IMDb-BEWERTUNG

7,3/10

5012

IHRE BEWERTUNG

Füge eine Handlung in deiner Sprache hinzuA man takes a job at an asylum with hopes of freeing his imprisoned wife.A man takes a job at an asylum with hopes of freeing his imprisoned wife.A man takes a job at an asylum with hopes of freeing his imprisoned wife.

Empfohlene Bewertungen

This is actually one of the titles of the film, a page out of order. It perfectly reflects the film itself, a narrative fractured, demented, cast in and out of a feverish mind, but ultimately incomplete to us, and the various misconceptions it has spawned in trying to evaluate as though it was the whole thing.

I was increasingly suspicious of this while watching, that I was basically confronted with an incomplete film and so a film impenetrable not wholly by design but only because the keys have been lost to us, or are not attached to the film we are watching and we have to apprehend elsewhere. Doing a little research afterwards only confirmed my doubts. So a little context:

-the film is not the tip of the iceberg of an advanced cinema whose main body is lamentably lost to us; it was saved exactly because it was an exception, a low-budget oddity the filmmaker himself re-discovered in his garden shed. The majority of silent Japanese cinema - whose final traces were eclipsed in the aftermath of WWII - were generic studio reworkings of popular material.

-it is not the product of an 'isolated cinematic environment free of influence', rather a studied attempt to recreate what the French avant-garde was pioneering at the time; so yes, the superimpositions, the haze of motions and details, the rapid-fire montage, all of them tools in the attempt to offer us a glimpse of the fractured, elusive reality of the mind, available tools at the time that Kinugasa knew from other films.

-so even though the idea of a janitor coming to work in a mental hospital may carry hues of Caligari, the film itself is from the line of what in France was called impressionism; the films of Epstein, L'Herbier, Gance.

-most importantly, even though the closest parable I can think of is Menilmontant, another French film from the same year that in place of story tried to paint with only images a state of mind from inside the mirror, that film was directly structured around images. It was intended to be seen as we have it. Watching Page it becomes increasingly obvious that a story deeply pertains to what we see; as was customary in Japan at the time, that story was meant to be narrated to the audience by a benshi, a narrator supplied by each theater. We may cobble together a view of that story from other sources, but the intended effect is lost to us.

-there is still the problem that in the version we have approximately one third of the film is missing. Most of it in the end from what I can tell, where the girl is supposed to marry her fiancé (which echoes and wonderfully annotates the scene where the janitor imagines himself reunited with his wife.

Oh, what we have of the film is more than fine, it's actually one of the most captivating visions of the mind in disarray from the time. But it was just not meant to be seen as merely a tone poem. The dreamy flow is clearly flowing somewhere. What we have instead is only what was salvaged from it but at the same time near complete enough, making barely enough sense to stand on its own, that we may be inclined to accept as the full vision.

We can still accept this itself as a fragment of madness and interpret from where our imagination takes us. That is fine, I encourage this.

Rumors have been circulating about a new restored version, hopefully one that - next to a better print - somehow includes the narration, preferably by a benshi, or intertitles at the very least. Until then, no rating from me.

I was increasingly suspicious of this while watching, that I was basically confronted with an incomplete film and so a film impenetrable not wholly by design but only because the keys have been lost to us, or are not attached to the film we are watching and we have to apprehend elsewhere. Doing a little research afterwards only confirmed my doubts. So a little context:

-the film is not the tip of the iceberg of an advanced cinema whose main body is lamentably lost to us; it was saved exactly because it was an exception, a low-budget oddity the filmmaker himself re-discovered in his garden shed. The majority of silent Japanese cinema - whose final traces were eclipsed in the aftermath of WWII - were generic studio reworkings of popular material.

-it is not the product of an 'isolated cinematic environment free of influence', rather a studied attempt to recreate what the French avant-garde was pioneering at the time; so yes, the superimpositions, the haze of motions and details, the rapid-fire montage, all of them tools in the attempt to offer us a glimpse of the fractured, elusive reality of the mind, available tools at the time that Kinugasa knew from other films.

-so even though the idea of a janitor coming to work in a mental hospital may carry hues of Caligari, the film itself is from the line of what in France was called impressionism; the films of Epstein, L'Herbier, Gance.

-most importantly, even though the closest parable I can think of is Menilmontant, another French film from the same year that in place of story tried to paint with only images a state of mind from inside the mirror, that film was directly structured around images. It was intended to be seen as we have it. Watching Page it becomes increasingly obvious that a story deeply pertains to what we see; as was customary in Japan at the time, that story was meant to be narrated to the audience by a benshi, a narrator supplied by each theater. We may cobble together a view of that story from other sources, but the intended effect is lost to us.

-there is still the problem that in the version we have approximately one third of the film is missing. Most of it in the end from what I can tell, where the girl is supposed to marry her fiancé (which echoes and wonderfully annotates the scene where the janitor imagines himself reunited with his wife.

Oh, what we have of the film is more than fine, it's actually one of the most captivating visions of the mind in disarray from the time. But it was just not meant to be seen as merely a tone poem. The dreamy flow is clearly flowing somewhere. What we have instead is only what was salvaged from it but at the same time near complete enough, making barely enough sense to stand on its own, that we may be inclined to accept as the full vision.

We can still accept this itself as a fragment of madness and interpret from where our imagination takes us. That is fine, I encourage this.

Rumors have been circulating about a new restored version, hopefully one that - next to a better print - somehow includes the narration, preferably by a benshi, or intertitles at the very least. Until then, no rating from me.

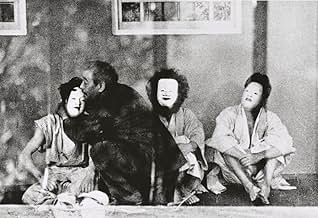

If you do not think you can take graphic scenes of mentally unstable people, this film is not for you.This story is about a man who takes a job at a local mental institution so he can be near his wife, who has gone mad. Throughout this long thought lost film you see clearly harrowing images of people at the institution. The soundtrack only adds to the foreboding. There are people lying catatonic and there is a dancer who doesn't stop dancing until she drops to the floor, exhausted. The film is 59 minutes long, I think it was originally longer but this was all that was found. There are no inter titles, its a silent film. In Japan, I am certain the benshi narrated the story in theaters, but your imagination has to follow this story. So, why a 7? It is daring, unflinching, brave and both ugly and not at the same time. As a point of reference only, Guy Maddin's work approaches this. Just know going in there is no happiness here. You won't soon forget this film. Best idea: Don't watch it before bedtime, it will stay with you.

...from director Teinosuke Kinugasa. A man (Masuo Inoue) works as a janitor at a mental asylum in order to be near his wife (Yoshie Nakagawa), who is a patient. The man's daughter (Ayako Iijima) is to be married soon, and questions of attendance are making things difficult for the man.

This meager narrative provides the framework for a lot of flash-cut editing, strobing visual tricks, and experimental cinema. This isn't interesting as a traditional story (at least, not the existing version, which is said to be missing nearly a third of its original footage), but rather in depicting madness and inner turmoil in a visual fashion. Even the usual silent film intertitles are absent, rendering the film a purely visual experience. The score that was used on the version I watched seemed like it was suited for a late 1960s acid party. The original release was said to have had a narrator and traditional Japanese music accompaniment. What I saw was still an interesting viewing, much of it closer to experimental films from the 1960s than what I'm used to seeing from the 1920s.

This meager narrative provides the framework for a lot of flash-cut editing, strobing visual tricks, and experimental cinema. This isn't interesting as a traditional story (at least, not the existing version, which is said to be missing nearly a third of its original footage), but rather in depicting madness and inner turmoil in a visual fashion. Even the usual silent film intertitles are absent, rendering the film a purely visual experience. The score that was used on the version I watched seemed like it was suited for a late 1960s acid party. The original release was said to have had a narrator and traditional Japanese music accompaniment. What I saw was still an interesting viewing, much of it closer to experimental films from the 1960s than what I'm used to seeing from the 1920s.

Kurutta ippêji (1926)

*** (out of 4)

Bizarre Japanese horror film has a man taking a janitor job at an asylum so that he can be closer to his wife who was committed after trying to kill their child. Had Luis Bunuel been bore in Japan and started making movies in 1926 then I'm guessing the final product would have came out looking like this thing. Lost for decades, it's easy to see why this film was never discovered but now that it's making its way around, it seems like this is destined to become something of a cult favorite to silent and horror fans. There's no straight story being told here, instead it's more avant-garde as we get all sorts of surreal images. We get the basic story but everything else is either told in flashback or through extra fast editing that helps build up the insanity of the lead character. Director Teinosuke Kinugasa really wants to get inside the mind of the insane and I think he does a pretty good job with it. At just 59-minutes the film moves at a pretty fast rate and a lot of this can be credited to the editing. I thought that the editing was the real star of the movie as it's done in such a fashion that you often see something but then you question what it was that you actually saw. You also have to try and keep up with what's going on and everything is happening so fast that you can see that the director was trying to use this to make the viewer feel what the characters were feeling being the asylum walls. There aren't any intertitles, which just adds to the visual image and the music score (done in the 70s) fits the film very well.

*** (out of 4)

Bizarre Japanese horror film has a man taking a janitor job at an asylum so that he can be closer to his wife who was committed after trying to kill their child. Had Luis Bunuel been bore in Japan and started making movies in 1926 then I'm guessing the final product would have came out looking like this thing. Lost for decades, it's easy to see why this film was never discovered but now that it's making its way around, it seems like this is destined to become something of a cult favorite to silent and horror fans. There's no straight story being told here, instead it's more avant-garde as we get all sorts of surreal images. We get the basic story but everything else is either told in flashback or through extra fast editing that helps build up the insanity of the lead character. Director Teinosuke Kinugasa really wants to get inside the mind of the insane and I think he does a pretty good job with it. At just 59-minutes the film moves at a pretty fast rate and a lot of this can be credited to the editing. I thought that the editing was the real star of the movie as it's done in such a fashion that you often see something but then you question what it was that you actually saw. You also have to try and keep up with what's going on and everything is happening so fast that you can see that the director was trying to use this to make the viewer feel what the characters were feeling being the asylum walls. There aren't any intertitles, which just adds to the visual image and the music score (done in the 70s) fits the film very well.

A Page of Madness is an expressionistic Japanese film that has not gotten the attention it deserves. I was introduced to the film through the fifteen part documentary series The Story of Film an Odyssey. Fortunately, a friend had dubbed the silent film off of Turner Classic Movies during one of its infrequent showings.

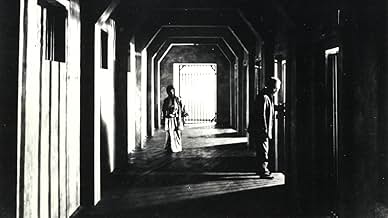

The clip in The Story of a Film an Odyssey looked like some mad movie genius had crossed the set designs from a German expressionist film with the fast edits of a classic Russian work. This clip was from the attention grabbing opening of A Page of Madness. A janitor wanders an insane asylum at night during a storm. The storm has a strange effect on the patients and, presumably, the attendant. The edits are fast, conveying mystery and terror like in a horror film. This sequence (and a sequence at the climax) is nothing short of brilliance.

From here the film turns to a narrative, although an oblique one. This clerk or janitor seems to have an unhealthy fixation on one of the female patients. . . and more of one for this patient's daughter. The janitor clearly knew this family before the mother was committed. IMDb says that the woman is the janitor's wife. I am not doubting this, but the film is not clear on this point. What is clear is that the janitor is suffering from a lack of love. This janitor is not the only one. One patient is compelled to dance suggestively and nearly starts a riot. By contrast, the doctors appear clinical and ineffectual. As the film goes along, the protagonist's mental state seems to wane.

Much about the plot is unclear. Many Japanese silent were narrated by a spokesman in the theater. This may have been the case with A Page of Madness; thus, some of the ambiguity would have been explained by the live narrator. I prefer to think the ambiguity was deliberate and never explained. The film has a wonderful sense of mystery to it. I don't want any more of an explanation. I (and probably most film fans) watch a lot of movies that are merely fair. These films are watchable, but they do not stay in one's memory. That is why A Page of Madness is so stunning. It kicks the door down and announces itself to the world. I feel less like a reviewer than a herald for a lost classic. Are you listening Criterion?

The clip in The Story of a Film an Odyssey looked like some mad movie genius had crossed the set designs from a German expressionist film with the fast edits of a classic Russian work. This clip was from the attention grabbing opening of A Page of Madness. A janitor wanders an insane asylum at night during a storm. The storm has a strange effect on the patients and, presumably, the attendant. The edits are fast, conveying mystery and terror like in a horror film. This sequence (and a sequence at the climax) is nothing short of brilliance.

From here the film turns to a narrative, although an oblique one. This clerk or janitor seems to have an unhealthy fixation on one of the female patients. . . and more of one for this patient's daughter. The janitor clearly knew this family before the mother was committed. IMDb says that the woman is the janitor's wife. I am not doubting this, but the film is not clear on this point. What is clear is that the janitor is suffering from a lack of love. This janitor is not the only one. One patient is compelled to dance suggestively and nearly starts a riot. By contrast, the doctors appear clinical and ineffectual. As the film goes along, the protagonist's mental state seems to wane.

Much about the plot is unclear. Many Japanese silent were narrated by a spokesman in the theater. This may have been the case with A Page of Madness; thus, some of the ambiguity would have been explained by the live narrator. I prefer to think the ambiguity was deliberate and never explained. The film has a wonderful sense of mystery to it. I don't want any more of an explanation. I (and probably most film fans) watch a lot of movies that are merely fair. These films are watchable, but they do not stay in one's memory. That is why A Page of Madness is so stunning. It kicks the door down and announces itself to the world. I feel less like a reviewer than a herald for a lost classic. Are you listening Criterion?

Wusstest du schon

- WissenswertesThis film was deemed lost for more than forty years, but it was rediscovered by its director, Teinosuke Kinugasa, in a rice cans in 1971.

- Alternative VersionenReissued in Japan in 1973 with musical score replacing original benshi.

- VerbindungenFeatured in The Story of Film: An Odyssey: The Golden Age of World Cinema (2011)

Top-Auswahl

Melde dich zum Bewerten an und greife auf die Watchlist für personalisierte Empfehlungen zu.

- How long is A Page of Madness?Powered by Alexa

Details

Box Office

- Budget

- 20.000 ¥ (geschätzt)

- Laufzeit1 Stunde 10 Minuten

- Farbe

- Sound-Mix

- Seitenverhältnis

- 1.33 : 1

Zu dieser Seite beitragen

Bearbeitung vorschlagen oder fehlenden Inhalt hinzufügen