Eine Sammlung professionell fotografierter Phänomene ohne eine konkrete Geschichte dahinter. Die Reihe thematisiert die Natur, die Menschheit und die Beziehung zwischen ihnen.Eine Sammlung professionell fotografierter Phänomene ohne eine konkrete Geschichte dahinter. Die Reihe thematisiert die Natur, die Menschheit und die Beziehung zwischen ihnen.Eine Sammlung professionell fotografierter Phänomene ohne eine konkrete Geschichte dahinter. Die Reihe thematisiert die Natur, die Menschheit und die Beziehung zwischen ihnen.

- Auszeichnungen

- 6 Gewinne & 1 Nominierung insgesamt

- Self - On TV

- (Archivfilmmaterial)

- (Nicht genannt)

- Self

- (Archivfilmmaterial)

- (Nicht genannt)

- Self - On TV

- (Archivfilmmaterial)

- (Nicht genannt)

- Self - On TV

- (Archivfilmmaterial)

- (Nicht genannt)

- Self - On TV

- (Archivfilmmaterial)

- (Nicht genannt)

- Self - On TV

- (Archivfilmmaterial)

- (Nicht genannt)

- Self - On TV

- (Archivfilmmaterial)

- (Nicht genannt)

- Self - On TV

- (Archivfilmmaterial)

- (Nicht genannt)

- Self - On TV

- (Archivfilmmaterial)

- (Nicht genannt)

- Self - On TV

- (Archivfilmmaterial)

- (Nicht genannt)

- Self - On TV

- (Archivfilmmaterial)

- (Nicht genannt)

- Self - On TV

- (Archivfilmmaterial)

- (Nicht genannt)

- Self - On TV

- (Archivfilmmaterial)

- (Nicht genannt)

- Self - On TV

- (Archivfilmmaterial)

- (Nicht genannt)

- Self - On TV

- (Archivfilmmaterial)

- (Nicht genannt)

Empfohlene Bewertungen

Filmed between 1977 and 1982, Reggio's film was noticed by directing great Francis Ford Coppola who eventually agreed to finance the project and give it chances for distribution. Minimalist composer Philip Glass was optioned to compose the score, and the result was, quite simply, astounding.

Koyaanisqatsi is a collection of familiar images presented through tinted lenses (figuratively speaking). The experimental nature of the project can be seen in the reduced and augmented speeds of images, the use of carefully manipulated edits, and the use of Glass's score to create ambience. There are times when the film exhibits an almost surreal quality more indicative of a twisted, futuristic, dystopian sci-fi epic than of our mundane world.

This is, however, what makes Koyaanisqatsi so successful. In presenting our world in a disquieting, unflattering light, the film forces us to ruminate on our place in the universe and the consequences of many of our actions. The film starts with serene, austere images of mountains, oceans, and forests, and the repetitiveness of Glass's score does not bore us nor call attention to itself, but simply washes over us, entrancing us and instilling a sense of tranquility.

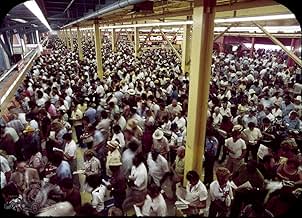

It is not long before the untainted images are replaced by nuclear power plants, highways, skyscrapers, rubble, fire and ash, and hoards of ant-like beings (humans, of course) scurrying through modern urbanity. Most times, humans are filmed at low-frame settings (making for faster speeds), and as a result, they seem frenzied, compulsively making their way through the cities in a manner that seems more conditioned than voluntary.

Glass's score responds by heightening its tension and adding a semi-brutal nature to its repetitiveness. It is somewhat aversive, but at the same time exhibits a humorous and mocking quality. By cramming together so many images of humans behaving more like lab rats than higher, thinking beings and increasing the satirical nature of the score, the film invites us to consider just how depersonalized, mechanized, and out-of-control many aspects of our life are.

The conclusion of the film contrasts against the blackly comic nature of the previous section by instilling a sense of mourning and warning. As such, there is undoubtedly a political and environmental component inherent in this film, but this is the aspect that is, in my mind, most often misunderstood. Many critics (mostly detractors) have interpreted Koyaanisqatsi as a call to action, an invective that demands that we atone for the rape-like pillaging the human race has thrusted upon the natural environment. Following from this, these critics claim that the film's message is that we would enjoy the planet more if we were not here at all, thus presenting a contradiction, since we would not be here to enjoy it.

In my own personal view, the flaw here resides in viewing the film as a tirade and a call to action. I find Koyaanisqatsi very clearly to be not a cry for reform, but a demand for awareness and meditation. There is an inevitability in the actions of human beings and their disregard for the care of their surroundings, and the wonderful thing about this film is that it forces you to experience the consequences and at least take notice of what each of us is contributing. It does not let you get away with indifference and nonchalance.

For me, however, the political component is less important than the stylistic component, which is one near and dear to my heart: the use of music to enhance the forcefulness of images. I acknowledge the fact that some will not be able to stand the repetitiveness of Philip Glass's score (and it is very repetitive at some points). But if one can consider the motive behind the repetition, the music ceases to be oppressive and becomes sublime and entrancing. The score adds impact to an already stunning array of unforgettable images, the details of which I will not go into, so that one may see the film with fresh eyes.

I saw Koyaanisqatsi for the first time at a performance in which the visuals were projected onto a giant screen with the soundtrack being supplied by Glass and his ensemble, who had come for a live performance. I had barely made it in time, since I struggled to find a parking space and was drenched from running in the rain. The moment the film started, however, all of the accumulated tensions in my body completely dissipated. It was not at all a cerebral experience, but an instinctive one in which I enjoyed the images and sounds for their own sakes.

When I left the performance, I was in a hypnotic daze, transfixed by what I had just seen. My initial impressions haven't changed to this day. I loved this film, and while the political and environmental concerns it addresses are important, what really makes this film for me is the instinctive, visceral power of its images and sounds. Koyaanisqatsi maroons its audience in an alternate version of reality that sheds disturbing light on our lives, and yet at the same time, it produces an unforgettable cinematic experience that is pervasively engrossing.

one of the great things about this film is that while the intrusion of man is initially presented as profane and abhorrent, ultimately there is found a symmetry to the human experience that is as organic as anything found in the `natural' world. i used to be tempted to perceive humans as the only species on the plant that didn't fit, that threw everything out of balance, as it were. but over time it has become apparent that even the blight of man on earth is a naturally occurring phenomenon. the evolution of life is the destruction of life. the circle is unbroken.

The best thing to do is to turn off all of the lights, pump up the sound and absorb yourself in the spectacle that unfolds on the screen. If you do this, you'll experience one of the most breathtaking, moving and exciting pieces of art ever. There are few films that reach these heights -- 2001: A Space Odyssey is the only one that instantly comes to mind.

Don't analyse it until it's finished. Talking through it will ruin it. I've found that the film works best on an emotional level so switch your brain off and just watch and listen. By the time it's finished, you'll feel like you've been on an exhausting and exhilarating journey that you'll want to take again not long afterwards.

The first half of Koyaanisqatsi is of a world full of beauty. The most memorable images for me are time-lapse photography of clouds and their shadows moving across the canyon-country landscapes of the desert southwest. Anyone who has spent hours gazing into a fire or watching waves at the beach will find the photography mesmerizing - one of few film experiences that convey natural beauty almost as well as the reality itself.

The second half of the film is an intentionally jarring contrast, starting with a depiction of mechanized destruction of the same beauty for human purposes, i.e. mining coal to produce electricity. The message soon becomes overwhelmingly plain: We are screwing the place up, and are immensely poorer for it. The sourpuss face of frustration and disgust on a woman vainly trying over and over again to light her cigarette with an empty lighter summed it up for me, although other viewers of any sensibility will find plenty of disturbing images from the second half of the film to identify with.

As my friends and I left the theater (sadly, this is one of those films that loses some of its impact on the small screen) one remarked "It's been done. They've made the movie I wanted to make". Some of the commentators here have basically said that, while Koyaanisqatsi is undoubtedly a very good film, they didn't like the message; one referred to people who would enjoy the movie as misanthropes.

While its opposite film, "My Dinner With Andre" was full of discussions about the unarguably wonderful meta-physical potential of sentient beings such as ourselves, and while I enjoyed it a great deal, the contrast between the two seemed to point out that we as a species really are rather full of ourselves at times. Whether one is inclined to agree, or just wishes to see a glimpse of another point of view, one cannot go wrong seeing Koyaanisqatsi. Like the Angel of Death silently pointing out to Ebaneezer Scrooge the error of his ways, this film's message IS unmistakable, and needs no words.

Wusstest du schon

- WissenswertesGodfrey Reggio was hooked on Philip Glass doing the music. He approached Glass through a mutual friend, and Glass replied, "I don't do film music." Reggio persisted, and finally the friend told Glass that the tenacious guy was not going to go away without at least an audience. Glass relented, though he still insisted he wasn't doing the music. Reggio put together a photo montage with Glass' music as the soundtrack, which he presented to Glass at a private screening in New York. Immediately following the screening, Glass agreed to score the film.

- PatzerThe two explosions at about 18 minutes into the film were shot with anamorphic lenses and not properly desqueezed for the film's 1.85:1 aspect ratio.

- Zitate

[last lines]

title card: Translation of the Hopi Prophecies sung in the film: "If we dig precious things from the land, we will invite disaster." - "Near the Day of Purification, there will be cobwebs spun back and forth in the sky." - "A container of ashes might one day be thrown from the sky, which could burn the land and boil the oceans."

- Crazy CreditsEnd credits go over mashed voice recordings in English ranging from call operator answers to television news.

- VerbindungenEdited into Hellwach (2006)

Top-Auswahl

Details

- Erscheinungsdatum

- Herkunftsland

- Offizieller Standort

- Sprachen

- Auch bekannt als

- Koyaanisqatsi

- Drehorte

- San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station, San Diego County, Kalifornien, USA(as seen from San Onofre State Beach)

- Produktionsfirmen

- Weitere beteiligte Unternehmen bei IMDbPro anzeigen

Box Office

- Bruttoertrag in den USA und Kanada

- 1.723.872 $

- Weltweiter Bruttoertrag

- 1.728.699 $

Zu dieser Seite beitragen