CALIFICACIÓN DE IMDb

7.7/10

20 k

TU CALIFICACIÓN

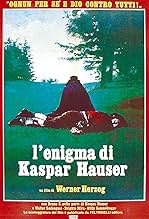

Un joven apenas capaz de hablar y caminar, y portando una extraña nota aparece repentinamente en Núremberg en 1828.Un joven apenas capaz de hablar y caminar, y portando una extraña nota aparece repentinamente en Núremberg en 1828.Un joven apenas capaz de hablar y caminar, y portando una extraña nota aparece repentinamente en Núremberg en 1828.

- Dirección

- Guionistas

- Elenco

- Premios

- 5 premios ganados y 3 nominaciones en total

- Dirección

- Guionistas

- Todo el elenco y el equipo

- Producción, taquilla y más en IMDbPro

Opiniones destacadas

One of the most evocative and quietly moving films ever produced on the subjects of cultural displacement, exploitation and personal despair, with director Werner Herzog producing a pure work of cinema as sensitive as the character that he depicts. With this particular film, Herzog created perhaps the ultimate statement about the perseverance of the human spirit, whilst simultaneously creating a world that is deliberately abstracted in order to convey the perspective of a character out of step with society and the period that embraced him. Like many of Herzog's films from this era, such as Even Dwarfs Started Small (1970) and Stroszek (1977) in particular, The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (1975) is essentially about looking at the world from the outside in; with all of the separate elements distorted in order to convey the world-view of this perennial outsider seeing himself for the very first time. In a manner similar to that of David Lynch's subsequent film, The Elephant Man (1980), Herzog uses elements of the real-life story behind the character simply as an excuse to ruminate on the notions of alienation, the nature of conspiracy, personal exploitation and degradation, as well as the often underhanded mechanisms of a seemingly enlightened society, in a way that goes beyond the mere superficial levels of the narrative.

The point of the film is expressed by the original German title, "Jeder für sich und Gott gegen alle", or "every man for himself and God against all". In keeping with this, the nature of religion is brought up twice in the film and dismissed on both occasions by the central character, who claims to be too unfamiliar with the concept of spirituality to be able to make an informed opinion. The church argues that Kaspar should believe simply as an act of blind faith and that a leap of faith will overcome any such notions of knowledge or conception. It is a keen comment on the part of Herzog and one that ties into the idea of Kaspar as an unspoiled being; an almost childlike figure, though in the possession of a keen intelligence and a passionate creative spirit, who ultimately finds himself persecuted for reasons that neither he nor we could ever truly comprehend. In the hands of any other filmmaker, the depiction of Kaspar would have no doubt been that of the traditional outcast; desperately trying to find their own identity in the form of a triumph over adversity. However - again looking back to the subject matter of Even Dwarfs Started Small - Herzog instead gives us a representation of the sane man in the insane world; showing us how the corruption and inherent evil of self-preservation can take a gentle and contemplative spirit and crush it completely; a notion that is beautifully illustrated in a cinematic sense by the scene in which Kaspar sows his name with seeds into the flower bed, only to return one day from an outing to find that it has been trampled by an intruder.

Moments like these are characteristic of Herzog's continually fascinating style of direction from this particular period, as he approached cinema from a perspective similar to that of filmmakers like Peter Watkins, Ken Russell or Pier Paolo Pasolini by investigating the workings of a period setting from a more contemporary perspective. So, we have the authentic costumes, locations and an attempt to recreate the values and mannerisms of this particular society, all the while being abstracted by Herzog's continually probing camera that lingers and explores - often hand-held - through the various cobbled back-streets and stately homes from where the drama plays out. Herzog has often claimed that there is (or was) no real distinction between his documentary work and his more cinematic features, with both particular examples coming from the same place and attempting to convey what Herzog refers to as "the ecstatic truth". You can see this ideology clearly with the film, as the director mixes a non-actor in the shape of Bruno S. alongside professional performers like Walter Ladengast and Brigitte Mira. As a result of this, there is a heightened quality to the portrayal of Kaspar, as well as a genuine sense of dependence on the two characters that come to care for him, as the more experienced cast members take Bruno under their wing and coach him along in a manner reminiscent of the actual characters themselves.

The juxtaposition between the two styles of documentary realism and purposeful cinematic expression can be seen in the visualisation of the film; from the naturalistic cinematography of Jörg Schmidt-Reitwein - with its emphasis on light and shadow and expressive use of landscapes - to the use of classical music (which here gives the film a yearning, almost romantic sense of melodrama to contrast against the more downbeat elements of the film). From its stark and impressionistic opening vignette - with its allusions to a dreamlike evocation somewhat removed from the rest of the film - to the beguiling fever-dream of caravans moving through a barren desert as the film reaches its close, The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser is an absolute masterpiece from a director here at the very top of his creative peak. It is without question unlike any other film you will ever see; one that is rich in character and a believable evocation of period detail, but one that also presents a genuinely unique and unforgettable cinematic vision. In Herzog's film, it is the world that is wrong and confused, with Kaspar becoming a sort of representation for the very greatest qualities of humanity in the face of this vile corruption. A powerful and emotive concept as passionately realised as the film itself.

The point of the film is expressed by the original German title, "Jeder für sich und Gott gegen alle", or "every man for himself and God against all". In keeping with this, the nature of religion is brought up twice in the film and dismissed on both occasions by the central character, who claims to be too unfamiliar with the concept of spirituality to be able to make an informed opinion. The church argues that Kaspar should believe simply as an act of blind faith and that a leap of faith will overcome any such notions of knowledge or conception. It is a keen comment on the part of Herzog and one that ties into the idea of Kaspar as an unspoiled being; an almost childlike figure, though in the possession of a keen intelligence and a passionate creative spirit, who ultimately finds himself persecuted for reasons that neither he nor we could ever truly comprehend. In the hands of any other filmmaker, the depiction of Kaspar would have no doubt been that of the traditional outcast; desperately trying to find their own identity in the form of a triumph over adversity. However - again looking back to the subject matter of Even Dwarfs Started Small - Herzog instead gives us a representation of the sane man in the insane world; showing us how the corruption and inherent evil of self-preservation can take a gentle and contemplative spirit and crush it completely; a notion that is beautifully illustrated in a cinematic sense by the scene in which Kaspar sows his name with seeds into the flower bed, only to return one day from an outing to find that it has been trampled by an intruder.

Moments like these are characteristic of Herzog's continually fascinating style of direction from this particular period, as he approached cinema from a perspective similar to that of filmmakers like Peter Watkins, Ken Russell or Pier Paolo Pasolini by investigating the workings of a period setting from a more contemporary perspective. So, we have the authentic costumes, locations and an attempt to recreate the values and mannerisms of this particular society, all the while being abstracted by Herzog's continually probing camera that lingers and explores - often hand-held - through the various cobbled back-streets and stately homes from where the drama plays out. Herzog has often claimed that there is (or was) no real distinction between his documentary work and his more cinematic features, with both particular examples coming from the same place and attempting to convey what Herzog refers to as "the ecstatic truth". You can see this ideology clearly with the film, as the director mixes a non-actor in the shape of Bruno S. alongside professional performers like Walter Ladengast and Brigitte Mira. As a result of this, there is a heightened quality to the portrayal of Kaspar, as well as a genuine sense of dependence on the two characters that come to care for him, as the more experienced cast members take Bruno under their wing and coach him along in a manner reminiscent of the actual characters themselves.

The juxtaposition between the two styles of documentary realism and purposeful cinematic expression can be seen in the visualisation of the film; from the naturalistic cinematography of Jörg Schmidt-Reitwein - with its emphasis on light and shadow and expressive use of landscapes - to the use of classical music (which here gives the film a yearning, almost romantic sense of melodrama to contrast against the more downbeat elements of the film). From its stark and impressionistic opening vignette - with its allusions to a dreamlike evocation somewhat removed from the rest of the film - to the beguiling fever-dream of caravans moving through a barren desert as the film reaches its close, The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser is an absolute masterpiece from a director here at the very top of his creative peak. It is without question unlike any other film you will ever see; one that is rich in character and a believable evocation of period detail, but one that also presents a genuinely unique and unforgettable cinematic vision. In Herzog's film, it is the world that is wrong and confused, with Kaspar becoming a sort of representation for the very greatest qualities of humanity in the face of this vile corruption. A powerful and emotive concept as passionately realised as the film itself.

Werner Herzog's films reach emotional and aesthetic levels that few directors can aspire to. As one of the rare film-maker's more concerned with the artistry of their work than what they achieve at the box office, Herzog is nearly peerless in his purity and ideosynchrasy. Herzog uses the film medium as a moving canvas upon which he expresses, affects, and creates nightmares and dreamworlds which are so vividly real that they threaten our own naturalized consciousness of the projection we call reality.

So much for the postmodern gobbledygook. As you can tell, I love Herzog.

This early film deals with many of the familiar elements that tend to permeate Herzog's films - cultural critique, the insanity of everyday life, alienation, cruelty and power. But here, Herzog uses a true story of 19th century Europe as a vehicle, and treats his subject with an unusual compassion and straightforwardness.

Herzog's incredible casting talent also shows here, just as it does in all of his films. I do not wish to take anything away from the great performers, but really, how does one manage to choose an actor whose life experience is broadly similar to that of Kaspar Hauser's without knowing of it beforehand? This film blends somewhat disjointed artistic imagery with the true story of Kaspar Hauser, a man apart from society who has been kept in a cellar all of his life, and is suddenly expelled into the light in Nuremburg. He is adopted by a kindly old gent who attempts to socialize him in what appears to Kaspar (and perhaps to us through the film's clear vision) an insane society full of lies and contradictions. All of this is done with the believability that is so consistent in Herzog's theatricality, and the visual quality that qualifies him as a true cinematographic artist.

So much for the postmodern gobbledygook. As you can tell, I love Herzog.

This early film deals with many of the familiar elements that tend to permeate Herzog's films - cultural critique, the insanity of everyday life, alienation, cruelty and power. But here, Herzog uses a true story of 19th century Europe as a vehicle, and treats his subject with an unusual compassion and straightforwardness.

Herzog's incredible casting talent also shows here, just as it does in all of his films. I do not wish to take anything away from the great performers, but really, how does one manage to choose an actor whose life experience is broadly similar to that of Kaspar Hauser's without knowing of it beforehand? This film blends somewhat disjointed artistic imagery with the true story of Kaspar Hauser, a man apart from society who has been kept in a cellar all of his life, and is suddenly expelled into the light in Nuremburg. He is adopted by a kindly old gent who attempts to socialize him in what appears to Kaspar (and perhaps to us through the film's clear vision) an insane society full of lies and contradictions. All of this is done with the believability that is so consistent in Herzog's theatricality, and the visual quality that qualifies him as a true cinematographic artist.

Werner Herzog's strange and enticing film divulges only what is known of the account of Kaspar Hauser, played by Bruno S., who dwelled for the first 17 years of his life shackled in a small basement room with nothing more than a toy horse to occupy him, without all contact with humans or other living things save for a stranger who gives food to him. One day in 1828, the same anonymous figure takes Kaspar out of his chamber, schools him on a handful of expressions and how to walk, and then leaves him standing still in a cobblestone court in Nuremberg. Kaspar is the focus of novelty and interest and is even put on display in a circus before being saved by an aristocrat who slowly and good-naturedly endeavors to renovate him. Kaspar gradually learns to read and write and forms unorthodox perspectives on religion and logic, but music is what gives him great pleasure. He draws the attention of members of the clergy, professors, and aristocracy.

The most telling scene is in fact my favorite, when Kaspar is being schooled by a psychologist who asks him a classic brain-buster, to which Kaspar gives an effortless, unusual, perfectly legitimate answer that is swiftly rejected by the psychologist for not being the standard answer. The people surrounding Kaspar in Herzog's film are perfectly subjugated, as in the scene where a little girl tries to teach Kaspar a nursery rhyme, and while it's clear that he doesn't know the meaning at all of the rhyme like she does and that he hasn't even developed as far as a small child, it's also clear that the small child has not developed far enough to know how to educate someone with less common knowledge than her.

Herzog chronicles the real-life mystery of Kaspar Hauser not so much as a creepy mystery but as a character study that demonstrates that society's traditional manner of perceiving the world may not essentially be the most well-founded or defensible, hence the film's brilliant original title, Every Man For Himself and God Against All, as all but laid bare when Kaspar's assertion that apples are tired is apparently substantiated by the incapability of his aristocratic savior to show support of the argument that they are lifeless objects subject to human control.

Bruno S. is Herzog's beautiful achievement. Bruno S., the disdained son of a prostitute, was beaten so cruelly by his mother as a toddler that he fell deaf for awhile. This caused him to be institutionalized for the next 23 years in countless institutes, regularly committing petty crimes. Regardless of this horrendous history, he became an autodidactic painter and musician. At the same time as these were his beloved pursuits, he was also pressed to take jobs in factories. Herzog saw him in a 1970 documentary, he swore to work with him. In and of himself, Bruno S. attested to the power of Herzog's vision. He was exceptionally strenuous to work with, at times not so much wanting but requiring numerous hours of screaming a scene could be shot. Owing to all of this, Bruno S. literally is a Kaspar Hauser, an inordinately tortured soul utilized for the sake of revealing the shock value of reality's hidden ugliness to common society. Kaspar is taken under the wing of several groups of people but whether their intentions are good or bad, he can never seem to live a life without the exploitation of his completely removed mind for the commotion of nobility or business.

Short of an accepted narrative or dramatic construction and full of indistinct imagery generated only by Herzog's instinct, many unexplained elements never resolve themselves in Herzog's unique character study, and they shouldn't. His encapsulating only what the world knows of this very little-known story intensifies the intrigue of it. Why did this strange person do this to Kaspar Hauser? Who was he?

The most telling scene is in fact my favorite, when Kaspar is being schooled by a psychologist who asks him a classic brain-buster, to which Kaspar gives an effortless, unusual, perfectly legitimate answer that is swiftly rejected by the psychologist for not being the standard answer. The people surrounding Kaspar in Herzog's film are perfectly subjugated, as in the scene where a little girl tries to teach Kaspar a nursery rhyme, and while it's clear that he doesn't know the meaning at all of the rhyme like she does and that he hasn't even developed as far as a small child, it's also clear that the small child has not developed far enough to know how to educate someone with less common knowledge than her.

Herzog chronicles the real-life mystery of Kaspar Hauser not so much as a creepy mystery but as a character study that demonstrates that society's traditional manner of perceiving the world may not essentially be the most well-founded or defensible, hence the film's brilliant original title, Every Man For Himself and God Against All, as all but laid bare when Kaspar's assertion that apples are tired is apparently substantiated by the incapability of his aristocratic savior to show support of the argument that they are lifeless objects subject to human control.

Bruno S. is Herzog's beautiful achievement. Bruno S., the disdained son of a prostitute, was beaten so cruelly by his mother as a toddler that he fell deaf for awhile. This caused him to be institutionalized for the next 23 years in countless institutes, regularly committing petty crimes. Regardless of this horrendous history, he became an autodidactic painter and musician. At the same time as these were his beloved pursuits, he was also pressed to take jobs in factories. Herzog saw him in a 1970 documentary, he swore to work with him. In and of himself, Bruno S. attested to the power of Herzog's vision. He was exceptionally strenuous to work with, at times not so much wanting but requiring numerous hours of screaming a scene could be shot. Owing to all of this, Bruno S. literally is a Kaspar Hauser, an inordinately tortured soul utilized for the sake of revealing the shock value of reality's hidden ugliness to common society. Kaspar is taken under the wing of several groups of people but whether their intentions are good or bad, he can never seem to live a life without the exploitation of his completely removed mind for the commotion of nobility or business.

Short of an accepted narrative or dramatic construction and full of indistinct imagery generated only by Herzog's instinct, many unexplained elements never resolve themselves in Herzog's unique character study, and they shouldn't. His encapsulating only what the world knows of this very little-known story intensifies the intrigue of it. Why did this strange person do this to Kaspar Hauser? Who was he?

EVERY MAN FOR HIMSELF AND GOD AGAINST ALL (Werner Herzog - West Germany 1974).

Lacking a traditional narrative or dramatic structure and full of obscure images, this film feels more like a hypnotic dreamlike experience. It also features one the more enduring trends in Herzog's work: the featuring of individuals with exceptional physical or psychological conditions.

The film is based on the true story of Kaspar Hauser, a young man who suddenly appears on the market square in the German town of Nuremberg in 1828. This strange occurrence has become one of the most enduring inspirations in German history, literature and science, with well over a thousand books written on the case. When Kaspar Hauser was found, he could barely grunt, let alone speak and caused a minor sensation among the locals. After living in a cellar for years with only a pet rocking horse, he is abandoned by his protector and provider, the mysterious "Man in Black." Having been isolated from all humans except his mysterious protector, Kaspar is suddenly thrust into civilization, and is expected to adapt himself to 19th-century society. He becomes a public spectacle and everyone in town lines up to catch a glimpse of him. Soon the local officials in town decide he is too much of a (costly) burden and, in an attempt to profit from the public interest, he is turned over to a circus ringmaster, where he is added to the local carnival freak show, as one of "The Four Riddles of the Spheres." The other three include "a midget king", "A little Mozart" (an autistic or catatonic child), and a lute playing "savage". When Hauser comes under the tutelage of a sympathetic professor (Walter Ladengast), he gradually acquires an impressive degree of socialization and learns to express himself with a reasonable degree of clarity, but most of society's conventions, manners and thoughts is more the young man is able to adjust to.

Herzog adopted a technique of incorporating film material shot by others filmmakers into the film. Early on in the film, just before Kaspar is found on the town square, Herzog used material shot on super 8 of a Bavarian landscape and the town of Dinkelsbühl, that was almost disposed off, but Herzog thought it would be ideal for his film. These grainy shots, accompanied by a requiem of Orlando DiLasso, make for one of the most haunting images I've ever seen on film. Dream sequences are another important aspect in this film. In one of them, Kaspar Hauser has dream images of the Sahara desert, for which Herzog used material he shot in the Western Sahara on earlier occasions. I don't know of any other director who used this technique to such avail up until now. One of the most stunning scenes is when the "Man in black" leaves him with the shot on the mountain and soon after the music with the requiem starts. It's almost like a romantic twist on 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Herzog has done a fantastic job recounting the legend of Kaspar Hauser to the screen. The casting of Bruno S. in the role of Kaspar Hauser is of particular interest. He was a street artist in Berlin, when Herzog found him and decided he would be ideal to play the role of Kaspar Hauser. Before this, Bruno S. had a troubled past. After being severely beaten by his mother, he became deaf and was placed in an institution for retarded children at the age of three. At nine, when he tried to escape, he was transferred to a correctional institution. With further escape attempts, he amassed a number of criminal offenses and was incarcerated for more than twenty years. The authenticity of Bruno's performance brings such an element of sincerity to the film, that makes it almost impossible not to root for his cause. Bruno S. also starred in Herzog's STROSZEK (1976).

Camera Obscura --- 10/10

Lacking a traditional narrative or dramatic structure and full of obscure images, this film feels more like a hypnotic dreamlike experience. It also features one the more enduring trends in Herzog's work: the featuring of individuals with exceptional physical or psychological conditions.

The film is based on the true story of Kaspar Hauser, a young man who suddenly appears on the market square in the German town of Nuremberg in 1828. This strange occurrence has become one of the most enduring inspirations in German history, literature and science, with well over a thousand books written on the case. When Kaspar Hauser was found, he could barely grunt, let alone speak and caused a minor sensation among the locals. After living in a cellar for years with only a pet rocking horse, he is abandoned by his protector and provider, the mysterious "Man in Black." Having been isolated from all humans except his mysterious protector, Kaspar is suddenly thrust into civilization, and is expected to adapt himself to 19th-century society. He becomes a public spectacle and everyone in town lines up to catch a glimpse of him. Soon the local officials in town decide he is too much of a (costly) burden and, in an attempt to profit from the public interest, he is turned over to a circus ringmaster, where he is added to the local carnival freak show, as one of "The Four Riddles of the Spheres." The other three include "a midget king", "A little Mozart" (an autistic or catatonic child), and a lute playing "savage". When Hauser comes under the tutelage of a sympathetic professor (Walter Ladengast), he gradually acquires an impressive degree of socialization and learns to express himself with a reasonable degree of clarity, but most of society's conventions, manners and thoughts is more the young man is able to adjust to.

Herzog adopted a technique of incorporating film material shot by others filmmakers into the film. Early on in the film, just before Kaspar is found on the town square, Herzog used material shot on super 8 of a Bavarian landscape and the town of Dinkelsbühl, that was almost disposed off, but Herzog thought it would be ideal for his film. These grainy shots, accompanied by a requiem of Orlando DiLasso, make for one of the most haunting images I've ever seen on film. Dream sequences are another important aspect in this film. In one of them, Kaspar Hauser has dream images of the Sahara desert, for which Herzog used material he shot in the Western Sahara on earlier occasions. I don't know of any other director who used this technique to such avail up until now. One of the most stunning scenes is when the "Man in black" leaves him with the shot on the mountain and soon after the music with the requiem starts. It's almost like a romantic twist on 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Herzog has done a fantastic job recounting the legend of Kaspar Hauser to the screen. The casting of Bruno S. in the role of Kaspar Hauser is of particular interest. He was a street artist in Berlin, when Herzog found him and decided he would be ideal to play the role of Kaspar Hauser. Before this, Bruno S. had a troubled past. After being severely beaten by his mother, he became deaf and was placed in an institution for retarded children at the age of three. At nine, when he tried to escape, he was transferred to a correctional institution. With further escape attempts, he amassed a number of criminal offenses and was incarcerated for more than twenty years. The authenticity of Bruno's performance brings such an element of sincerity to the film, that makes it almost impossible not to root for his cause. Bruno S. also starred in Herzog's STROSZEK (1976).

Camera Obscura --- 10/10

It's a well known philosophical conundrum, would a man be able to think (or even be properly considered a man) if he was denied all sensory stimulation? In Nuremburg in 1828, there was a practical test of this proposition, when a person was discovered in town who had spent all his previous life incarcerated and denied human contact. He was duly taught how to think; but in fact, was not grateful for the experience. Werner Herzog's film examines the strange life of Kaspar Hauser - I find it hard to say whether or not I consider it a good film, because that life itself was so strange. Certainly it better recreated the bafflement of those who interacted with Kaspar than it managed to suggest what it really felt like to be Kaspar - but then, who could know? It's probably not Herzog's greatest achievement - but it's certainly an intriguing subject.

¿Sabías que…?

- TriviaTo perform the scene in which Kaspar learns to walk, actor Bruno S. knelt for three hours with a stick behind his knees until his legs were too numb to stand.

- ErroresIn a brief scene we see a stork eating a frog with its legs tagged (ringed), but bird ringing didn't start until the end of the nineteenth century, decades after the life of Kaspar Hauser.

- Citas

Opening caption: Do you not then hear this horrible scream all around you that people usually call silence.

- Créditos curiososOpening credits prologue: One Sunday in 1828 a ragged boy was found abandoned in the town of N. He could hardly walk and spoke but one sentence.

Later, he told of being locked in a dark cellar from birth. He had never seen another human being, a tree, a house before.

To this day no one knows where he came from - or who set him free.

Don't you hear that horrible screaming all around you? That screaming men call silence?

- ConexionesFeatured in Was ich bin, sind meine Filme (1978)

- Bandas sonorasCanon in D major

Composed by Johann Pachelbel

Selecciones populares

Inicia sesión para calificar y agrega a la lista de videos para obtener recomendaciones personalizadas

- How long is The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser?Con tecnología de Alexa

Detalles

- Fecha de lanzamiento

- País de origen

- Idioma

- También se conoce como

- The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser

- Locaciones de filmación

- Croagh Patrick, Westport, Mayo, Irlanda(archive footage)

- Productoras

- Ver más créditos de la compañía en IMDbPro

Taquilla

- Total a nivel mundial

- USD 3,451

- Tiempo de ejecución1 hora 50 minutos

- Mezcla de sonido

- Relación de aspecto

- 1.66 : 1

Contribuir a esta página

Sugiere una edición o agrega el contenido que falta

Principales brechas de datos

By what name was El enigma de Gaspar Hauser (1974) officially released in India in English?

Responda