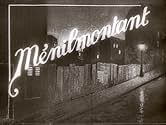

Ménilmontant

- 1926

- 38min

CALIFICACIÓN DE IMDb

7.8/10

2.9 k

TU CALIFICACIÓN

Agrega una trama en tu idiomaA couple is brutally murdered in the working-class district of Paris. Later on, the narrative follows the lives of their two daughters, both in love with a Parisian thug and leading them to ... Leer todoA couple is brutally murdered in the working-class district of Paris. Later on, the narrative follows the lives of their two daughters, both in love with a Parisian thug and leading them to separate ways.A couple is brutally murdered in the working-class district of Paris. Later on, the narrative follows the lives of their two daughters, both in love with a Parisian thug and leading them to separate ways.

- Dirección

- Guionista

- Elenco

- Dirección

- Guionista

- Todo el elenco y el equipo

- Producción, taquilla y más en IMDbPro

Opiniones destacadas

There is an old German proverb that says that size doesn't matter ( well, size does count for this count having in mind the perimeter of his Teutonic heiresses

) and the saying rings true with "Ménilmontant" a medium-length silent film directed by Herr Dimitri Kirsanoff, and a striking, disturbing masterpiece.

Herr Kirsanoff's direction is astonishing in every aspect of the film, particularly in its technique. It's a mixture of drama, avant-garde, experimental film and hyper realism. The story depicted in the film ( the terrible life of two orphan sisters ) doesn't allow any concession to the audience; to watch "Ménilmontant" today still invokes amazement, distress and an infinite sadness.

From the very start of the film ( superb, striking and masterful editing by Herr Kirsanoff himself ) the director shows power and imagination and a strong control of film narrative ( there is no need of intertitles ). Kiransoff's use of imagery is thrilling and brilliant. Images emphasize a ruined happy childhood and the duality and dangers of a big city ( flashbacks, imaginative camera angles, dreamy and poetic shots ) not to mention the sorrowful life of the two orphans, an existence of loneliness, abandonment and despair that broke the heart of a heartless German aristocrat, especially the superb scene in which the younger sister ( touching Dame Nadia Sibirskaia ) ,alone and hungry on a bench park with her baby, accepts some bread from an old man, a moving and lyrical scene, that summarizes the spirit and achievement of this oeuvre.

"Ménilmontant" is a work of art, a striking experimental style in the service of a tragic and sad story, brilliantly and disturbingly balanced.

And now, if you'll allow me, I must temporarily take my leave because this German Count must become a little livelier.

Herr Graf Ferdinand Von Galitzien http://ferdinandvongalitzien.blogspot.com/

Herr Kirsanoff's direction is astonishing in every aspect of the film, particularly in its technique. It's a mixture of drama, avant-garde, experimental film and hyper realism. The story depicted in the film ( the terrible life of two orphan sisters ) doesn't allow any concession to the audience; to watch "Ménilmontant" today still invokes amazement, distress and an infinite sadness.

From the very start of the film ( superb, striking and masterful editing by Herr Kirsanoff himself ) the director shows power and imagination and a strong control of film narrative ( there is no need of intertitles ). Kiransoff's use of imagery is thrilling and brilliant. Images emphasize a ruined happy childhood and the duality and dangers of a big city ( flashbacks, imaginative camera angles, dreamy and poetic shots ) not to mention the sorrowful life of the two orphans, an existence of loneliness, abandonment and despair that broke the heart of a heartless German aristocrat, especially the superb scene in which the younger sister ( touching Dame Nadia Sibirskaia ) ,alone and hungry on a bench park with her baby, accepts some bread from an old man, a moving and lyrical scene, that summarizes the spirit and achievement of this oeuvre.

"Ménilmontant" is a work of art, a striking experimental style in the service of a tragic and sad story, brilliantly and disturbingly balanced.

And now, if you'll allow me, I must temporarily take my leave because this German Count must become a little livelier.

Herr Graf Ferdinand Von Galitzien http://ferdinandvongalitzien.blogspot.com/

Dimitri Kirsanoff, born in Estonia but operating mostly in Paris, was heavily influenced by the theories of Soviet Montage. In his most famous short film, 'Ménilmontant (1926)' still frightfully obscure in most circles he adheres to this style strictly, almost obsessively. His preference towards a brisk editing pace carries a unique vitality that is also seen in the work of Soviet masters Eisenstein and Vertov, who pioneered and perfected the technique of montage in the mid-to-late 1920s. But, nevertheless, I don't think it works quite as well here. 'The Battleship Potemkin (1925)' and 'The Man with the Movie Camera (1929) perhaps the two most recognised works of Soviet montage utilise their chosen editing style to full effect precisely because they place greater emphasis on the collective over the individual, in accordance with traditional Communist ideology. There is deliberately no emotional connection attempted nor made between the viewer and any individual movie character, for that would be contrary to the filmmaker's intentions (interestingly, however, the montage fell out of preference from the 1930s in favour of Soviet realism).

'Ménilmontant' falters because it strives to create an emotional connection with the characters (particularly the younger sister, played by Nadia Sibirskaïa), but Kirsanoff's chosen editing style continually keeps the audience at an arm's length. The closest he comes to true pathos is with the park-bench sequence, when an old man offers some bread and meat to the famished woman, delicately avoiding eye contact to preserve her dignity. Even in this scene, the montage style intrudes. A director like Chaplin (and I'm a romantic at heart, so he's naturally one of favourite filmmakers) would have placed the camera at a distance, framing the profiles of both the woman and the old man within the same shot, thus capturing the subtle emotions and inflections of both parties simultaneously. Kirsanoff somewhat confuses the scene, cutting sequentially between the woman, the man and the food in a manner that reduces a simple, poignant act of kindness into a technical exercise in film editing. It works adequately, of course, a precise demonstration of the Kuleshov Effect, but there's relatively little heart in it.

But we'll cease with my complaints hereafter. I know my own film tastes well enough to recognise that what I disliked about the film its emotional distance, for example represents precisely what others love about it. There's no doubting that the photography (when it's kept on screen long enough) is breathtakingly spectacular, making accomplished use of lighting, shadows and in-camera optical effects such as dissolves, irises and superimpositions. There are touches of the surreal. Kirsanoff cuts non-discriminately forwards in time, backwards and into his characters' dreams, fragmenting time and reality into a series of shattered images, their individual meanings obscure until considered sequentially as in the pieces of a puzzle. Most impressive, I thought, was how several shots captured the linear perspective of roads and alleys, watching his characters gradually depart into the distance as though merely following the predetermined pathways of their future. The film ends exactly as it begins with a bloody and unexplained murder suggesting the inevitable cycle of human suffering, its causes unknown and forever incomprehensible.

'Ménilmontant' falters because it strives to create an emotional connection with the characters (particularly the younger sister, played by Nadia Sibirskaïa), but Kirsanoff's chosen editing style continually keeps the audience at an arm's length. The closest he comes to true pathos is with the park-bench sequence, when an old man offers some bread and meat to the famished woman, delicately avoiding eye contact to preserve her dignity. Even in this scene, the montage style intrudes. A director like Chaplin (and I'm a romantic at heart, so he's naturally one of favourite filmmakers) would have placed the camera at a distance, framing the profiles of both the woman and the old man within the same shot, thus capturing the subtle emotions and inflections of both parties simultaneously. Kirsanoff somewhat confuses the scene, cutting sequentially between the woman, the man and the food in a manner that reduces a simple, poignant act of kindness into a technical exercise in film editing. It works adequately, of course, a precise demonstration of the Kuleshov Effect, but there's relatively little heart in it.

But we'll cease with my complaints hereafter. I know my own film tastes well enough to recognise that what I disliked about the film its emotional distance, for example represents precisely what others love about it. There's no doubting that the photography (when it's kept on screen long enough) is breathtakingly spectacular, making accomplished use of lighting, shadows and in-camera optical effects such as dissolves, irises and superimpositions. There are touches of the surreal. Kirsanoff cuts non-discriminately forwards in time, backwards and into his characters' dreams, fragmenting time and reality into a series of shattered images, their individual meanings obscure until considered sequentially as in the pieces of a puzzle. Most impressive, I thought, was how several shots captured the linear perspective of roads and alleys, watching his characters gradually depart into the distance as though merely following the predetermined pathways of their future. The film ends exactly as it begins with a bloody and unexplained murder suggesting the inevitable cycle of human suffering, its causes unknown and forever incomprehensible.

I think "Menilmontant" is one of the great masterpieces of the silent era, and upon reading the comments posted, felt that it needed a little support. (If for nothing else than to encourage other people to seek it out, if not on video -- currently the only videos of this film have copied it at the wrong projection, thereby cranking up the film's speed and changing the running time from approximately 35 to 20 mins. -- than at a local museum or revival house; at least until someone puts out a definitive copy on video or DVD.)

Dimitri Kirsanoff's film centers on two young country girls who flee to the city after their parents are brutally murdered (we are given very few details as to who did this or why). The film's narrative is very sketchy, as there are no intertitles, and the two girls have similar features and are dressed similarly throughout most of the film. One of the girls, played by the wonderful Nadia Sibirskaia (Kirsanoff's wife), goes off with a man while her sister stays home in their tenement. When she returns home she soon has a baby, and her sister goes off (presumably as a prostitute) with the man. Sibirskaia presumably becomes homeless until she is ultimately reunited with her sister. The man they went away with earlier shows up again, only to be killed by a random criminal.

The film's slim and fragmented plot does nothing to convey the extraordinary and evocative world Kirsanoff creates through a barrage of disparate techniques lifted from German expressionism, Soviet montage, Hollywood melodrama, and the French avant-garde. The opening massacre is shown through a rapid Eisenstein-inspired montage; the compression of time and dreamlike waywardness of the girls' journey is presented through a series of lap dissolves; and the wintry, desolate atmosphere of Menilmontant (a poor, working class district on the eastern edge of Paris) is conveyed by an impressionistic use of documentary footage.

The film's most celebrated sequence occurs while Sibirskaia is wandering destitute on the streets of Paris (after contemplating drowning herself and her baby). Alone at night on a park bench, the young mother is cold and hungry, when an old man with a cane sits down on the bench next to her. The old man quietly shares some of his bread with her (never looking at her, he only lays the scraps and pieces on the bench separating them). The desperate girl tearfully accepts the food, and smiles, though the man barely looks her way. It's an extraordinarily sad and moving sequence that has echoes of Chaplin, but without that comedian's maudlin approach to sentiment. Sibirskaia's performance here is wonderfully nuanced and naturalistic -- there's very little of the histrionics usually associated with much silent film acting -- and she possesses a face that rivals Lillian Gish. The only comparable sequence I can think of is in Ozu's great 1935 silent film, An Inn in Tokyo.

In spite of its short length, this a film overflowing with riches. It ranks with the best films of any year.

Dimitri Kirsanoff's film centers on two young country girls who flee to the city after their parents are brutally murdered (we are given very few details as to who did this or why). The film's narrative is very sketchy, as there are no intertitles, and the two girls have similar features and are dressed similarly throughout most of the film. One of the girls, played by the wonderful Nadia Sibirskaia (Kirsanoff's wife), goes off with a man while her sister stays home in their tenement. When she returns home she soon has a baby, and her sister goes off (presumably as a prostitute) with the man. Sibirskaia presumably becomes homeless until she is ultimately reunited with her sister. The man they went away with earlier shows up again, only to be killed by a random criminal.

The film's slim and fragmented plot does nothing to convey the extraordinary and evocative world Kirsanoff creates through a barrage of disparate techniques lifted from German expressionism, Soviet montage, Hollywood melodrama, and the French avant-garde. The opening massacre is shown through a rapid Eisenstein-inspired montage; the compression of time and dreamlike waywardness of the girls' journey is presented through a series of lap dissolves; and the wintry, desolate atmosphere of Menilmontant (a poor, working class district on the eastern edge of Paris) is conveyed by an impressionistic use of documentary footage.

The film's most celebrated sequence occurs while Sibirskaia is wandering destitute on the streets of Paris (after contemplating drowning herself and her baby). Alone at night on a park bench, the young mother is cold and hungry, when an old man with a cane sits down on the bench next to her. The old man quietly shares some of his bread with her (never looking at her, he only lays the scraps and pieces on the bench separating them). The desperate girl tearfully accepts the food, and smiles, though the man barely looks her way. It's an extraordinarily sad and moving sequence that has echoes of Chaplin, but without that comedian's maudlin approach to sentiment. Sibirskaia's performance here is wonderfully nuanced and naturalistic -- there's very little of the histrionics usually associated with much silent film acting -- and she possesses a face that rivals Lillian Gish. The only comparable sequence I can think of is in Ozu's great 1935 silent film, An Inn in Tokyo.

In spite of its short length, this a film overflowing with riches. It ranks with the best films of any year.

Dmitri Kirsinov's Menilmontant is considered to be a landmark in the art of film-making. The story is sparse, melodramatic, and brief. The film is barely twenty minutes long. A young girl leaves home after a somewhat vague hatchet murder takes place. She spends time in the seedy streets of Menilmontant, a medieval suburb of Paris. She drifts through a relationship with her sister and man friend.

If you are looking for a strong story and character development, you may be missing the point. Kirsanov was trying to manipulate images in such a way as to get a reaction from his viewer. The bigger story is just a convention on which to hang his moody images. The axe murder with its choppy editing is a very early use of this sort of emotive technique. You are one moment under the flailing axe, interleaved with fast cuts of a howling victim. Later in the film the younger sister is the center of a blurry sensual reverie, her body and her grim surroundings in and out of focus. Silent film as art needs to be taken on its own terms. Kirsanov and other early filmmakers helped to define the way we view, and how we understand the film narrative. That understanding of how the film story works was established quite some time ago, which needs remembering by those of us not around in 1926. It was not foreordained that fast editing, double exposure and other techniques would come into their own. Someone had to prove the power of a restrained use of these formal ideas. Kirsanov did this in 1926.

If you are looking for a strong story and character development, you may be missing the point. Kirsanov was trying to manipulate images in such a way as to get a reaction from his viewer. The bigger story is just a convention on which to hang his moody images. The axe murder with its choppy editing is a very early use of this sort of emotive technique. You are one moment under the flailing axe, interleaved with fast cuts of a howling victim. Later in the film the younger sister is the center of a blurry sensual reverie, her body and her grim surroundings in and out of focus. Silent film as art needs to be taken on its own terms. Kirsanov and other early filmmakers helped to define the way we view, and how we understand the film narrative. That understanding of how the film story works was established quite some time ago, which needs remembering by those of us not around in 1926. It was not foreordained that fast editing, double exposure and other techniques would come into their own. Someone had to prove the power of a restrained use of these formal ideas. Kirsanov did this in 1926.

The Ménilmontant depicted here by Dimitri Kirsanofff is a far cry from the picturesque village of Charles Trenet's famous chanson. The grim and narrow cobbled streets provide a backdrop for a film of which the subject matter is that of conventional melodrama but which has been raised by Dimitri Kirsanoff to the level of cinematic art.

The stylistic effects he employs are those of Impressionism, notably rapid montage, superimposition and flashbacks but never at the expense of the narrative and nigh-on a century later the film's emotive power has not diminished and remains a devastating piece of social realism which concerns two orphaned sisters who are eventually reconciled, having been betrayed by the same man.

Suffice to say the lynchpin is the director's wife and muse Nadia Sibirskaia whose face is adored by the camera and whose performance as the younger sister is stunning in its simplicity.

The mood of the film is heightened by the newly composed score of the talented Paul Mercer.

This is the second and indeed oldest surviving film of Russian émigré Kirsanoff and although to my knowledge he never again reached such heights this piece of ciné poetry guarantees his immortality.

The stylistic effects he employs are those of Impressionism, notably rapid montage, superimposition and flashbacks but never at the expense of the narrative and nigh-on a century later the film's emotive power has not diminished and remains a devastating piece of social realism which concerns two orphaned sisters who are eventually reconciled, having been betrayed by the same man.

Suffice to say the lynchpin is the director's wife and muse Nadia Sibirskaia whose face is adored by the camera and whose performance as the younger sister is stunning in its simplicity.

The mood of the film is heightened by the newly composed score of the talented Paul Mercer.

This is the second and indeed oldest surviving film of Russian émigré Kirsanoff and although to my knowledge he never again reached such heights this piece of ciné poetry guarantees his immortality.

¿Sabías que…?

- TriviaPauline Kael said this was her favorite film of all time.

- Versiones alternativasThis film was published in Italy in an DVD anthology entitled "Avanguardia: Cinema sperimentale degli anni '20 e '30", distributed by DNA Srl. The film has been re-edited with the contribution of the film history scholar Riccardo Cusin . This version is also available in streaming on some platforms.

- ConexionesFeatured in The language of the silent cinema 1895-1929 - Part II: 1926-1929 (1973)

Selecciones populares

Inicia sesión para calificar y agrega a la lista de videos para obtener recomendaciones personalizadas

Detalles

- Tiempo de ejecución38 minutos

- Color

- Mezcla de sonido

- Relación de aspecto

- 1.33 : 1

Contribuir a esta página

Sugiere una edición o agrega el contenido que falta

Principales brechas de datos

By what name was Ménilmontant (1926) officially released in Canada in English?

Responda