CALIFICACIÓN DE IMDb

8.0/10

16 k

TU CALIFICACIÓN

El portero de un edificio se encuentra ante la burla de sus amigos tras ser despedido de su trabajo en un hotel de alto lujo.El portero de un edificio se encuentra ante la burla de sus amigos tras ser despedido de su trabajo en un hotel de alto lujo.El portero de un edificio se encuentra ante la burla de sus amigos tras ser despedido de su trabajo en un hotel de alto lujo.

- Dirección

- Guionista

- Elenco

- Premios

- 2 premios ganados en total

O.E. Hasse

- Small Role

- (sin créditos)

Harald Madsen

- Wedding Musician

- (sin créditos)

Neumann-Schüler

- Small Role

- (sin créditos)

Carl Schenstrøm

- Wedding Musician

- (sin créditos)

Erich Schönfelder

- Small role

- (sin créditos)

- Dirección

- Guionista

- Todo el elenco y el equipo

- Producción, taquilla y más en IMDbPro

Opiniones destacadas

I just viewed this film on the pristine Kino video release, having seen a poorish print years ago.

One of the great classics of the German silent cinema, hugely influential, this true work of art not only displays the seemingly limitless resources of the UFA studios, but dares to break constantly with convention, particularly by being a "pure" film and dispensing with intertitles, but most spectacularly in its use of the "subjective" camera--creating as far as I know, the first sustained use of "point of view" in the history of movies, which had hitherto shown us action objectively, as it were: the spectator had always merely "observed," as in a third person narrative. Even Griffith and Bitzer's trucking shots, while including "us" in the action, did not represent another character's point of view. Well, after "the Last Laugh," P.O.V. turns up again and again. (See Abel Gance's "Napoleon.") Today the technique is common (necessary!). The most famous shots in "Der Letzte Mann" include the drunken swaying of the room seen through the Doorman's bleary eyes (cinematographer Karl Freund seated in a large swing and pushed back and forth); the opening shot coming down into the lobby by elevator and exiting the gate; and the astonishing vision of the hotel toppling in slow motion over on the poor doorman after his demotion. And can you believe that first night cityscape with the driving rain was all constructed and shot INDOORS?

However, I must say there is an unfortunate message in this drama, that of the merciless German stereotype: fawning before authority and deriding weakness--humiliating the powerless, admiring, almost worshiping the powerful. This is shown by the doorman's vanity and puffed-up self-image, which hinges, it seems, on a splendid uniform and the deference it alone inspires. Position is everything to him, his family, employers, hotel guests and neighbors. This is a shallow world, indeed, a social mentality that I can imagine, without straining too much, easily leading in a few brief years straight to the all-too-successful Gestapo! (I would add that the ending seems to contradict this, but the ending must be discounted; it is a sheer fantasy, "tacked on," really unrelated to the rest of the film and completely out of character.)

One of the great classics of the German silent cinema, hugely influential, this true work of art not only displays the seemingly limitless resources of the UFA studios, but dares to break constantly with convention, particularly by being a "pure" film and dispensing with intertitles, but most spectacularly in its use of the "subjective" camera--creating as far as I know, the first sustained use of "point of view" in the history of movies, which had hitherto shown us action objectively, as it were: the spectator had always merely "observed," as in a third person narrative. Even Griffith and Bitzer's trucking shots, while including "us" in the action, did not represent another character's point of view. Well, after "the Last Laugh," P.O.V. turns up again and again. (See Abel Gance's "Napoleon.") Today the technique is common (necessary!). The most famous shots in "Der Letzte Mann" include the drunken swaying of the room seen through the Doorman's bleary eyes (cinematographer Karl Freund seated in a large swing and pushed back and forth); the opening shot coming down into the lobby by elevator and exiting the gate; and the astonishing vision of the hotel toppling in slow motion over on the poor doorman after his demotion. And can you believe that first night cityscape with the driving rain was all constructed and shot INDOORS?

However, I must say there is an unfortunate message in this drama, that of the merciless German stereotype: fawning before authority and deriding weakness--humiliating the powerless, admiring, almost worshiping the powerful. This is shown by the doorman's vanity and puffed-up self-image, which hinges, it seems, on a splendid uniform and the deference it alone inspires. Position is everything to him, his family, employers, hotel guests and neighbors. This is a shallow world, indeed, a social mentality that I can imagine, without straining too much, easily leading in a few brief years straight to the all-too-successful Gestapo! (I would add that the ending seems to contradict this, but the ending must be discounted; it is a sheer fantasy, "tacked on," really unrelated to the rest of the film and completely out of character.)

F.W Murnau is best known for his expressionistic horror movies, such as 'Nosferatu' and the excellent 'Faust'. This movie is somewhat different from those, as it's a more personal and down to earth sort of tale. Still, despite this not being a member of the horror genre; Murnau's style still allows for much of the great visuals that made his horror movies great. The story itself has definite horror elements, which although they don't involve vampires or the devil; are arguably more frightening, as it dictates and event that could well happen to anyone. The film tackles the idea of 'downfall', and as the prologue states; one can be a prince one day, but what is he tomorrow? This tale is told through the story of a hotel porter that has worked hard all his life but loses his job through incredible bad luck when the manager catches him taking a break. Heartbroken and humiliated, our hero is offered another job; but it only allows for his humiliation to continue, as the job is that of a lowly bathroom attendant. We then follow his struggle as he comes to terms with his loss and the reaction of his family and neighbours.

F.W. Murnau uses no story cards for this silent film, which shows his flair for storytelling. Imagining some of today's 'great' filmmakers telling a story without dialogue is preposterous, but Murnau shows his prowess by doing just that, and doing it down to a fine art. People often cite 'Citizen Kane' for being the film that took storytelling to the next level, and although it did do that; surely some of the credit has to go to F.W. Murnau. This film features what is perhaps the first ever fantasy sequence, a sequence that is, of course, a favourite of today's cinema. Murnau's technical mastery is also shown in many other sequences, including one in particular that sees a scene appear in the middle of a letter. It's quite unbelievable that this was made over eighty years ago, just due to the amazing work on show in the film.

The film falls down a bit towards the end, because of an ill-advised twist. This was put upon F.W. Murnau by the studio releasing the film, who wanted a happy ending. This is just another example of a studio spoiling a great movie, and even before I saw that piece of information in the trivia section for this movie; it was evident to me that it isn't the way that Murnau wanted to take the story from the way it almost appeared to be tacked on to the end of the film. Still, the hour and ten minutes running up the ending are almost as good as silent cinema gets, and in spite of the studio's best efforts to ruin it; The Last Laugh stands tall as on of Murnau's finest films.

F.W. Murnau uses no story cards for this silent film, which shows his flair for storytelling. Imagining some of today's 'great' filmmakers telling a story without dialogue is preposterous, but Murnau shows his prowess by doing just that, and doing it down to a fine art. People often cite 'Citizen Kane' for being the film that took storytelling to the next level, and although it did do that; surely some of the credit has to go to F.W. Murnau. This film features what is perhaps the first ever fantasy sequence, a sequence that is, of course, a favourite of today's cinema. Murnau's technical mastery is also shown in many other sequences, including one in particular that sees a scene appear in the middle of a letter. It's quite unbelievable that this was made over eighty years ago, just due to the amazing work on show in the film.

The film falls down a bit towards the end, because of an ill-advised twist. This was put upon F.W. Murnau by the studio releasing the film, who wanted a happy ending. This is just another example of a studio spoiling a great movie, and even before I saw that piece of information in the trivia section for this movie; it was evident to me that it isn't the way that Murnau wanted to take the story from the way it almost appeared to be tacked on to the end of the film. Still, the hour and ten minutes running up the ending are almost as good as silent cinema gets, and in spite of the studio's best efforts to ruin it; The Last Laugh stands tall as on of Murnau's finest films.

Warning - Possible spoilers lie within.

This is the first silent movie I have watched in its entirety, having previously found myself becoming restless and distracted, I normally find them quite difficult to watch. I came across the Criterion edition of the movie in a large collection of Laserdiscs that I purchased recently, and decided to give it a try. I was speechless.

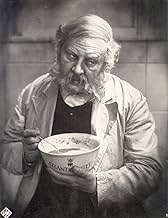

'The Last Laugh' (or 'The Last Man', as its translation would lead you to believe, is a touching story from director F.W. Murnau about an un-named Hotel Porter & Doorman (played excellently by Emil Jannings) who, through no fault of his own, is demoted to Lavatory attendant, and we hereby watch as his life collapses around him. It's an incredibly emotional story - during his downfall, as his friends and family mock him, Jannings' depressed, hunched-over figure can be painfully sad to watch. I found myself filling up in the scene when he finally hands his beloved porter's uniform over to the night watchman.

A landmark in the era of silent films, Murnau used some very clever camera tricks (such as smearing vaseline on the camera lens for 'dream' sequences). It was also one of the first films to use a completely free moving camera with no tripod, testimony to the success of this can be seen immediately in the first scene as the film starts. There are also no title cards in the film. Nor are they needed - The story is carried perfectly by the actors and on no occasion do you feel that you don't know what is going on.

I won't give anything away here, but there are some people that may feel the ending is a little out of place - However, I had grown so fond on Jannings' character that in a way, I was relieved to see the film move on from the final scene where he is sat hunched on the seat in the washroom - and for him to finally have 'The Last Laugh' so to speak :o)

If you have any interest in old cinema, and have not seen this, or just fancy a change from all of the samey Hollywood flicks being churned out right now, I suggest you hunt out a copy right away. Highly recommended.

This is the first silent movie I have watched in its entirety, having previously found myself becoming restless and distracted, I normally find them quite difficult to watch. I came across the Criterion edition of the movie in a large collection of Laserdiscs that I purchased recently, and decided to give it a try. I was speechless.

'The Last Laugh' (or 'The Last Man', as its translation would lead you to believe, is a touching story from director F.W. Murnau about an un-named Hotel Porter & Doorman (played excellently by Emil Jannings) who, through no fault of his own, is demoted to Lavatory attendant, and we hereby watch as his life collapses around him. It's an incredibly emotional story - during his downfall, as his friends and family mock him, Jannings' depressed, hunched-over figure can be painfully sad to watch. I found myself filling up in the scene when he finally hands his beloved porter's uniform over to the night watchman.

A landmark in the era of silent films, Murnau used some very clever camera tricks (such as smearing vaseline on the camera lens for 'dream' sequences). It was also one of the first films to use a completely free moving camera with no tripod, testimony to the success of this can be seen immediately in the first scene as the film starts. There are also no title cards in the film. Nor are they needed - The story is carried perfectly by the actors and on no occasion do you feel that you don't know what is going on.

I won't give anything away here, but there are some people that may feel the ending is a little out of place - However, I had grown so fond on Jannings' character that in a way, I was relieved to see the film move on from the final scene where he is sat hunched on the seat in the washroom - and for him to finally have 'The Last Laugh' so to speak :o)

If you have any interest in old cinema, and have not seen this, or just fancy a change from all of the samey Hollywood flicks being churned out right now, I suggest you hunt out a copy right away. Highly recommended.

People seem compelled to speak in superlative-terms when talking about the great directors; which film is their greatest, which ones are underrated, etc. But this is a film so simple in its themes, so modest in its methods, that it doesn't lend itself to these labels very easily.

"Nosferatu" was revolutionary, but based on intensity, something that doesn't age very well. Other directors took up this notion of visual intensity (Leni, Boese) but structuralized it, and created the real German Horror masterpieces ("Waxworks," "Golem"). Murnau's discovery came later, with this film. That film narrative wasn't something that you followed linearly, but something you become immersed in. The lack of title-cards is not a gimmick, but a conscious decision not to interrupt the flow of this immersion. Reading is rational (hearing, slightly less so) and prevents this from taking place.

Add a Gogolian tale of aging and dignity, and Murnau makes magic. This is what "touching" and "moving" films should be like.

4 out of 5 - An excellent film

"Nosferatu" was revolutionary, but based on intensity, something that doesn't age very well. Other directors took up this notion of visual intensity (Leni, Boese) but structuralized it, and created the real German Horror masterpieces ("Waxworks," "Golem"). Murnau's discovery came later, with this film. That film narrative wasn't something that you followed linearly, but something you become immersed in. The lack of title-cards is not a gimmick, but a conscious decision not to interrupt the flow of this immersion. Reading is rational (hearing, slightly less so) and prevents this from taking place.

Add a Gogolian tale of aging and dignity, and Murnau makes magic. This is what "touching" and "moving" films should be like.

4 out of 5 - An excellent film

F. W Murnau works are rare things - he made very few compared to other directors of his day, and many of those he did make have been lost. The reason he made so few can perhaps be understood by watching The Last Laugh. Like Chaplin, Kubrick and Leone, the effort that went into a single picture was the same effort another director might spread across ten. Nosferatu, his famous Dracula story, is great, and i hear his Faust and Sunrise are also things to behold - but many regard "The Last Laugh" as his masterwork, and also one of the greatest movies of all time. Lillian Gish once said that she never approved of the talkies - she felt that silents were starting to create a whole new art form. She was right, but the proof of this can not be seen in the work of Griffith, who was her frequent collaborator, and who she probably was thinking about when she made this statement - but in the work of German director F. W Murnau.

D. W Griffith is usually shunned for his stance on racial issues and praised for his abilities as an influential film artist. I believe he doesn't deserve this praise - and this movie is why. Not only was Griffith about as subtle as a migraine, but watching a Griffith silent, you get more words than images. There's a title card telling you what is about to happen in every image before it does. The images themselves are almost unnecessary - his style is more literary than cinematic. The difference between watching Griffith's Intolerance and watching F. W Murnau's The Last Laugh is like the difference between watching a silent comedy by Hal Roach and one by Charlie Chaplin. The latter of each pair (Murnau and Chaplin) were visualists and artists, using few words, constructing beauty and high emotion through seemingly simple situations (a tramp who discovers a lost child, or a hotel doorman who loses his job, which is the basis of The Last Laugh).

Silent directors strove to and were praised for their ability to tell stories through images alone, as much as possible, and this is one of the reasons silent cinema reached its pinnacle in F. W Murnau's The Last Laugh - which tells the story of a proud hotel doorman (Emil Jennings), who, after many years of service, is demoted from his position to a mens' bathroom attendant. Murnau tells an incredibly sensitive and human tale, showing how much the job meant to him by having him go to work instead of going to his daughter's wedding. He shows how the position made him respected in his neighbourhood, and how he could not face the neighbourhood without his doorman's uniform. And he tells the story almost entirely through images.

There are no title cards telling us what the images are - they are allowed to speak for themselves. The few words used are worked in through letters and signs. Many silent directors cheated and used title cards to explain the images, but only in this movie did the art form of silent movies, which Lillian Gish refers to, take shape.

I was amazed at the level of depth and emotional complexity that Murnau was capable of conveying without resorting to title cards (or their equivalent in talkies, the voice-over). This movie is also notable for its brilliant use of expressionism, and the first brilliant use of a tracking shot. In Murnau's The Last Laugh, silent movies metaphorically were given movement, and learned to run.

D. W Griffith is usually shunned for his stance on racial issues and praised for his abilities as an influential film artist. I believe he doesn't deserve this praise - and this movie is why. Not only was Griffith about as subtle as a migraine, but watching a Griffith silent, you get more words than images. There's a title card telling you what is about to happen in every image before it does. The images themselves are almost unnecessary - his style is more literary than cinematic. The difference between watching Griffith's Intolerance and watching F. W Murnau's The Last Laugh is like the difference between watching a silent comedy by Hal Roach and one by Charlie Chaplin. The latter of each pair (Murnau and Chaplin) were visualists and artists, using few words, constructing beauty and high emotion through seemingly simple situations (a tramp who discovers a lost child, or a hotel doorman who loses his job, which is the basis of The Last Laugh).

Silent directors strove to and were praised for their ability to tell stories through images alone, as much as possible, and this is one of the reasons silent cinema reached its pinnacle in F. W Murnau's The Last Laugh - which tells the story of a proud hotel doorman (Emil Jennings), who, after many years of service, is demoted from his position to a mens' bathroom attendant. Murnau tells an incredibly sensitive and human tale, showing how much the job meant to him by having him go to work instead of going to his daughter's wedding. He shows how the position made him respected in his neighbourhood, and how he could not face the neighbourhood without his doorman's uniform. And he tells the story almost entirely through images.

There are no title cards telling us what the images are - they are allowed to speak for themselves. The few words used are worked in through letters and signs. Many silent directors cheated and used title cards to explain the images, but only in this movie did the art form of silent movies, which Lillian Gish refers to, take shape.

I was amazed at the level of depth and emotional complexity that Murnau was capable of conveying without resorting to title cards (or their equivalent in talkies, the voice-over). This movie is also notable for its brilliant use of expressionism, and the first brilliant use of a tracking shot. In Murnau's The Last Laugh, silent movies metaphorically were given movement, and learned to run.

¿Sabías que…?

- TriviaThe first "dolly" (a device that allows a camera to move during a shot) was created for this film. According to Edgar G. Ulmer, who worked on the film, the idea to make the first dolly came from the desire to focus on Emil Jannings' face during the first shot of the movie, as he moved through the hotel. They obviously didn't know how to make a dolly technically, so they created the first one out of a baby's carriage. They then pulled the carriage on a sort of railway that was built in the studio.

- ErroresWhen the porter comes home with the stolen coat, the third button down (which fell off earlier) is still there until a close-up of him at the door.

- Versiones alternativasThere is an Italian edition of this film on DVD, re-edited in double version (1.33:1 and 1.78:1) with the contribution of film historian Riccardo Cusin. This version is also available for streaming on some platforms.

- ConexionesEdited into Alemania, año nueve cero (1991)

Selecciones populares

Inicia sesión para calificar y agrega a la lista de videos para obtener recomendaciones personalizadas

- How long is The Last Laugh?Con tecnología de Alexa

Detalles

Taquilla

- Total en EE. UU. y Canadá

- USD 94,812

- Tiempo de ejecución1 hora 28 minutos

- Color

- Mezcla de sonido

- Relación de aspecto

- 1.33 : 1

Contribuir a esta página

Sugiere una edición o agrega el contenido que falta

Principales brechas de datos

What is the Italian language plot outline for Der letzte Mann (1924)?

Responda