CALIFICACIÓN DE IMDb

6.9/10

5.4 k

TU CALIFICACIÓN

Agrega una trama en tu idiomaA police officer refuses to arrest a young man for offering drugs to his friends.A police officer refuses to arrest a young man for offering drugs to his friends.A police officer refuses to arrest a young man for offering drugs to his friends.

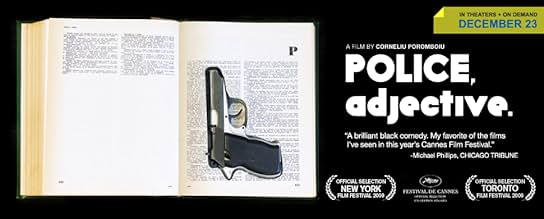

- Premios

- 15 premios ganados y 15 nominaciones en total

George Remes

- Vali

- (as Remes George)

Constantin Dita

- Officer on Duty

- (as Costi Dita)

- Dirección

- Guionista

- Todo el elenco y el equipo

- Producción, taquilla y más en IMDbPro

Opiniones destacadas

One of the best movies of the year - and, definitely, of the Romanian cinema all over.

After "12:08: East of Bucharest" (aka "A fost sau n-a fost" - original title), Cornel Porumboiu does it again: an incisive and tender, empathic and ruthless look into our contemporary humanity. It brings back memories of Kafka's "Trial": the blind mechanism of Law, meant to help us live better and, because of so many machine-like people, turned into a device for destroying lives. In the role of the young policeman who loses his faith into the system, Dragos Bucur brings on screen another of his memorable performances - subtle, deep, finely tuned.

But the main virtue of this excellent movie, of course, is Cornel's directing - credible, original, precise. The static long shots, creating pent-up inner tensions... the unbearable waiting scenes, under a leaden sky... the discrete plastic compositions of the frame... the insidious rhythm... the careful attention to the minutest details - everything, with a due meaning and a perfectly weighted impact.

Special kudos for the pivotal scene built up around Mirabela Dauer's song "I Don't Leave You Love" - a rare piece of abstruse idiocy, used as a main axis for the protagonist's confrontation with the life's absolute absurdity. The scene is so masterfully built and shot, that it makes us scream laughing (in Cannes, the audience was delirious) - but the ultimate meaning is tragic... this being Porumboiu's definitory characteristic - as he said himself: "comical authors are often the saddest ones of all".

After "12:08: East of Bucharest" (aka "A fost sau n-a fost" - original title), Cornel Porumboiu does it again: an incisive and tender, empathic and ruthless look into our contemporary humanity. It brings back memories of Kafka's "Trial": the blind mechanism of Law, meant to help us live better and, because of so many machine-like people, turned into a device for destroying lives. In the role of the young policeman who loses his faith into the system, Dragos Bucur brings on screen another of his memorable performances - subtle, deep, finely tuned.

But the main virtue of this excellent movie, of course, is Cornel's directing - credible, original, precise. The static long shots, creating pent-up inner tensions... the unbearable waiting scenes, under a leaden sky... the discrete plastic compositions of the frame... the insidious rhythm... the careful attention to the minutest details - everything, with a due meaning and a perfectly weighted impact.

Special kudos for the pivotal scene built up around Mirabela Dauer's song "I Don't Leave You Love" - a rare piece of abstruse idiocy, used as a main axis for the protagonist's confrontation with the life's absolute absurdity. The scene is so masterfully built and shot, that it makes us scream laughing (in Cannes, the audience was delirious) - but the ultimate meaning is tragic... this being Porumboiu's definitory characteristic - as he said himself: "comical authors are often the saddest ones of all".

This is a film about a policeman and a matter of conscience. There's a circle of three friends, two boys and a girl, one boy has denounced the other boy to the police for supplying marijuana, it appears that this is so he can have the girl to himself. Our policeman, Cristi is being pressed to slap the cuffs on the kid by his superior, the charge is a life-wrecker, seven years in prison for smoking joints at lunch break. Cristi spends the movie trying to avoid this outcome. As he says, it's a foolish law.

Cristi is pushing against a bureaucracy that simply doesn't care, and ends up looking like a fool when he talks to people who are more educated with him, for example suffering his girlfriend's overanalysis of a ludicrous ballad, or the pseudo-dialectics of his boss, a masterpiece of sophistry. The point is that language or words often constitute another form of aggression, as the Athenians knew, you can win any argument once you have mastered rhetoric. Of course, as soon as anyone raises their voice or gets upset, this is taken as a sign that they've lost the argument, the intellectual warfare, losing having nothing whatsoever to do with being right or wrong of course.

The film is about conscience, something that totalitarian societies tried to eliminate in favour of the wisdom of the law. Good film although some of the intricacies of the discussions were lost on me not being a Romanian, and unable to follow the thread of Romanian spelling and grammar.

I actually loved the movie on an aesthetic level, I doubt it was intentional, but I always pick up on dashes of yellow in visual arts, an eccentricity of mine. For example in the street where the kid under surveillance lives, all the utilities pipes that come out onto the street are painted bright yellow, the young girl appears first wearing a bright yellow top under denim, and Cristi uses a yellow lighter and a yellow pen, most of the rest of the colour in the movie is very dull and subdued, I enjoyed these flashes. It's also nice seeing old communist offices, nowadays in the west everything is open plan and new, no-one has offices except the capo di tutti capi. Here there's peeling plaster, old caved in lockers, and a little peace and quiet. Hell I even liked just seeing Cristi sat down eating. Then there's the formal way where letters and plans are just shown on the screen with no background. I like the style of the police reports.

I would just point out that based on my understanding of the film, the English title is a mistranslation, politist is like the French word policier, which all we can translate as is "police procedural"; another translation is "policeman". The translations are nouns though so I was a little confused as to why it's being referred to as an adjective. Maybe the error is meaningful?

Cristi is pushing against a bureaucracy that simply doesn't care, and ends up looking like a fool when he talks to people who are more educated with him, for example suffering his girlfriend's overanalysis of a ludicrous ballad, or the pseudo-dialectics of his boss, a masterpiece of sophistry. The point is that language or words often constitute another form of aggression, as the Athenians knew, you can win any argument once you have mastered rhetoric. Of course, as soon as anyone raises their voice or gets upset, this is taken as a sign that they've lost the argument, the intellectual warfare, losing having nothing whatsoever to do with being right or wrong of course.

The film is about conscience, something that totalitarian societies tried to eliminate in favour of the wisdom of the law. Good film although some of the intricacies of the discussions were lost on me not being a Romanian, and unable to follow the thread of Romanian spelling and grammar.

I actually loved the movie on an aesthetic level, I doubt it was intentional, but I always pick up on dashes of yellow in visual arts, an eccentricity of mine. For example in the street where the kid under surveillance lives, all the utilities pipes that come out onto the street are painted bright yellow, the young girl appears first wearing a bright yellow top under denim, and Cristi uses a yellow lighter and a yellow pen, most of the rest of the colour in the movie is very dull and subdued, I enjoyed these flashes. It's also nice seeing old communist offices, nowadays in the west everything is open plan and new, no-one has offices except the capo di tutti capi. Here there's peeling plaster, old caved in lockers, and a little peace and quiet. Hell I even liked just seeing Cristi sat down eating. Then there's the formal way where letters and plans are just shown on the screen with no background. I like the style of the police reports.

I would just point out that based on my understanding of the film, the English title is a mistranslation, politist is like the French word policier, which all we can translate as is "police procedural"; another translation is "policeman". The translations are nouns though so I was a little confused as to why it's being referred to as an adjective. Maybe the error is meaningful?

Police, Adjective This is an absolutely brilliant film. Many films have been made in Germany or the Czech Republic or Spain or various Latin American countries, and so on and on, about periods of interregnum between one form of government and another. Writer/Director Porumboiu goes right to the details in Romania. He takes the smallest possible case, an undercover officer checking out a high-school drug dealer, and makes us wonder about the biggest metaphysical situations involving law and justice. Wisely—almost incredibly—Porumboiu sets aside macropolitics and doesn't make a partisan or political film. Instead, he forces us to imagine the links between private behaviour and philosophical concepts.

Many people are constantly writing that the movie is too slow or too long. Hell, I say that about car-chase movies that are 90 mins. of explosions or 130 mins. of James Cameron's computer-animation teams. There is not one wasted second in this film. It is not indulgent in the slightest. There are no car chases. This is a movie about a narc tailing a high-school kid. That's what it is. The only time the movie really really drags is when Cristi, the narc/undercover guy, is watching the home of the alleged squealer. That does go on for a long time, but, structurally, it makes sense, and Porumboiu leavens it a bit by making Cristi get tea from a nearby shop and discuss what he's doing in a communist-realist way that chips in to the overall narrative.

The way Porumboiu binds the film together is admirable—we see Cristi early on telling his overweight colleague that that colleague just can't play soccer with them—those are the rules. Then Cristi gets told by the prosecutor that he isn't entitled to comment on laws. And then there's Cristi's girlfriend (the rules of language), and Zelu (sees all laws, accepts none, really) and Cristi's boss, Angelache (the rules of law, expressed by language).

The endless opening and closing of doors, the bureaucracy, the people who think their lives are so much more important than yours, is compelling. Cristi never really imposes. He just has a sense of what is right (and he is a policing figure). His overweight colleague puts upon him. His lazy (political but useless) colleague Zelu is of no help. He goes to the prosecutor (Marian Ghenea—in a truly wonderful performance) and is granted a promise that we later learn has probably been betrayed. Costi, Vali, Doina—all are unwilling to act, knowingly or unknowingly, towards justice. Part of what made The Death of Mr Lazarescu by Puiu so compelling was precisely the fact that one knew that, whether or not you had the greatest American health insurance in the world (or even the most money in the world, maybe), or you lived in a country with one of the greatest public health insurance programs there were, you still were not immune to basic human failings. If Puiu did that with health care and medicine, Porumboiu does that with law and justice and society. What Poromboiu shows us, relentlessly, is that our lives are contingent upon others, and if others treat us the way we treat them, well. . . .

There just isn't a bad performance in this film. One would finally have to say that Dragos Bucur is effective in his impossible role. He is the hunched anti-hero post-communist but still communist narc. His girlfriend, Anca, can talk of anaphoras, but when he tries to express what he knows is right, the state, in the person of well-known Vlad Ivanov, gets Cristi out a dictionary from which he cannot escape. Dictionaries, after all, like language, are arbitrary documents. A "tree" in Brazil means something entirely different from a "tree" in Siberia. Language is arbitrary and contextual, and this sophisticated film works with this knowledge.

This is a carefully filmed movie that rarely draws attention to itself. As far as I can tell, every time Cristi is shadowing someone, the effect is very authentic. There are a lot of long shots. Close shots are sparing. Office shots are always as they should be or oblique. When Cristi gets back to his flat, the way Porumboiu films it so that we could only ever see the hallway and never a bedroom or any kind of intimacy at all is very, very wisely done. In some respects, Porumboiu boldly refuses to answer American hopes. He gives us no cheesy intimacy, and keep us always focused on Cristi, the man outside—outside shadowing a kid who may be a drug dealer, outside the changing Romanian legal system, outside his girlfriend's perfect—but changeable—command of language. Maybe Anca is the one who really ought to be determining things, for images are symbols, and symbols are images.

As for the climactic scene, 20 mins. of pure dictionary: I can't think of 20 other minutes I'd love to watch more, from _The Getaway_ to _Unforgiven_. The climax of _Police, Adjective_ is utterly riveting, if you've grasped what has gone on before.

This is just an all-around great movie. At times, you can sense opportunities for indulgence, but Porumboiu never takes them. I hope he'll continue not to.

Yes, it's a given that people not from the U.S. may not understand movies from other places. But I'm getting a little bit tired of this. I can watch movies from Korea or Argentina or just about any country in the world and enjoy them and understand them and feel my way into them and engage with them intellectually and emotionally.

Police, Adjective is definitely going to go down as a very important film. It comprises the human and the metaphysical the while excising the obvious political. That makes it political. This is an important film. Negative reviewers desperately cling to seeing "police" as a noun, and that is not what this film is about. ww

Many people are constantly writing that the movie is too slow or too long. Hell, I say that about car-chase movies that are 90 mins. of explosions or 130 mins. of James Cameron's computer-animation teams. There is not one wasted second in this film. It is not indulgent in the slightest. There are no car chases. This is a movie about a narc tailing a high-school kid. That's what it is. The only time the movie really really drags is when Cristi, the narc/undercover guy, is watching the home of the alleged squealer. That does go on for a long time, but, structurally, it makes sense, and Porumboiu leavens it a bit by making Cristi get tea from a nearby shop and discuss what he's doing in a communist-realist way that chips in to the overall narrative.

The way Porumboiu binds the film together is admirable—we see Cristi early on telling his overweight colleague that that colleague just can't play soccer with them—those are the rules. Then Cristi gets told by the prosecutor that he isn't entitled to comment on laws. And then there's Cristi's girlfriend (the rules of language), and Zelu (sees all laws, accepts none, really) and Cristi's boss, Angelache (the rules of law, expressed by language).

The endless opening and closing of doors, the bureaucracy, the people who think their lives are so much more important than yours, is compelling. Cristi never really imposes. He just has a sense of what is right (and he is a policing figure). His overweight colleague puts upon him. His lazy (political but useless) colleague Zelu is of no help. He goes to the prosecutor (Marian Ghenea—in a truly wonderful performance) and is granted a promise that we later learn has probably been betrayed. Costi, Vali, Doina—all are unwilling to act, knowingly or unknowingly, towards justice. Part of what made The Death of Mr Lazarescu by Puiu so compelling was precisely the fact that one knew that, whether or not you had the greatest American health insurance in the world (or even the most money in the world, maybe), or you lived in a country with one of the greatest public health insurance programs there were, you still were not immune to basic human failings. If Puiu did that with health care and medicine, Porumboiu does that with law and justice and society. What Poromboiu shows us, relentlessly, is that our lives are contingent upon others, and if others treat us the way we treat them, well. . . .

There just isn't a bad performance in this film. One would finally have to say that Dragos Bucur is effective in his impossible role. He is the hunched anti-hero post-communist but still communist narc. His girlfriend, Anca, can talk of anaphoras, but when he tries to express what he knows is right, the state, in the person of well-known Vlad Ivanov, gets Cristi out a dictionary from which he cannot escape. Dictionaries, after all, like language, are arbitrary documents. A "tree" in Brazil means something entirely different from a "tree" in Siberia. Language is arbitrary and contextual, and this sophisticated film works with this knowledge.

This is a carefully filmed movie that rarely draws attention to itself. As far as I can tell, every time Cristi is shadowing someone, the effect is very authentic. There are a lot of long shots. Close shots are sparing. Office shots are always as they should be or oblique. When Cristi gets back to his flat, the way Porumboiu films it so that we could only ever see the hallway and never a bedroom or any kind of intimacy at all is very, very wisely done. In some respects, Porumboiu boldly refuses to answer American hopes. He gives us no cheesy intimacy, and keep us always focused on Cristi, the man outside—outside shadowing a kid who may be a drug dealer, outside the changing Romanian legal system, outside his girlfriend's perfect—but changeable—command of language. Maybe Anca is the one who really ought to be determining things, for images are symbols, and symbols are images.

As for the climactic scene, 20 mins. of pure dictionary: I can't think of 20 other minutes I'd love to watch more, from _The Getaway_ to _Unforgiven_. The climax of _Police, Adjective_ is utterly riveting, if you've grasped what has gone on before.

This is just an all-around great movie. At times, you can sense opportunities for indulgence, but Porumboiu never takes them. I hope he'll continue not to.

Yes, it's a given that people not from the U.S. may not understand movies from other places. But I'm getting a little bit tired of this. I can watch movies from Korea or Argentina or just about any country in the world and enjoy them and understand them and feel my way into them and engage with them intellectually and emotionally.

Police, Adjective is definitely going to go down as a very important film. It comprises the human and the metaphysical the while excising the obvious political. That makes it political. This is an important film. Negative reviewers desperately cling to seeing "police" as a noun, and that is not what this film is about. ww

The Romanian film wonder goes on and what's wonderous about it is that it's not afraid of life, like most movies around the world are. Since the beginning of the 1900s, there's an agreement about that life being absolutely boring. Lucky thing you can cut the film.

But here, we follow the young policeman on a routine mission, trying to investigate a supposed drug crime. The camera goes on for ten minutes, nothing happens or more likely...everything happens. What's morality about. Following the law or following your conscience? Or is it the same thing? Or should it be? An action drama there the action takes place inside the characters and the viewers. And that's absolutely fair enough.

But here, we follow the young policeman on a routine mission, trying to investigate a supposed drug crime. The camera goes on for ten minutes, nothing happens or more likely...everything happens. What's morality about. Following the law or following your conscience? Or is it the same thing? Or should it be? An action drama there the action takes place inside the characters and the viewers. And that's absolutely fair enough.

I first watched this film about a year ago, and I struggled through it because it truly is one of the slowest and uneventful films you'll ever see, but It has grown on me a lot and isn't a film that you'll forget after seeing. The film deals with themes like guilt, responsibility, choice, patience, with some underlined political themes. Its one thing to conceptualize a film effectively but it's another to execute it correctly, and I think Corneliu Porumboiu did a very honorable job in both those departments. It's one of my favorite films, actually. there's a scene near the end of the film where the main character, one of his colleagues, and his boss are sitting in his office discussing the main character's struggle between the law and his own conscience. This scene goes on for close to 30 minutes if i remember correctly, and it's all done on one shot, with the exception of a few little overlapping shots to view the contents of a dictionary in the main character's hands. I was really impressed by that whole scene. Even if you don't love it, it's definitely worth at least one watch.

¿Sabías que…?

- TriviaRomania's official submission to 82nd Academy Award's Foreign Language in 2010.

- Bandas sonorasNu te parasesc iubire

Performed by Mirabela Dauer

Arranged by Dan Dimitriu

Lyrics by Dan Ioan Pantoiu

Produced by Roton Music

Played and discussed at Cristi's home

Selecciones populares

Inicia sesión para calificar y agrega a la lista de videos para obtener recomendaciones personalizadas

- How long is Police, Adjective?Con tecnología de Alexa

Detalles

Taquilla

- Presupuesto

- EUR 800,000 (estimado)

- Total en EE. UU. y Canadá

- USD 53,206

- Fin de semana de estreno en EE. UU. y Canadá

- USD 19,452

- 27 dic 2009

- Total a nivel mundial

- USD 162,974

- Tiempo de ejecución1 hora 55 minutos

- Color

- Mezcla de sonido

- Relación de aspecto

- 1.85 : 1

Contribuir a esta página

Sugiere una edición o agrega el contenido que falta

Principales brechas de datos

By what name was Politist, adjectiv (2009) officially released in India in English?

Responda