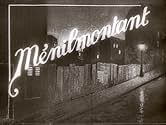

Ménilmontant

- 1926

- 38 Min.

IMDb-BEWERTUNG

7,8/10

2865

IHRE BEWERTUNG

Füge eine Handlung in deiner Sprache hinzuA couple is brutally murdered in the working-class district of Paris. Later on, the narrative follows the lives of their two daughters, both in love with a Parisian thug and leading them to ... Alles lesenA couple is brutally murdered in the working-class district of Paris. Later on, the narrative follows the lives of their two daughters, both in love with a Parisian thug and leading them to separate ways.A couple is brutally murdered in the working-class district of Paris. Later on, the narrative follows the lives of their two daughters, both in love with a Parisian thug and leading them to separate ways.

- Regie

- Drehbuch

- Hauptbesetzung

Empfohlene Bewertungen

Dmitri Kirsinov's Menilmontant is considered to be a landmark in the art of film-making. The story is sparse, melodramatic, and brief. The film is barely twenty minutes long. A young girl leaves home after a somewhat vague hatchet murder takes place. She spends time in the seedy streets of Menilmontant, a medieval suburb of Paris. She drifts through a relationship with her sister and man friend.

If you are looking for a strong story and character development, you may be missing the point. Kirsanov was trying to manipulate images in such a way as to get a reaction from his viewer. The bigger story is just a convention on which to hang his moody images. The axe murder with its choppy editing is a very early use of this sort of emotive technique. You are one moment under the flailing axe, interleaved with fast cuts of a howling victim. Later in the film the younger sister is the center of a blurry sensual reverie, her body and her grim surroundings in and out of focus. Silent film as art needs to be taken on its own terms. Kirsanov and other early filmmakers helped to define the way we view, and how we understand the film narrative. That understanding of how the film story works was established quite some time ago, which needs remembering by those of us not around in 1926. It was not foreordained that fast editing, double exposure and other techniques would come into their own. Someone had to prove the power of a restrained use of these formal ideas. Kirsanov did this in 1926.

If you are looking for a strong story and character development, you may be missing the point. Kirsanov was trying to manipulate images in such a way as to get a reaction from his viewer. The bigger story is just a convention on which to hang his moody images. The axe murder with its choppy editing is a very early use of this sort of emotive technique. You are one moment under the flailing axe, interleaved with fast cuts of a howling victim. Later in the film the younger sister is the center of a blurry sensual reverie, her body and her grim surroundings in and out of focus. Silent film as art needs to be taken on its own terms. Kirsanov and other early filmmakers helped to define the way we view, and how we understand the film narrative. That understanding of how the film story works was established quite some time ago, which needs remembering by those of us not around in 1926. It was not foreordained that fast editing, double exposure and other techniques would come into their own. Someone had to prove the power of a restrained use of these formal ideas. Kirsanov did this in 1926.

Watched Dimitri Kirsanoff's Ménilmontant last night. It's right out of the top drawer. Filmed in 1926 when the rubric for making a film was not yet set, the rules not there to be broken. You can sense the sheer vitality that the filmmaker is enabled with because of this. It feels like a Zola novel, a great portrait of urban life, and also a valuable document of the way Paris looked at the time. Kirsanoff is not weighed down by cinematic antecedents, there are no Hitchockian homages, no cinematic in-jokes, no nods to popular culture, no product placement. This makes the film alive with atmosphere, almost overflowing with it. Somehow Mr Kirsanoff places you in the film, makes you an insider to the innocence of childhood, the loneliness of the big city, the despair of poverty, the shock of betrayal.

His camera is like the Kino-Eye, and it looks at things the way real people look at them, making it the least phallic use of a camera that I have seen. The shots of the Seine, of the countryside, of Ménilmontant, and the roving, lingering, pace of the camera were quite literally breath-taking. There are no intertitles in this silent movie, and the plot is a little opaque, but really this is not taking the movie on its own terms, it is a masterpiece of camera-work and editing and provides the most atmosphere of any movie I have ever seen. It is ESSENTIAL to watch this movie at its 38 minute pace. I saw it on the double-disc Kino edition of Avant-garde: Experimental Cinema of the 1920s and 30s. This is the best value for money DVD on the market full stop.

Recently I watched Lang's The Testament of Dr Mabuse and became aware through his virtuosic use of sound, how taken for granted sound is in movies these days. Watching Ménilmontant makes you realise how taken for granted image is, most of modern cinema is simply about dubious storytelling to quote something I heard on TV, " it's a cultural wasteland filled with inappropriate metaphors and an unrealistic portrayal of life created by the liberal media elite". I recommend this movie to all lovers of cinema, it really is a movie that can make you once again enthuse about the moving image.

His camera is like the Kino-Eye, and it looks at things the way real people look at them, making it the least phallic use of a camera that I have seen. The shots of the Seine, of the countryside, of Ménilmontant, and the roving, lingering, pace of the camera were quite literally breath-taking. There are no intertitles in this silent movie, and the plot is a little opaque, but really this is not taking the movie on its own terms, it is a masterpiece of camera-work and editing and provides the most atmosphere of any movie I have ever seen. It is ESSENTIAL to watch this movie at its 38 minute pace. I saw it on the double-disc Kino edition of Avant-garde: Experimental Cinema of the 1920s and 30s. This is the best value for money DVD on the market full stop.

Recently I watched Lang's The Testament of Dr Mabuse and became aware through his virtuosic use of sound, how taken for granted sound is in movies these days. Watching Ménilmontant makes you realise how taken for granted image is, most of modern cinema is simply about dubious storytelling to quote something I heard on TV, " it's a cultural wasteland filled with inappropriate metaphors and an unrealistic portrayal of life created by the liberal media elite". I recommend this movie to all lovers of cinema, it really is a movie that can make you once again enthuse about the moving image.

10sandover

Poverty, disillusion, and yet grace graces the screen when Nadia Sibirskaya nods to the old man who offers her some food to chew. That scene, that means her social grace, brought me tears and elated me at once - miracles, oh yes, do and do happen and move.

One should note that the old man does not reciprocate, in fact does not look at her at all, and this marks Kirsanoff's extraordinary finesse: if there was some kind of "communication" between the two, THIS would be melodramatic; for I do not think this film is a melodrama, at least the way we have come to mean one. To deny that the story is something that could have "happened", is to deny the film's class and émigré conscience.

On the other hand I am not sure I would claim, as another reviewer did, that this is Zola-like; we would then be a bit far from "Menilmontant"'s drastic, dislocated lyricism.

Watch the cutting close-ups the two times Sibirskaya's eloquent face witnesses a violent scene: the camera, a bit dislocated each time, and unafraid to jump and shut transitive seconds.

Watch the scene where she strongly contemplates something and starts descending the steps to the river: there is a sense of menace and imminent loss, I am not sure I ever witnessed before in a film: this is film-making on the heights; as is the camera work which frames hesitant feet on the steps, and hushes astonishingly their turning round.

Watch the protagonist's face after she arguably loses her virginity: inscrutable and fascinating, not allowing us truly tell if the vision of her wandering in the woods is one of innocence lost or burgeoning sexuality. But there is, that is a visceral sense of feminine enjoyment, perhaps close to a Balthus painting mood.

At the end one is left with a sense of bifurcation: with sisters reconciled, we are left with a confusing and not redeeming crime. We don't know who or why exactly and if the girl involves herself out of vengeance, private reasons or what you will; that makes it all the more unsavory and artistically right.

Then the camera looks disjointedly up into the Parisian sky, and hands resume their work of artificial bouquets; yes, the film seems to suggest, this is all what one is left with, artificial bouquets and handiwork.

Two sisters, two deflorations, two crimes, twice the work of flowers: the work of the two Kirsanoffs genial, amazing sensibilities.

One should note that the old man does not reciprocate, in fact does not look at her at all, and this marks Kirsanoff's extraordinary finesse: if there was some kind of "communication" between the two, THIS would be melodramatic; for I do not think this film is a melodrama, at least the way we have come to mean one. To deny that the story is something that could have "happened", is to deny the film's class and émigré conscience.

On the other hand I am not sure I would claim, as another reviewer did, that this is Zola-like; we would then be a bit far from "Menilmontant"'s drastic, dislocated lyricism.

Watch the cutting close-ups the two times Sibirskaya's eloquent face witnesses a violent scene: the camera, a bit dislocated each time, and unafraid to jump and shut transitive seconds.

Watch the scene where she strongly contemplates something and starts descending the steps to the river: there is a sense of menace and imminent loss, I am not sure I ever witnessed before in a film: this is film-making on the heights; as is the camera work which frames hesitant feet on the steps, and hushes astonishingly their turning round.

Watch the protagonist's face after she arguably loses her virginity: inscrutable and fascinating, not allowing us truly tell if the vision of her wandering in the woods is one of innocence lost or burgeoning sexuality. But there is, that is a visceral sense of feminine enjoyment, perhaps close to a Balthus painting mood.

At the end one is left with a sense of bifurcation: with sisters reconciled, we are left with a confusing and not redeeming crime. We don't know who or why exactly and if the girl involves herself out of vengeance, private reasons or what you will; that makes it all the more unsavory and artistically right.

Then the camera looks disjointedly up into the Parisian sky, and hands resume their work of artificial bouquets; yes, the film seems to suggest, this is all what one is left with, artificial bouquets and handiwork.

Two sisters, two deflorations, two crimes, twice the work of flowers: the work of the two Kirsanoffs genial, amazing sensibilities.

I think "Menilmontant" is one of the great masterpieces of the silent era, and upon reading the comments posted, felt that it needed a little support. (If for nothing else than to encourage other people to seek it out, if not on video -- currently the only videos of this film have copied it at the wrong projection, thereby cranking up the film's speed and changing the running time from approximately 35 to 20 mins. -- than at a local museum or revival house; at least until someone puts out a definitive copy on video or DVD.)

Dimitri Kirsanoff's film centers on two young country girls who flee to the city after their parents are brutally murdered (we are given very few details as to who did this or why). The film's narrative is very sketchy, as there are no intertitles, and the two girls have similar features and are dressed similarly throughout most of the film. One of the girls, played by the wonderful Nadia Sibirskaia (Kirsanoff's wife), goes off with a man while her sister stays home in their tenement. When she returns home she soon has a baby, and her sister goes off (presumably as a prostitute) with the man. Sibirskaia presumably becomes homeless until she is ultimately reunited with her sister. The man they went away with earlier shows up again, only to be killed by a random criminal.

The film's slim and fragmented plot does nothing to convey the extraordinary and evocative world Kirsanoff creates through a barrage of disparate techniques lifted from German expressionism, Soviet montage, Hollywood melodrama, and the French avant-garde. The opening massacre is shown through a rapid Eisenstein-inspired montage; the compression of time and dreamlike waywardness of the girls' journey is presented through a series of lap dissolves; and the wintry, desolate atmosphere of Menilmontant (a poor, working class district on the eastern edge of Paris) is conveyed by an impressionistic use of documentary footage.

The film's most celebrated sequence occurs while Sibirskaia is wandering destitute on the streets of Paris (after contemplating drowning herself and her baby). Alone at night on a park bench, the young mother is cold and hungry, when an old man with a cane sits down on the bench next to her. The old man quietly shares some of his bread with her (never looking at her, he only lays the scraps and pieces on the bench separating them). The desperate girl tearfully accepts the food, and smiles, though the man barely looks her way. It's an extraordinarily sad and moving sequence that has echoes of Chaplin, but without that comedian's maudlin approach to sentiment. Sibirskaia's performance here is wonderfully nuanced and naturalistic -- there's very little of the histrionics usually associated with much silent film acting -- and she possesses a face that rivals Lillian Gish. The only comparable sequence I can think of is in Ozu's great 1935 silent film, An Inn in Tokyo.

In spite of its short length, this a film overflowing with riches. It ranks with the best films of any year.

Dimitri Kirsanoff's film centers on two young country girls who flee to the city after their parents are brutally murdered (we are given very few details as to who did this or why). The film's narrative is very sketchy, as there are no intertitles, and the two girls have similar features and are dressed similarly throughout most of the film. One of the girls, played by the wonderful Nadia Sibirskaia (Kirsanoff's wife), goes off with a man while her sister stays home in their tenement. When she returns home she soon has a baby, and her sister goes off (presumably as a prostitute) with the man. Sibirskaia presumably becomes homeless until she is ultimately reunited with her sister. The man they went away with earlier shows up again, only to be killed by a random criminal.

The film's slim and fragmented plot does nothing to convey the extraordinary and evocative world Kirsanoff creates through a barrage of disparate techniques lifted from German expressionism, Soviet montage, Hollywood melodrama, and the French avant-garde. The opening massacre is shown through a rapid Eisenstein-inspired montage; the compression of time and dreamlike waywardness of the girls' journey is presented through a series of lap dissolves; and the wintry, desolate atmosphere of Menilmontant (a poor, working class district on the eastern edge of Paris) is conveyed by an impressionistic use of documentary footage.

The film's most celebrated sequence occurs while Sibirskaia is wandering destitute on the streets of Paris (after contemplating drowning herself and her baby). Alone at night on a park bench, the young mother is cold and hungry, when an old man with a cane sits down on the bench next to her. The old man quietly shares some of his bread with her (never looking at her, he only lays the scraps and pieces on the bench separating them). The desperate girl tearfully accepts the food, and smiles, though the man barely looks her way. It's an extraordinarily sad and moving sequence that has echoes of Chaplin, but without that comedian's maudlin approach to sentiment. Sibirskaia's performance here is wonderfully nuanced and naturalistic -- there's very little of the histrionics usually associated with much silent film acting -- and she possesses a face that rivals Lillian Gish. The only comparable sequence I can think of is in Ozu's great 1935 silent film, An Inn in Tokyo.

In spite of its short length, this a film overflowing with riches. It ranks with the best films of any year.

There is an old German proverb that says that size doesn't matter ( well, size does count for this count having in mind the perimeter of his Teutonic heiresses

) and the saying rings true with "Ménilmontant" a medium-length silent film directed by Herr Dimitri Kirsanoff, and a striking, disturbing masterpiece.

Herr Kirsanoff's direction is astonishing in every aspect of the film, particularly in its technique. It's a mixture of drama, avant-garde, experimental film and hyper realism. The story depicted in the film ( the terrible life of two orphan sisters ) doesn't allow any concession to the audience; to watch "Ménilmontant" today still invokes amazement, distress and an infinite sadness.

From the very start of the film ( superb, striking and masterful editing by Herr Kirsanoff himself ) the director shows power and imagination and a strong control of film narrative ( there is no need of intertitles ). Kiransoff's use of imagery is thrilling and brilliant. Images emphasize a ruined happy childhood and the duality and dangers of a big city ( flashbacks, imaginative camera angles, dreamy and poetic shots ) not to mention the sorrowful life of the two orphans, an existence of loneliness, abandonment and despair that broke the heart of a heartless German aristocrat, especially the superb scene in which the younger sister ( touching Dame Nadia Sibirskaia ) ,alone and hungry on a bench park with her baby, accepts some bread from an old man, a moving and lyrical scene, that summarizes the spirit and achievement of this oeuvre.

"Ménilmontant" is a work of art, a striking experimental style in the service of a tragic and sad story, brilliantly and disturbingly balanced.

And now, if you'll allow me, I must temporarily take my leave because this German Count must become a little livelier.

Herr Graf Ferdinand Von Galitzien http://ferdinandvongalitzien.blogspot.com/

Herr Kirsanoff's direction is astonishing in every aspect of the film, particularly in its technique. It's a mixture of drama, avant-garde, experimental film and hyper realism. The story depicted in the film ( the terrible life of two orphan sisters ) doesn't allow any concession to the audience; to watch "Ménilmontant" today still invokes amazement, distress and an infinite sadness.

From the very start of the film ( superb, striking and masterful editing by Herr Kirsanoff himself ) the director shows power and imagination and a strong control of film narrative ( there is no need of intertitles ). Kiransoff's use of imagery is thrilling and brilliant. Images emphasize a ruined happy childhood and the duality and dangers of a big city ( flashbacks, imaginative camera angles, dreamy and poetic shots ) not to mention the sorrowful life of the two orphans, an existence of loneliness, abandonment and despair that broke the heart of a heartless German aristocrat, especially the superb scene in which the younger sister ( touching Dame Nadia Sibirskaia ) ,alone and hungry on a bench park with her baby, accepts some bread from an old man, a moving and lyrical scene, that summarizes the spirit and achievement of this oeuvre.

"Ménilmontant" is a work of art, a striking experimental style in the service of a tragic and sad story, brilliantly and disturbingly balanced.

And now, if you'll allow me, I must temporarily take my leave because this German Count must become a little livelier.

Herr Graf Ferdinand Von Galitzien http://ferdinandvongalitzien.blogspot.com/

Wusstest du schon

- WissenswertesPauline Kael said this was her favorite film of all time.

- Alternative VersionenThis film was published in Italy in an DVD anthology entitled "Avanguardia: Cinema sperimentale degli anni '20 e '30", distributed by DNA Srl. The film has been re-edited with the contribution of the film history scholar Riccardo Cusin . This version is also available in streaming on some platforms.

- VerbindungenFeatured in The language of the silent cinema 1895-1929 - Part II: 1926-1929 (1973)

Top-Auswahl

Melde dich zum Bewerten an und greife auf die Watchlist für personalisierte Empfehlungen zu.

Details

- Laufzeit38 Minuten

- Farbe

- Sound-Mix

- Seitenverhältnis

- 1.33 : 1

Zu dieser Seite beitragen

Bearbeitung vorschlagen oder fehlenden Inhalt hinzufügen