La coquille et le clergyman

- 1928

- 40 Min.

IMDb-BEWERTUNG

7,0/10

2390

IHRE BEWERTUNG

Füge eine Handlung in deiner Sprache hinzuObsessed with a general's woman, a clergyman has strange visions of death and lust, struggling against his own eroticism.Obsessed with a general's woman, a clergyman has strange visions of death and lust, struggling against his own eroticism.Obsessed with a general's woman, a clergyman has strange visions of death and lust, struggling against his own eroticism.

- Regie

- Drehbuch

- Hauptbesetzung

Empfohlene Bewertungen

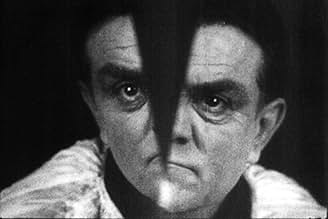

At first there seems to be some kind of science experiment. A potion is put from a vial into a pan by what looks to be a clergyman (?) and then a man in a General's uniform uses a sword to chop it down. The camera makes things look woozy, the frame and composition becoming warped and undone, like the feeling of going under or being drunk. We follow the Clergyman as he runs down a street (on his knees?) and then walks down a hall. There's also a woman, and the General is still there, but then... there's visions. He goes to another place mentally, perhaps, seeing a ship, water, waves, all sort of images that seem connected but disconnected at the same time. There's a room full of maids sweeping, then lined in formation. And then that 'Seashell' of the title - revealing (what else) boobs.

So much went into this film, the Seashell and the Clergyman, directed by Germain Dulac and written by one of the real-deal surrealists (and actor) Antonin Artuad, that I'm sure I could watch this five more times - and would want to - and get a different take on it each time. This preceded Un chien Andalou by a year, and yet I feel like these filmmakers and Bunuel/Dali were part of the same movement; whether Bunuel and Dali saw this film before they made their excursion is arguable, and I'd be curious to find out for sure (certainly the one moment where I went "Oh!" was when the clergyman reveals the seashell for the breasts - a similar shot happens in Andalou).

Yet it's impossible to make too many comparisons, because each surrealist goes about in their own way. This one has impressive, uncanny visual effects work for the time, mostly in ways of warping the frame - possibly by stretching the frame in post, or slow-motion in-camera. Then there's the simple act of one person being in a shot, and then the next someone popping up next to the actor through the jump-cut. Smoke is used to great effect at times, especially when violence occurs. Cinema tricks are plenty here, but what I took from the film is how it looks at the inner dream/mind-scape of such a person as the Clergyman. And perhaps this was Artaud's intention, maybe not (the British censors weren't sure what this was, but banned it anyway, possibly a gut reaction).

Why I read into it this way I'm not sure... actually, that's not totally true. It must be noted that this was directed not by a man (as Andalou) but a woman, and I think there's a different take on this because of that - a shot like the one with all the maids bustling about the room, doing their work almost like automatons, that has a woman's touch in a kind of satirical/absurd way. When I watch this film, I see a lot of sexualized imagery, a lot of repression, and it boiling over the surface. The version I watched on YouTube - with a great musical accompaniment that made it feel like a horror film in moments - had the air of an eerie land of nightmare and terror. The best surrealistic shorts has the stream-of-consciousness feel (think Deren or Bunuel or Man Ray), but this one especially has images that perhaps to make sense, in a Dream Logic sort of way, and if one were to follow the images as descriptions on paper, I'm sure it would read more like a poem.

It's a massively successful, deranged effort that can mean many things, but I have a feeling there's something strange about that Man of the Cloth...

So much went into this film, the Seashell and the Clergyman, directed by Germain Dulac and written by one of the real-deal surrealists (and actor) Antonin Artuad, that I'm sure I could watch this five more times - and would want to - and get a different take on it each time. This preceded Un chien Andalou by a year, and yet I feel like these filmmakers and Bunuel/Dali were part of the same movement; whether Bunuel and Dali saw this film before they made their excursion is arguable, and I'd be curious to find out for sure (certainly the one moment where I went "Oh!" was when the clergyman reveals the seashell for the breasts - a similar shot happens in Andalou).

Yet it's impossible to make too many comparisons, because each surrealist goes about in their own way. This one has impressive, uncanny visual effects work for the time, mostly in ways of warping the frame - possibly by stretching the frame in post, or slow-motion in-camera. Then there's the simple act of one person being in a shot, and then the next someone popping up next to the actor through the jump-cut. Smoke is used to great effect at times, especially when violence occurs. Cinema tricks are plenty here, but what I took from the film is how it looks at the inner dream/mind-scape of such a person as the Clergyman. And perhaps this was Artaud's intention, maybe not (the British censors weren't sure what this was, but banned it anyway, possibly a gut reaction).

Why I read into it this way I'm not sure... actually, that's not totally true. It must be noted that this was directed not by a man (as Andalou) but a woman, and I think there's a different take on this because of that - a shot like the one with all the maids bustling about the room, doing their work almost like automatons, that has a woman's touch in a kind of satirical/absurd way. When I watch this film, I see a lot of sexualized imagery, a lot of repression, and it boiling over the surface. The version I watched on YouTube - with a great musical accompaniment that made it feel like a horror film in moments - had the air of an eerie land of nightmare and terror. The best surrealistic shorts has the stream-of-consciousness feel (think Deren or Bunuel or Man Ray), but this one especially has images that perhaps to make sense, in a Dream Logic sort of way, and if one were to follow the images as descriptions on paper, I'm sure it would read more like a poem.

It's a massively successful, deranged effort that can mean many things, but I have a feeling there's something strange about that Man of the Cloth...

Germaine Dulac has created a monster here... Not in any kaiju sense, but by taking a surreal swipe at just about every element of the masculine-driven, religiously flawed environment of the world in the 1920s. The eponymous priest - Alex Allin harbours none too subtle desires about the mistress of "le général" (Lucien Bataille) - the beautiful Genica Athanasiou, and the next half hour illustrates some of the complex ramifications of this infatuation. Now I have watched this many times, each time thinking as I get older, that the penny may drop and that I shall discover a deeper meaning... Each time, I thoroughly enjoy the intimate, creative imagery and the truly characterful performances, but am still really none the wiser. I think that's what is enthralling about this short enigma of a feature. It stimulates questions, but doesn't answer any of them... Clearly, the director has an agenda, and a political point to make - but we are left to imagine a healthy amount of what this might be about. Is it erotic? Is it about frustration, excess...? I still don't really know....

Surrealism as an art form, emerging in Europe after World War One, was designed to be illogical, but appealing to the subconscious. In cinema, there's debate as to what was the first surrealistic film in history. But there's no doubt filmmaker Germaine Dulac's February 1928 "The Seashell and the Clergyman" could qualify as one of the first containing elements of surrealism in it.

The 40-minute film, about a member of the clergy who lusts after the wife of a general and attempts to suppress such thoughts, is a whirlwind of images disconnected from any plot. Members of the British Board of Film Censors were totally confused by the piece. They wrote Dulac's production was "so cryptic as to be almost meaningless. If there is a meaning, it is doubtless objectionable." The board banned the film in the United Kingdom. Even the book's author "The Seashell and the Clergyman" was based on, Antonin Artaud, a top avant-garde writer, frowned upon Dulac's version.

History, however, has proven more kind to "The Seashell and the Clergyman." Once other surrealistic films were released, most notably 1929's "Un Chien Andalou," whose makers claim was the first in that category, it was apparent that elements found in those films sprung from the images of Dulac's. The French feminist filmmaker, who earlier produced the highly-regarded 1922 "The Smiling Madam Beudet," now is recognized by film historians as the pioneer of surrealism. Her stated goal was to create a new "art of vision," one that through symbolic images reveal a series of metaphors. It was meant to stir the viewer's psyche. Dulac's objective in "The Seashell" was to create an entirely new visual language on the screen, addressing her audience members' unconsciousness. In that, many film critics agree, she succeeded.

The 40-minute film, about a member of the clergy who lusts after the wife of a general and attempts to suppress such thoughts, is a whirlwind of images disconnected from any plot. Members of the British Board of Film Censors were totally confused by the piece. They wrote Dulac's production was "so cryptic as to be almost meaningless. If there is a meaning, it is doubtless objectionable." The board banned the film in the United Kingdom. Even the book's author "The Seashell and the Clergyman" was based on, Antonin Artaud, a top avant-garde writer, frowned upon Dulac's version.

History, however, has proven more kind to "The Seashell and the Clergyman." Once other surrealistic films were released, most notably 1929's "Un Chien Andalou," whose makers claim was the first in that category, it was apparent that elements found in those films sprung from the images of Dulac's. The French feminist filmmaker, who earlier produced the highly-regarded 1922 "The Smiling Madam Beudet," now is recognized by film historians as the pioneer of surrealism. Her stated goal was to create a new "art of vision," one that through symbolic images reveal a series of metaphors. It was meant to stir the viewer's psyche. Dulac's objective in "The Seashell" was to create an entirely new visual language on the screen, addressing her audience members' unconsciousness. In that, many film critics agree, she succeeded.

It is maybe the most accurate depiction of dreams as I experience them that I have seen on film. It gets things right like the gradual construction of images when for example a building keeps changing shape (through dissolves between different buildings that were photographed similarly) before it finds its "final" shape (nothing is final in dreams), or an empty sea becomes a sea with a pier and a ship in it, or the other way around people, for example, dissolve into thin air while the surroundings stay the same. There is an inexplicable obsession with certain objects, but those objects aren't just part of some symbolic decoration without function, they are handled personally by the dreamer (the clergyman), almost as if objects that the dreamer doesn't touch also don't exist.

The dreamer goes through repetitive tasks like opening a door to walk trough a corridor to open a door to walk through a corridor to open...until new images are found to progress the dream. The clergyman is always driven. Even when it looks like he might be in charge of the moment his behavior feels compulsive, like filling one glass after another with a liquid and then letting the glass shatter on the floor again and again like on a loop. None of the other characters quite seem to have an own will either but the clergyman especially kind of seems like he is hypnotized throughout it.

There's also a lot of running here. Running away from something becomes a chasing after something. We see the person that the dreamer chases after but when we see the dreamer there is nobody in front of him. The person is still there and the chase continues, the person just isn't necessarily always visible, that the person's presence is felt is the real confirmation of the person being there.

We have our clergyman crawling towards an exit, in the next shot he crawls through the streets of Paris, then it cuts to some shots of the road obviously taken from a driving car, then a shot of him crawling around a corner, back to a shot of the road, then he runs around a corner, then another corner, and another,...

A rewatch confirmed that there is no film like it. Also that it makes no sense and that for me it doesn't say anything. Usually I wouldn't care all that much for such a film, yet I found it not just compelling but it's maybe also the first time that I'd call a film hypnotic. So here I am with this film feeling that for me it warrants not just a good score but full marks.

Despite the lack of sense and meaning and also the fact that you can never predict what shot you might see next, there is no confusion whatsoever in it. There are no scenes in the conventional sense, nor a story per se, just a constant flow of images with an intuitive progression that I always found very easy to follow. The definition of dream logic? I think so.

Like in a dream there are objects and actions that can be read as symbolic in retrospect in an attempt to make sense of it, but unlike so many other dream-like films nothing here feels symbolic. As far as I can tell it doesn't want you to figure out what it means or if it means anything at all. Nor do I think does it try to provoke, shock or amuse. According to the documentary about "The Seashell", called "Surimpressions", it is less concerned with the representation of a dream than with the "construction of its mental space-time, made of images of the world, in the world, transformed by the resources of cinema". Works for me.

The avant-garde "score for twelve instruments" of the 2005 Arte restoration (41 minutes in length) by a certain Iris ter Schiphorst, fits the film superbly. To quote NRC Handelsblad, 7 April 2005: "The music of the Dutch/German composer Iris ter Schiphorst related to the film quite naturally... a genuine unity of image and music. Sometimes it follows the associations very precisely, sometimes it takes its own path. Ter Schiphorst manages to elicit a very individual sound from the instruments: thin and unreal." "The Seashell" has a lot of varied camera tricks and optical effects but in most avant-garde films it feels like the trick came first, function follows form. Here, without anything making any logical sense, the trickery still feels like a means to an end, an end that is more than just delivering original and beautiful images. That the score isn't exactly comfortable and just as unpredictable as the images yet doesn't upstage them perhaps speaks for their strength.

The dreamer goes through repetitive tasks like opening a door to walk trough a corridor to open a door to walk through a corridor to open...until new images are found to progress the dream. The clergyman is always driven. Even when it looks like he might be in charge of the moment his behavior feels compulsive, like filling one glass after another with a liquid and then letting the glass shatter on the floor again and again like on a loop. None of the other characters quite seem to have an own will either but the clergyman especially kind of seems like he is hypnotized throughout it.

There's also a lot of running here. Running away from something becomes a chasing after something. We see the person that the dreamer chases after but when we see the dreamer there is nobody in front of him. The person is still there and the chase continues, the person just isn't necessarily always visible, that the person's presence is felt is the real confirmation of the person being there.

We have our clergyman crawling towards an exit, in the next shot he crawls through the streets of Paris, then it cuts to some shots of the road obviously taken from a driving car, then a shot of him crawling around a corner, back to a shot of the road, then he runs around a corner, then another corner, and another,...

A rewatch confirmed that there is no film like it. Also that it makes no sense and that for me it doesn't say anything. Usually I wouldn't care all that much for such a film, yet I found it not just compelling but it's maybe also the first time that I'd call a film hypnotic. So here I am with this film feeling that for me it warrants not just a good score but full marks.

Despite the lack of sense and meaning and also the fact that you can never predict what shot you might see next, there is no confusion whatsoever in it. There are no scenes in the conventional sense, nor a story per se, just a constant flow of images with an intuitive progression that I always found very easy to follow. The definition of dream logic? I think so.

Like in a dream there are objects and actions that can be read as symbolic in retrospect in an attempt to make sense of it, but unlike so many other dream-like films nothing here feels symbolic. As far as I can tell it doesn't want you to figure out what it means or if it means anything at all. Nor do I think does it try to provoke, shock or amuse. According to the documentary about "The Seashell", called "Surimpressions", it is less concerned with the representation of a dream than with the "construction of its mental space-time, made of images of the world, in the world, transformed by the resources of cinema". Works for me.

The avant-garde "score for twelve instruments" of the 2005 Arte restoration (41 minutes in length) by a certain Iris ter Schiphorst, fits the film superbly. To quote NRC Handelsblad, 7 April 2005: "The music of the Dutch/German composer Iris ter Schiphorst related to the film quite naturally... a genuine unity of image and music. Sometimes it follows the associations very precisely, sometimes it takes its own path. Ter Schiphorst manages to elicit a very individual sound from the instruments: thin and unreal." "The Seashell" has a lot of varied camera tricks and optical effects but in most avant-garde films it feels like the trick came first, function follows form. Here, without anything making any logical sense, the trickery still feels like a means to an end, an end that is more than just delivering original and beautiful images. That the score isn't exactly comfortable and just as unpredictable as the images yet doesn't upstage them perhaps speaks for their strength.

The predecessor of Un Chien Andalou and directed by the lone woman filmmaker of her time, La Coquille et le Clergyman is one of the most celebrated of French avant-garde movies of the '20s, partly because Antonin Artaud wrote the script, partly because the British censor of the time banned it with the legendary words 'If this film has a meaning, it is doubtless objectionable'. Artaud was reputedly unhappy with Dulac's realization of his scenario, and it's true that the story's anti-clericalism (a priest develops a lustful passion that plunges him into bizarre fantasies) is somewhat undermined by the director's determined visual lyricism. But the fragmentation of the narrative and the innovative imagery remain provocative, and the film is of course fascinating testimony to the currents of its time.

Wusstest du schon

- WissenswertesThe British Board of Film Censors banned this film in the UK in 1927, saying, "This film is so obscure as to have no apparent meaning. If there is a meaning, it is doubtless objectionable."

- VerbindungenEdited into Women Who Made the Movies (1992)

Top-Auswahl

Melde dich zum Bewerten an und greife auf die Watchlist für personalisierte Empfehlungen zu.

Details

- Erscheinungsdatum

- Herkunftsland

- Offizieller Standort

- Sprache

- Auch bekannt als

- Die Muschel und der Kleriker

- Drehorte

- Produktionsfirma

- Weitere beteiligte Unternehmen bei IMDbPro anzeigen

- Laufzeit40 Minuten

- Farbe

- Sound-Mix

- Seitenverhältnis

- 1.33 : 1

Zu dieser Seite beitragen

Bearbeitung vorschlagen oder fehlenden Inhalt hinzufügen

Oberste Lücke

By what name was La coquille et le clergyman (1928) officially released in Canada in English?

Antwort