ÉVALUATION IMDb

7,6/10

27 k

MA NOTE

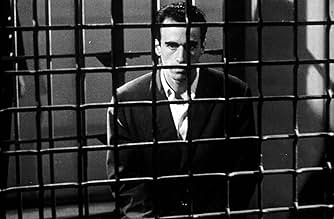

Michel est libéré de prison après avoir purgé une peine pour vol. Sa mère meurt et il a recours au vol à la tire pour survivre.Michel est libéré de prison après avoir purgé une peine pour vol. Sa mère meurt et il a recours au vol à la tire pour survivre.Michel est libéré de prison après avoir purgé une peine pour vol. Sa mère meurt et il a recours au vol à la tire pour survivre.

- Prix

- 3 nominations au total

Avis en vedette

This slow burn film from Robert Bresson is not going to be to everyone's taste, and I'm not sure it was to mine. It's a film I admired more than enjoyed.

It tells the story of a man who's addicted to theft, or maybe more accurately addicted to the rush of getting away with theft, or maybe more accurately addicted to the rush of possibly being caught thieving. It's not a long movie but it may try your patience, as it's very slow and very quiet. The main character is a bit of a blank slate, and he remains so. We never learn much about him, and I personally didn't feel especially invested in what happened to him. It was only in reading about the film after seeing it that I found out the ending is considered to be remarkable among film scholars, but I didn't react to it much myself.

The best scenes in the movie are those that show the elaborate rituals that exist among pickpocket teams, and the pretty amazing feats they pull off. They're like magicians who use sleight of hand for nefarious purposes.

Grade: B+

It tells the story of a man who's addicted to theft, or maybe more accurately addicted to the rush of getting away with theft, or maybe more accurately addicted to the rush of possibly being caught thieving. It's not a long movie but it may try your patience, as it's very slow and very quiet. The main character is a bit of a blank slate, and he remains so. We never learn much about him, and I personally didn't feel especially invested in what happened to him. It was only in reading about the film after seeing it that I found out the ending is considered to be remarkable among film scholars, but I didn't react to it much myself.

The best scenes in the movie are those that show the elaborate rituals that exist among pickpocket teams, and the pretty amazing feats they pull off. They're like magicians who use sleight of hand for nefarious purposes.

Grade: B+

A remarkable film even though the ending is anti-climactic. An amateur pickpocket gets lucky and meets Kassagi, the real-life pickpocket who served as the film's technical consultant. The most amazing scene is the one where three pickpockets rob one passenger after another on a train, taking wallets, passing them off to each other, then emptying and dumping them (or in one case, neatly replacing the lightened wallet in a man's pocket!). The light-finger techniques seem more or less authentic, although I imagine the director's script might have called for inauthentic bits of business. (No, I am not a pickpocket; I was a mark once, and they really messed up my life for a couple of days, but I have been fascinated ever since.)

The pickpockets in this movie follow the European style of stealing men's wallets practically face-to-face. (American pickpockets traditionally prefer to steal from behind to avoid any chance of a mark seeing their faces. When I was taken, I never saw, heard or felt anything.)

LaSalle as Michel is deadpan, but that seems to be part of his character. Now and again, he bubbles a little with suppressed feeling, mostly anger. His passion for Jeanne (Marika Green) is so completely submerged that it does not come out until the end. (If you think I'm spoiling anything, you will want to skip the on screen legend that opens the film because it gives away even more.) As a love story, this does not work. I get it, though: Something happened before the film begins that makes Michel extremely ashamed. He can't be with his mother or anyone he cares about because of his guilt.

The pickpockets in this movie follow the European style of stealing men's wallets practically face-to-face. (American pickpockets traditionally prefer to steal from behind to avoid any chance of a mark seeing their faces. When I was taken, I never saw, heard or felt anything.)

LaSalle as Michel is deadpan, but that seems to be part of his character. Now and again, he bubbles a little with suppressed feeling, mostly anger. His passion for Jeanne (Marika Green) is so completely submerged that it does not come out until the end. (If you think I'm spoiling anything, you will want to skip the on screen legend that opens the film because it gives away even more.) As a love story, this does not work. I get it, though: Something happened before the film begins that makes Michel extremely ashamed. He can't be with his mother or anyone he cares about because of his guilt.

More interesting than any individual film, it's Bresson's philosophy that I feel is worth examining. He's all about striving, the question is what for? If it's purity, as most would agree, and purity always seems like something to aspire to, is it a purity that we can take as a base for living?

I don't think I will have conclusions before Balthazar, perhaps his most famous. Already, since Diary of a Priest, I can see him moving in a direction, growing that philosophy. Even more sparse, even more laconic, removes flourish and leaves bare floors so that we endure something being revealed in the pacing. That's fine. More revealing is another trajectory being delineated, human- based.

It's once more about a lone youth who struggles with a life that suffocates. In Diary he was a pious young priest who wanted absolute sincerity in the face of life; but people were complicated beings, the journey caused spiritual torment, questions of angst abounded. In Man Escaped the same youth becomes a prisoner, also endures a life of anguish, but now endures quietly, without torment and piety. It was Bresson peeling away the romanticizing of suffering of Diary, what was left was simply the work of breaking free from that prison- world, stoicism in place of romanticism.

So what does he do in this next one? The same youth once more, but now he's not bound by duty to truth or has any work set out before him. Now he's free to wander the world which the man in Escaped had struggled to break free to. Without an intellectual or other struggle before him, he's simply awash with time. He's stifled by the freedom, he has no place. He perceives himself as a man of lofty talents, possibly a genius, but wastes these talents in being a pickpocket around town who won't even go see his dying mother. He always comes and goes from his tiny apartment to no real purpose.

Observant viewers will note the equation of pickpocketing as presented in the film, an elaborately precise choreography of hands and motions, with Bresson's own filmmaking. Film lore touts him as pure and simple as if that simplicity is conquered without effort, in truth he's all about the meticulous timing and moving of exact pieces. His favorite tool is exactly this game of hide and show that controls what we see; for example a scene like in Man Escaped where the new cellmate is introduced off-camera, we don't know who our man is talking to until we turn to see. He does it here too, often by having characters turn and leave, questions hanging, creating gap and resonance. He's the opposite of natural.

Back to the conundrum expressed at the beginning however; if this is pure, what does it strive purely for?

The only answer I get here is that we no longer have a man who is trying to understand life, or someone who works towards an end, these selves have been shed. Now we have someone who endures, but has no idea exactly what or what for. It's Bresson inching towards the same cessation that he strives for visually. What stands before him now is what he sketches in the opening intertitle; something pushes the man from the inside.

He bangles this all up at the end, and I believe that looking back he would probably have been unsatisfied himself. He reverts back to his romanticism where the tormented young man has love reserved for him, but a wistful love that doesn't feel earned, there's simply nothing that rings true about her infatuation with him. This is Eva Green's aunt by the by.

So this has done its job, shed one self and one set of conundrums and replaced them with another. Onwards to his next, which looks like another draft of the same philosophy, and then Balthazar is around the corner. I already believe I disagree with Schrader.

I don't think I will have conclusions before Balthazar, perhaps his most famous. Already, since Diary of a Priest, I can see him moving in a direction, growing that philosophy. Even more sparse, even more laconic, removes flourish and leaves bare floors so that we endure something being revealed in the pacing. That's fine. More revealing is another trajectory being delineated, human- based.

It's once more about a lone youth who struggles with a life that suffocates. In Diary he was a pious young priest who wanted absolute sincerity in the face of life; but people were complicated beings, the journey caused spiritual torment, questions of angst abounded. In Man Escaped the same youth becomes a prisoner, also endures a life of anguish, but now endures quietly, without torment and piety. It was Bresson peeling away the romanticizing of suffering of Diary, what was left was simply the work of breaking free from that prison- world, stoicism in place of romanticism.

So what does he do in this next one? The same youth once more, but now he's not bound by duty to truth or has any work set out before him. Now he's free to wander the world which the man in Escaped had struggled to break free to. Without an intellectual or other struggle before him, he's simply awash with time. He's stifled by the freedom, he has no place. He perceives himself as a man of lofty talents, possibly a genius, but wastes these talents in being a pickpocket around town who won't even go see his dying mother. He always comes and goes from his tiny apartment to no real purpose.

Observant viewers will note the equation of pickpocketing as presented in the film, an elaborately precise choreography of hands and motions, with Bresson's own filmmaking. Film lore touts him as pure and simple as if that simplicity is conquered without effort, in truth he's all about the meticulous timing and moving of exact pieces. His favorite tool is exactly this game of hide and show that controls what we see; for example a scene like in Man Escaped where the new cellmate is introduced off-camera, we don't know who our man is talking to until we turn to see. He does it here too, often by having characters turn and leave, questions hanging, creating gap and resonance. He's the opposite of natural.

Back to the conundrum expressed at the beginning however; if this is pure, what does it strive purely for?

The only answer I get here is that we no longer have a man who is trying to understand life, or someone who works towards an end, these selves have been shed. Now we have someone who endures, but has no idea exactly what or what for. It's Bresson inching towards the same cessation that he strives for visually. What stands before him now is what he sketches in the opening intertitle; something pushes the man from the inside.

He bangles this all up at the end, and I believe that looking back he would probably have been unsatisfied himself. He reverts back to his romanticism where the tormented young man has love reserved for him, but a wistful love that doesn't feel earned, there's simply nothing that rings true about her infatuation with him. This is Eva Green's aunt by the by.

So this has done its job, shed one self and one set of conundrums and replaced them with another. Onwards to his next, which looks like another draft of the same philosophy, and then Balthazar is around the corner. I already believe I disagree with Schrader.

To my previous comments, I should like to add/correct. When I said that Kassagi, who plays "first accomplice" (1er complice), was a 'real-life pickpocket who served as the film's technical consultant' I was not only inaccurate, but the fact that Kassagi was actually a stage magician has some bearing on the film itself, for although the scene in which the pickpockets rip off a series of train passengers is authentic in that it shows how pickpockets operate in terms of teamwork and speed, nevertheless, the moment when Kassagi (?) 'neatly replac[es] the lightened wallet [back] in a man's pocket' is not something a real pickpocket would likely do; it is, however, exactly what a stage magician would do. A real pickpocket has no audience (or so he hopes) whereas a magician wants the audience to see him make a monkey of the hapless "volunteer from the audience." In this case, Kassagi's idea (as I am sure it was) provides a brief moment of comic relief in the middle of a movie that is otherwise without a lot of humor. It is a welcome touch and Bresson was wise to keep it in. Now, I also engaged in a fallacy when I said that 'American pickpockets traditionally prefer to steal from behind to avoid any chance of a mark seeing their faces.' In reality, American pickpockets take from behind because of necessity: even by 1959 when 'Pickpocket" was released, American men more and more carried their wallets in the hip pocket whereas European men, as can be seen in this film, continued to use the inside breast pocket. While the business about seeing the mark's face is part of the lore of American petty criminals, it is not the cause of the American style of picking pockets, but rather a rationalization after the fact.

In his dismissal determination to keep out elements often thought fundamental to the mediumspectacle, drama, performance Bresson has followed an incomparable personal vision of the world that stays consistent whatever the nature of his subject matter...

In "Pickpocket," a petty thief understands life's mystery only when his conventional wisdom is violently shaken and embraces humanity through his newfound love Most notable, however, is not the emphasis upon redemption attained through communication and self-sacrifice, but the high-purity of Bresson's style...

The camera keeps out pictorial beauty to create an abstract timeless world through the detached, detailed observation of hands, faces, and objects; natural sounds rather than music to satisfy the need In thus rejecting conventional realism and characterization, Bresson manifested a fascination not with human psychology but with the capacity of the soul to survive in a world of pain, disbelieve, and restriction...

In "Pickpocket," a petty thief understands life's mystery only when his conventional wisdom is violently shaken and embraces humanity through his newfound love Most notable, however, is not the emphasis upon redemption attained through communication and self-sacrifice, but the high-purity of Bresson's style...

The camera keeps out pictorial beauty to create an abstract timeless world through the detached, detailed observation of hands, faces, and objects; natural sounds rather than music to satisfy the need In thus rejecting conventional realism and characterization, Bresson manifested a fascination not with human psychology but with the capacity of the soul to survive in a world of pain, disbelieve, and restriction...

Le saviez-vous

- AnecdotesBanned in Finland until 1965 because of its depiction of authentic pickpocketing techniques.

- ConnexionsEdited into Histoire(s) du cinéma: Une histoire seule (1989)

- Bandes originalesSuite de symphonies d'Amadis (selection)

(uncredited)

Music by Jean-Baptiste Lully (as J.B. Lulli)

Éditions Transatlantiques

Meilleurs choix

Connectez-vous pour évaluer et surveiller les recommandations personnalisées

- How long is Pickpocket?Propulsé par Alexa

Détails

Box-office

- Brut – à l'échelle mondiale

- 7 541 $ US

- Durée1 heure 16 minutes

- Couleur

- Rapport de forme

- 1.37 : 1

Contribuer à cette page

Suggérer une modification ou ajouter du contenu manquant

Lacune principale

By what name was Pickpocket (1959) officially released in India in English?

Répondre