Un trabajador del campo convence a la mujer que ama de que se case con su jefe, moribundo y rico, para hacerse con su fortuna.Un trabajador del campo convence a la mujer que ama de que se case con su jefe, moribundo y rico, para hacerse con su fortuna.Un trabajador del campo convence a la mujer que ama de que se case con su jefe, moribundo y rico, para hacerse con su fortuna.

- Dirección

- Guionista

- Elenco

- Ganó 1 premio Óscar

- 13 premios ganados y 13 nominaciones en total

Robert J. Wilke

- The Farm Foreman

- (as Robert Wilke)

Timothy Scott

- Harvest Hand

- (as Tim Scott)

Terrence Malick

- Mill Worker

- (sin créditos)

- Dirección

- Guionista

- Todo el elenco y el equipo

- Producción, taquilla y más en IMDbPro

Opiniones destacadas

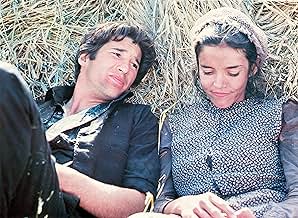

Days of heaven is exactly what this is. The magic hour (when much of the film was shot), those moments before dawn and after dusk when everything is indirect, dreamlike, breathless, heartwaking. There's no real story, as such. Sure, there's a general plot line which should satisfy any casual viewer. This isn't, after all, a hard film to follow. It is simply that the environment is the main character as opposed to the human elements. Linda Manz's young character narrates the story sporadically, like a sleepy traveler beside the campfire telling you of half-forgotten memories, and wonderful, casual observations that will seem clearer in the morning light, but no longer worth mentioning. Her voice is halting and uncertain, belying a personality that is confident in all other respects. Other actors, good (Brooke Adams, Sam Shepard) and not-so-good (Richard Gere) blend in perfectly. Their performances are so understated that you forget they are actors playing characters. Even Richard Gere, who never learned subtlety and would never again employ it, is almost invisible here.

This is not a long film. For all its leisurely pace, ninety-six minutes is all it needs to tell its tale. Terrence Malick is out for sight and sound. There is nothing lost to unneeded expression, nothing not shared in the space in front of you. That leaves cinematographer Néstor Almendros with the freedom to photograph, to observe without opinion whatever seems to be happening most openly before him.

When I first finished watching "Days of Heaven" it felt like waking from a dream. I couldn't be sure how much time has passed. It seemed so long, but the silence was the same, and little had changed outside my window. Nothing but the heavy quiet was all around me, and I felt the desperate desire to move. Everything beneath my feet felt moving, quietly slipping past and all I had to do was put soles to earth and start walking. This is a film of photographs, images of the purest sort. Open your eyes.

This is not a long film. For all its leisurely pace, ninety-six minutes is all it needs to tell its tale. Terrence Malick is out for sight and sound. There is nothing lost to unneeded expression, nothing not shared in the space in front of you. That leaves cinematographer Néstor Almendros with the freedom to photograph, to observe without opinion whatever seems to be happening most openly before him.

When I first finished watching "Days of Heaven" it felt like waking from a dream. I couldn't be sure how much time has passed. It seemed so long, but the silence was the same, and little had changed outside my window. Nothing but the heavy quiet was all around me, and I felt the desperate desire to move. Everything beneath my feet felt moving, quietly slipping past and all I had to do was put soles to earth and start walking. This is a film of photographs, images of the purest sort. Open your eyes.

Oh, I better come out and say it: I love Terrence Malick. I think he's one of the few filmmakers who has completely and utterly captured filmic form. "The Thin Red Line" was, to me, an astonishing experience; beautiful, horrific and the best movie of the 90s. "Badlands" is the best lovers-on-the-lam movie I've ever seen (it certainly makes "True Romance" look like a gimmicky fraud of a movie). Malick somehow manages to make everything seem painfully beautiful: his landscape, his actors, his dialogue. There's something always elegiac about his movies.

There's a picture of James Dean I saw from his youth -- a baseball team photo -- and the caption said something about how it captured his face, and in it, wisdom and sadness far beyond his years. That's what Malick does in his films and particularly in this film.

He must have been a fan of James Dean (probably one of the reasons he chose to make "Badlands," as a sort of homage), but not in the sense that coolness comes from a perfectly combed coiffure, a red leather jacket (which it wasn't -- it was a windbreaker) and a dark brood. There's a similar story here to that of "Giant," set on a farm with that remarkable house, two men and one girl. Only "Giant" didn't have a philosophizing and very strange little girl. It was also an overblown soap opera and while this film is, I guess, a melodrama, it certainly isn't melodramatic.

If Malick is anyone in the film, he's Sam Shapard; watching his love through a lens. Malick uses Manz as a sort of channel. If this is indeed some fashion of his own story, Malick tells us through her, with he visualized by Shepard, which is a somewhat brilliant approach. Manz is strangely philosophical; at once blunt and abstract. The story is obviously centered around her -- I don't see why this wouldn't be obvious -- but she's pushed into the background, commenting on the characters and informing us like God from above.

As always with Malick, his film is mesmerizing and hypnotic. I was surprised that the film was only a little over an hour-and-a-half. The great Ennio Morricone created a wonderful score for this film that seems to forebode impending doom. Unlike his more famous spaghetti western scores, it's never overly-flamboyant. And the cinematography, listed as belonging to Nestor Almendros, but well-known to be at least substantially contributed to by Haskell Wexler, is so much like an oil painting that it's just about liquid film. I'd be willing to pay a lot of money to see this one on the big screen.

It might seem obvious to state that this film is a transition between "Badlands" and "The Thin Red Line," after all it was the middle film. But this film has moments, especially in the finale, that are surprisingly close to that of "Badlands" and this is the film where Malick fully mastered his approach of lush, visual poetry told at a languid pace that never seems boring, since you're fully within the film;s grasp.

Pauline Kael said in her review that "the film is an empty Christmas tree: you can hang all your dumb metaphors on it." And Charles Taylor, always following Kael's lead (even from beyond the grave), said of Malick's two 1970s films, "Next to the work of Altman, Scorsese, Coppola, De Palma and Mazursky from that period, they're pallid jokes."

What never fails to get me furious is when someone viciously attacks a director, like Malick, for being self-indulgent. Of course it's self-indulgent, he's telling a story that means something to him and trying to share what he feels with us. Malick certainly isn't trying to alienate people, and if you are alienated by his films, well, don't watch them. Malick is a filmmaker like Kubrick, but more fluid and much less abrasive. I mean, if you're going to aggressively attack a filmmaker, aggressively attack someone who is aggressive on his side. Directors like Malick use abstractions to engage their audiences more fully than most. By leaving things -- often feelings -- open to interpretation, the film becomes more intimate.

Certainly one of the most enduring films from the 70s, this is a masterwork.

****

There's a picture of James Dean I saw from his youth -- a baseball team photo -- and the caption said something about how it captured his face, and in it, wisdom and sadness far beyond his years. That's what Malick does in his films and particularly in this film.

He must have been a fan of James Dean (probably one of the reasons he chose to make "Badlands," as a sort of homage), but not in the sense that coolness comes from a perfectly combed coiffure, a red leather jacket (which it wasn't -- it was a windbreaker) and a dark brood. There's a similar story here to that of "Giant," set on a farm with that remarkable house, two men and one girl. Only "Giant" didn't have a philosophizing and very strange little girl. It was also an overblown soap opera and while this film is, I guess, a melodrama, it certainly isn't melodramatic.

If Malick is anyone in the film, he's Sam Shapard; watching his love through a lens. Malick uses Manz as a sort of channel. If this is indeed some fashion of his own story, Malick tells us through her, with he visualized by Shepard, which is a somewhat brilliant approach. Manz is strangely philosophical; at once blunt and abstract. The story is obviously centered around her -- I don't see why this wouldn't be obvious -- but she's pushed into the background, commenting on the characters and informing us like God from above.

As always with Malick, his film is mesmerizing and hypnotic. I was surprised that the film was only a little over an hour-and-a-half. The great Ennio Morricone created a wonderful score for this film that seems to forebode impending doom. Unlike his more famous spaghetti western scores, it's never overly-flamboyant. And the cinematography, listed as belonging to Nestor Almendros, but well-known to be at least substantially contributed to by Haskell Wexler, is so much like an oil painting that it's just about liquid film. I'd be willing to pay a lot of money to see this one on the big screen.

It might seem obvious to state that this film is a transition between "Badlands" and "The Thin Red Line," after all it was the middle film. But this film has moments, especially in the finale, that are surprisingly close to that of "Badlands" and this is the film where Malick fully mastered his approach of lush, visual poetry told at a languid pace that never seems boring, since you're fully within the film;s grasp.

Pauline Kael said in her review that "the film is an empty Christmas tree: you can hang all your dumb metaphors on it." And Charles Taylor, always following Kael's lead (even from beyond the grave), said of Malick's two 1970s films, "Next to the work of Altman, Scorsese, Coppola, De Palma and Mazursky from that period, they're pallid jokes."

What never fails to get me furious is when someone viciously attacks a director, like Malick, for being self-indulgent. Of course it's self-indulgent, he's telling a story that means something to him and trying to share what he feels with us. Malick certainly isn't trying to alienate people, and if you are alienated by his films, well, don't watch them. Malick is a filmmaker like Kubrick, but more fluid and much less abrasive. I mean, if you're going to aggressively attack a filmmaker, aggressively attack someone who is aggressive on his side. Directors like Malick use abstractions to engage their audiences more fully than most. By leaving things -- often feelings -- open to interpretation, the film becomes more intimate.

Certainly one of the most enduring films from the 70s, this is a masterwork.

****

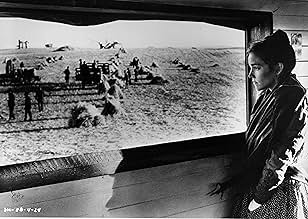

Terrence Malick is less a storyteller than a visual poet. At times, the images in 'Days of Heaven (1978)' seem too beautiful to be believed – could Mother Nature even construct such moments of magnificence at her own accord? Cinematographers Néstor Almendros and Haskell Wexler (credited only as "additional photographer") consistently shot the film during the "magic hour" between darkness and sunrise/sunset, when the sun's radiance is missing from the sky, and so their colours have a muted presence, as though filtered through the stalks of wheat that saturate the landscape. Crucial alongside the film's photographers are composer Ennio Morricone – utilising a variation on the seventh movement ("Aquarium") in Camille Saint-Saëns's "Carnival of the Animals" suite – and a succession of sound editors, whose work brings a dreamy, ethereal edge to the vast fields of the Texas Panhandle. The film's final act, away from the wheat-fields, recalls Arthur Penn's 'Bonnie and Clyde (1967),' but otherwise Malick's style, contemplative and elegiac, is in a class of its own, more comparable perhaps to Kurosawa's 'Dersu Uzala (1975).'

Malick refuses to explore his characters' motivations. The viewer is deliberately kept at an arm's length, and Malick eschews cinema's traditional notions of narrative development. Instead, the story is told as a succession of fleeting moments, the sort that a young girl (the film's narrator, Linda Manz) might pick up through her day-to-day experiences and muted understanding of adult emotions. Note that the girl is always kept separate from the dramatic crux of the film – the love-triangle between Billy, Abby, and the Farmer – and her comprehension of events is tainted by her adolescent grasp on adult relationships and societal norms. I was reminded of Andrew Dominik's recent 'The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007)' {another sumptuously-photographed picture}, which also refused to explore its title character, Jesse James, kept at a distance through the impartial objectivity of the historical narrator. In Malick's film, Linda's narration tells us one thing, and the viewer sees another. But one can never fully understand the complex emotions driving human behaviour, so perhaps the girl's perspective is as good as any other.

'Days of Heaven' derives its title from a passage in the Bible (Deuteronomy 11:21), and Malick's tale of jealousy and desire is suitably Biblical in nature. Essential to this allegory is an apocalyptic plague of locusts, which descend upon the wheat-fields like an army from the heavens. When the fields erupt into flame, quite literally from the broiling emotions of the film's conflicted characters, the viewer is confronted by the most intense manifestation of Hell-on- Earth since the burning village in Bondarchuk's 'War and Peace (1967).' But, interestingly, Malick here regresses on his own allegory: Judgement Day isn't the end, but rather it comes and goes. Life is driven by the inexorable march of Fate: The Farmer (Sam Shepard) is doomed to die within a year; Bill (Richard Gere) is doomed to repeat his mistakes twice over. In the film's final moments, Linda and her newfound friend embark purposelessly along the railway tracks, the tracks being a physical incarnation of Fate itself: their paths are laid down already, but we mortals can never know precisely where they lead until we get there.

Malick refuses to explore his characters' motivations. The viewer is deliberately kept at an arm's length, and Malick eschews cinema's traditional notions of narrative development. Instead, the story is told as a succession of fleeting moments, the sort that a young girl (the film's narrator, Linda Manz) might pick up through her day-to-day experiences and muted understanding of adult emotions. Note that the girl is always kept separate from the dramatic crux of the film – the love-triangle between Billy, Abby, and the Farmer – and her comprehension of events is tainted by her adolescent grasp on adult relationships and societal norms. I was reminded of Andrew Dominik's recent 'The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007)' {another sumptuously-photographed picture}, which also refused to explore its title character, Jesse James, kept at a distance through the impartial objectivity of the historical narrator. In Malick's film, Linda's narration tells us one thing, and the viewer sees another. But one can never fully understand the complex emotions driving human behaviour, so perhaps the girl's perspective is as good as any other.

'Days of Heaven' derives its title from a passage in the Bible (Deuteronomy 11:21), and Malick's tale of jealousy and desire is suitably Biblical in nature. Essential to this allegory is an apocalyptic plague of locusts, which descend upon the wheat-fields like an army from the heavens. When the fields erupt into flame, quite literally from the broiling emotions of the film's conflicted characters, the viewer is confronted by the most intense manifestation of Hell-on- Earth since the burning village in Bondarchuk's 'War and Peace (1967).' But, interestingly, Malick here regresses on his own allegory: Judgement Day isn't the end, but rather it comes and goes. Life is driven by the inexorable march of Fate: The Farmer (Sam Shepard) is doomed to die within a year; Bill (Richard Gere) is doomed to repeat his mistakes twice over. In the film's final moments, Linda and her newfound friend embark purposelessly along the railway tracks, the tracks being a physical incarnation of Fate itself: their paths are laid down already, but we mortals can never know precisely where they lead until we get there.

This is gorgeous looking film very much filmed at dusk and dawn. A film misunderstood upon its time of release and only after Terrence Malick's subsequent films can you now understand what the writer- director was aiming at.

The fact that Malick's next film emerged 20 years later we understand this is a person who wants to tell his story by visuals. Actors talking is just secondary and those scenes end up on the cutting room floor.

Days of Heaven which was shot in 70mm always had a reputation for its Cinematography which won an Oscar.

Now we can marvel at it in our homes on widescreen high definition television. You can really have those close ups of those insects. It is also a surprisingly short film, coming in at just over 90 minutes.

The tale is slight, Gere is a hothead with a girlfriend that is pretending to be his sister and his actual younger sister. They get a job whilst fleeing from Chicago in a farm in Texas where the Farmer played by Sam Shepard takes a shine to the girlfriend and marries her. Gere is aware that the Framer only has a year to live.

Apparently the film took several years to be edited and the narration from the youngest sister had to be added to make the story flow. A similar device was used by Malick in 'The Thin Red Line.'

The film might be seen as slow and maybe hard to fathom because there is relative little dialogue but as mentioned you admire the visuals and at 90 minutes it is not as slow moving as you think.

A brave beautifully crafted film.

The fact that Malick's next film emerged 20 years later we understand this is a person who wants to tell his story by visuals. Actors talking is just secondary and those scenes end up on the cutting room floor.

Days of Heaven which was shot in 70mm always had a reputation for its Cinematography which won an Oscar.

Now we can marvel at it in our homes on widescreen high definition television. You can really have those close ups of those insects. It is also a surprisingly short film, coming in at just over 90 minutes.

The tale is slight, Gere is a hothead with a girlfriend that is pretending to be his sister and his actual younger sister. They get a job whilst fleeing from Chicago in a farm in Texas where the Farmer played by Sam Shepard takes a shine to the girlfriend and marries her. Gere is aware that the Framer only has a year to live.

Apparently the film took several years to be edited and the narration from the youngest sister had to be added to make the story flow. A similar device was used by Malick in 'The Thin Red Line.'

The film might be seen as slow and maybe hard to fathom because there is relative little dialogue but as mentioned you admire the visuals and at 90 minutes it is not as slow moving as you think.

A brave beautifully crafted film.

10katsat

If any movie could be called filmed poetry, this would be it. From its first opening shot to its last frame, there is such lyricism and emotion and beauty that it almost leaves you speechless. I have not seen this movie in years, but it still affects me and I want to write about it. There is a pervading sadness to the movie, like a memory of something wonderful that could have been, that should have been, that almost was, and is all the more tragic because it was in your hands but slipped through your fingers. This is not a movie for everyone, but if you believe that film can be one of the highest forms of art, this is the film to see.

¿Sabías que…?

- TriviaThe shot of locusts ascending to the sky was shot in reverse with the helicopter crew throwing peanut shells down, and actors walking backwards.

- ErroresTowards the end of the movie, Bill fires three shots from a double-barreled shotgun without reloading.

- Bandas sonorasEnderlin

Written and Performed by Leo Kottke

Used by permission of Overdrive Music A.S.C.A.P. Copyright 1978

Selecciones populares

Inicia sesión para calificar y agrega a la lista de videos para obtener recomendaciones personalizadas

- How long is Days of Heaven?Con tecnología de Alexa

Detalles

- Fecha de lanzamiento

- País de origen

- Idiomas

- También se conoce como

- Days of Heaven

- Locaciones de filmación

- Lethbridge, Alberta, Canadá(Lethbridge Viaduct High Level Railroad Bridge)

- Productora

- Ver más créditos de la compañía en IMDbPro

Taquilla

- Presupuesto

- USD 3,000,000 (estimado)

- Total en EE. UU. y Canadá

- USD 3,446,749

- Total a nivel mundial

- USD 3,492,909

- Tiempo de ejecución1 hora 34 minutos

- Color

- Relación de aspecto

- 1.85 : 1

Contribuir a esta página

Sugiere una edición o agrega el contenido que falta