CALIFICACIÓN DE IMDb

7.7/10

13 k

TU CALIFICACIÓN

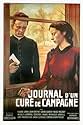

Un joven sacerdote intenta cumplir con sus funciones a pesar de un misterioso dolor de estómago.Un joven sacerdote intenta cumplir con sus funciones a pesar de un misterioso dolor de estómago.Un joven sacerdote intenta cumplir con sus funciones a pesar de un misterioso dolor de estómago.

- Dirección

- Guionistas

- Elenco

- Nominada a1 premio BAFTA

- 7 premios ganados y 3 nominaciones en total

Adrien Borel

- Priest of Torcy (Curé de Torcy)

- (as Andre Guibert)

Rachel Bérendt

- Countess (La Comtesse)

- (as Marie-Monique Arkell)

Antoine Balpêtré

- Dr. Delbende (Docteur Delbende)

- (as Balpetre)

Gaston Séverin

- Canon (Le Chanoine)

- (as Gaston Severin)

Serge Bento

- Mitonnet

- (as Serge Benneteau)

Germaine Stainval

- La patronne du café

- (sin créditos)

François Valorbe

- Bit Role

- (sin créditos)

- Dirección

- Guionistas

- Todo el elenco y el equipo

- Producción, taquilla y más en IMDbPro

Opiniones destacadas

10coop-16

That simple quote from Bresson's film sums up its teaching-and Bresson's achievement..In another review, I referred to this film as one of the handful of "elevens' in the history of film, the two or three dozen that cling to the soul forever.With absolute simplicity and unrivaled economy of means, Bresson has created one of the few 'religious experiences' in the history of cinema.SEE IT.

*Diary of a Country Priest* is a nearly perfect film. Made in 1950, this film benefits from Bresson being at the height of his powers. As he aged, the slow, measured, static style became more and more mannered, or more and more intolerable, shall we say. But here he doesn't go overboard: the mood is portentous rather than pretentious. And in any case, it's not as slow as you may think: there are probably hundreds of cuts in the film (this ain't no Carl Th. Dreyer movie). Along those lines, Bresson's method of adaptation -- which is to distill the ESSENCE of the chosen work -- is stringently economical and pared to the bone. In other words, the thing doesn't simply dawdle along. Based on a 1930's novel by a right-wing Euro novelist, *Diary* details the sad experiences of a young priest with health problems who is assigned to a new parish. The villagers treat the young man with hostility and downright scorn. Sensing and resenting the new priest's obvious holiness (everybody hates a saint), they ridicule him, shut him out of their confidences, send threatening anonymous notes ("I feel sorry for you, but GET OUT") . . . to all of which our hero responds with a sort of confused empathy. Meanwhile, Bresson uses a striking narrative device: we see the priest writing in his diary, while VOICING OVER what he's writing, and then there's a cut to a scene which SHOWS the action the priest has just been writing (and narrating) about. This complex, layered style proves to be more than a fair trade-off for the paucity of actual narrative incidents. We're invited to ponder an event's significance -- a lucky thing, because the action is quite often so psychologically complex that we need room to breathe, to think things over. Don't presume to form an opinion of *Diary* until you've seen it at least twice. Sounds like homework, I know, but so does *King Lear*. Great art IS homework.

Perhaps the film's true value is its delineation of just how stagnant and unpleasant little towns can be. Again Bresson is inventive: rather than simply show us the putrid little village, the director instead opts for an oblique approach, inviting us to IMAGINE just how putrid the village actually is, usually by heightening off-screen sound effects. Quite often, we hear unpleasant things like motorcycles backfiring, rakes running over asphalt, crows screeching, mean-spirited giggling outside a window, iron gates slamming shut, and so on.

And finally, it must be said that it's surprising how avowed agnostic directors make the most persuasive religious movies. In my view, this film and Dreyer's *Ordet* remain the greatest films about Christianity in the history of cinema (the conversion scene in the middle of *Diary* might prompt you to go to church next Sunday). Anyway, *Diary of a Country Priest* is an unassailable, influential masterpiece that's a MUST-OWN for the true cineaste, and a possible education in art for everybody else. Get the new Criterion edition, watch it twice, and listen to Peter Cowie's commentary. I assure you that it won't be a waste of your time.

Perhaps the film's true value is its delineation of just how stagnant and unpleasant little towns can be. Again Bresson is inventive: rather than simply show us the putrid little village, the director instead opts for an oblique approach, inviting us to IMAGINE just how putrid the village actually is, usually by heightening off-screen sound effects. Quite often, we hear unpleasant things like motorcycles backfiring, rakes running over asphalt, crows screeching, mean-spirited giggling outside a window, iron gates slamming shut, and so on.

And finally, it must be said that it's surprising how avowed agnostic directors make the most persuasive religious movies. In my view, this film and Dreyer's *Ordet* remain the greatest films about Christianity in the history of cinema (the conversion scene in the middle of *Diary* might prompt you to go to church next Sunday). Anyway, *Diary of a Country Priest* is an unassailable, influential masterpiece that's a MUST-OWN for the true cineaste, and a possible education in art for everybody else. Get the new Criterion edition, watch it twice, and listen to Peter Cowie's commentary. I assure you that it won't be a waste of your time.

This is adapted from a book apparently but seems to be very much a personal diary. A pious young priest, I take this to be Bresson himself, arrives at a remote village during the war. He's idealistic and wants to be of help, is eager to knock on doors and upset normalcy.

The very first line on his diary, he writes on it throughout, delineates a whole worldview here; absolute frankness, the most insignificant secrets of life, life without a trace of mystery, laid bare.

His intense sincerity is curious to those around him, a local churchman wonders with disapproval if he's not better off becoming a monk, this is a peoples job he says implying people just want to go on as they do with the small of life, not be upset in how they rationalize what they do.

And this is all so we can find ahead of us a life that retains its confounding mystery, a mystery that conceals hurt. A mother who has been so numbed by the loss of a child she turns a blind eye to suffering in her home. Two girls, both in unhappy homes, one smitten by him, the other comes to revile him because he preaches resignation and she's burning up with a desire to run off from an unhappy life.

There are several good things here. But I hit a stumbling block as a viewer in the philosophy behind it, I take this to be Bresson's; anguish as deep truth, obstinacy as spiritual fortitude, renounciation of life but his kind only imparts gloom and dejection.

This is all crude to me. For example the priest has a letter that would exonerate him from a certain wrongdoing being rumored but says nothing about it, the silence gives him strength. But, if we're here to take care of life and lead a way out of suffering, that means taking care of our own selves as well and doing everything we can to dispel illusion. This is just needless ego as purity; how is anyone better off not knowing that she really died in peace?

It's all essentially coming from Christian notions of grace where the body has to be mortified, the soul atone for sin by dejection, and the resulting anguish as proof of being close to the truth and price paid for it. This is all baggage for me, a romanticism of suffering in place of clear seeing. I know of a more eloquent "resignation" (which he preaches) in Buddhist non-attachment; a cessation of ego that doesn't demand self-mortification.

Another possible reading is too tantalizing to ignore but would go against the grain of why the film is lauded as pure and deep.

We see a young man who is well-meaning but a little befuddled in his efforts to be pure; he drives himself to sickness by his ascetic lifestyle and begins gradually to confuse the pain of that sickness with a pious torment of the soul in the course of doing the right thing, a surrogate Christ bearing the sins of mankind. It's only too late that he comes to recognize that love is all, awakened by how it has been wasted in his old classmate's home (a cynical, self- absorbed version of his intellectual self).

Maybe this was early for Bresson; I find this to be purism that is still beholden to self and preconceived ideas. Maybe his next films shed some light.

The very first line on his diary, he writes on it throughout, delineates a whole worldview here; absolute frankness, the most insignificant secrets of life, life without a trace of mystery, laid bare.

His intense sincerity is curious to those around him, a local churchman wonders with disapproval if he's not better off becoming a monk, this is a peoples job he says implying people just want to go on as they do with the small of life, not be upset in how they rationalize what they do.

And this is all so we can find ahead of us a life that retains its confounding mystery, a mystery that conceals hurt. A mother who has been so numbed by the loss of a child she turns a blind eye to suffering in her home. Two girls, both in unhappy homes, one smitten by him, the other comes to revile him because he preaches resignation and she's burning up with a desire to run off from an unhappy life.

There are several good things here. But I hit a stumbling block as a viewer in the philosophy behind it, I take this to be Bresson's; anguish as deep truth, obstinacy as spiritual fortitude, renounciation of life but his kind only imparts gloom and dejection.

This is all crude to me. For example the priest has a letter that would exonerate him from a certain wrongdoing being rumored but says nothing about it, the silence gives him strength. But, if we're here to take care of life and lead a way out of suffering, that means taking care of our own selves as well and doing everything we can to dispel illusion. This is just needless ego as purity; how is anyone better off not knowing that she really died in peace?

It's all essentially coming from Christian notions of grace where the body has to be mortified, the soul atone for sin by dejection, and the resulting anguish as proof of being close to the truth and price paid for it. This is all baggage for me, a romanticism of suffering in place of clear seeing. I know of a more eloquent "resignation" (which he preaches) in Buddhist non-attachment; a cessation of ego that doesn't demand self-mortification.

Another possible reading is too tantalizing to ignore but would go against the grain of why the film is lauded as pure and deep.

We see a young man who is well-meaning but a little befuddled in his efforts to be pure; he drives himself to sickness by his ascetic lifestyle and begins gradually to confuse the pain of that sickness with a pious torment of the soul in the course of doing the right thing, a surrogate Christ bearing the sins of mankind. It's only too late that he comes to recognize that love is all, awakened by how it has been wasted in his old classmate's home (a cynical, self- absorbed version of his intellectual self).

Maybe this was early for Bresson; I find this to be purism that is still beholden to self and preconceived ideas. Maybe his next films shed some light.

Journal d'un cure de Campagne is about a young priest who, whilst suffering from an illness, is assigned to a new parish in a French country village. The story is told by the priests recounting of his experiences in his diary. This itself is a powerful narrative device, as we not only understand the experiences of the protagonist, but also how he reflects upon them with hindsight, relating his observations to faith and human nature. As he carries out his duties in his new parish though, he is treated with animosity and hatred by many of the villiagers, because they see him as an unwanted intrusion into their lives. As he becomes estranged, and to an extend outcast by the townspeople, he increasingly relies on his faith for strength and comfort, however even this begins to fade as he witnesses the townspeople purvey sinful and malicous behaviour, damaging his faith in human nature.

The films of Robert Bresson, although wonderful, can at times seem austere almost to the point of being drained of any emotion. Before passing judgement though, it is important to understand his aims and understanding of film making. Bresson believed that the theatrical performing of actors had no place in cinema, and so typically cast non-actors for his films. The reason for his desire to suppress performing, was to avoid the melodramatic histrionics common with conventional acting as he believed it shortchanges the complexities of human emotion that in real life are much more subtle and not always on the surface. A large part of who we are he believed, is determined by experience, circumstance and environment. These elements affect the way we 'perform' and obscure who we are at the core essence of our being. Bresson was much more concerned with this person, whom we are when all our affectations are removed and we are laid bare. In Diary of a Country Priest, Bresson had Claude Laydu repeat scenes many times in order so that he would rid himself of all natural desire to perform. This suppressed emotion re-introduces the intricately nuanced expression, replacing the scenes with a delicate and contemplative lilt. Like Ozu, another master of character expression and portrayal, Bresson proves that by adopting this method in conjunction with his wonderful compositions, it forces the viewer to replace the lack of gratuitous emotion with their own feelings, resulting in moments of genuine pathos and emotion.

The films of Robert Bresson, although wonderful, can at times seem austere almost to the point of being drained of any emotion. Before passing judgement though, it is important to understand his aims and understanding of film making. Bresson believed that the theatrical performing of actors had no place in cinema, and so typically cast non-actors for his films. The reason for his desire to suppress performing, was to avoid the melodramatic histrionics common with conventional acting as he believed it shortchanges the complexities of human emotion that in real life are much more subtle and not always on the surface. A large part of who we are he believed, is determined by experience, circumstance and environment. These elements affect the way we 'perform' and obscure who we are at the core essence of our being. Bresson was much more concerned with this person, whom we are when all our affectations are removed and we are laid bare. In Diary of a Country Priest, Bresson had Claude Laydu repeat scenes many times in order so that he would rid himself of all natural desire to perform. This suppressed emotion re-introduces the intricately nuanced expression, replacing the scenes with a delicate and contemplative lilt. Like Ozu, another master of character expression and portrayal, Bresson proves that by adopting this method in conjunction with his wonderful compositions, it forces the viewer to replace the lack of gratuitous emotion with their own feelings, resulting in moments of genuine pathos and emotion.

This story was very influential and moving in many ways, seeing the afflictions of the Priest and the way that he deals with the animosity of his town are truly interesting. It depicts, very well, the life of a young man (who appears very boyish throughout the entirety of the film) not just living as a Priest, but also living as a sort of outcast -- it shows very well what the inter-workings of this Priest's, this outcast's brain is like, and it shows the human emotionality very well.

From the beginning to the end of the film I was fascinated with the main character, and his goals and his aims, his beliefs and his passionate inclination to helping others -- rarely do you see such great work done in putting the spotlight on the character. Bresson truly shows himself to be a master of character depiction. Anyone who has ever experienced awkward social circumstances or has ever felt alienated can immediately relate to the Father.

I found the dialogue in this film to be at times absolutely shocking & amazing, and the actors to be filled with a lot of feeling; there are parts in this film that I will remember forever because of the fabulous writing and acting. You rarely see a film with as much poignant & sharp character interaction as this; I found myself always anticipating the next meeting that the Father would have with certain characters, always anticipating more of the amazing dialogue.

For those who are interested in religion, this film really hits the nail on the head. I feel that, although it is very much inclined towards Christianity and Christian thought, it was in no way overbearing and nor would it take away from the film for a non-Christian. In fact, what makes the dialogue so sharp is the debates and self-doubt that we see the Priest have from time to time. Overall, a terrific film and study of social relationships.

From the beginning to the end of the film I was fascinated with the main character, and his goals and his aims, his beliefs and his passionate inclination to helping others -- rarely do you see such great work done in putting the spotlight on the character. Bresson truly shows himself to be a master of character depiction. Anyone who has ever experienced awkward social circumstances or has ever felt alienated can immediately relate to the Father.

I found the dialogue in this film to be at times absolutely shocking & amazing, and the actors to be filled with a lot of feeling; there are parts in this film that I will remember forever because of the fabulous writing and acting. You rarely see a film with as much poignant & sharp character interaction as this; I found myself always anticipating the next meeting that the Father would have with certain characters, always anticipating more of the amazing dialogue.

For those who are interested in religion, this film really hits the nail on the head. I feel that, although it is very much inclined towards Christianity and Christian thought, it was in no way overbearing and nor would it take away from the film for a non-Christian. In fact, what makes the dialogue so sharp is the debates and self-doubt that we see the Priest have from time to time. Overall, a terrific film and study of social relationships.

¿Sabías que…?

- TriviaThe hand and handwriting in the film belong to Robert Bresson.

- Citas

[subtitled version]

Countess: Love is stronger than death. Your scriptures say so.

Curé d'Ambricourt: We did not invent love. It has its order, its law.

Countess: God is its master.

Curé d'Ambricourt: He is not the master of love. He is love itself. If you would love, don't place yourself beyond love's reach.

- ConexionesFeatured in Histoire(s) du cinéma: Les signes parmi nous (1999)

Selecciones populares

Inicia sesión para calificar y agrega a la lista de videos para obtener recomendaciones personalizadas

- How long is Diary of a Country Priest?Con tecnología de Alexa

Detalles

Taquilla

- Total en EE. UU. y Canadá

- USD 47,000

- Fin de semana de estreno en EE. UU. y Canadá

- USD 7,674

- 27 feb 2011

- Total a nivel mundial

- USD 47,000

- Tiempo de ejecución

- 1h 55min(115 min)

- Color

- Relación de aspecto

- 1.37 : 1

Contribuir a esta página

Sugiere una edición o agrega el contenido que falta