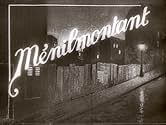

Ménilmontant

- 1926

- 38 Min.

IMDb-BEWERTUNG

7,8/10

2861

IHRE BEWERTUNG

Füge eine Handlung in deiner Sprache hinzuA couple is brutally murdered in the working-class district of Paris. Later on, the narrative follows the lives of their two daughters, both in love with a Parisian thug and leading them to ... Alles lesenA couple is brutally murdered in the working-class district of Paris. Later on, the narrative follows the lives of their two daughters, both in love with a Parisian thug and leading them to separate ways.A couple is brutally murdered in the working-class district of Paris. Later on, the narrative follows the lives of their two daughters, both in love with a Parisian thug and leading them to separate ways.

- Regie

- Drehbuch

- Hauptbesetzung

Empfohlene Bewertungen

After the violent and brutal death of their parents, two sisters leave to the big city to live. There, one of the sisters falls in love with a young man, but he is unfaithful and she is left having to deal with her own lost dreams and a baby without a job or a friend.

This is an interesting experimental film. It shows a lot more violence and sex than typically shown at the time, and yet it is very contemplative and serene in parts. However, as a subject of lost dreams, mostly it's very tragic. The image of interest here is the recurring motif of water. Water seems to provide all of the "insanity," including the boy seemingly coming from a spilt water barrel and a long montage of the woman contemplating something drastic as she looks out over the river.

It's powerfully affecting. It's strongest when hectic, during death or violence (beginning and end) or the sudden change from the serene quiet of the country to the speed and confusion of the city. It is a tragedy in every way, as lives are shattered in one way or another until a rather biting climax.

--PolarisDiB

This is an interesting experimental film. It shows a lot more violence and sex than typically shown at the time, and yet it is very contemplative and serene in parts. However, as a subject of lost dreams, mostly it's very tragic. The image of interest here is the recurring motif of water. Water seems to provide all of the "insanity," including the boy seemingly coming from a spilt water barrel and a long montage of the woman contemplating something drastic as she looks out over the river.

It's powerfully affecting. It's strongest when hectic, during death or violence (beginning and end) or the sudden change from the serene quiet of the country to the speed and confusion of the city. It is a tragedy in every way, as lives are shattered in one way or another until a rather biting climax.

--PolarisDiB

Menilmontant (1926) was, in the modest context of the alternative cinema circuit, a smash hit. It's great success allowed filmmaker Dimitri Kirsanov to go on making films, and also helped Jean Tedesco to stay in business as an exhibitor.

Like Kirsanov's first film, Menilmontant (again starring Kirsanoff's first wife, the beautiful Nadia Sibirskaia) tells a story without the use of inter-titles. It is often said that the filmmakers cinema is poetic, but one must add that in his second film he explored the poetics of violence and degradation.

The story begins and ends with two unrelated, but similarly filmed and edited murders. In each case, the grisly event does not grow organically out of the plot, but seems to surge out of a world welling with violent impulses.

Menilmontant uses practically all of the typical stylistic devices of cinematic impressionism, but it is hard to consider it as in any way representative of the movement. It's overwhelming, virtually unrelieved violence and despair seem to infect its own storytelling agency, upsetting what in other filmmakers' works would be clearly delineated relations of parts to the whole.

The film contains several bursts of rapid editing, for example, but they are not rhythmic in any simple, narratively justified way (in the manner of Abel Gance, for example); their meter is complicated and unsettling, worthy of an Igor Stravinsky. The film offers several notable examples of subjective camera work, but typically these become slightly unhinged, with no absolute certainty as to which character's experience in being rendered.

Menilmontant is, quite deliberately, a film in which the formal center cannot hold, because it is about a world in which this is also true. Although certainly not a Surrealist work, it shares with Surrealism no only a fascination with violence and sexuality, but also a display of forces and transcend, and question the boundaries of, individual human consciousness.

Kirsanov concluded his Menilmontant with a shot of impoverished and exploited young women fashioning artificial flowers in the poorest district of Paris, he provided us the most comprehensive image, aesthetic and social, of this form of cinema. Through a panoply of stylistic experiments and through glorious close-ups of the incomparably fragile face of Sibirskaia, Kirsanov thought he had shaped a harsh milieu into an exquisite flower. But a flower for whom? Menilmontant would become a major film on the cine-club and specialized cinema circuit, but never played to the people of the working class quatier that gave it its title. This was not Kirsanov's public anyway, for he came from the Russian aristocracy. In 1919, having fled the Revolution, he was reduced to playing his beloved cello in movie houses just to be able to eat. He must have been tempted to imagine himself and his music as an unappreciated flower in the crude milieu of mass art.

Seen this way, Menilmontant becomes a personal triumph of art over industry, of the icon of Sibirskaia over the brutal world of plot and spectacle that constitutes ordinary cinema. That triumph is signaled in the miracle of the film's narration, the first French film without titles, a tale told completely through the eloquence of its images. The dark alleys of the nineteenth arrondissment, the streetlights listening on the Seine, and the pathetic decor of shabby apartments are all redeemed by art. No silent film more clearly bewails the fate of art in our century, more obviously appeals to connoisseurs of the emotions roused by artificial flowers.

Like Kirsanov's first film, Menilmontant (again starring Kirsanoff's first wife, the beautiful Nadia Sibirskaia) tells a story without the use of inter-titles. It is often said that the filmmakers cinema is poetic, but one must add that in his second film he explored the poetics of violence and degradation.

The story begins and ends with two unrelated, but similarly filmed and edited murders. In each case, the grisly event does not grow organically out of the plot, but seems to surge out of a world welling with violent impulses.

Menilmontant uses practically all of the typical stylistic devices of cinematic impressionism, but it is hard to consider it as in any way representative of the movement. It's overwhelming, virtually unrelieved violence and despair seem to infect its own storytelling agency, upsetting what in other filmmakers' works would be clearly delineated relations of parts to the whole.

The film contains several bursts of rapid editing, for example, but they are not rhythmic in any simple, narratively justified way (in the manner of Abel Gance, for example); their meter is complicated and unsettling, worthy of an Igor Stravinsky. The film offers several notable examples of subjective camera work, but typically these become slightly unhinged, with no absolute certainty as to which character's experience in being rendered.

Menilmontant is, quite deliberately, a film in which the formal center cannot hold, because it is about a world in which this is also true. Although certainly not a Surrealist work, it shares with Surrealism no only a fascination with violence and sexuality, but also a display of forces and transcend, and question the boundaries of, individual human consciousness.

Kirsanov concluded his Menilmontant with a shot of impoverished and exploited young women fashioning artificial flowers in the poorest district of Paris, he provided us the most comprehensive image, aesthetic and social, of this form of cinema. Through a panoply of stylistic experiments and through glorious close-ups of the incomparably fragile face of Sibirskaia, Kirsanov thought he had shaped a harsh milieu into an exquisite flower. But a flower for whom? Menilmontant would become a major film on the cine-club and specialized cinema circuit, but never played to the people of the working class quatier that gave it its title. This was not Kirsanov's public anyway, for he came from the Russian aristocracy. In 1919, having fled the Revolution, he was reduced to playing his beloved cello in movie houses just to be able to eat. He must have been tempted to imagine himself and his music as an unappreciated flower in the crude milieu of mass art.

Seen this way, Menilmontant becomes a personal triumph of art over industry, of the icon of Sibirskaia over the brutal world of plot and spectacle that constitutes ordinary cinema. That triumph is signaled in the miracle of the film's narration, the first French film without titles, a tale told completely through the eloquence of its images. The dark alleys of the nineteenth arrondissment, the streetlights listening on the Seine, and the pathetic decor of shabby apartments are all redeemed by art. No silent film more clearly bewails the fate of art in our century, more obviously appeals to connoisseurs of the emotions roused by artificial flowers.

Watched Dimitri Kirsanoff's Ménilmontant last night. It's right out of the top drawer. Filmed in 1926 when the rubric for making a film was not yet set, the rules not there to be broken. You can sense the sheer vitality that the filmmaker is enabled with because of this. It feels like a Zola novel, a great portrait of urban life, and also a valuable document of the way Paris looked at the time. Kirsanoff is not weighed down by cinematic antecedents, there are no Hitchockian homages, no cinematic in-jokes, no nods to popular culture, no product placement. This makes the film alive with atmosphere, almost overflowing with it. Somehow Mr Kirsanoff places you in the film, makes you an insider to the innocence of childhood, the loneliness of the big city, the despair of poverty, the shock of betrayal.

His camera is like the Kino-Eye, and it looks at things the way real people look at them, making it the least phallic use of a camera that I have seen. The shots of the Seine, of the countryside, of Ménilmontant, and the roving, lingering, pace of the camera were quite literally breath-taking. There are no intertitles in this silent movie, and the plot is a little opaque, but really this is not taking the movie on its own terms, it is a masterpiece of camera-work and editing and provides the most atmosphere of any movie I have ever seen. It is ESSENTIAL to watch this movie at its 38 minute pace. I saw it on the double-disc Kino edition of Avant-garde: Experimental Cinema of the 1920s and 30s. This is the best value for money DVD on the market full stop.

Recently I watched Lang's The Testament of Dr Mabuse and became aware through his virtuosic use of sound, how taken for granted sound is in movies these days. Watching Ménilmontant makes you realise how taken for granted image is, most of modern cinema is simply about dubious storytelling to quote something I heard on TV, " it's a cultural wasteland filled with inappropriate metaphors and an unrealistic portrayal of life created by the liberal media elite". I recommend this movie to all lovers of cinema, it really is a movie that can make you once again enthuse about the moving image.

His camera is like the Kino-Eye, and it looks at things the way real people look at them, making it the least phallic use of a camera that I have seen. The shots of the Seine, of the countryside, of Ménilmontant, and the roving, lingering, pace of the camera were quite literally breath-taking. There are no intertitles in this silent movie, and the plot is a little opaque, but really this is not taking the movie on its own terms, it is a masterpiece of camera-work and editing and provides the most atmosphere of any movie I have ever seen. It is ESSENTIAL to watch this movie at its 38 minute pace. I saw it on the double-disc Kino edition of Avant-garde: Experimental Cinema of the 1920s and 30s. This is the best value for money DVD on the market full stop.

Recently I watched Lang's The Testament of Dr Mabuse and became aware through his virtuosic use of sound, how taken for granted sound is in movies these days. Watching Ménilmontant makes you realise how taken for granted image is, most of modern cinema is simply about dubious storytelling to quote something I heard on TV, " it's a cultural wasteland filled with inappropriate metaphors and an unrealistic portrayal of life created by the liberal media elite". I recommend this movie to all lovers of cinema, it really is a movie that can make you once again enthuse about the moving image.

I think "Menilmontant" is one of the great masterpieces of the silent era, and upon reading the comments posted, felt that it needed a little support. (If for nothing else than to encourage other people to seek it out, if not on video -- currently the only videos of this film have copied it at the wrong projection, thereby cranking up the film's speed and changing the running time from approximately 35 to 20 mins. -- than at a local museum or revival house; at least until someone puts out a definitive copy on video or DVD.)

Dimitri Kirsanoff's film centers on two young country girls who flee to the city after their parents are brutally murdered (we are given very few details as to who did this or why). The film's narrative is very sketchy, as there are no intertitles, and the two girls have similar features and are dressed similarly throughout most of the film. One of the girls, played by the wonderful Nadia Sibirskaia (Kirsanoff's wife), goes off with a man while her sister stays home in their tenement. When she returns home she soon has a baby, and her sister goes off (presumably as a prostitute) with the man. Sibirskaia presumably becomes homeless until she is ultimately reunited with her sister. The man they went away with earlier shows up again, only to be killed by a random criminal.

The film's slim and fragmented plot does nothing to convey the extraordinary and evocative world Kirsanoff creates through a barrage of disparate techniques lifted from German expressionism, Soviet montage, Hollywood melodrama, and the French avant-garde. The opening massacre is shown through a rapid Eisenstein-inspired montage; the compression of time and dreamlike waywardness of the girls' journey is presented through a series of lap dissolves; and the wintry, desolate atmosphere of Menilmontant (a poor, working class district on the eastern edge of Paris) is conveyed by an impressionistic use of documentary footage.

The film's most celebrated sequence occurs while Sibirskaia is wandering destitute on the streets of Paris (after contemplating drowning herself and her baby). Alone at night on a park bench, the young mother is cold and hungry, when an old man with a cane sits down on the bench next to her. The old man quietly shares some of his bread with her (never looking at her, he only lays the scraps and pieces on the bench separating them). The desperate girl tearfully accepts the food, and smiles, though the man barely looks her way. It's an extraordinarily sad and moving sequence that has echoes of Chaplin, but without that comedian's maudlin approach to sentiment. Sibirskaia's performance here is wonderfully nuanced and naturalistic -- there's very little of the histrionics usually associated with much silent film acting -- and she possesses a face that rivals Lillian Gish. The only comparable sequence I can think of is in Ozu's great 1935 silent film, An Inn in Tokyo.

In spite of its short length, this a film overflowing with riches. It ranks with the best films of any year.

Dimitri Kirsanoff's film centers on two young country girls who flee to the city after their parents are brutally murdered (we are given very few details as to who did this or why). The film's narrative is very sketchy, as there are no intertitles, and the two girls have similar features and are dressed similarly throughout most of the film. One of the girls, played by the wonderful Nadia Sibirskaia (Kirsanoff's wife), goes off with a man while her sister stays home in their tenement. When she returns home she soon has a baby, and her sister goes off (presumably as a prostitute) with the man. Sibirskaia presumably becomes homeless until she is ultimately reunited with her sister. The man they went away with earlier shows up again, only to be killed by a random criminal.

The film's slim and fragmented plot does nothing to convey the extraordinary and evocative world Kirsanoff creates through a barrage of disparate techniques lifted from German expressionism, Soviet montage, Hollywood melodrama, and the French avant-garde. The opening massacre is shown through a rapid Eisenstein-inspired montage; the compression of time and dreamlike waywardness of the girls' journey is presented through a series of lap dissolves; and the wintry, desolate atmosphere of Menilmontant (a poor, working class district on the eastern edge of Paris) is conveyed by an impressionistic use of documentary footage.

The film's most celebrated sequence occurs while Sibirskaia is wandering destitute on the streets of Paris (after contemplating drowning herself and her baby). Alone at night on a park bench, the young mother is cold and hungry, when an old man with a cane sits down on the bench next to her. The old man quietly shares some of his bread with her (never looking at her, he only lays the scraps and pieces on the bench separating them). The desperate girl tearfully accepts the food, and smiles, though the man barely looks her way. It's an extraordinarily sad and moving sequence that has echoes of Chaplin, but without that comedian's maudlin approach to sentiment. Sibirskaia's performance here is wonderfully nuanced and naturalistic -- there's very little of the histrionics usually associated with much silent film acting -- and she possesses a face that rivals Lillian Gish. The only comparable sequence I can think of is in Ozu's great 1935 silent film, An Inn in Tokyo.

In spite of its short length, this a film overflowing with riches. It ranks with the best films of any year.

This is one that no one can afford to miss in a lifetime of viewing, that is no one who's interested in the deepest workings of how things move. In my third viewing now, it may just be the pinnacle of the first 30 years. But before saying more, let's quickly clear the air from fixed perceptions so it can rise up in front of us vibrantly as what it is, all the more greater.

First to reclaim it from the museum of merely academic appreciation that covers, silents in particular, with the shroud of musky relic. Coming to us from so far back it may appear as the studied work of a venerable master - and yet it's the work of a 25 year old (filming started in '24) who shot it by himself with his girl around Paris, hand-held, and edited in camera.

The workings of fate or grande history that demand crowds and decor are pushed to the side, this is a youthful cinema ("indie" we would call it now) that beats with the heart of young people trying to fathom life in the complex city and I urge you see it as such. Kirsanov was an émigré new to Paris after all. Watch it as puzzling modern life that keeps you awake at nights, not as some scholar's symbolism.

Then to reclaim it from the clutches of "experimental" and "avant- garde", labels as though it were just about the tweaking of form, an exercise of trying to be ahead of time. There are many of those from the era, marvelous experiments in seeing, and Kirsanov was not just a wide-eyed country boy - he had articles published on "photogenie" before he made this and would know the radical tropes. But this enters beyond.

The best way I find myself able to describe it is this.

There's a story here that you can unfold in a way that it makes simple sense, melodrama about an orphaned girl lost in the big city. Melodrama since well before of course, offered us a certain facsimile of life where this clearly begat that, the disparity caused grief, the resolutions restored clarity. There's a heart breaking scene here on a bench worthy of Chaplin. She wanders with a baby cradled in her arms, trials and tribulations that innocence must go through.

Now this facsimile rippled and violently tossed about like curtains at an open window are shuffled by gusts of air, ellipsis, abstraction, rapid-fire montage, and all the other tools that Kirsanov would have known from being in Paris at the time of Epstein and others. So far so good. The film would have been great with just this mode, wholly visual, "experimental". The girl Nadia is lovely, the air dreamlike.

But there's something else he does, that is still in the process of being fathomed decades later by penetrative thinkers like Lynch. There are hidden machinations in the world of the film, illogical machinery at play, that turn at a level deeper than we can clearly fathom at any point. You should know here that Kirsanov had to cross a Europe collapsing by war and revolutions to reach Paris, he would have found out months after he left home that his father had been murdered on the street by communist thugs.

Suddenly there is the nagging sense of a presence that moves behind appearances, giving rise to mysteriously connected perturbations. A marvelous sequence shows one sister being seduced in a room (uncertain, but giving in), the other sister alone in their bed reading from a book as if daydreaming the whole dalliance.

And then the second sister knowingly letting herself be seduced, the first observing the scene from below as if she has splintered off into separate selves, one being seduced above, the other realizing in hallucinative daydream the mistake of giving herself to this boy.

This is marvelous. Impulses from an open window, and through the flimsy fabric of the curtains, the vague coming and going of people in a room, half-finished glimpses, but we begin to sense pattern here. Two girls, two murders, two seductions, but one calculated and wrong.

The most startling moment is the opening; a puzzling violence has stolen into this world, creating the story, rendered with haunting imagery of a struggle before a window. Now every account of the film I've read believes these are the parents of the girls and some madman, but this is not said anywhere. In the graveyard after, we see the father's grave with wreaths, a funeral that day, but none on the mother's, it looks abandoned. Maybe someone was caught where he shouldn't have been, calculated and wrong.

And this veiled and bubbling causality goes through everything to appear again in the finale; the first murder wasn't random, what says the second is? Maybe a holdup just so happened to visit him, maybe someone was paid off. The door is open, you go in where your body takes you.

Something to meditate upon

First to reclaim it from the museum of merely academic appreciation that covers, silents in particular, with the shroud of musky relic. Coming to us from so far back it may appear as the studied work of a venerable master - and yet it's the work of a 25 year old (filming started in '24) who shot it by himself with his girl around Paris, hand-held, and edited in camera.

The workings of fate or grande history that demand crowds and decor are pushed to the side, this is a youthful cinema ("indie" we would call it now) that beats with the heart of young people trying to fathom life in the complex city and I urge you see it as such. Kirsanov was an émigré new to Paris after all. Watch it as puzzling modern life that keeps you awake at nights, not as some scholar's symbolism.

Then to reclaim it from the clutches of "experimental" and "avant- garde", labels as though it were just about the tweaking of form, an exercise of trying to be ahead of time. There are many of those from the era, marvelous experiments in seeing, and Kirsanov was not just a wide-eyed country boy - he had articles published on "photogenie" before he made this and would know the radical tropes. But this enters beyond.

The best way I find myself able to describe it is this.

There's a story here that you can unfold in a way that it makes simple sense, melodrama about an orphaned girl lost in the big city. Melodrama since well before of course, offered us a certain facsimile of life where this clearly begat that, the disparity caused grief, the resolutions restored clarity. There's a heart breaking scene here on a bench worthy of Chaplin. She wanders with a baby cradled in her arms, trials and tribulations that innocence must go through.

Now this facsimile rippled and violently tossed about like curtains at an open window are shuffled by gusts of air, ellipsis, abstraction, rapid-fire montage, and all the other tools that Kirsanov would have known from being in Paris at the time of Epstein and others. So far so good. The film would have been great with just this mode, wholly visual, "experimental". The girl Nadia is lovely, the air dreamlike.

But there's something else he does, that is still in the process of being fathomed decades later by penetrative thinkers like Lynch. There are hidden machinations in the world of the film, illogical machinery at play, that turn at a level deeper than we can clearly fathom at any point. You should know here that Kirsanov had to cross a Europe collapsing by war and revolutions to reach Paris, he would have found out months after he left home that his father had been murdered on the street by communist thugs.

Suddenly there is the nagging sense of a presence that moves behind appearances, giving rise to mysteriously connected perturbations. A marvelous sequence shows one sister being seduced in a room (uncertain, but giving in), the other sister alone in their bed reading from a book as if daydreaming the whole dalliance.

And then the second sister knowingly letting herself be seduced, the first observing the scene from below as if she has splintered off into separate selves, one being seduced above, the other realizing in hallucinative daydream the mistake of giving herself to this boy.

This is marvelous. Impulses from an open window, and through the flimsy fabric of the curtains, the vague coming and going of people in a room, half-finished glimpses, but we begin to sense pattern here. Two girls, two murders, two seductions, but one calculated and wrong.

The most startling moment is the opening; a puzzling violence has stolen into this world, creating the story, rendered with haunting imagery of a struggle before a window. Now every account of the film I've read believes these are the parents of the girls and some madman, but this is not said anywhere. In the graveyard after, we see the father's grave with wreaths, a funeral that day, but none on the mother's, it looks abandoned. Maybe someone was caught where he shouldn't have been, calculated and wrong.

And this veiled and bubbling causality goes through everything to appear again in the finale; the first murder wasn't random, what says the second is? Maybe a holdup just so happened to visit him, maybe someone was paid off. The door is open, you go in where your body takes you.

Something to meditate upon

Wusstest du schon

- WissenswertesPauline Kael said this was her favorite film of all time.

- Alternative VersionenThis film was published in Italy in an DVD anthology entitled "Avanguardia: Cinema sperimentale degli anni '20 e '30", distributed by DNA Srl. The film has been re-edited with the contribution of the film history scholar Riccardo Cusin . This version is also available in streaming on some platforms.

- VerbindungenFeatured in The language of the silent cinema 1895-1929 - Part II: 1926-1929 (1973)

Top-Auswahl

Melde dich zum Bewerten an und greife auf die Watchlist für personalisierte Empfehlungen zu.

Details

- Laufzeit38 Minuten

- Farbe

- Sound-Mix

- Seitenverhältnis

- 1.33 : 1

Zu dieser Seite beitragen

Bearbeitung vorschlagen oder fehlenden Inhalt hinzufügen