IMDb-BEWERTUNG

7,8/10

38.012

IHRE BEWERTUNG

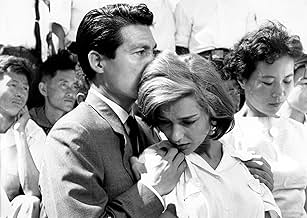

Eine französische Schauspielerin, die in Hiroshima einen Antikriegsfilm dreht, hat eine Affäre mit einem verheirateten japanischen Architekten, da sie ihre unterschiedlichen Ansichten über d... Alles lesenEine französische Schauspielerin, die in Hiroshima einen Antikriegsfilm dreht, hat eine Affäre mit einem verheirateten japanischen Architekten, da sie ihre unterschiedlichen Ansichten über den Krieg teilenEine französische Schauspielerin, die in Hiroshima einen Antikriegsfilm dreht, hat eine Affäre mit einem verheirateten japanischen Architekten, da sie ihre unterschiedlichen Ansichten über den Krieg teilen

- Für 1 Oscar nominiert

- 7 Gewinne & 7 Nominierungen insgesamt

Emmanuelle Riva

- Elle

- (as Emmanuele Riva)

Moira Lister

- (Dubbed Emmanuelle Riva)

- (Nicht genannt)

Empfohlene Bewertungen

Memory has persistently troubled filmmakers, this facet of consciousness by which the past overwrites the present. Where do these images come from, at what behest? More importantly, by invoking memory, how can we hope to communicate to others this past experience, which only perhaps existed once?

The woman says she saw Hiroshima, the charred asphalt and scorched metal, the matted hair coming out in tufts. We may have seen the same anonymous images of disaster, elsewhere, and think we saw. We see other people like her, like ourselves as mere spectators of a film, walk around the a-bomb museum in Hiroshima among the relics of disaster, lost in thought, impotent to reconstruct the experience from these glassed remnants of it. One of the great metaphors of memory, this museum that houses and presents fragmentary what used to be and how the spectators merely move inside it—internal observers of images.

The woman says she saw Hiroshima, but we know she didn't really experience. We know by the same images we may have seen, and which we see again in the film. We know this from our own private efforts to relive time gone. We see the objects and sounds but not having walked among them, we only know them vicariously. Can we ever get to know through cinema for that matter?

The great contribution of Resnais to cinema is firstly this, the realization that this medium is inherently equipped to inherit the problem of memory—just what is this illusory space. Inherently equipped in the same breath to fail to recapture the world as it was, like memory. Where Godard would be in thirty years, Resnais—and his friend Chris Marker—already was with his debut. He gives us here a more poignant, intelligent disclaimer of the artificiality of cinema than Godard ever did. The woman is of course an actress starring in a film—about peace we find out.

But Hiroshima is not the simple ploy of a trickster, it enters beyond.

We see in Hiroshima how the past forms that make up life as we have known it, and in which the self was forged, come into play. How these things, a past love or suffering thought to matter at the time, are only small by the distance of time. That we weren't shattered by them.

And we see how, having been, these forms will vanish again. How this present love and perhaps the suffering that will follow it, thought to matter now, will also come to pass and be forgotten. How we will perhaps try to recount these events at a future time, our reconstructions faced with the same impotence to make ourselves known or know in turn.

All that remains then, having walked the city in an effort to shape again from memory, is this moment, perhaps shared by two people on a bed. These walks taken together. Perhaps a story to tell or a film about it.

Something to meditate upon.

The woman says she saw Hiroshima, the charred asphalt and scorched metal, the matted hair coming out in tufts. We may have seen the same anonymous images of disaster, elsewhere, and think we saw. We see other people like her, like ourselves as mere spectators of a film, walk around the a-bomb museum in Hiroshima among the relics of disaster, lost in thought, impotent to reconstruct the experience from these glassed remnants of it. One of the great metaphors of memory, this museum that houses and presents fragmentary what used to be and how the spectators merely move inside it—internal observers of images.

The woman says she saw Hiroshima, but we know she didn't really experience. We know by the same images we may have seen, and which we see again in the film. We know this from our own private efforts to relive time gone. We see the objects and sounds but not having walked among them, we only know them vicariously. Can we ever get to know through cinema for that matter?

The great contribution of Resnais to cinema is firstly this, the realization that this medium is inherently equipped to inherit the problem of memory—just what is this illusory space. Inherently equipped in the same breath to fail to recapture the world as it was, like memory. Where Godard would be in thirty years, Resnais—and his friend Chris Marker—already was with his debut. He gives us here a more poignant, intelligent disclaimer of the artificiality of cinema than Godard ever did. The woman is of course an actress starring in a film—about peace we find out.

But Hiroshima is not the simple ploy of a trickster, it enters beyond.

We see in Hiroshima how the past forms that make up life as we have known it, and in which the self was forged, come into play. How these things, a past love or suffering thought to matter at the time, are only small by the distance of time. That we weren't shattered by them.

And we see how, having been, these forms will vanish again. How this present love and perhaps the suffering that will follow it, thought to matter now, will also come to pass and be forgotten. How we will perhaps try to recount these events at a future time, our reconstructions faced with the same impotence to make ourselves known or know in turn.

All that remains then, having walked the city in an effort to shape again from memory, is this moment, perhaps shared by two people on a bed. These walks taken together. Perhaps a story to tell or a film about it.

Something to meditate upon.

Hiroshima Mon Amour is brilliantly made and brilliantly acted, with a thoughtful, poetic script by the great French writer, Marguerite Duras. Its images are lyrical, disturbing, fascinating, and its anti-war message is profound and still frighteningly relevant. But in terms of strict entertainment...

Any film which begins with abstracted images of the entwined body parts of human lovers, slowly becoming encrusted with ash and (presumably) atomic fallout... and then spends an obscure 15 minutes arguing about the death and disfigurement of multitudes during the atomic bomb blast in Hiroshima, and the nature of memory and forgetfulness... well, you realize immediately that this movie isn't set up to go anyplace fun. Unless your idea of "fun" is witnessing someone else's graphic misery without the cleansing catharsis that accompanies a more conventional tragedy. Hey, some people enjoy that kind of thing! Not me, but to each his/her own.

Despite a structure which is famous for meandering through time, the film's narrative is fairly cogent and non-confusing, which is a plus. But the central illicit, inter-racial affair between a French actress and the Japanese architect whom she hooks up with during a film shoot in Hiroshima... It doesn't really make any sense. From the tiny acorn of a chance hookup, grows a mad-passionate love affair based almost entirely on memories dredged from the actress' past, which she disgorges to the architect, rather like a colorless Scheherezade, as she loses all rational connection to the present, conflating a youthful indiscretion with a deceased German soldier (and her subsequent descent into madness) with the non-happenings surrounding her current Japanese amour. German, Japanese... clearly, she can't tell these Axis races apart! I understand that the point of the film was not to create strict narrative coherence, but rather to delve into some kind of symbolic and psychic clash between this cold-yet-overwrought union of a French woman and her obsessed Japanese lover, and the horrors of War. But, despite some moments which are outright absurdist in effect, the overall tone of the film is grinding in its humorlessness. As I watched the characters fatalistically surrendering to their doom, all I could think was, "man, that Marguerite Duras must have been a drag to be romantically involved with." I mean, the Duras script, for all it's poetic symbolism and intellectual brilliance, etc etc, tells a story of people who are criminally passive and hopelessly clingy. Love seems to transform her characters into mere victims, of love, of war, of life, masochistically reveling in their own operatic suffering while doing virtually nothing. As the nameless SHE recalls her own suffering during her madness, scraping her fingertips off on the saltpeter-encrusted walls of her parent's cellar-prison, then receiving validation of existence by luxuriously sucking her own blood from her ravaged hands because otherwise she is utterly alone, all I could think was... Oh brother! This character is so badly damaged, how did she ever manage to get happily married before she embarked on this chance affair in Japan? The imagery is fabulous and intense, but are these really human beings that could have plausibly embarked on a journey together? One human being, actually, because the Japanese architect is little more than a handsome cipher of "love"... love, in this story, apparently meaning the obsession that arises from the act of physical copulation, an experience which is equated with destruction of the nuclear holocaust variety. So, Marguerite Duras clearly had issues surrounding her expression and experience of sexuality. And the film betrays little in the way of empathy, either, the characters are infused with an undercurrent of intense selfishness as they struggle to connect. HE is constantly delving into HER unhappy past even though it can give neither of them any pleasure or joy. The more HE delves, the more SHE becomes hopelessly entangled, and the more obsessed HE becomes... until the cold and bitter end.

At least in an opera, you get to revel in an outpouring of passion! In this bitter pill, everything is so cold and humorless... well, it really is difficult to understand why people wax enthusiastic over this film so much. There is much here to ADMIRE... but not much to love, in my opinion. Except intellectually, because the film is awash with symbolism and thought-provoking moments. As a viewing experience for the average intellectual, such as myself, however, I felt that once was enough. The time jumping and abstractions and other critically lauded elements of this movie have been done better and more entertainingly by others. Though this is the most emotionally powerful anti-nuclear statement I've ever seen, for which, as someone who had much of his family die in the Hiroshima nuclear blast, I am profoundly grateful.

Any film which begins with abstracted images of the entwined body parts of human lovers, slowly becoming encrusted with ash and (presumably) atomic fallout... and then spends an obscure 15 minutes arguing about the death and disfigurement of multitudes during the atomic bomb blast in Hiroshima, and the nature of memory and forgetfulness... well, you realize immediately that this movie isn't set up to go anyplace fun. Unless your idea of "fun" is witnessing someone else's graphic misery without the cleansing catharsis that accompanies a more conventional tragedy. Hey, some people enjoy that kind of thing! Not me, but to each his/her own.

Despite a structure which is famous for meandering through time, the film's narrative is fairly cogent and non-confusing, which is a plus. But the central illicit, inter-racial affair between a French actress and the Japanese architect whom she hooks up with during a film shoot in Hiroshima... It doesn't really make any sense. From the tiny acorn of a chance hookup, grows a mad-passionate love affair based almost entirely on memories dredged from the actress' past, which she disgorges to the architect, rather like a colorless Scheherezade, as she loses all rational connection to the present, conflating a youthful indiscretion with a deceased German soldier (and her subsequent descent into madness) with the non-happenings surrounding her current Japanese amour. German, Japanese... clearly, she can't tell these Axis races apart! I understand that the point of the film was not to create strict narrative coherence, but rather to delve into some kind of symbolic and psychic clash between this cold-yet-overwrought union of a French woman and her obsessed Japanese lover, and the horrors of War. But, despite some moments which are outright absurdist in effect, the overall tone of the film is grinding in its humorlessness. As I watched the characters fatalistically surrendering to their doom, all I could think was, "man, that Marguerite Duras must have been a drag to be romantically involved with." I mean, the Duras script, for all it's poetic symbolism and intellectual brilliance, etc etc, tells a story of people who are criminally passive and hopelessly clingy. Love seems to transform her characters into mere victims, of love, of war, of life, masochistically reveling in their own operatic suffering while doing virtually nothing. As the nameless SHE recalls her own suffering during her madness, scraping her fingertips off on the saltpeter-encrusted walls of her parent's cellar-prison, then receiving validation of existence by luxuriously sucking her own blood from her ravaged hands because otherwise she is utterly alone, all I could think was... Oh brother! This character is so badly damaged, how did she ever manage to get happily married before she embarked on this chance affair in Japan? The imagery is fabulous and intense, but are these really human beings that could have plausibly embarked on a journey together? One human being, actually, because the Japanese architect is little more than a handsome cipher of "love"... love, in this story, apparently meaning the obsession that arises from the act of physical copulation, an experience which is equated with destruction of the nuclear holocaust variety. So, Marguerite Duras clearly had issues surrounding her expression and experience of sexuality. And the film betrays little in the way of empathy, either, the characters are infused with an undercurrent of intense selfishness as they struggle to connect. HE is constantly delving into HER unhappy past even though it can give neither of them any pleasure or joy. The more HE delves, the more SHE becomes hopelessly entangled, and the more obsessed HE becomes... until the cold and bitter end.

At least in an opera, you get to revel in an outpouring of passion! In this bitter pill, everything is so cold and humorless... well, it really is difficult to understand why people wax enthusiastic over this film so much. There is much here to ADMIRE... but not much to love, in my opinion. Except intellectually, because the film is awash with symbolism and thought-provoking moments. As a viewing experience for the average intellectual, such as myself, however, I felt that once was enough. The time jumping and abstractions and other critically lauded elements of this movie have been done better and more entertainingly by others. Though this is the most emotionally powerful anti-nuclear statement I've ever seen, for which, as someone who had much of his family die in the Hiroshima nuclear blast, I am profoundly grateful.

10Hitchcoc

As a college freshman some 45 years ago, I saw this film in the student union They had a commitment to art films. I have to say that I do remember the stream of dialog between the two characters but little about the content. I knew he (the Japanese man) had lost his family on that August day. I recall her pulling inward as he becomes a bit demanding. Watching it with mature eyes and a fresh view of the world, I was brought back to these two traumatized characters and the war that changed them forever. It begins with a discussion of the Hiroshima museum which contains pictures and artifacts from that fateful day. He keeps telling her that she has not seen Hiroshima as they lay entwined in bed. His pain is more predictable. He lost his family that day while he was away. Hers takes a more melancholy road. As she opens up, she tells the story of a love affair with a German soldier whom she would meet in all manner of places. One day she found him dying, curled up on the ground. She sits with him until he dies. New of their trysts gets out and she is ostracized by her community, her hair cropped, beaten, and thrown in a cellar by her own family. She has not told this story to anyone, including her own husband, until now. While she feels somewhat liberated the pain is too deep. The Japanese man, also married, wants her to stay in Hiroshima. The movie is about the relationship going forward with such damaged people. She repeatedly tries to escape him, but he keeps resurfacing. The sad thing is that she desires him and so it's not as if she is being stalked. Resnais is a master with the camera, using black and white contrasting images, engaging flashbacks, close-ups. One really marvelous scene is where the young woman, who has been playing a small part in an anti-war film, is nearly trampled by protesters carrying signs. Hiroshima is constantly in her face. She has been hurt so badly by the war and is carrying a load of guilt. War carries with it a loss of innocence and pain beyond the obvious. This film really captures this.

"Hiroshima mon amour" (1959) is an extraordinary tale of two people, a French actress and a Japanese architect - a survivor of the blast at Hiroshima. They meet in Hiroshima fifteen years after August 6, 1945 and become lovers when she came there to working on an antiwar film. They both are hunted by the memories of war and what it does to human's lives and souls. Together they live their tragic past and uncertain present in a complex series of fantasies and nightmares, flashes of memory and persistence of it. The black-and-white images by Sasha Vierney and Mikio Takhashi, especially the opening montage of bodies intertwined are unforgettable and the power of subject matter is undeniable. My only problem is the film's Oscar nominated screenplay. It works perfectly for the most of the film but then it begins to move in circles making the last 20 minutes or so go on forever.

In my previous paper I said that À bout de souffle was an extremely complicated movie. Well, if we compare it to Resnais' Hiroshima, mon amour, it just seems to be a skilled aesthetic exercise. I think Resnais takes a further step in modern cinema intermingling influences from surrealism, modernism and the New Wave of French cinema: intimate topics, deep and changing characters, oneirism, unclear limits between reality and mind. His movie is a skilled masterpiece that really needs to be seen twice since its symbolism and action are extremely interwoven. Personally, I felt somewhat frustrated the first time I saw it. Indeed, I find that Resnais style in this film is too extreme in some ways. He twists action and mixes reality with memories in a way that makes the spectator lose his/her way once and again. On top of that, most usually action is extremely slow -quite the contrary of his colleague Godard- and takes are extremely long. Truffaut did shoot this kind of scenes, but his were also agile, attractive. Resnais is slow, exasperating, boring. We must think however that Hiroshima mon amour is a literary film, a long shot poem. The script is a literary work of art by Marguerite Duras. Indeed, dialogs are like lines in a poem, rhythmically broken, slow, as if they were declaimed instead of simply said. Resnais complements this poetry inserting strongly lyric scenes of the Japanese people and the city of Hiroshima and playing around with meaningful light, as we will see later. In my opinion, the main topic of this film is memories and how a forgotten dark past can shape our present and determine our future. Basically, the film tells the story of a woman who has gone through a painful experience in his youth: she loved a German soldier during the occupation of Nevers, her hometown in France. This caused despise from her family and her community. This is a story that she has not told ever before. But an affair with a Japanese man while she shoots a film in Hiroshima will wake up her memories. The Japanese man recalls her of her first love; let us remember for instance, when she remembers the German man hand when she sees the Japanese's -both of them have a similar hair style and color. At some point in the film, the Japanese will grow more interested in her life in Nevers -he thinks the key to win her love is there- and this will unleash harsh flashbacks in the French woman's memories. She has never told anyone: as she talks out, articulates her memories -while they are at the bar- she will experience very strong feelings. We cannot differentiate what she was feeling at the moment of the story or what she is feeling now, what is a fact and what is a memory. I find very interesting the scene in which they sit together at the bar: at some point she takes the Japanese man for her old love. She begins talking to him as if he was so. Her memories take her over and she talks what she feels, what she remembers. Light effects are magical: she is drowned in brightness while the Japanese man stays in the dark. She talks and talks and Resnais inserts the necessary flashback images. The Japanese at that moment acts as the voice of her own memory: he asks her once and again. Until a point when she suffers so dramatically that the Japanese man, the real one, slaps her in her face to wake her up. Now we find a sharp kind of awakening. While she talked everything was silent. Now, everything sound as what it is: a bar with people chattering and frogs in the dark stream outside. There are four main elements in the film that spin around the life of the French girl, whose name we do not know. Two cities: Nevers and Hiroshima. And two men: the German soldier and the Japanese man. There is a whole system of connections between these four elements in the center of which is her. Resnais uses the powerful image of Hiroshima, the sadness of the place and grief of the people to identify the sadness and grief of the Frecn girl at Nevers. On the other side, the Japanese man reminds her of the German soldier. There is not an exact parallelism between the two cities or the two men, but connections can be made. We must remember the images of the streets in Hiroshima and the images of Nevers -la Place de la République, the churches-, flowing at the same time. The beautiful but empty Loire, the dead fields of Hiroshima. Although we can see some parallelism between the two cities, Resnais ends up the film with a scene in which this relationship seems to be much stronger. 'Toi, ton nom est Hiroshima. - Et toi, ton nom est Nevers, en France'. However, I cannot figure out what is the exact relationship between the two cities: maybe a comparison between grief in the memory and actual grief in the present day. Whatever way it might be, Resnais leaves for us a cryptic, dark ending that we would have to figure out the best we can depending on the elements he has given us in the film.

Wusstest du schon

- WissenswertesThis film pioneered the use of jump cutting to and from a flashback, and of very brief flashbacks to suggest obtrusive memories.

- PatzerWhen Elle leaves the hotel to go the set, she is wearing a nurse's uniform with a headscarf and carrying a black handbag. When Lui meets her on the set, she is now wearing a skirt and blouse and still has the headscarf. When they leave the set, the headscarf is left behind. When they get to Lui's house, she now has a white jacket.

- VerbindungenEdited into Geschichte(n) des Kinos: Le contrôle de l'univers (1999)

Top-Auswahl

Melde dich zum Bewerten an und greife auf die Watchlist für personalisierte Empfehlungen zu.

- How long is Hiroshima Mon Amour?Powered by Alexa

Details

- Erscheinungsdatum

- Herkunftsländer

- Sprachen

- Auch bekannt als

- Hiroshima Mon Amour

- Drehorte

- Nevers, Nièvre, Frankreich(street scenes, river banks)

- Produktionsfirmen

- Weitere beteiligte Unternehmen bei IMDbPro anzeigen

Box Office

- Bruttoertrag in den USA und Kanada

- 96.439 $

- Eröffnungswochenende in den USA und in Kanada

- 18.494 $

- 19. Okt. 2014

- Weltweiter Bruttoertrag

- 139.947 $

- Laufzeit1 Stunde 30 Minuten

- Farbe

- Sound-Mix

- Seitenverhältnis

- 1.37 : 1

Zu dieser Seite beitragen

Bearbeitung vorschlagen oder fehlenden Inhalt hinzufügen

Oberste Lücke

By what name was Hiroshima, mon amour (1959) officially released in India in English?

Antwort