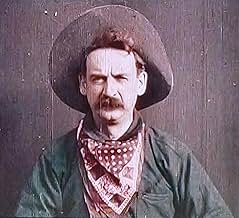

Justus D. Barnes

- Bandit Who Fires at Camera

- (non crédité)

Walter Cameron

- Sheriff

- (non crédité)

John Manus Dougherty Sr.

- Fourth Bandit

- (non crédité)

Donald Gallaher

- Little Boy

- (non crédité)

Shadrack E. Graham

- Child

- (non crédité)

Frank Hanaway

- Bandit

- (non crédité)

Adam Charles Hayman

- Bandit

- (non crédité)

Robert Milasch

- Trainman

- (non crédité)

- …

Marie Murray

- Dance-Hall Dancer

- (non crédité)

Frederick T. Scott

- Man

- (non crédité)

Mary Snow

- Little Girl

- (non crédité)

Avis à la une

It's hard to assign "The Great Train Robbery" a rating, as it shouldn't really be watched as a film the way we watch films now. But from a historical perspective, it's fascinating, and is an excellent example of the use of film editing, an art form then in its infancy and now an award category recognized every year at the Oscars.

Before this movie, it wasn't customary to tell multiple story lines simultaneously, but here, various activities going on in different locations are intercut to create suspense. D.W. Griffith would use this technique much more ambitiously (and combine it with many other developing film techniques) in "The Birth of a Nation" over ten years later, but credit must be given to "Train Robbery" for blazing a trail.

Also, this is the movie famous for the shot of an outlaw shooting a gun directly at the camera. I can't imagine what effect this had on audiences at the time, who were probably diving behind their chairs for cover.

Grade: A

Before this movie, it wasn't customary to tell multiple story lines simultaneously, but here, various activities going on in different locations are intercut to create suspense. D.W. Griffith would use this technique much more ambitiously (and combine it with many other developing film techniques) in "The Birth of a Nation" over ten years later, but credit must be given to "Train Robbery" for blazing a trail.

Also, this is the movie famous for the shot of an outlaw shooting a gun directly at the camera. I can't imagine what effect this had on audiences at the time, who were probably diving behind their chairs for cover.

Grade: A

This film, often lauded as one of the first movies to include a linear narrative within its running time, came out of the Edison company over a hundred years ago, following their experiments in the previous decades with shorter topical pieces such as cockfighting, dancers, and other limited scenarios.

'The Great Train Robbery' is a simple enough story - a train is robbed, there is a shoot-out. The interesting scenes for me were the ones where the passengers are held at gunpoint while their valuables are collected, the shoot-out with its hand-coloured bursts of gunfire, and the famous final shot where a gun is fired directly at the audience. Not too frightening now, but back in those days this was quite an innovation.

Historically important and with a basic plot still in use today, this film holds significant interest for a wide audience (and will take less than a quarter of an hour of your time to view).

'The Great Train Robbery' is a simple enough story - a train is robbed, there is a shoot-out. The interesting scenes for me were the ones where the passengers are held at gunpoint while their valuables are collected, the shoot-out with its hand-coloured bursts of gunfire, and the famous final shot where a gun is fired directly at the audience. Not too frightening now, but back in those days this was quite an innovation.

Historically important and with a basic plot still in use today, this film holds significant interest for a wide audience (and will take less than a quarter of an hour of your time to view).

"The Great Train Robbery" was the most successful film to date, and its distribution preceded and eventually coincided with the spread of Nickelodeons across America. It didn't instantly create the Western genre; instead, it was part of and led to a spew of crime pictures--a genre begun in England. (G.M. "Billy Bronco" Anderson, who was somewhat of an assistant director on the film, would largely invent the movie Western a few years later after leaving the Edison Company, however.) Although the plot isn't very exciting today, the film remains a landmark in film history--mostly for its narrative structure. It's also notable how matter-of-fact, "realistic" and violent the film is for its time--being detailed and rather objective in its following of the details of the crime (what Neil Harris calls "an operational aesthetic"). The story film was already established by 1903 but was still in its infancy. Filmmakers were still experimenting with how to tell a narrative, and Porter was one of early film's greatest innovators, as well as an astute student of film.

Throughout his film-making career, Porter was strongly influenced by contemporary British and French films, which he would have ready access to since the Edison Company regularly duped them. His "Uncle Josh at the Moving Picture Show" is a rip-off of Robert Paul's "The Countryman and the Cinematograph." "The Gay Shoe Clerk" is a revision of George Smith's "As Seen Through a Telescope." Porter also introduced intertitles to American cinema in "Uncle Tom's Cabin," having seen them in some of Smith's films. "Life of an American Fireman" reflects James Williamson's "Fire!" The temporal replay in that film was influenced by Georges Méliès's temporal replay of the Moon landing in "Le Voyage dans la lune." "Dream of a Rarebit Fiend" also owes plenty to Méliès.

"The Great Train Robbery" followed a recently created genre of crime and chase films begun in England. "The Daring Daylight Robbery" was especially of influence, as was, it is said by historians, a 1903 film called "The Robbery of the Mail Coach." "The Great Train Robbery" is also based on a play of the same title by Scott Marble. News of real train robberies also served as inspiration according to the Edison catalogue. Anyhow, with the exception of wholesale rip-offs, it's not discourageable that Porter learned from other films and adopted techniques and style from them for his own. He is worthy of history's praise for being such an avid student of film and one of the more active filmmakers of his time to develop film grammar.

Some film historians and critics say that Porter's work was uneven, that "The Grain Train Robbery" and perhaps one or two other films were a happenstance success, or fluke. Someone was bound to figure out the techniques of narrative as story films became more complex--confronting such problems as spatially separate actions and the continuity of action. I've seen a good share of Porter's work, however, and it's apparent that he was usually experimenting. He wasn't consistent like Méliès, which is good because his work becomes stale. Porter's previous experiments in editing resulted in this, his most accomplished story film and greatest success.

There are a few special effects in "The Great Train Robbery," as others have mentioned. It's nothing new: double-exposure matte work for the shot of the train outside the window and for the outside of the moving train's door, hand coloring, in addition to stopping the camera and splicing to replace an actor with what is obviously a mannequin. Most amazing about this picture (for its time) are its structure and the editing and camera techniques employed for its continuity. Panning and tilting wasn't new, but this movement of the camera in one scene to follow the action is exceptional for 1903. Likewise, Porter and others had already used the close-up. Porter employed an insert of a fire alarm in "Life of an American Fireman" and a privileged camera position for "The Gay Shoe Clerk." The shock value of the close-up in this film even serves form as its entirety is supposed to thrill.

Furthermore, the view from on top of the train is quite good. The transitioning between interior and exterior shots is fluent, and generally so is the continuation of action from scene to scene, with action exiting and entering scenes from appropriate directions. This is elementary film-making now, but in 1903, they were inventing it.

What I think is the most interesting part of "The Great Train Robbery," though, is its editing between the plot of the telegrapher and that of the robbers after their initial confrontation. After following the robbers for a while, the film cuts back to the "meanwhile" plot of the telegrapher. Initially, the barn dance scene doesn't appear to serve any narrative function--until the telegrapher enters to gather a posse. It's an interesting ordering of and transitioning between parallel actions. The plot isn't in temporal order, and it's a nice testament to Porter's innovation that a few modern viewers have been perplexed by how the posse catches up with the robbers so quickly.

It would take D.W. Griffith and others to build upon past work and their own in moving towards more entertaining and cinematic films, but the developments in narrative experimented with by pioneers like Porter paved the way.

(Note: This is one of four films that I've commented on because they're landmarks of early narrative development in film history. The others are "As Seen Through a Telescope," "Le Voyage dans la lune" and "Rescued by Rover.")

Throughout his film-making career, Porter was strongly influenced by contemporary British and French films, which he would have ready access to since the Edison Company regularly duped them. His "Uncle Josh at the Moving Picture Show" is a rip-off of Robert Paul's "The Countryman and the Cinematograph." "The Gay Shoe Clerk" is a revision of George Smith's "As Seen Through a Telescope." Porter also introduced intertitles to American cinema in "Uncle Tom's Cabin," having seen them in some of Smith's films. "Life of an American Fireman" reflects James Williamson's "Fire!" The temporal replay in that film was influenced by Georges Méliès's temporal replay of the Moon landing in "Le Voyage dans la lune." "Dream of a Rarebit Fiend" also owes plenty to Méliès.

"The Great Train Robbery" followed a recently created genre of crime and chase films begun in England. "The Daring Daylight Robbery" was especially of influence, as was, it is said by historians, a 1903 film called "The Robbery of the Mail Coach." "The Great Train Robbery" is also based on a play of the same title by Scott Marble. News of real train robberies also served as inspiration according to the Edison catalogue. Anyhow, with the exception of wholesale rip-offs, it's not discourageable that Porter learned from other films and adopted techniques and style from them for his own. He is worthy of history's praise for being such an avid student of film and one of the more active filmmakers of his time to develop film grammar.

Some film historians and critics say that Porter's work was uneven, that "The Grain Train Robbery" and perhaps one or two other films were a happenstance success, or fluke. Someone was bound to figure out the techniques of narrative as story films became more complex--confronting such problems as spatially separate actions and the continuity of action. I've seen a good share of Porter's work, however, and it's apparent that he was usually experimenting. He wasn't consistent like Méliès, which is good because his work becomes stale. Porter's previous experiments in editing resulted in this, his most accomplished story film and greatest success.

There are a few special effects in "The Great Train Robbery," as others have mentioned. It's nothing new: double-exposure matte work for the shot of the train outside the window and for the outside of the moving train's door, hand coloring, in addition to stopping the camera and splicing to replace an actor with what is obviously a mannequin. Most amazing about this picture (for its time) are its structure and the editing and camera techniques employed for its continuity. Panning and tilting wasn't new, but this movement of the camera in one scene to follow the action is exceptional for 1903. Likewise, Porter and others had already used the close-up. Porter employed an insert of a fire alarm in "Life of an American Fireman" and a privileged camera position for "The Gay Shoe Clerk." The shock value of the close-up in this film even serves form as its entirety is supposed to thrill.

Furthermore, the view from on top of the train is quite good. The transitioning between interior and exterior shots is fluent, and generally so is the continuation of action from scene to scene, with action exiting and entering scenes from appropriate directions. This is elementary film-making now, but in 1903, they were inventing it.

What I think is the most interesting part of "The Great Train Robbery," though, is its editing between the plot of the telegrapher and that of the robbers after their initial confrontation. After following the robbers for a while, the film cuts back to the "meanwhile" plot of the telegrapher. Initially, the barn dance scene doesn't appear to serve any narrative function--until the telegrapher enters to gather a posse. It's an interesting ordering of and transitioning between parallel actions. The plot isn't in temporal order, and it's a nice testament to Porter's innovation that a few modern viewers have been perplexed by how the posse catches up with the robbers so quickly.

It would take D.W. Griffith and others to build upon past work and their own in moving towards more entertaining and cinematic films, but the developments in narrative experimented with by pioneers like Porter paved the way.

(Note: This is one of four films that I've commented on because they're landmarks of early narrative development in film history. The others are "As Seen Through a Telescope," "Le Voyage dans la lune" and "Rescued by Rover.")

I enjoy this film even though it is very old and compared to today's cinema, very limited in its attempt at realism. But today's cinema would not be what it is without the original innovation of cinematic devices by Edwin S. Porter, one of films first masters. His progress in narrative construction and his work in special effects techniques astonished audiences like never before. His work was limited specifically because he used the static camera affecting the impact of each of his shots. His unique and influential editing style allowed the audience to take part in the action of the film, not sitting idly watching it. The movie is 12 minutes long and is considered the first narrative film in history. The most exciting scene is when the gangsters raid the train station and rob the train. The train is a really well done mat-shot of a train pulling into the station, frightening the audience in their seats. I personally am most excited by the final closing scene of the gangster shooting his gun, aiming it directly at the audience. This audience point of view shot makes me feel like the narrative of the train robbery enticed me to cheer for the Sheriff, and the angry gangster shoots at me because I was cheering for his enemy. This film and this sequence of the gangster shooting the audience was solidified in cinematic history when Martin Scorsese pays homage in 'Goodfellas', with Joe Pesci gun barrage and sinister look.

Arguably the first motion picture to employ the milieu of what would quickly become known as the Western genre, Edwin S. Porter's The Great Train Robbery was a smashing success with audiences (dozens of film history texts report with glee how viewers shrieked with fear and delight when a tightly-framed gunslinger pointed and fired directly at the camera) and made remarkable strides toward the establishment of longer, more narratively developed films. Porter's cutting was also among the most sophisticated to date, as multiple locations and events were suffused with a previously unseen urgency. Based on actual events, The Great Train Robbery ignited the imaginations of the scores who saw it -- making the movie one of the earliest examples of sensationalized, fictionalized screen adaptations taken from historical precedent.

Le saviez-vous

- AnecdotesThe original camera negative still exists in excellent condition. The Library of Congress, who holds it, can still make new prints.

- GaffesWhen the telegraph operator revives with his hands tied behind his back, he uses one of his hands to help him stand up and then quickly puts the hand behind his back again.

- Versions alternativesThere is an Italian edition of this film on DVD, distributed by DNA srl, "CENTRO! (Straight Shooting, 1917) + IL CAVALLO D'ACCIAIO (The Iron Horse, 1924) + LA GRANDE RAPINA AL TRENO (The Great Train Robbery, 1903)" (3 Films on a single DVD), re-edited with the contribution of film historian Riccardo Cusin. This version is also available for streaming on some platforms.

- ConnexionsEdited into Hollywood: The Dream Factory (1972)

Meilleurs choix

Connectez-vous pour évaluer et suivre la liste de favoris afin de recevoir des recommandations personnalisées

Détails

Box-office

- Budget

- 150 $US (estimé)

- Durée

- 11min

- Mixage

- Rapport de forme

- 1.33 : 1

Contribuer à cette page

Suggérer une modification ou ajouter du contenu manquant