Kárhozat

- 1988

- 2h

CALIFICACIÓN DE IMDb

7.6/10

7.2 k

TU CALIFICACIÓN

Agrega una trama en tu idiomaA lonely barfly falls in love with a married bar singer.A lonely barfly falls in love with a married bar singer.A lonely barfly falls in love with a married bar singer.

- Dirección

- Guionistas

- Elenco

- Premios

- 2 premios ganados y 1 nominación en total

- Dirección

- Guionistas

- Todo el elenco y el equipo

- Producción, taquilla y más en IMDbPro

Opiniones destacadas

Okay, so my ongoing project is that I'm seeking out films where as you watch the self who sees comes into focus. The most clear and direct way is with slow filmmakers like Tarr and others, though it's a lost game if you let them simply numb you. Others like Greenaway, Lynch and Ruiz will do it by tricking you into invented realities, another boat down the same river.

Usually there's some impatience, a trying to figure things out, a disorientation is central among these filmmakers as the first step. As you quiet down that impatient self, and films of this sort help, things become clearer, unusual insights appear. But it also helps to see past the filmmaker, most of the time he imposes on his created world by trying to explain (usually through a surrogate self) some part of it, reducing.

Also clear, in this case it's the protagonist philosophizing on meaningless life, impossible salvation and the ruin of having to be, dreary stuff. Because he is the protagonist, we think some of it will shed some light. But that's just who Tarr is, gloomy, wondering. I don't doubt his sincere despair. But what's the use? Rest there and he'll suffocate you, stain you without cleansing.

Anyway, discard all that, and it can be a different experience. It's a worthy film beneath the mud.

It's a simple story, a schmuck is contracted to smuggle in a parcel, we can assume by the secrecy that it's some shady deal. In turn he contracts the husband of a woman he's having an affair with—a sexy torch singer. As the husband goes away, we go on to visit disconnected stops in this affair, this is what gives the film its dreamlike air. So that's the story.

More interesting is the world behind it. Your clue is a recurring visual motif introduced with just the first shot—a hazy view of something, and pan to reveal someone watching, an intermediate self between you and things. He IS constantly obscuring the view by thinking what it's about. The second time it's like in a film noir, it's raining, a man is watching a bar. Inside the bar, we are seduced by the femme fatale's smoky song, maybe it's all a nightmare as the lyrics say.

It's a wonderful scene that sets everything else up.

So as per noir rules, desire fools with the schmuck's sense of reality and we have the rest of the film as hazy perturbation. He has done something wrong and knows it, sending the husband away. The third time the watcher motif appears, the woman is not looking out to life through the blinds, but inside the room, her gaze cramped by walls of his desire —the scene plays out with sex, mirrored in a mirror reinforcing inversed reality.

So the affair grows stale—and lo, we have his endless monologues rationalizing frustration by directing it to the world, the world as punishment. And that as profundity that distracts.

So who is obscuring the view?

It's that intermediate self who instead of seeing, fidgets for more story and answers that preferably make some sense. It's your own self, fidgeting for more story when you watch a film like this.

Isn't this something that actually happens? As you watch these ultra slow films, which is why they can help, doesn't your own fidgety self distract you by aimless thinking? Isn't that self getting in the way of what is potentially there for you? Imagine if Tarr acknowledged the fact in his narration, for instance like Nabokov does with self-deprecating layered humor—it'd be an astounding film.

Tarr has set up other cool things, the husband knowing something is wrong as our guy's guilt, an older woman (his woman) suggesting peace in the dance together. But there are moments like when she quotes the Bible and the inane end with the dog, which muddle what it is about. Tarr was probably unsure himself, the interested part of him doing the noir abstraction, another part of him venting.

But the scene at the bar, her song as noir hallucination. The architecture and roaming camera as in Marienbad. And all of it submerged as different levels of watching. I'd like to think Lynch saw this, and immediately knew which parts worked. Tarr is probably still unsure.

Usually there's some impatience, a trying to figure things out, a disorientation is central among these filmmakers as the first step. As you quiet down that impatient self, and films of this sort help, things become clearer, unusual insights appear. But it also helps to see past the filmmaker, most of the time he imposes on his created world by trying to explain (usually through a surrogate self) some part of it, reducing.

Also clear, in this case it's the protagonist philosophizing on meaningless life, impossible salvation and the ruin of having to be, dreary stuff. Because he is the protagonist, we think some of it will shed some light. But that's just who Tarr is, gloomy, wondering. I don't doubt his sincere despair. But what's the use? Rest there and he'll suffocate you, stain you without cleansing.

Anyway, discard all that, and it can be a different experience. It's a worthy film beneath the mud.

It's a simple story, a schmuck is contracted to smuggle in a parcel, we can assume by the secrecy that it's some shady deal. In turn he contracts the husband of a woman he's having an affair with—a sexy torch singer. As the husband goes away, we go on to visit disconnected stops in this affair, this is what gives the film its dreamlike air. So that's the story.

More interesting is the world behind it. Your clue is a recurring visual motif introduced with just the first shot—a hazy view of something, and pan to reveal someone watching, an intermediate self between you and things. He IS constantly obscuring the view by thinking what it's about. The second time it's like in a film noir, it's raining, a man is watching a bar. Inside the bar, we are seduced by the femme fatale's smoky song, maybe it's all a nightmare as the lyrics say.

It's a wonderful scene that sets everything else up.

So as per noir rules, desire fools with the schmuck's sense of reality and we have the rest of the film as hazy perturbation. He has done something wrong and knows it, sending the husband away. The third time the watcher motif appears, the woman is not looking out to life through the blinds, but inside the room, her gaze cramped by walls of his desire —the scene plays out with sex, mirrored in a mirror reinforcing inversed reality.

So the affair grows stale—and lo, we have his endless monologues rationalizing frustration by directing it to the world, the world as punishment. And that as profundity that distracts.

So who is obscuring the view?

It's that intermediate self who instead of seeing, fidgets for more story and answers that preferably make some sense. It's your own self, fidgeting for more story when you watch a film like this.

Isn't this something that actually happens? As you watch these ultra slow films, which is why they can help, doesn't your own fidgety self distract you by aimless thinking? Isn't that self getting in the way of what is potentially there for you? Imagine if Tarr acknowledged the fact in his narration, for instance like Nabokov does with self-deprecating layered humor—it'd be an astounding film.

Tarr has set up other cool things, the husband knowing something is wrong as our guy's guilt, an older woman (his woman) suggesting peace in the dance together. But there are moments like when she quotes the Bible and the inane end with the dog, which muddle what it is about. Tarr was probably unsure himself, the interested part of him doing the noir abstraction, another part of him venting.

But the scene at the bar, her song as noir hallucination. The architecture and roaming camera as in Marienbad. And all of it submerged as different levels of watching. I'd like to think Lynch saw this, and immediately knew which parts worked. Tarr is probably still unsure.

An exceptionally brilliant movie. But this is not for everyone. Beautifully shot in black and white, the director bravely specialises in spectacularly lengthy shots which the viewer's brain will either become absorbed by or reject for tedium. An interesting dimension which can heighten involvement in these long shots (or annoy the hell out the unconvinced) is rhythmical sound - be it cranky machinery (like the relentless mechanical pulley system outside the 'central' character's window) or people dancing to cabaret music. There is a detachment to the camera-work, particularly in the dance band sequences, which reminded me of Kubrick. Again this is an approach which will alienate many viewers but it lends a kind of philosophical power what would otherwise be mundane documentary social observation.

I watched this after the more recent Werckmeister Harmonies on the current double-disc DVD edition available in the UK which is a superb issue and has an interview with the Director as a bonus feature. Interesting to note that he states quite categorically that he intends no allegorical/symbolic element to his work.

I watched this after the more recent Werckmeister Harmonies on the current double-disc DVD edition available in the UK which is a superb issue and has an interview with the Director as a bonus feature. Interesting to note that he states quite categorically that he intends no allegorical/symbolic element to his work.

Damnation (1988) ****

Although he made a number of feature films previous to Damnation, this is where Bela Tarr found his trademark style. It was also his first collaboration with novelist and country man Laszlo Krasznahorkai; a collaboration which continues to this day.

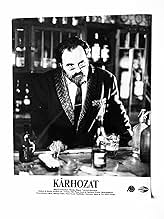

The film opens with now trademark Tarr style, watching mining carts travel along with their loads for a few minutes (yes minutes). The camera slowly pulls back to reveal Karrer (Miklós Székely) shaving. He's a lonely loser, slowly drinking himself to death at the Titanik Bar. He is in love with and sleeping with the lounge singer there (Vali Kerekes). The problem, however, is that she is married, and has made no secret of wanting to end their affair. That when he asks her why she doesn't love him, and she replies "I love you and you know it," is of no real matter to her.

Karrer is offered a smuggling job by the bar's shady owner. He decides to offer the job to the singer's husband, who has built up a substantial debt and is in danger of being imprisoned for it. He accepts, and Karrer wins himself three days to swoon the singer. She denies him, nevertheless sleeping with him in perhaps the least passionate sex scene ever filmed. A bitter Karrer decides he will turn in to the authorities her husband when he returns from his smuggling job, leaving her alone and thus making him now the logical option. By the end, the lives of Damnation's characters will be as broken and desolate as the crumbling town in which they live.

Damnation plays as love triangle, grounded out over nearly two hours. Tarr's long shots and elegantly bleak black and white photography follows ever so slowly the action. The lighting is impeccable, creating ghostly silhouettes, dusty and dim barrooms, and elegant and shimmering light bouncing of the face and hair of the lounge singer. As characteristic of Bela Tarr, the cinematography is stately and assured, breathtaking and deliberate. He films his characters and their town as assuredly and respectfully as possible. The town, and the dogs which walk its streets, hint at the apocalyptic undertones of the film, and transcends all emotions, or lack there of.

I have had reservations about Damnation in the past, confident that it was film-making at its very best, sublimely atmospheric and tonal, but unsure whether or not just how well it worked, particularly in relation to Tarr's two formidable masterpieces, Satantango and Werckmeister Harmonies. Those films have something mammoth and intimidating about them: Satantango, with its titanic length, clocking in at over 7 hours, all in the same style and minimal narrative; Werckmeister Harmonies with its bizarre metaphysical underpinnings and suggestive philosophy. Those films have a ground out dreamlike or perhaps nightmarish quality to them, particular Werckmeister Harmonies. After my fourth of fifth viewing of Damnation, I'm now assured that it does in fact work particularly when you avoid getting hung up on Tarr's other films. I'm also assured of its greatness. Damnation is a masterpiece of film-making. It draws parallels with the Italian realist films of the 50s and early 60s, as well as the minimalist transcendentalism of the films of Robert Bresson, but all the while invoking a dreamlike quality that keeps the viewer removed at just the right distance for a gritty but transcendent experience.

Although he made a number of feature films previous to Damnation, this is where Bela Tarr found his trademark style. It was also his first collaboration with novelist and country man Laszlo Krasznahorkai; a collaboration which continues to this day.

The film opens with now trademark Tarr style, watching mining carts travel along with their loads for a few minutes (yes minutes). The camera slowly pulls back to reveal Karrer (Miklós Székely) shaving. He's a lonely loser, slowly drinking himself to death at the Titanik Bar. He is in love with and sleeping with the lounge singer there (Vali Kerekes). The problem, however, is that she is married, and has made no secret of wanting to end their affair. That when he asks her why she doesn't love him, and she replies "I love you and you know it," is of no real matter to her.

Karrer is offered a smuggling job by the bar's shady owner. He decides to offer the job to the singer's husband, who has built up a substantial debt and is in danger of being imprisoned for it. He accepts, and Karrer wins himself three days to swoon the singer. She denies him, nevertheless sleeping with him in perhaps the least passionate sex scene ever filmed. A bitter Karrer decides he will turn in to the authorities her husband when he returns from his smuggling job, leaving her alone and thus making him now the logical option. By the end, the lives of Damnation's characters will be as broken and desolate as the crumbling town in which they live.

Damnation plays as love triangle, grounded out over nearly two hours. Tarr's long shots and elegantly bleak black and white photography follows ever so slowly the action. The lighting is impeccable, creating ghostly silhouettes, dusty and dim barrooms, and elegant and shimmering light bouncing of the face and hair of the lounge singer. As characteristic of Bela Tarr, the cinematography is stately and assured, breathtaking and deliberate. He films his characters and their town as assuredly and respectfully as possible. The town, and the dogs which walk its streets, hint at the apocalyptic undertones of the film, and transcends all emotions, or lack there of.

I have had reservations about Damnation in the past, confident that it was film-making at its very best, sublimely atmospheric and tonal, but unsure whether or not just how well it worked, particularly in relation to Tarr's two formidable masterpieces, Satantango and Werckmeister Harmonies. Those films have something mammoth and intimidating about them: Satantango, with its titanic length, clocking in at over 7 hours, all in the same style and minimal narrative; Werckmeister Harmonies with its bizarre metaphysical underpinnings and suggestive philosophy. Those films have a ground out dreamlike or perhaps nightmarish quality to them, particular Werckmeister Harmonies. After my fourth of fifth viewing of Damnation, I'm now assured that it does in fact work particularly when you avoid getting hung up on Tarr's other films. I'm also assured of its greatness. Damnation is a masterpiece of film-making. It draws parallels with the Italian realist films of the 50s and early 60s, as well as the minimalist transcendentalism of the films of Robert Bresson, but all the while invoking a dreamlike quality that keeps the viewer removed at just the right distance for a gritty but transcendent experience.

I watch Bela Tarr's films over again with endless fascination. The length is not a problem: No longer that many pieces of music. If you can concentrate through a Wagner opera and I hope you can, then a Tarr film is not very long. All the films are very much products of team work but lead by an autocratic man who knows exactly what he wants, hence the seam free quality of the experience, It is that, rather than the length which requires the concentration. I have not found it mentioned often enough but there is much humour in his films, Karrer does a reprise of Gene Kelly, which is then itself parodied near the end of the film. Damnation is maybe still my favourite, I suppose for the mesmerising way sound is used to structure a complex web of association, but then all of the available late films has so much to offer

The film that launched director Béla Tarr into international attention, Kárhozat is the Hungarian's first major investigation of the nature of humanity.

Trailing the exploits of alcoholic depressive Karrer, Kárhozat presents us with a view of a desolate and decrepit Hungarian town. He spends his days wandering from bar to bar, obsessing over a married lounge singer and part-time lover whom he longs to elope with. Passing off a job to collect a package to the husband, he buys himself three days alone with the object of his desires.

As is now his trademark, Tarr brings us the minimal number of shots: slow, winding, thoughtful and beautiful. His approach is simultaneously simple and complicated, showing us at the same time nothing and everything. The aesthetic of the film is astounding, beauty created wonderfully in the chaos and destruction of the landscape. The brooding intensity of the omnipresent coal trains dominates the work, an indicator of lost industry and decline. Miklós Székely leads the cast with the perfect stoic facade, his granite face holding back the weight of an emotional past and the crippling need for escape. The sinister and critical bartender gives us Karrer's true opinion of himself, one he would rather not face up to, whilst the sagacious old woman provides the film's sensibility and reason. The plot itself is not so important as the camera's journey and the character's silent ruminations, leading unavoidably to a wonderful climax and one which does exactly what it should: causes us to question our own lives and the oddity of humankind.

With beautiful, paced, unconventional direction, Tarr gives us an intimate portrait of ourselves and our world. Achieving an incredible amount with a minimalistic approach, the film is entrancing, mysterious, and inspiring. Telling us as much with his landscapes as with his characters, Tarr's Kárhozat is a testament to the brilliance of this creative juggernaut.

Trailing the exploits of alcoholic depressive Karrer, Kárhozat presents us with a view of a desolate and decrepit Hungarian town. He spends his days wandering from bar to bar, obsessing over a married lounge singer and part-time lover whom he longs to elope with. Passing off a job to collect a package to the husband, he buys himself three days alone with the object of his desires.

As is now his trademark, Tarr brings us the minimal number of shots: slow, winding, thoughtful and beautiful. His approach is simultaneously simple and complicated, showing us at the same time nothing and everything. The aesthetic of the film is astounding, beauty created wonderfully in the chaos and destruction of the landscape. The brooding intensity of the omnipresent coal trains dominates the work, an indicator of lost industry and decline. Miklós Székely leads the cast with the perfect stoic facade, his granite face holding back the weight of an emotional past and the crippling need for escape. The sinister and critical bartender gives us Karrer's true opinion of himself, one he would rather not face up to, whilst the sagacious old woman provides the film's sensibility and reason. The plot itself is not so important as the camera's journey and the character's silent ruminations, leading unavoidably to a wonderful climax and one which does exactly what it should: causes us to question our own lives and the oddity of humankind.

With beautiful, paced, unconventional direction, Tarr gives us an intimate portrait of ourselves and our world. Achieving an incredible amount with a minimalistic approach, the film is entrancing, mysterious, and inspiring. Telling us as much with his landscapes as with his characters, Tarr's Kárhozat is a testament to the brilliance of this creative juggernaut.

¿Sabías que…?

- TriviaWith "Kárhozat / Damnation", the first of his collaborations with novelist Laszlo Krasznahorkai, Bela Tarr adopts a formally rigorous style, featuring long takes and slow tracking shots of the bleak landscape that surrounds the characters.

- ErroresIn the Dance/Party scene, the band and the music are clearly out of sync.

- Citas

The Singer: I like the rain. I like to watch the water run down the window. It calms me down. I don't think about anything. I just watch the rain.

- ConexionesEdited into Gli ultimi giorni dell'umanità (2022)

Selecciones populares

Inicia sesión para calificar y agrega a la lista de videos para obtener recomendaciones personalizadas

- How long is Damnation?Con tecnología de Alexa

Detalles

- Tiempo de ejecución2 horas

- Color

- Mezcla de sonido

- Relación de aspecto

- 1.66 : 1

Contribuir a esta página

Sugiere una edición o agrega el contenido que falta

Principales brechas de datos

By what name was Kárhozat (1988) officially released in India in English?

Responda